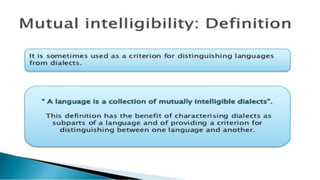

Mutual intelligibility is commonly used to distinguish between dialects and languages, but it has several problems. It is not objective as some speakers may understand a variety while others cannot. Additionally, there are examples of dialects within a continuum that blend into one another across borders, demonstrating that political borders do not define languages. There are also examples of distinct languages like Hindi and Urdu that are mutually intelligible in spoken form. Finally, some unintelligible varieties like Cantonese and Mandarin are still considered dialects of the same language by their speakers due to shared writing systems and culture. Overall, mutual intelligibility is not a reliable criterion when political, social and cultural identities influence language variations.