This document discusses peritonitis, including its anatomy, physiology, causes, classification, clinical presentation, diagnosis, and treatment. Some key points include:

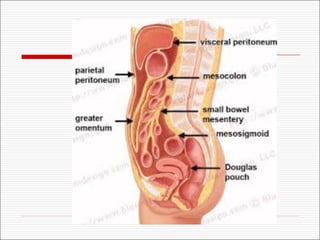

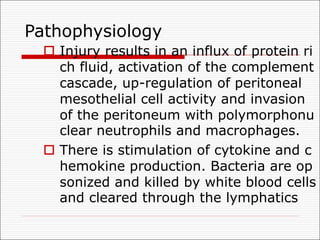

1. The peritoneum is a serous membrane that lines the abdominal cavity. Peritonitis is an inflammation of the peritoneum that can be caused by infections, injuries, or medical procedures.

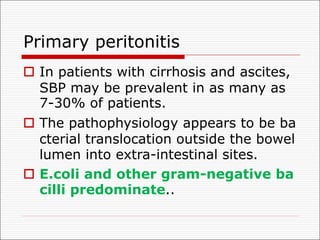

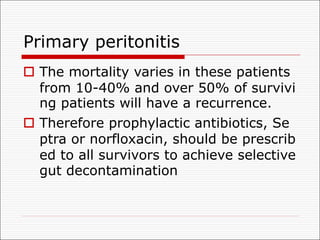

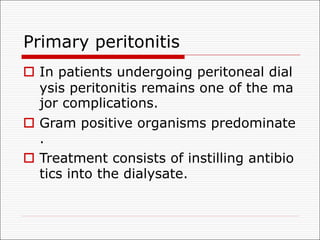

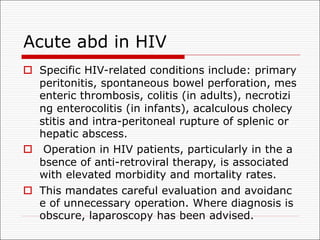

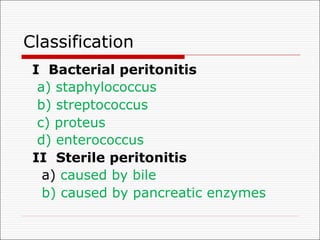

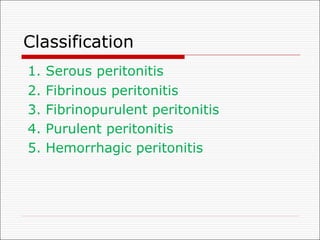

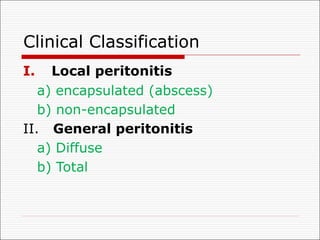

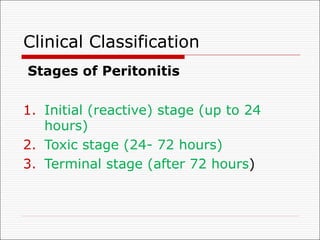

2. Peritonitis is classified as primary, secondary, or tertiary depending on the cause. The most common type encountered by surgeons is secondary peritonitis from a perforated organ.

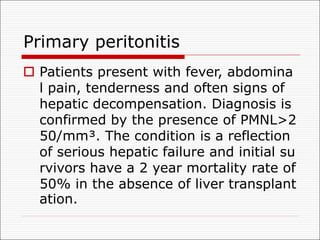

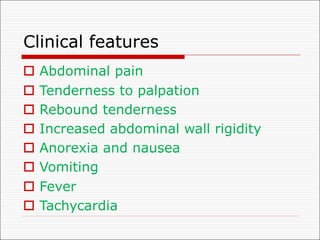

3. Clinical features include abdominal pain, tenderness, fever, and nausea/vomiting. Diagnosis involves physical exam, history, and imaging tests