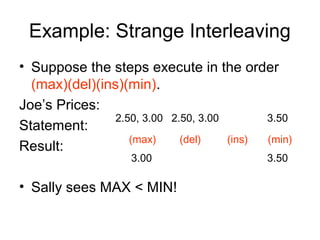

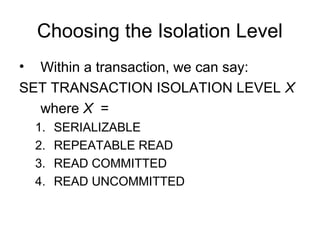

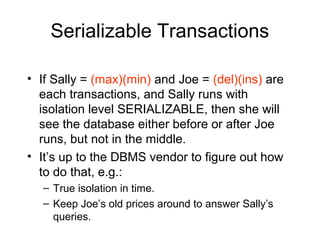

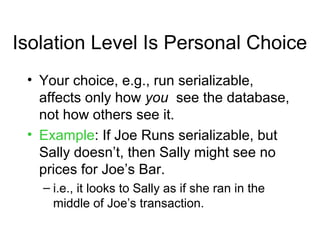

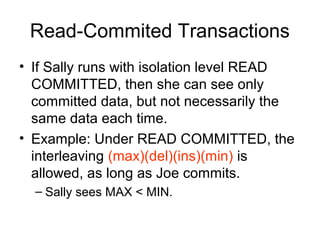

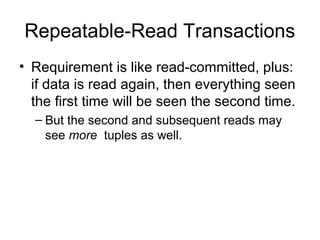

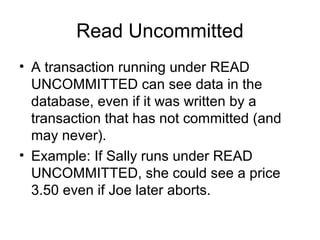

This document discusses transactions in SQL and database management systems. It explains that DBMSs use transactions to ensure atomicity, consistency, isolation, and durability when multiple users access and modify data simultaneously. SQL supports transactions through statements like COMMIT, ROLLBACK, and by setting the transaction isolation level. The isolation level determines how transactions interact with each other and see concurrent changes to the database.