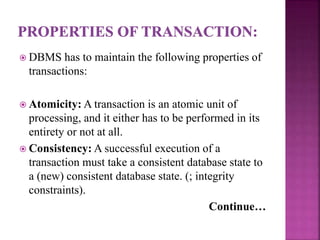

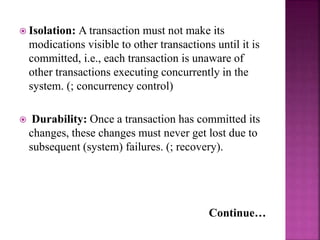

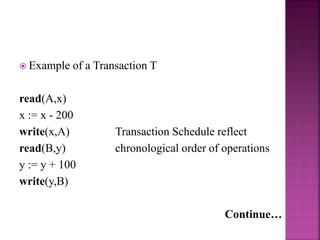

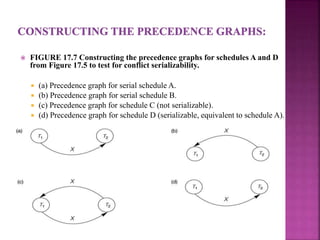

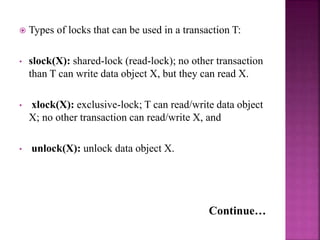

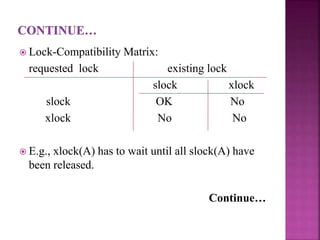

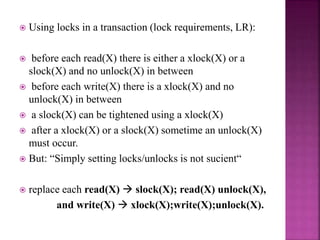

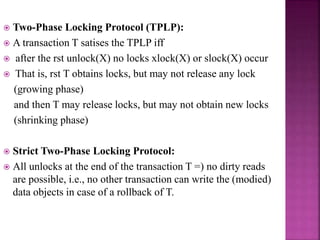

This document discusses transaction processing and concurrency control in database systems. It defines a transaction as a unit of program execution that accesses and possibly modifies data. It describes the key properties of transactions as atomicity, consistency, isolation, and durability. It discusses how concurrency control techniques like locking and two-phase locking protocols are used to ensure serializable execution of concurrent transactions.