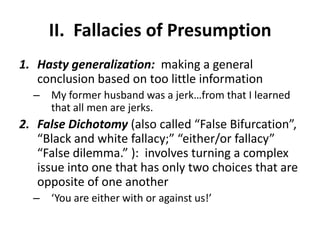

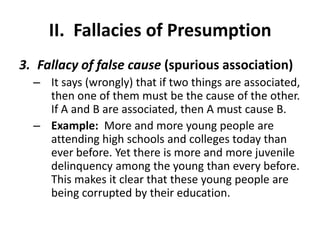

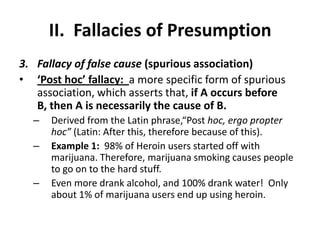

This document summarizes common fallacies that can occur in social research. It discusses the problem of contamination, fallacies of presumption like hasty generalization and false dichotomies, fallacies of the wrong level like ecological and reductionist fallacies, and non sequitur fallacies where the conclusion does not logically follow from the premises. Specific examples are provided for each type of fallacy.