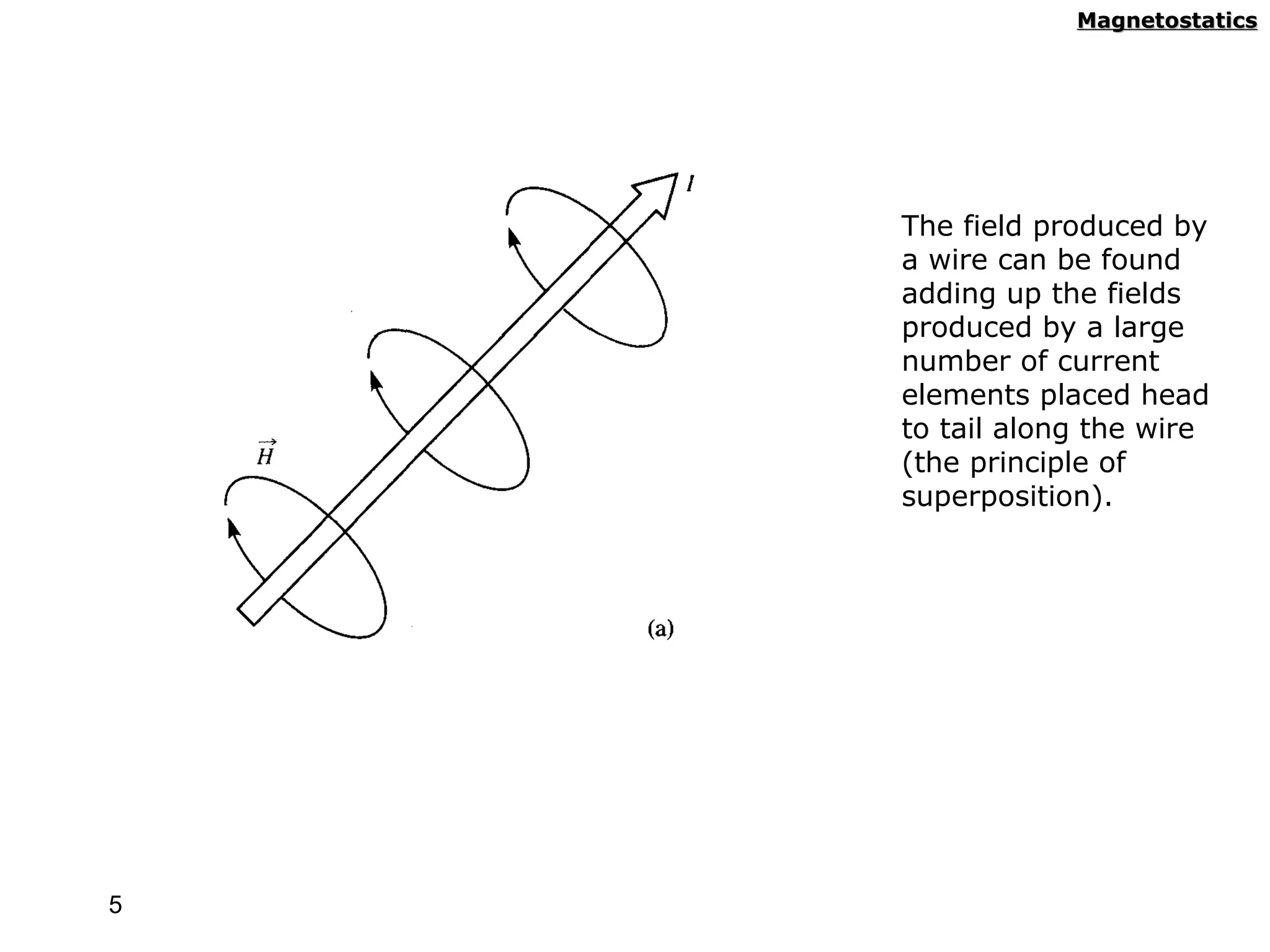

1) Magnetostatic fields are produced when charges move with constant velocity, originating from currents like those in wires.

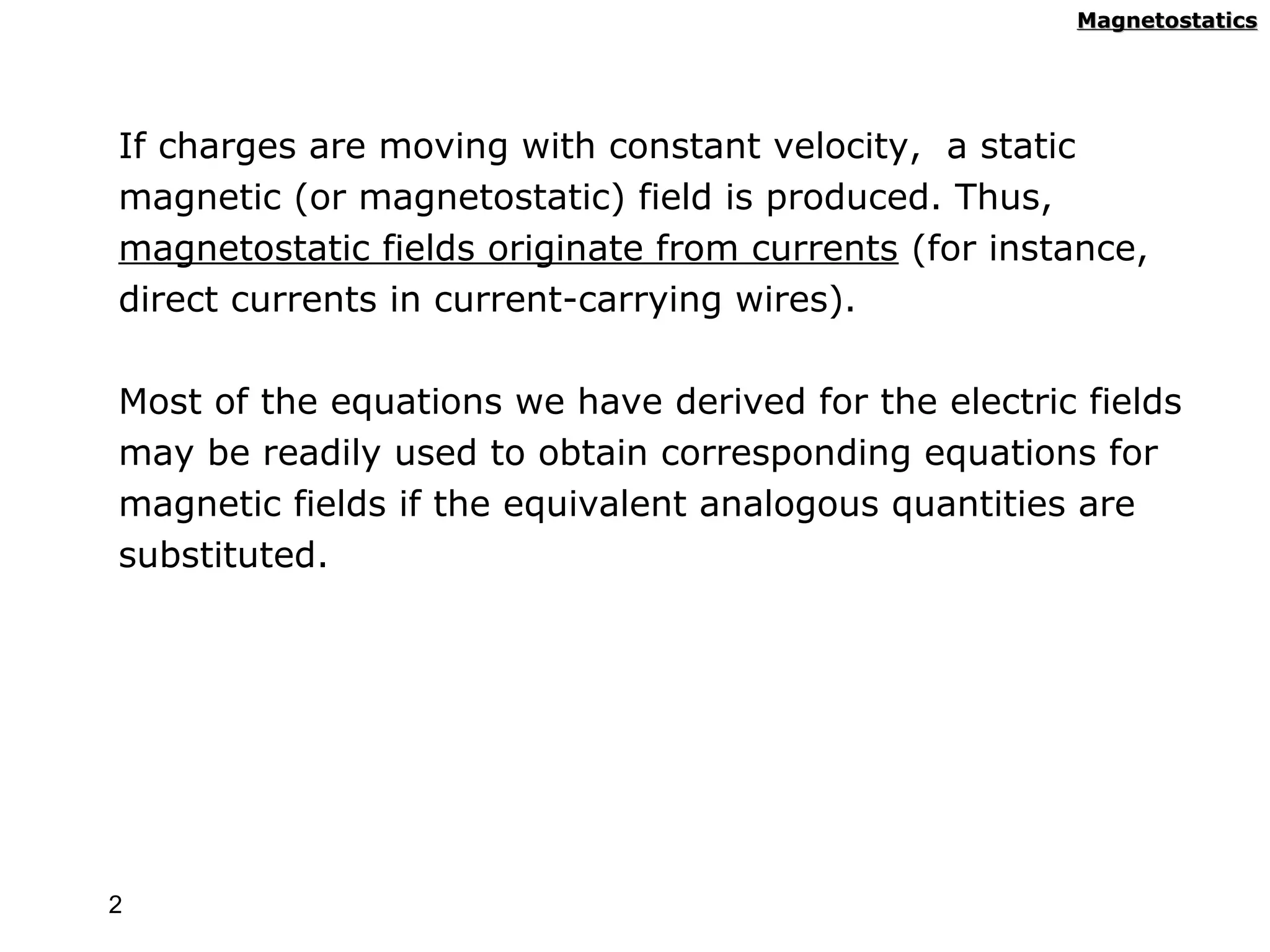

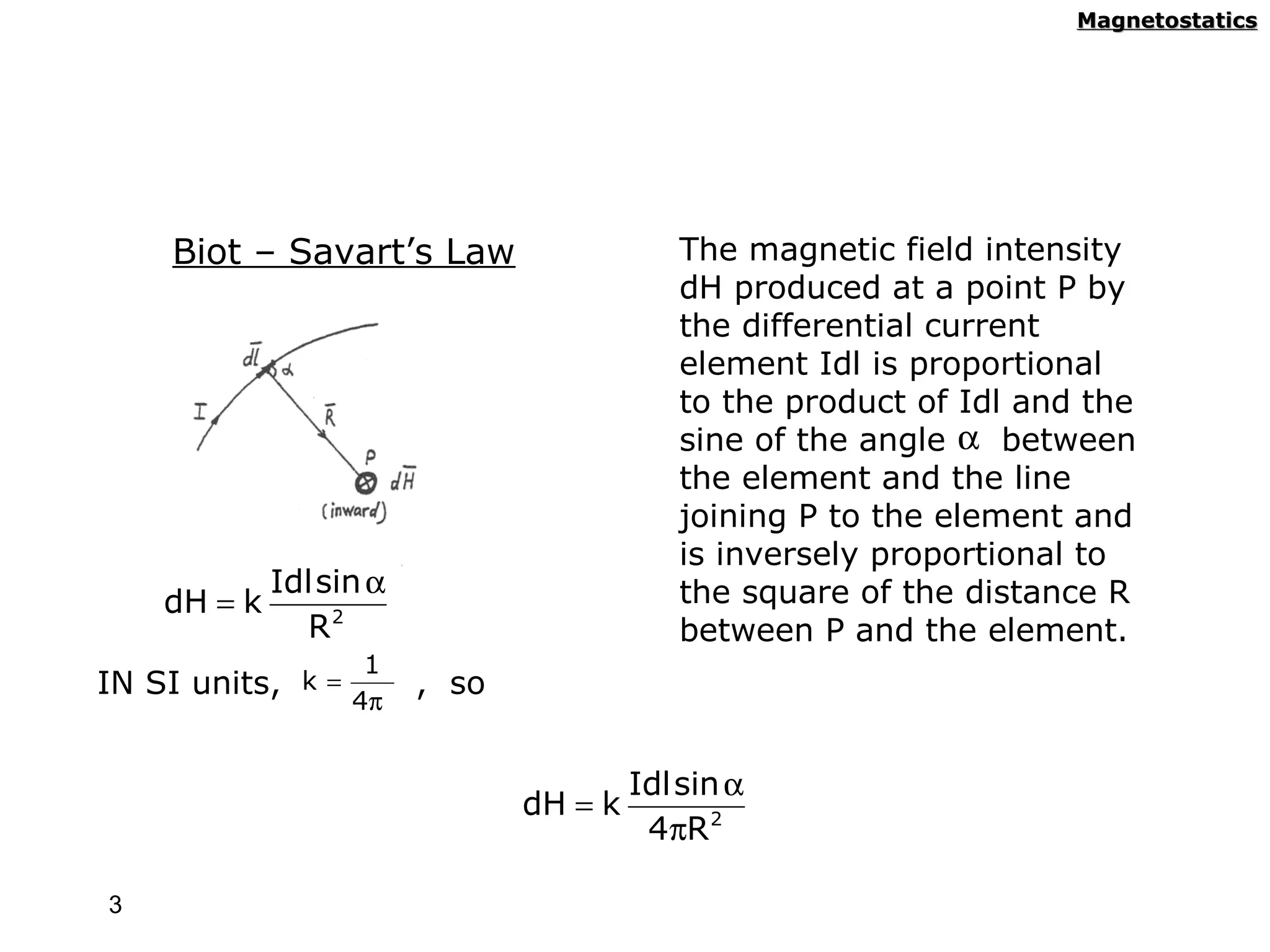

2) Biot-Savart's law describes the magnetic field produced by a current element, with the field proportional to the current and inversely proportional to the distance.

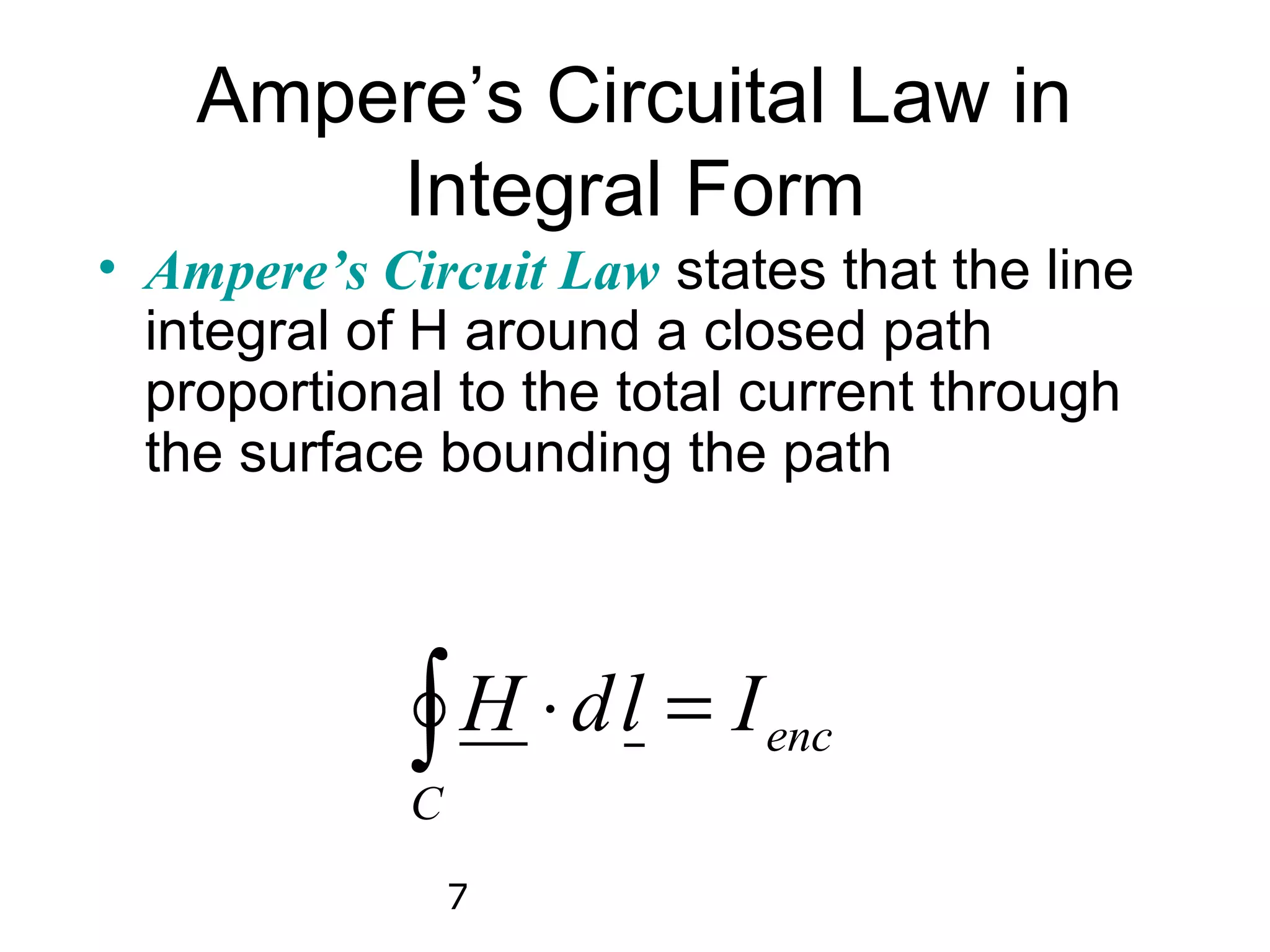

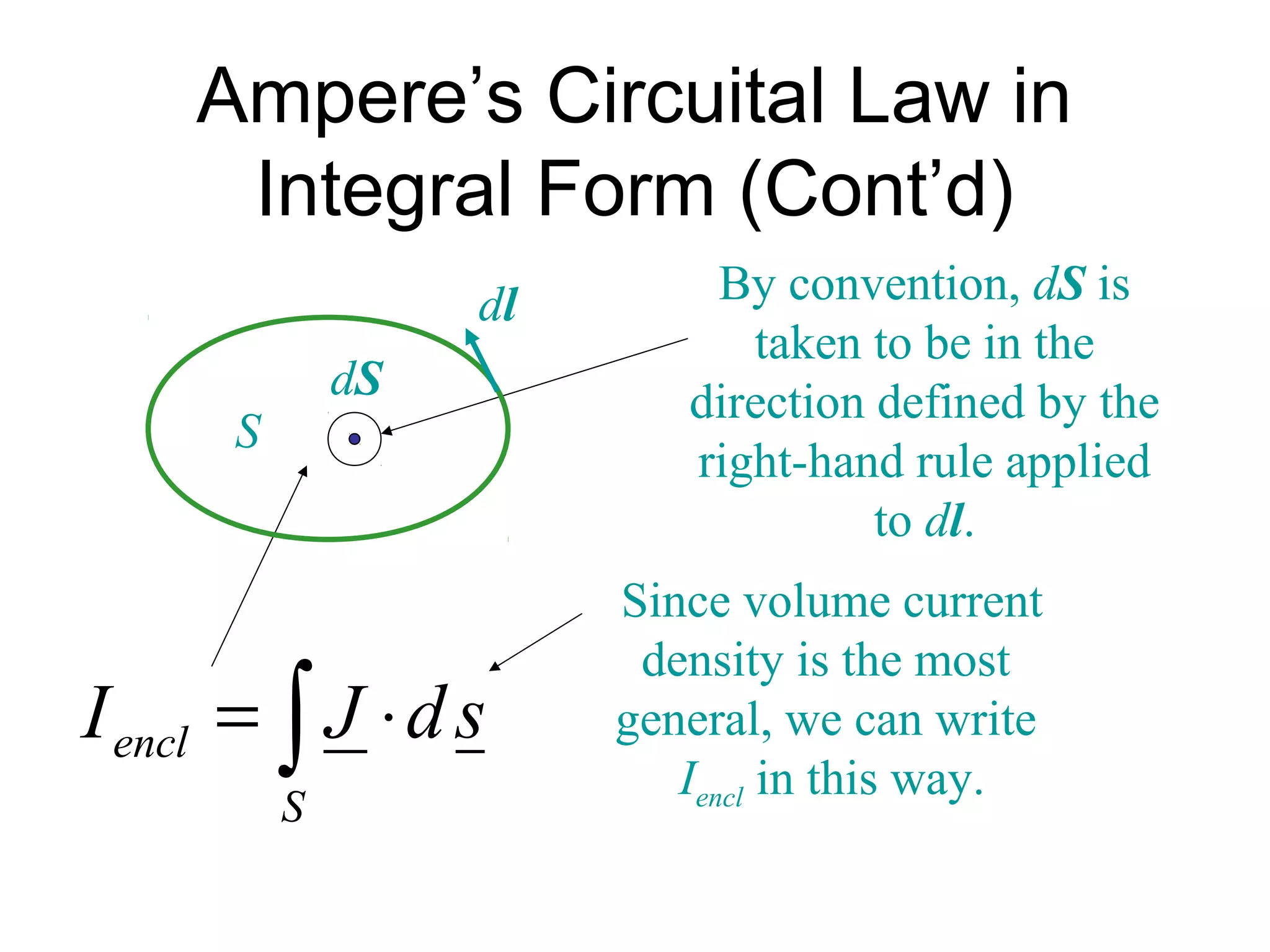

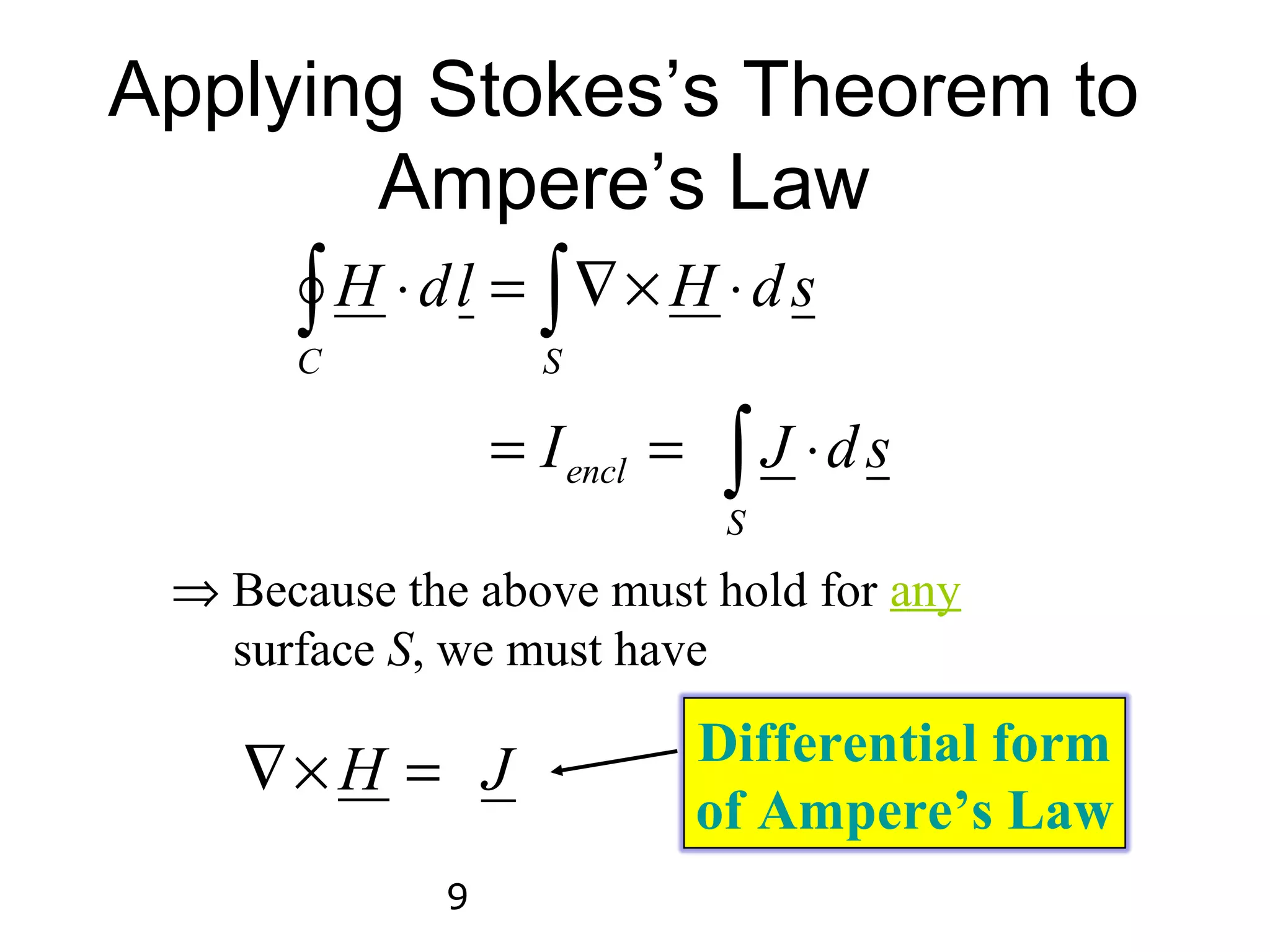

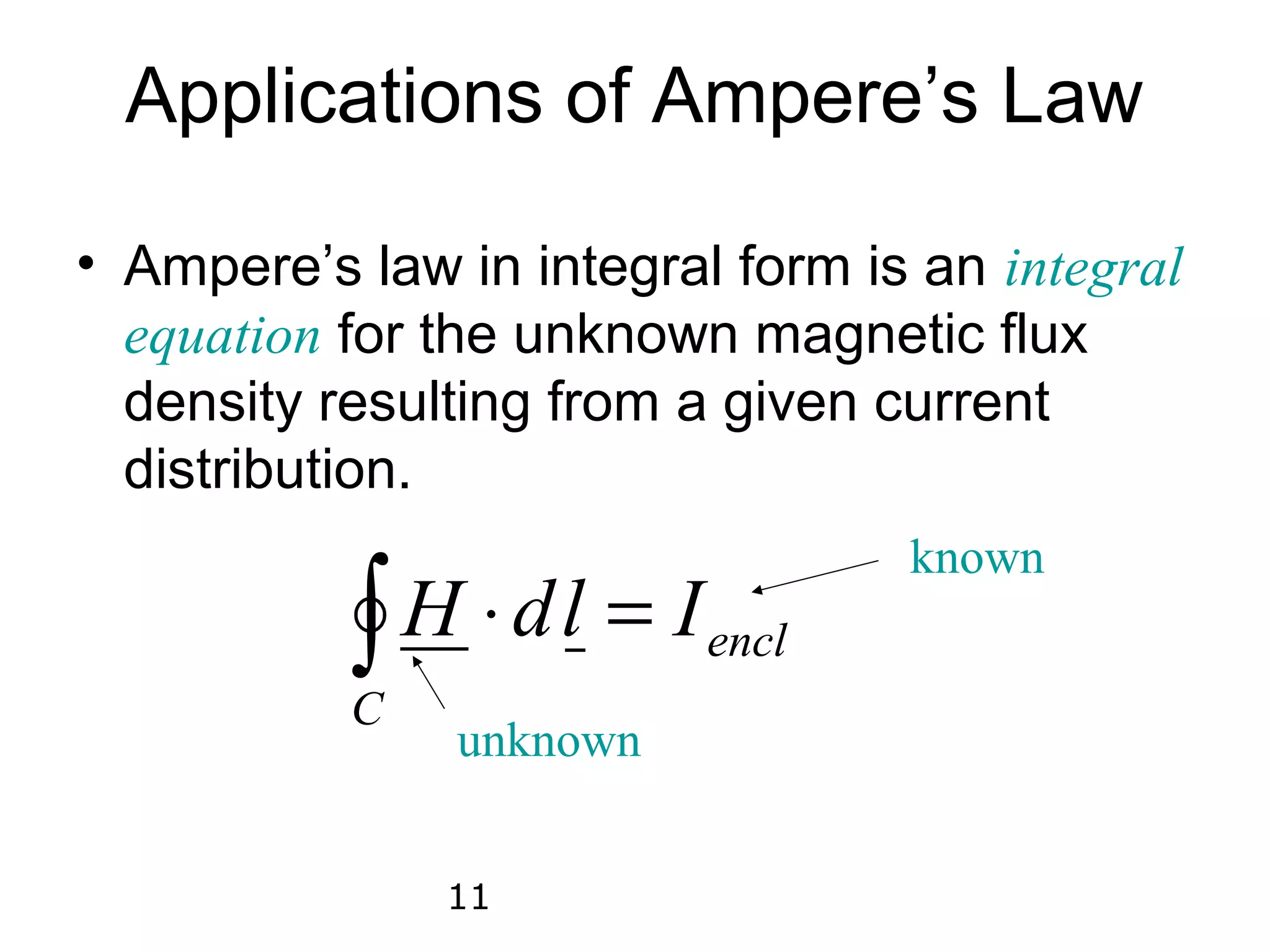

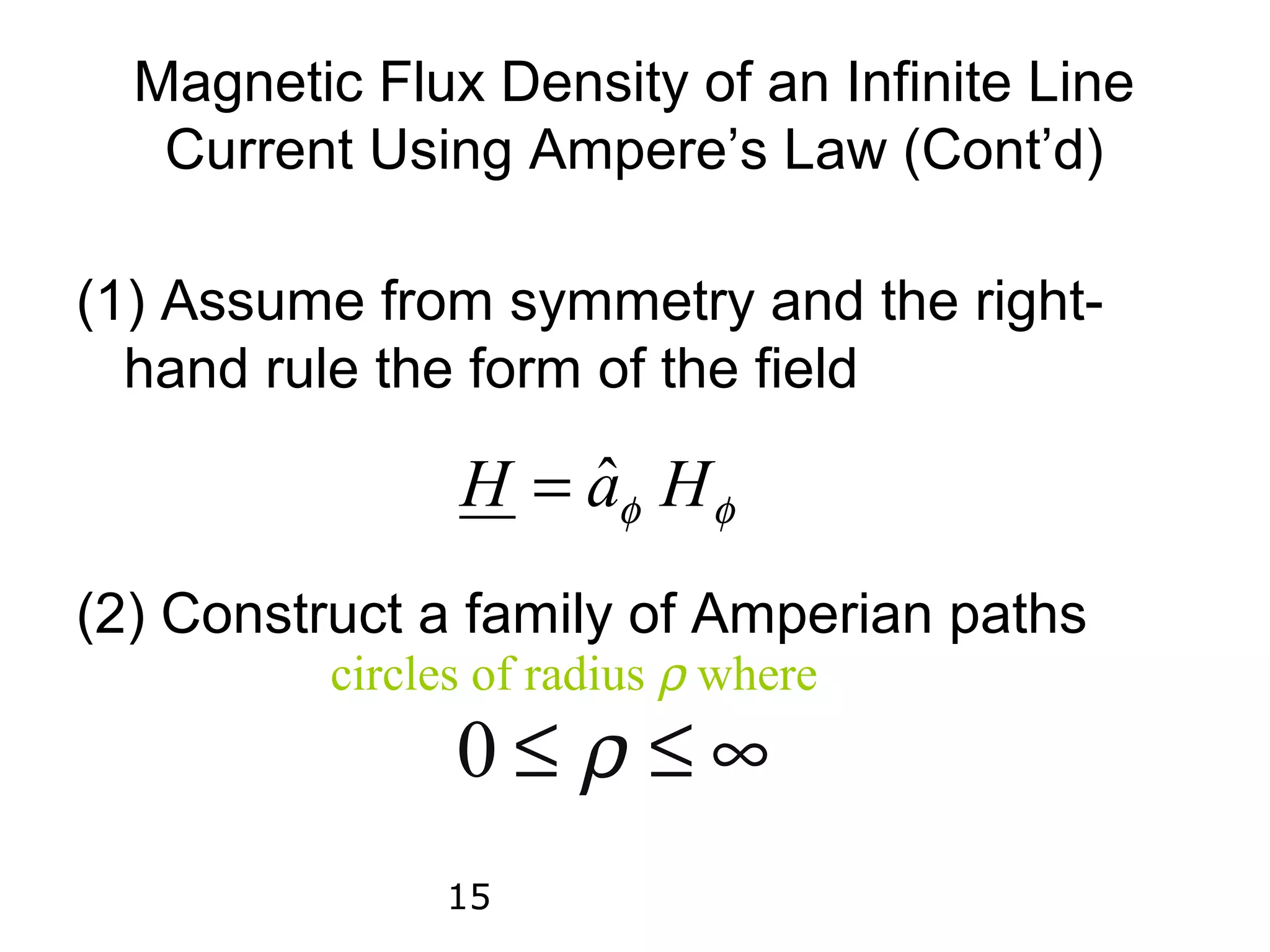

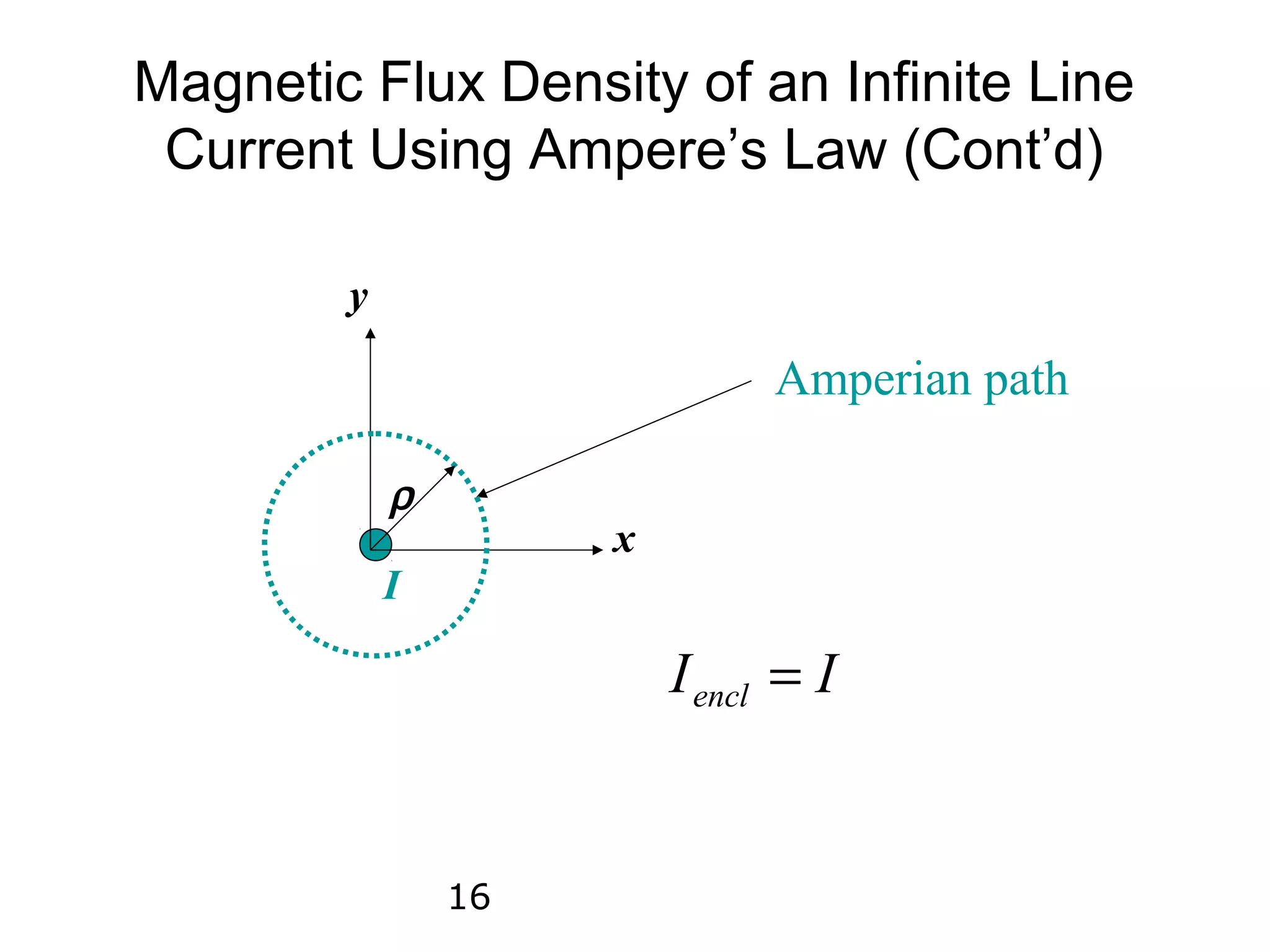

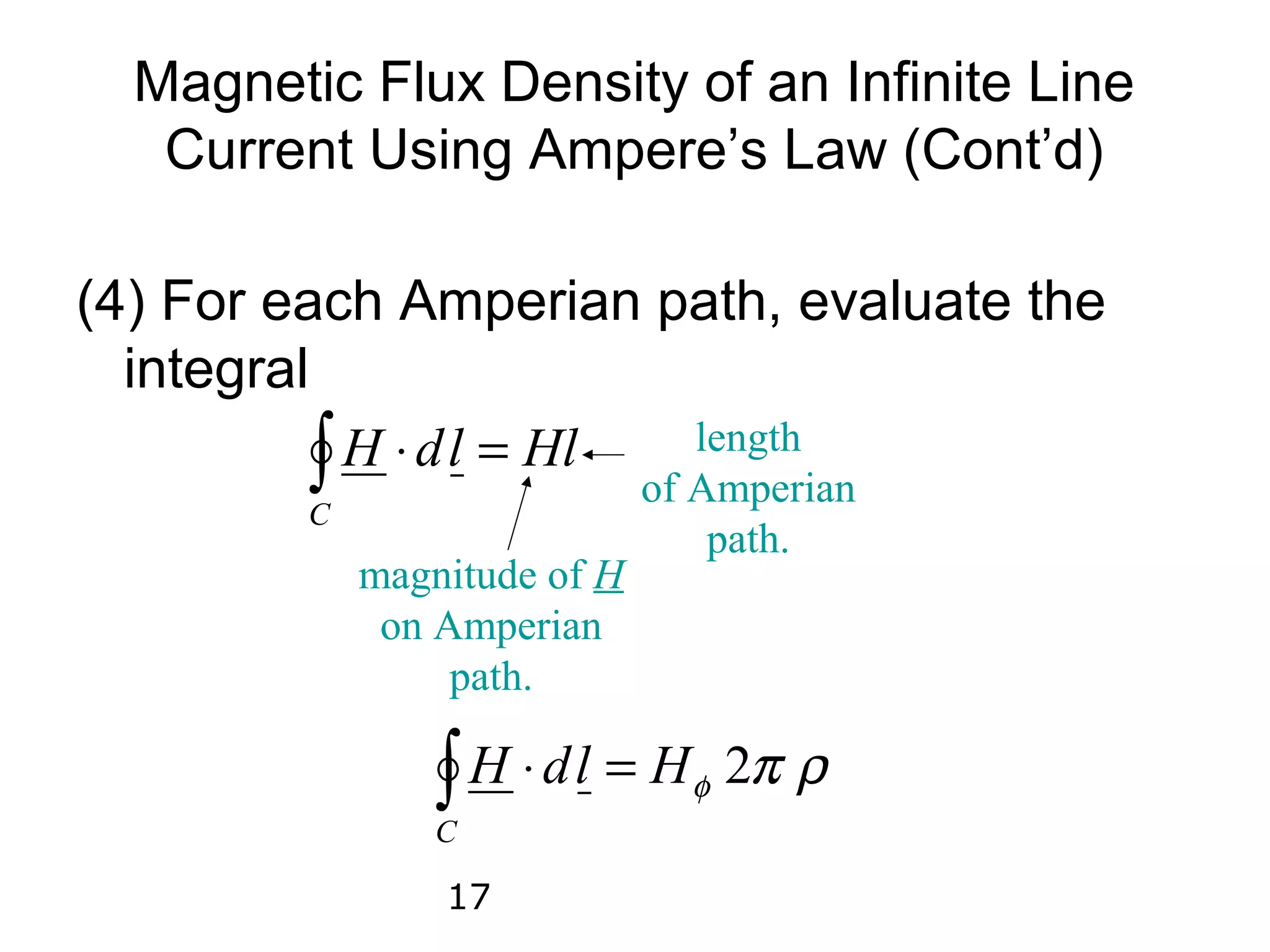

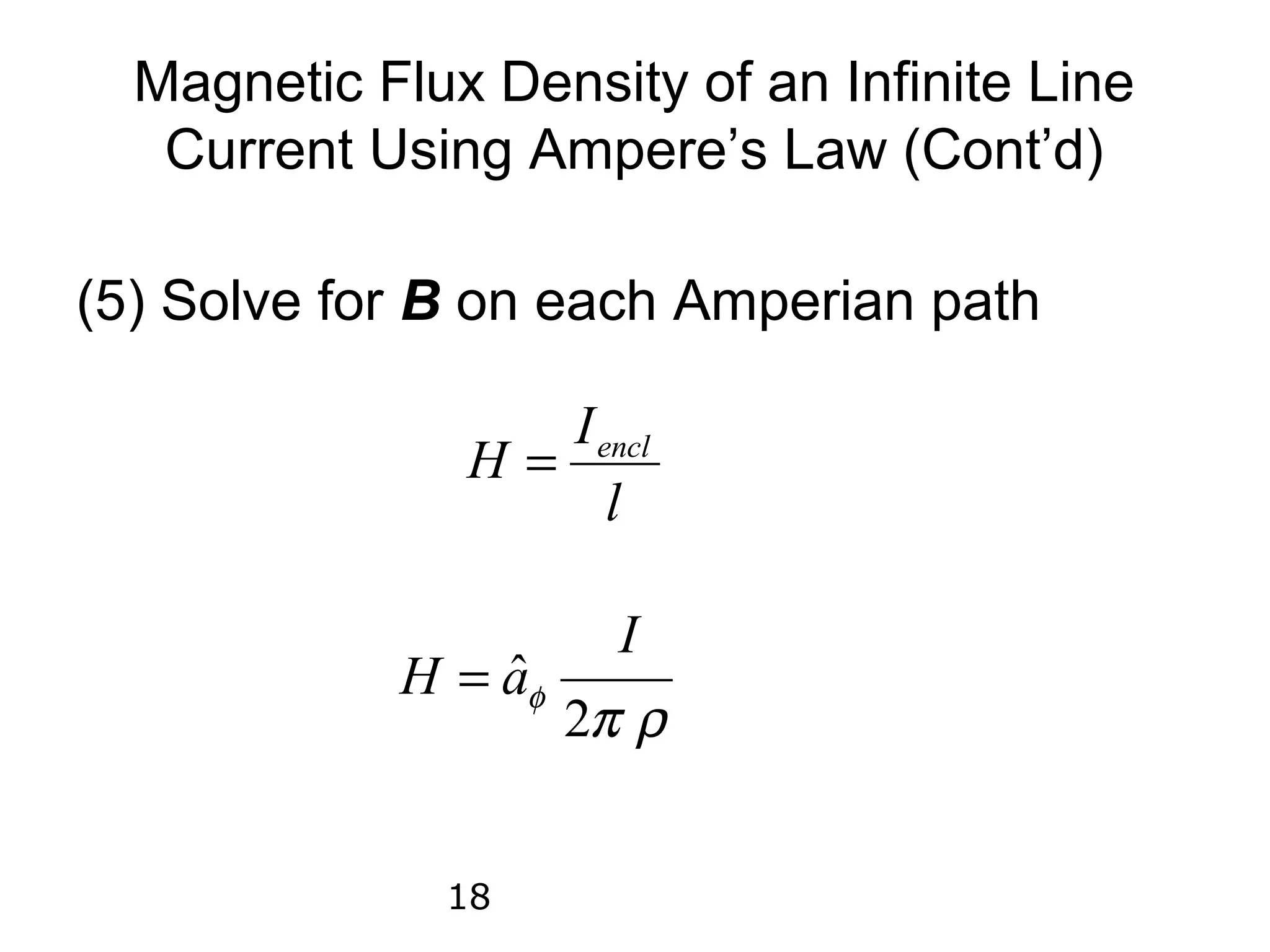

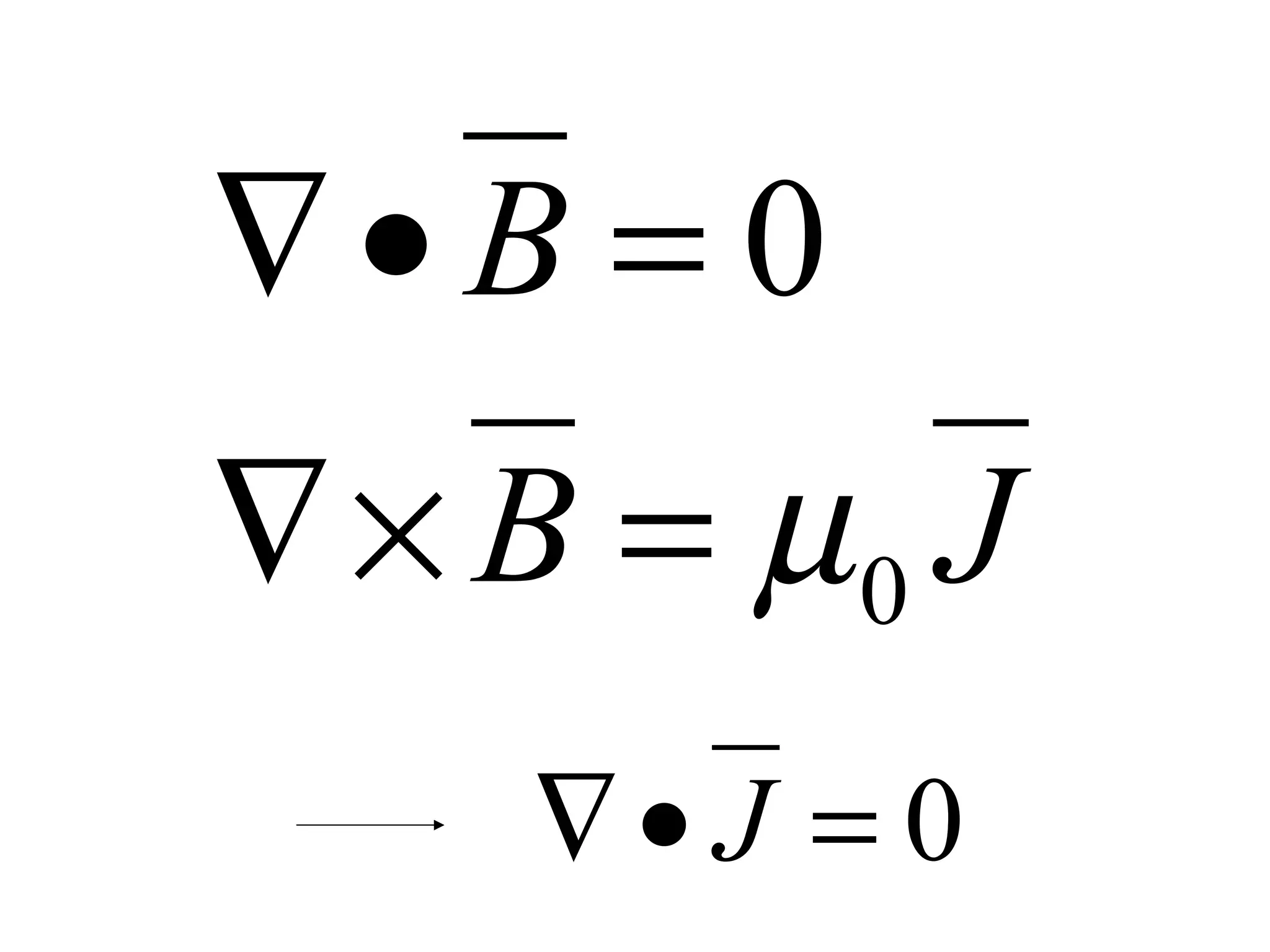

3) Ampere's law, in integral and differential form, relates the line integral of the magnetic field around a closed path to the total current passing through the enclosed surface.

![Magnetostatics

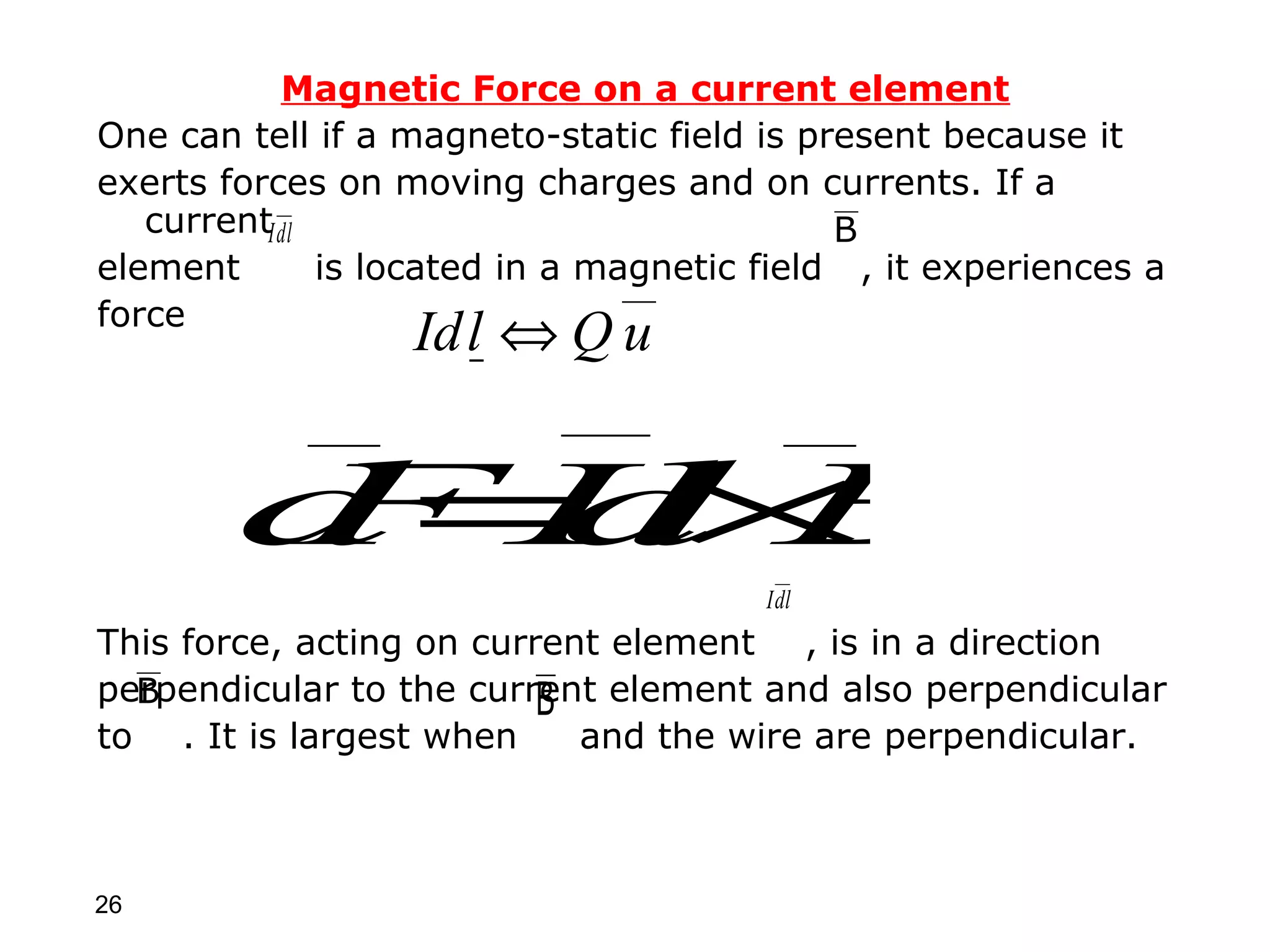

Using the definition of cross product ( A × B = AB sin θ AB an )

we can represent the previous equation in vector form as

I dl × ar I dl × R

dH = = R= R ar = R

4πR 2 4πR 3 R

The direction of d H can be determined by the right-hand rule

or by the right-handed screw rule.

If the position of the field point is specified by r and the

position of the source point by r ′

I (dl × ar ) I [dl × (r − r ′)]

dH = 2

= 3

4π r − r ′ 4π r − r ′

where er′r is the unit vector directed from the source point to

the field point, and r − r ′ is the distance between these two

points.

4](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/magnetostatics1-130416114320-phpapp01/75/Magnetostatics-1-4-2048.jpg)