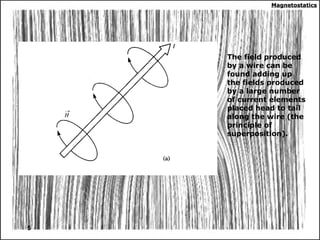

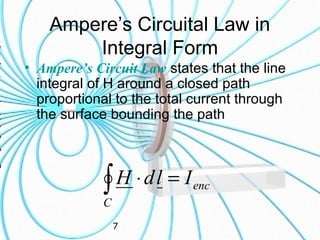

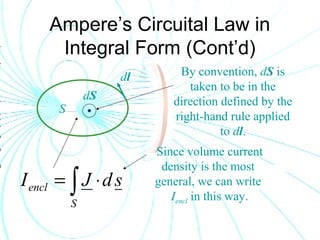

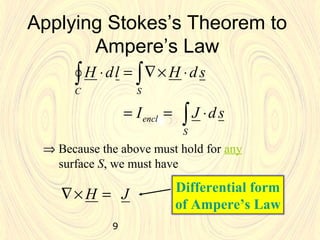

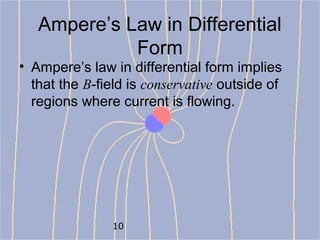

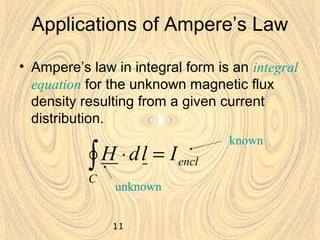

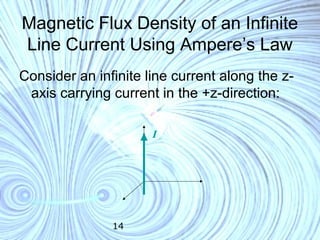

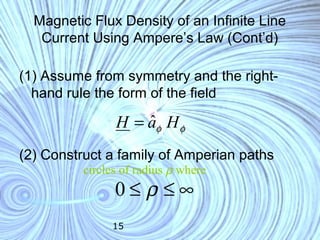

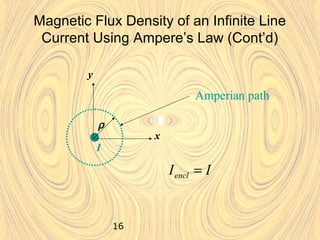

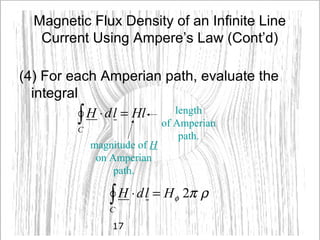

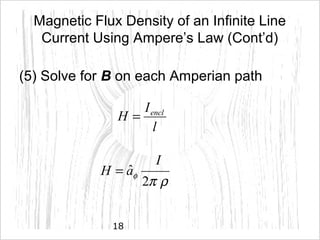

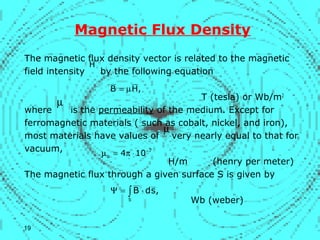

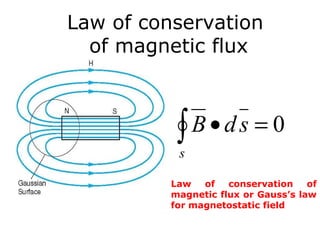

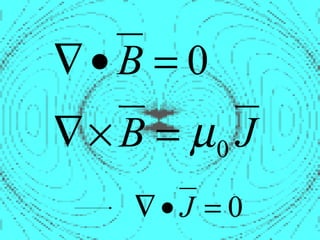

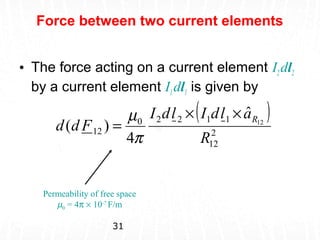

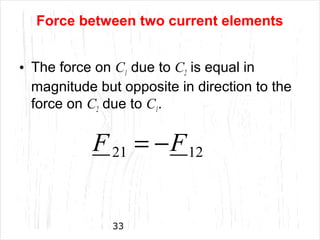

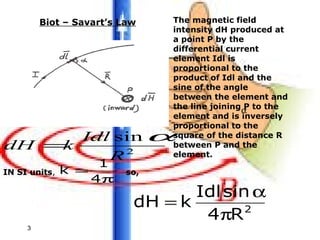

Magnetostatic fields are produced when charges are moving with constant velocity, such as in a current-carrying wire. Biot-Savart's law states that the magnetic field produced by a current element is proportional to the current and inversely proportional to the distance from the element. Ampere's law, the integral form of which relates the line integral of magnetic field around a closed path to the current through the enclosed surface, can be used to determine the magnetic field produced by symmetric current distributions.

(

rr

rrdlI

rr

adlI

Hd r

′−

′−×

=

′−

×

=

ππ

Hd

MagnetostaticsMagnetostatics

4](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/eft2-150220023726-conversion-gate01/85/Magnetostatics-4-320.jpg)