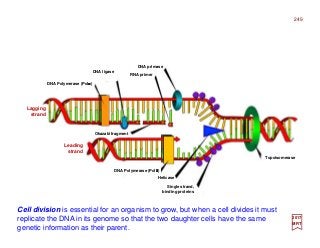

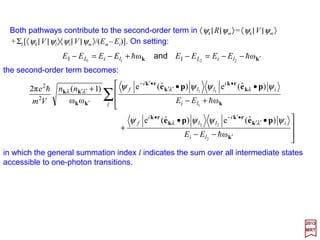

The document summarizes key details about the hydrogen atom and its electron orbital structure based on quantum mechanics. It provides:

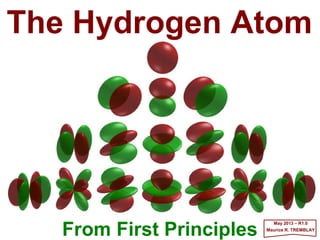

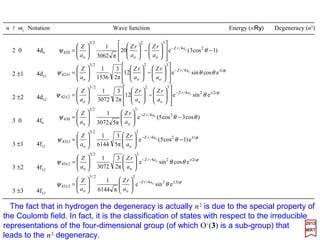

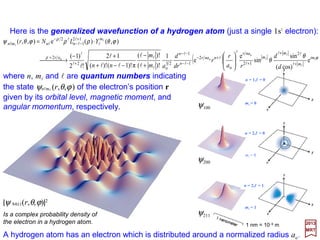

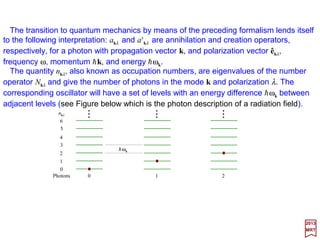

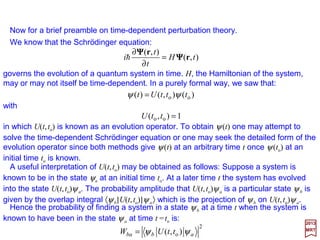

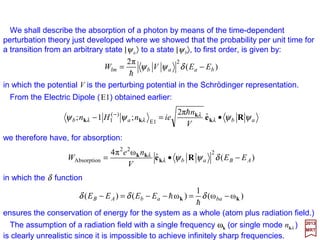

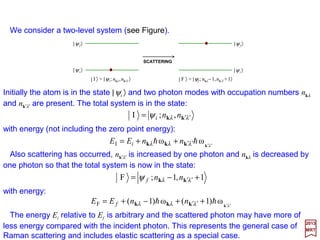

1) A direct observation of the electron orbital of a hydrogen atom placed in an electric field, obtained through photoionization microscopy. Interference patterns observed directly reflect the nodal structure of the wavefunction.

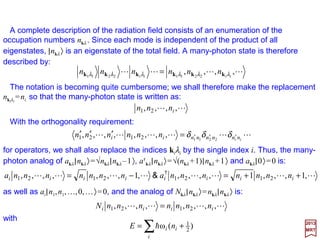

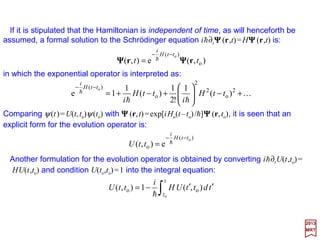

2) Calculated and measured probability patterns for the electron in different energy levels of the hydrogen atom are shown. Bright regions correspond to high probability of finding the electron.

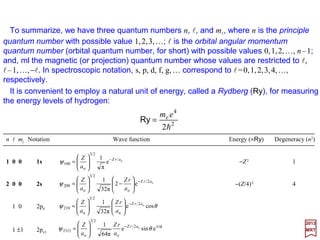

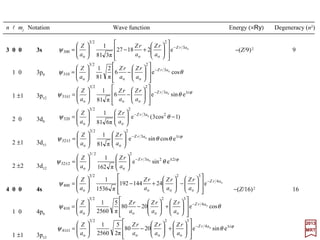

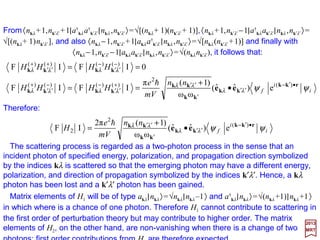

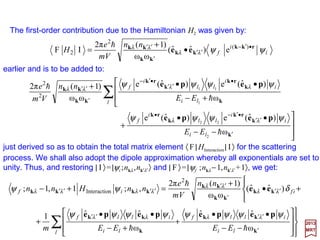

3) An overview of solving the radial, angular and azimuthal coordinate functions of the hydrogen atom through series expansion, as exact solutions have not been found. Approximate solutions can be obtained for more complex atoms like he

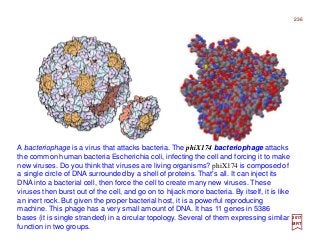

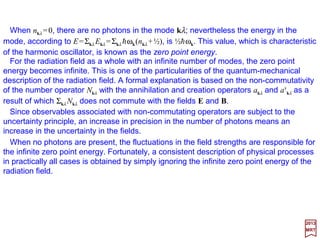

![Prolog

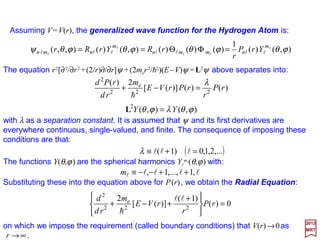

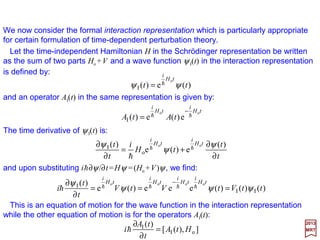

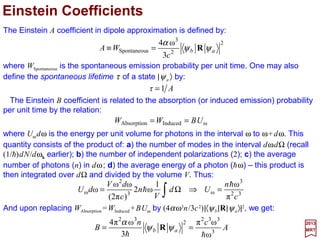

What you’re looking at is the first direct observation of an atom’s electron orbital — an atom’s actual wave

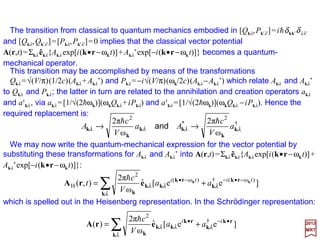

function! Up until this point, scientists have never been able to actually observe the wave function. Trying

to catch a glimpse of an atom’s exact position or the momentum of its lone electron has been like trying to

catch a swarm of flies with one hand. [c.f. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 213001 (2017)]

2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-hydrogen-130507131157-phpapp01/85/Part-V-The-Hydrogen-Atom-2-320.jpg)

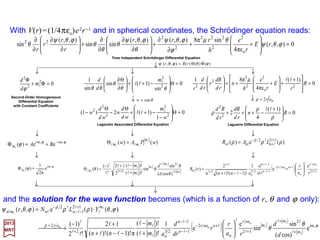

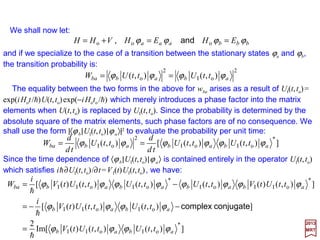

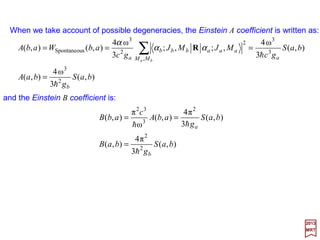

![Photoionization microscopy can directly obtain the nodal structure of the electronic orbital of a Hydrogen

atom placed in a static electric field. In the experiment, the Hydrogen atom is placed in the electric field E

and is excited by laser pulses. The ionized electron escapes from the atom and follows a particular tra-

jectory to the detector that is perpendicular to the field itself. Given that there are many such trajectories

that reach the same point on the detector, interference patterns can be observed […]. The interference

pattern directly reflects the nodal structure of the wavefunction. [c.f. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 213001 (2017)]

Calculated

Measured

3](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-hydrogen-130507131157-phpapp01/85/Part-V-The-Hydrogen-Atom-3-320.jpg)

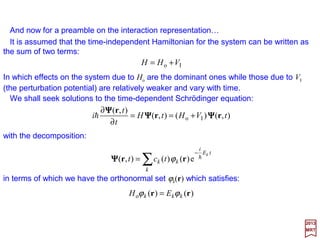

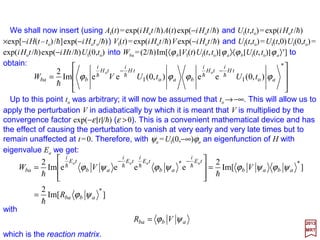

![with mo≡me the rest mass of the electron. By replacing E′ by E (non-relativistic energy);

eφ by −V,and p by −ih∇∇∇∇, the above equation becomes the static Schrödinger equation:

For an electron in a static field whose potential is ϕ, the Dirac equation (i.e., (E′+eϕ)ψ

={(1/2mo)[p+(e/c)A]2 +SMM[µS] Interaction−RE[p]−DT[p2]−SO[L••••S] Interaction}ψ – c.f.,

PART IV) without the higher-order relativistic corrections, simplifies and reduces to:

2017

MRT

ψψφ

o

2

2

)(

m

eE

p

=+′

in which the square of the angular momentum vector L is:

or, in spherical coordinates:

+=

+∇−= 22

e

22

e

2

)()()(

2

)( cmcEV

m

E prr ψψ

h

),,(),,()(

2

),,(

2 2

2

2

e

2

2

2

ϕθψϕθψϕθψ rrVE

rm

r

rrr

r L=−+

∂

∂

+

∂

∂

h

2

2

2

2

sin

1

sin

sin

1

ϕθθ

θ

θθ ∂

∂

+

∂

∂

∂

∂

=L

We recognize here the L2 operator from our discussion on spherical harmonics.

We will now consider a Hydrogen atom consisting of a single proton (Z=1) at its center

and an electron surrounding it. For hydrogen-like atoms (with Z>1), the reduced mass µ

=memp/(me +mp) should be used but can be neglected for this purpose of trivial illustration.

9](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-hydrogen-130507131157-phpapp01/85/Part-V-The-Hydrogen-Atom-9-320.jpg)

(

2

22

e

2

2

ϕθλϕθ

λ

YY

rP

r

rPrVE

m

rd

rPd

=

=−+

L

h

lllll ,1,...,1, ++−−≡m

Substituting these into the equation above for P(r), we obtain the Radial Equation:

0)(

)1(

)]([

2

22

e

2

2

=

+

+−+ rP

r

rVE

m

rd

d ll

h

The equation r2[∂2/∂r2 +(2/r)∂/∂r]ψ +(2me r2/h2)(E−V )ψ =L2ψ above separates into:

),()(

1

)()()(),()(),,( ϕθϕθϕθϕθψ l

ll

l

l lllllll

m

nmmn

m

nmn YrP

r

rRYrRr =ΦΘ==

10](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-hydrogen-130507131157-phpapp01/85/Part-V-The-Hydrogen-Atom-10-320.jpg)

![has solutions P(r)=exp(±ar) where a=√[−(2me/h2)E].

Solutions to this equation may be obtained by first considering the behavior at large r.

In the asymptotic region r →∞:

2017

MRT

)(e)(e)( o2

rfrfrP arra −−

==

where f (r) is a function to be determined by the Radial Equation and the boundary

conditions.

0)(

2)(

2

e

2

2

=+ rPE

m

rd

rPd

h

If E<0, exp(+ar)→∞ as r →∞. Since this violates (i.e., the ‘mathematical’ fact that the

exponential blows up at infinity!) the conditions (i.e., that it does not!) that the wave

function must be finite everywhere, it is not an acceptable solution (i.e.,itis not physically

possible!) On the other hand, exp(−ar)→0 as r →∞; it is therefore a possible solution.

If E >0, either sign in the exponent will satisfy the boundary conditions. We concentrate

on the case E<0, that is, the bound states of the atom.

The asymptotic behavior suggests that solutions to the Radial Equation be sought in

the form:

In the following slides, we will make use of the Bohr Radius (N.B., α =e2/hc=1/137):

11

( ) ( )MKSmorCGScm 11

2

e

2

o

o

8

e

2

e

2

o 1029.5

επ4

1052.0 −−

×==×===

em

a

cmem

a

hhh

α](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-hydrogen-130507131157-phpapp01/85/Part-V-The-Hydrogen-Atom-11-320.jpg)

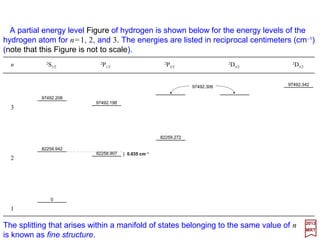

![0

5

10

ElectronVolt(eV)

13.60

n

1

2

3

4

5

∞ s p d f

LymanSeries

0

−5

−10

−13.60

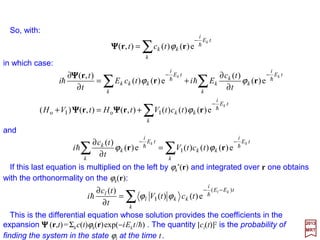

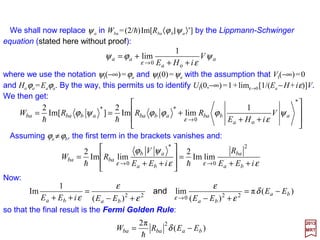

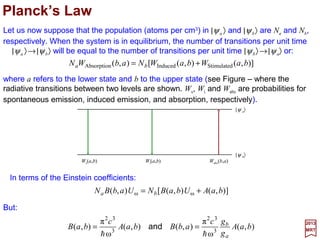

The first few energy levels of the Hydrogen

atom – without fine structure (i.e. corrections

due to nuclear spin angular momentum I ) or

using the reduced mass µ instead of me.

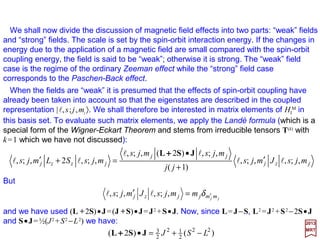

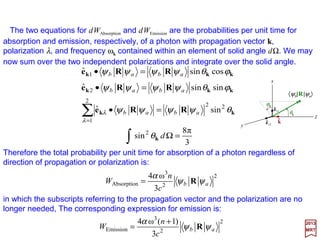

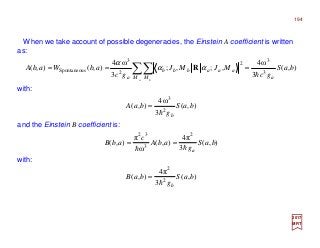

The energy levels of the Hydrogen atom are given by the

Balmer formula:

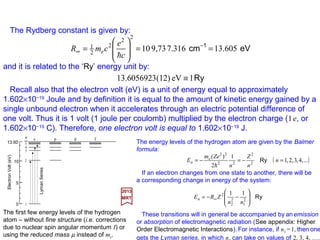

The Rydberg constant is given by:

and it is related to the ‘Ry’ energy unit by:

eV605.137.3169,7310

2

2

2

e2

1

==

= −

∞

1

cm

c

e

cmR

h

Ry1eV(12)13.6056923 ≡

Ry

−−= ∞ 2

1

2

2

2 11

nn

ZREn

( )...,4,3,2,1

1

2

)(

2

2

22

22

e

=−=−= n

n

Z

n

Zem

En Ry

h

If an electron changes from one state to another, there will be a

corresponding change in energy of the system:

These transitions will in general be accompanied by an emission

or absorption of electromagnetic radiation (c.f., Appendix: Higher

Order Electromagnetic Interactions). For instance, if n1 =1, then one

gets the Lyman series, in which n2 can take on values of 2, 3, 4, ….

Recall also that the electron volt [eV] is a unit of energy equal to approximately

1.602×10−19 J [Joule] and by definition it is equal to the amount of kinetic energy gained

by a single unbound electron when it accelerates through an electric potential difference

of one volt. Thus it is 1 Volt (1 Joule per Coulomb) multiplied by the electron charge (1e,

or 1.602×10−19 C [Coulomb]).Therefore,one electron volt is equal to: 1 eV =1.602×10−19 J.

2017

MRT

19](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-hydrogen-130507131157-phpapp01/85/Part-V-The-Hydrogen-Atom-19-320.jpg)

,(),( 2* lll

lll =

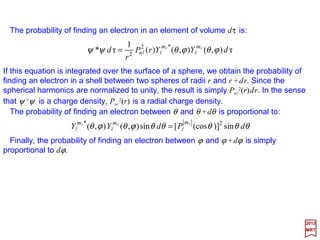

Finally, the probability of finding an electron between ϕ and ϕ +dϕ is simply

proportional to dϕ.

20](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-hydrogen-130507131157-phpapp01/85/Part-V-The-Hydrogen-Atom-20-320.jpg)

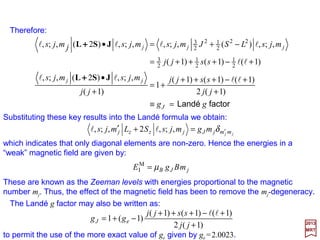

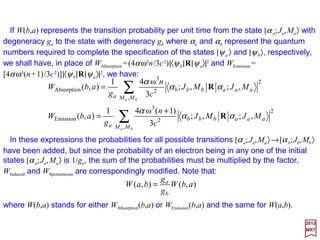

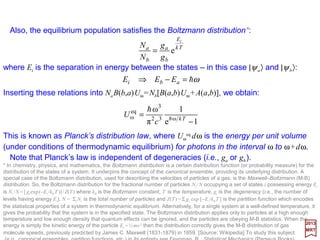

![Plot forY1

0,R10,and the probability densityψ100

∗ψ100=|ψ100|2 of the orbital [ yellow(+)/ blue

(−) on black] which is the probability of finding an electron around the atom’s nucleus.

2017

MRT

Plots for Y1

0 , R20, & |ψ200|2, Y1

0 , R21, & |ψ210|2, and for Y1

1 , R21, & |ψ211|2.

+½

−½

+½ −½

The maximum number

Nn of electrons in a

shell characterized by

principle number n is

given by twice (i.e. due

to spin) the number of

orbital stateswiththatn:

...,18,8,22

)12(2

2

1

0

==

+= ∑

−

=

n

N

n

n

l

l

21

+

−](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-hydrogen-130507131157-phpapp01/85/Part-V-The-Hydrogen-Atom-21-320.jpg)

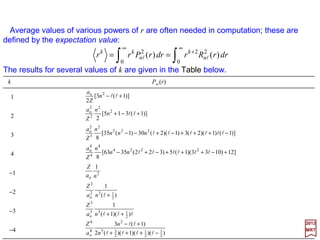

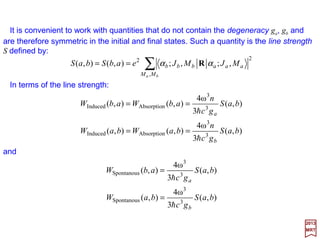

![Average values of various powers of r are often needed in computation; these are

defined by the expectation value:

2017

MRT

Expectation values 〈rk 〉 of rk for several values of k are given in the Table below.

∫∫

∞

+

∞

==

0

22

0

2

)()( drrRrdrrPrr n

k

n

kk

ll

〈rk〉

1

2

3

4

−1

−2

−3

−4

)]1(315[

2

2

2

2

2

o

+−+ lln

n

Z

a

k

)]1(3[

2

2o

+− lln

Z

a

)]1()1)(2(3)1)(2(30)1(35[

8

222

2

3

2

o

−+++−+−− llllllnnn

n

Z

a

]12)1033)(1(5)322(3563[

8

2224

4

4

4

o

+−+++−+− llllllnn

n

Z

a

2

o

1

na

Z

)½(

1

32

o

2

+lna

Z

lll )½)(1(

1

33

o

3

++na

Z

)½)(½)(1)((2

)1(3

2

35

2

4

o

4

−+++

+−

llll

ll

n

n

a

Z

24](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-hydrogen-130507131157-phpapp01/85/Part-V-The-Hydrogen-Atom-24-320.jpg)

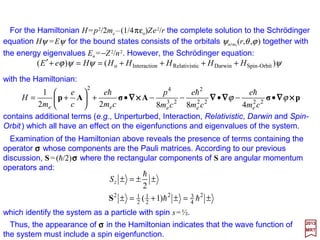

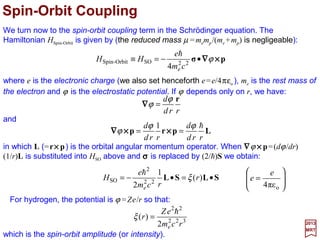

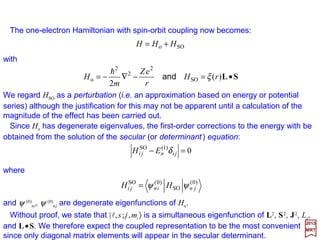

![For the Hamiltonian H=p2/2me −(1/4πεo)Ze2/r the complete solution to the Schrödinger

equation Hψ =Eψ for the bound states consists of the orbitals ψnlml

(r,θ,ϕ) together with

the energy eigenvalues En =−Z2/n2. However, the Schrödinger equation:

2017

MRT

with the Hamiltonian (see the Appendix – Higher Order Electromagnetic Interactions):

pAAp ××××∇∇∇∇ΣΣΣΣ∇∇∇∇∇∇∇∇××××∇∇∇∇ΣΣΣΣ ϕϕ •−•−−•+

+= 22

e

22

e

2

23

e

4

e

2

e 48822

1

cm

e

cm

e

cm

p

cm

e

c

e

m

H

hhh

ψψψϕ )()( Orbit-SpinDarwinicRelativistnInteractioo HHHHHHeE ++++==+′

contains additional terms (e.g., Unperturbed, Interaction, Relativistic, Darwin and Spin-

Orbit) which all have an effect on the eigenfunctions and eigenvalues of the system.

which identify the system as a particle with spin s=½.

±=±+=±

±±=±

222

¾)1½(½

½

hh

h

S

zS

Examination of the Hamiltonian above reveals the presence of terms containing the

operator ΣΣΣΣ whose components are the Pauli matrices, σσσσ =[σ1,σ2,σ3] (where σ1

REAL/SYM =

+1, σ2

COMPLEX/ANTI = mi, and σ3

REAL/DIAG

PARITY =±1). According to our previous discussion,

S =½hΣΣΣΣ where the rectangular components of S are angular momentum operators and:

Thus, the appearance of ΣΣΣΣ in the Hamiltonian indicates that the wave function of

the system must include a spin eigenfunction.

25](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-hydrogen-130507131157-phpapp01/85/Part-V-The-Hydrogen-Atom-25-320.jpg)

![In the spin-½ [in units of h] case, we saw earlier that:

2017

MRT

=

=−=−

=

=+=+

=

−

+

χ

χ

1

0

½,½

0

1

½,½

, sms

The one-electron spin function is:

−=

+=

==

−

+

½

½

)(

s

s

sm

m

m

ms

for

for

χ

χ

ξξ

whereas the (one-electron) spin orbital is:

)()(),,,(),,( ssmmn mmmnr s

ξrξ ψψϕθψ == ll ll

It shall be understood that an integral involving spin orbitals implies a spatial integration

as well as a summation over spin coordinates. Also, we now have a degeneracy of 2n2

associated with the addition of spin eigenfunctionψnlmlms

(r,θ,ϕ,±½) andweuse |l,s;ml ,ms 〉

to identify the angular and spin parts of the wave function. Degenerate eigenfunctions

may be combined linearly to form other sets in a coupled representation of degenerate

eigenfunctions using the Clebsch-Gordan coefficients Cj

mlms

=〈l,s;ml,ms |l,s; j,mj 〉:

∑∑ ==

s

s

s mm

s

j

mm

mm

jssj mmsmjsmmsmmsmjs

l

l

l

lll lllll ,;,,;,,;,,;,,;, C

26](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-hydrogen-130507131157-phpapp01/85/Part-V-The-Hydrogen-Atom-26-320.jpg)

![To see how this works out, let:

2017

MRT

or:

)( 222

2

1

SLJ −−=•SL

∫∫

∞∞

====

0

2

0

2

)()()()(,)(,)( rdrPrrdrrRrnrnr nnn lll ll ξξξξξ

3322

e

22

3322

e

22

1

2

,

1

,

2

)(

rrcm

eZ

n

r

n

rcm

eZ

r

h

ll

h

==ξ

Using the coupled representation:

The Hamiltonian HSO =ξ(r)L•S also contain the radial function ξ(r). So, to obtain the

energy corrections it is also necessary to evaluate the expectation value of ξ(r):

From the Table for 〈rk 〉 (with k=−3):

SLSLJSLJ •++== 2222

and++++

jjss

jjjj

ssjj

mjsSLJmjsmjsmjs

′′′+−+−+=

−−′′′′=•′′′′

δδδ llll

llll

)]1()1()1([

,;,,;,,;,,;,

2

1

222

2

1SL

In hydrogen, ξ(r) is given by ξ(r)=Ze2h2/2me

2c2r3 in which case:

lll )½)(1(

11

23

o

3

3

++

=

na

Z

r

31](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-hydrogen-130507131157-phpapp01/85/Part-V-The-Hydrogen-Atom-31-320.jpg)

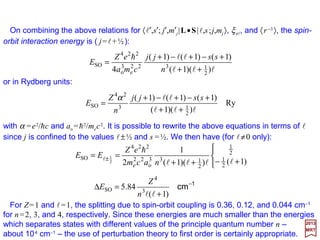

![From the relation 〈l′,s′; j′,m′j|L•S|l,s;j,mj 〉=½[ j( j+1)−l(l+1)−s(s+1)]δl′lδs′sδj′j it is seen

that the matrix elements vanish unless:

These are the selection rules for spin-orbit coupling. Also, these are also valid:

0)(0 =+∆=∆=∆=∆ sj mmmj ll and

The Table below lists values of the 〈1,½; m′l,m′s|L•S|1,½;ml,ms 〉 matrix elements for p

states of ξnl= 〈n,l|ξ(r)|n,l〉 (and shortened to |ml ,ms 〉 since l=1 and s =½ for all states).

½,1−

2017

MRT

½,1

½,1 ½,0 ½,0 − ½,1− ½,1−−

½,1 −

½,0

½,0 −

½,1−

½,1 −−

2

1

2

1

−

2

1

2

1

0

0

2

1

2

1

2

1

−

2

1

1,01,0 ±=∆±=∆ smm andl

33](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-hydrogen-130507131157-phpapp01/85/Part-V-The-Hydrogen-Atom-33-320.jpg)

![The most important interaction between a nucleus of charge Ze and an electron of

charge e is, of course, the Coulomb interaction −Ze2/r. All other interactions between a

nucleus and the electrons of the same atom are classified as hyperfine interactions, and

among these the most important are the ones that arise as a result of a nucleus

possessing a magnetic dipole moment (i.e., associated with the nuclear spin) and an

electric quadrupole moment (i.e., associated with a departure from a spherical charge

distribution in the nucleus). In the former case the nuclear magnetic dipole moment

interacts with the electronic magnetic dipole moments which are associated with the

electronic orbital and/or spin angular momenta. In the latter, the interaction occurs when,

at the position of the nucleus, the electronic charge distribution produced an electric field

gradient with which the nuclear electric quadrupole moment can interact.

Magnetic field created by the proton. Outside

the proton, the field B is that of a dipole – µµµµI;

inside, the field Bi depends on the exact

partition of the magnetism of the proton.

5

22

o

5

o

5

o 3

π4

µ

3

π4

µ

3

π4

µˆˆˆ

r

rz

B

r

zy

B

r

zx

BBBB zyxzyx

−

===⇔++= IIIkjiB µµµ and,

The magnetic field inside the proton, Bi, is given by (SI system):

Consider a proton of radius ro. The partition of magnetism

inside the proton creates a field B outside which can be

calculated by attributing to the proton a magnetic moment µµµµI

(which is taken to be parallel to the z-axis – see Figure).

Hyperfine Interactions

z

y

x

B

µµµµI

Bi

3

o

o 2

π4

µ

r

Bi Iµ=

2017

MRT

where µo is the magnetic permeability of free space.

ro

The external field is thus purely dipolar.

For r >> ro, we obtain the components of B (by calculating the

rotational of AI = (µo/4π)[(µµµµI ×××× r)/r3]) (SI system):

51](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-hydrogen-130507131157-phpapp01/85/Part-V-The-Hydrogen-Atom-51-320.jpg)

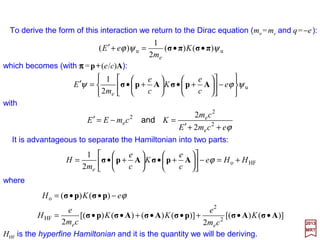

![To derive the form of this interaction we return to the Dirac equation(mo ≡me and q≡−e):

with:

2017

MRT

It is advantageous to separate the Hamiltonian into two parts:

where:

u

e

u )()(

2

1

)( ψψφ ππ ••=+′ ΣΣΣΣΣΣΣΣ K

m

eE

φecmE

cm

KcmEE

++′

=−=′ 2

e

2

e2

e

2

2

and

HFo

e2

1

HHe

c

e

K

c

e

m

H +=−

+•

+•= φApAp ΣΣΣΣΣΣΣΣ

φeKH −••= )()(o pp ΣΣΣΣΣΣΣΣ

HHF is the hyperfine Hamiltonian and it is the quantity we will be deriving.

u

e2

1

ψφψ

−

+•

+•=′ e

c

e

K

c

e

m

E ApAp ΣΣΣΣΣΣΣΣ

which becomes (with ππππ=p++++(e/c)A):

52

and:

)]()[(

2

)]()()()[(

2 2

e

2

e

HF AApAAp ••+••+••= ΣΣΣΣΣΣΣΣΣΣΣΣΣΣΣΣΣΣΣΣΣΣΣΣ K

cm

e

KK

cm

e

H](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-hydrogen-130507131157-phpapp01/85/Part-V-The-Hydrogen-Atom-52-320.jpg)

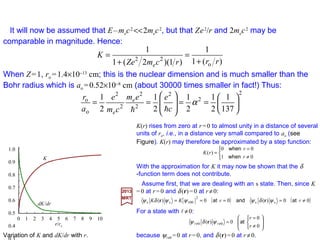

![We concentrate on HHF which contains the entire dependence on the vector potential

A and the last term on the right is quadratic in A; it may therefore be neglected in a first

approximation.

2017

MRT

Also, since:

we have:

and HHF becomes:

)()(])()([)(()( r

r

rprrrrp f

rrd

dK

ifKKffKifKifΚ hhh −=+−=−= ∇∇∇∇∇∇∇∇∇)∇)∇)∇)

rrd

dK

K

r

=∇∇∇∇

rdr

dK

iKΚ

r

pp h−=

••+••−••= ))(())((

1

))((

2 e

HF pAArAp ΣΣΣΣΣΣΣΣΣΣΣΣΣΣΣΣΣΣΣΣΣΣΣΣ K

rdr

dK

iK

cm

e

H h

The potential φ is assumed to be a function of r only (i.e., φ(r)) which means that K

depends only on r (i.e., K(r)) so that:

Using the identity (ΣΣΣΣ•A)(ΣΣΣΣ•B)=A•B+iΣΣΣΣ•(A××××B), HHF is converted to:

)]([

1

)()(

2 e

HF ArArpAAppAAp ××××ΣΣΣΣ××××××××ΣΣΣΣ •+•−+•+•+•= i

rdr

dK

iKiK

cm

e

H h

53](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-hydrogen-130507131157-phpapp01/85/Part-V-The-Hydrogen-Atom-53-320.jpg)

![With these relations, we get:

Finally:

2017

MRT

When these relations are included into our last development for HHF one obtains:

in which:

cm

e

B

e22

hh

== µandΣΣΣΣS

)(π4

3

)( 35

2

rµ

µr

rµ

µµµ

A δΙΙΙΙ

ΙΙΙΙ

ΙΙΙΙ

ΙΙΙΙΙΙΙΙΙΙΙΙ

++++−−−−∇∇∇∇∇∇∇∇××××∇∇∇∇××××∇∇∇∇××××∇∇∇∇

rrrrr

•=

∇−

•=

=

333

)(

])[(

1

][

1

rrrr

rµrµ

rµrµrrrµrAr ΙΙΙΙΙΙΙΙ

ΙΙΙΙΙΙΙΙΙΙΙΙ −−−−))))))))((((−−−−))))××××((((××××××××

•

=••==

••

+

•

+

•+

••

+

•

= 4253HF

))((

2)(π4

))((3)(

2

rrrd

dK

rr

KH BB

rSrµSµ

Sµr

rSrµSLµ II

I

II

µδµ

−−−−

with ΣΣΣΣ whose componentsare Pauli matricesσσσσ=[σ1,σ2,σ3]. We now examine K and dK/dr.

rZecmE

cm

K 22

e

2

e

2

2

++′

=

If ϕ is replaced by Ze/r, we have:

56](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-hydrogen-130507131157-phpapp01/85/Part-V-The-Hydrogen-Atom-56-320.jpg)

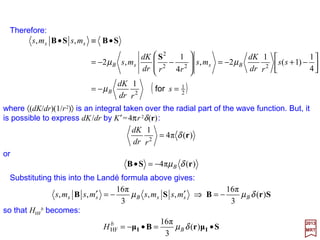

![An alternative expression for the magnetic hyperfine Hamiltonian is obtained by

transforming the dipole-dipole part by means of the Landé formula. Let

Then:

2017

MRT

and:

But since (L –S)•J=(L –S)•(L+S)=L2 −S2 and recalling that | j,mj〉=|l,s; j,mj 〉 is an

eigenfunction of L2 and S2 (as well as J2 and Jz ), we get 〈 j;mj|(L–S)•J| j;mj〉=

〈 j,mj|L2 −S2 | j,mj〉=l(l+1)−s(s+1). Also r•J=r•(L+S)=r•(r××××p)/h+r•S=r•S=S•r.

Therefore, as we obtained earlier (r•J)(r•S)=(r•S)(r•S)=(1/4)(ΣΣΣΣ•r)(ΣΣΣΣ•r)=r2/4.

Integrating over the radial part of the wave function we obtain 〈 j,mj |B′•J| j,mj〉=

−2µB[l(l+1)−s(s+1)+¾]〈1/r3〉=−2µBl(l+1)〈1/r3〉 (for s=½). so that:

•

+−=′ 53

)(3

2

rr

B

rSrSL

B

−−−−

µ

( )½

1

)1(

)1(

2 3

=

+

+

−=′ s

rjj

B for

ll

µB

sjj

jj

jj mjmj

jj

mjmj

mjmj ′

+

•′

=′′ ,,

)1(

,,

,, J

JB

B

jjBjj mj

rr

mjmjmj ,

))((3

,2,, 53

rSJrSL

SB

••

+−=•′

−−−−

µ

63](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-hydrogen-130507131157-phpapp01/85/Part-V-The-Hydrogen-Atom-63-320.jpg)

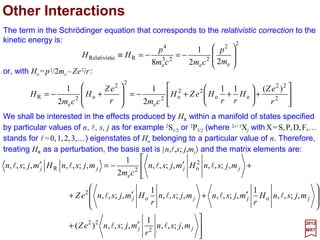

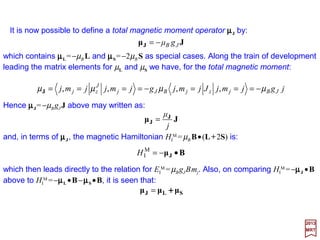

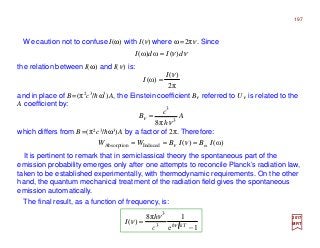

![For Hydrogen in an s state only the contact term is effective. Since l=0, J may be

replaced by S so that:

and, since the spin of the proton is I=½, we have also s=½ thus F=0 & 1. Hence:

which indicates that the only diagonal elements are non-zero. For the two possible

values of F, the energies are:

( )

( )

=−=−

==

=

0

4

3

π4

1

4

1

3

π4

2

100

2

100

FA

FA

E

FB

FB

ψγµ

ψγµ

h

h

)(

2

1 222

ISFSI −−=•

−+=

+−+−+=−−=•

2

3

)1(

2

1

)]1()1()1([

2

1

,)(½,,, 222

FF

IIssFFmFmFmFmF FFFF ISFSI

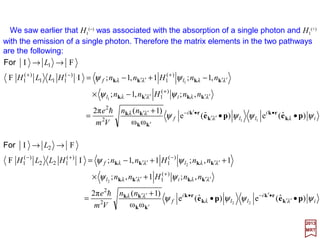

2S1/2

0.047 cm−1 (or 21 cm)

F = 1

F = 0

n = 1

Magnetic hyperfine splitting of the ground

state of hydrogen. The entire splitting is due

to the Fermi contact term geµBgNµN (i.e., a

quantum effect.).

o

2

100

3

61

3

6π1

a

AE B

FB

h

h

γµ

ψγµ ===∆

For hydrogen, |ψ 100|2 =1/πao

3 (ao =0.529×10−8 cm), γh =µN gN =

5.05×10−23 erg/GHz and with µB =0.927×10−20 erg/GHz, the

difference in energy between the two levels for E is:

2017

MRT

as show in the Figure. If we set ∆E= hν, the frequency ν is

1420.4058 MHz, which corresponds to a wavelength of 21 cm.

65](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-hydrogen-130507131157-phpapp01/85/Part-V-The-Hydrogen-Atom-65-320.jpg)

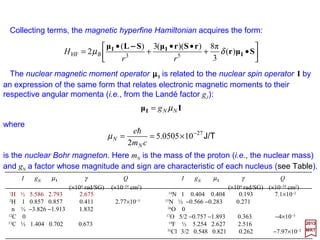

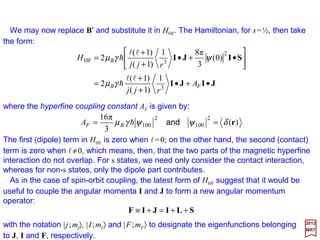

![Next, we consider the dipole-dipole term in our last expression for HHF.

Also, we have I•J=½(F2 −I2 −J2) and 〈F,mF|I•J|F,mF〉=½[F(F+1)−I(I+1)− j( j+1].

Again, only the diagonal matrix elements are non-zero. Therefore the energies are given

by:

lll )½)(1(

11

33

o

3

3

++

=

na

Z

r

For hydrogen, we use from the Table for 〈rk〉:

)]1()1()1([

)½)(1(33

o

3

+−+−+

++

= IIjjFF

jjna

Z

E B

l

hγµ

2017

MRT

66](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-hydrogen-130507131157-phpapp01/85/Part-V-The-Hydrogen-Atom-66-320.jpg)

Yl

ml*(θ1,ϕ1)Yl

ml (θ2,ϕ2) – we get:

in which re is the position vector of the electron, rp is the position vector of the p-th

proton, and the sum is taken over all Z protons.

∑−=

=•=•

l

l

ll

llll

l

ll

m

mm

YY ),(),(),(),( eepp

*

ee

)(

pp

)()(

e

)(

p ϕθϕθϕθϕθ YYYY

∑

∞

=

+

>

<

•

+

=

0

1

)(

p

)(

e

pe

12

1

π4

1

l

l

l

ll

l r

r

YY

rr −−−−

Substitution in 1/|r1 −−−− r2|above yields:

z

y

x

rp re

|re − rp | e

Z eO

68](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-hydrogen-130507131157-phpapp01/85/Part-V-The-Hydrogen-Atom-68-320.jpg)

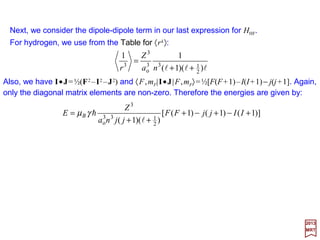

![In such tables we find (e.g., with s=a+b+c and X=a(a+1)−b(b+1)−c(c+1)):

2017

MRT

where X=I(I+1)+ j( j+1)−F(F+1).

2/1

)]32)(22)(12(2)12)(32)(22)(12(2)12[(

)]1()1(4)1(3[2

)1(

2 +++−+++−

++−+

−=

cccccbbbbb

ccbbXX

bc

cba s

Themainproblemthen is to evaluatethe reduced matrix elements 〈I||Q(2)||I 〉〈 j ||U(2) || j〉.

These 6j-symbols are invariant under:

1) an interchange of columns and;

2) an interchange of any two numbers in the bottom row with the corresponding two

numbers in the top row.

)32)(22)(12(2)12)(32)(22)(12(2)12(

)]1()1(4)1(3[2

)1(

2 +++−+++−

++−−

−=

++

jjjjjIIIII

jjIIXX

Ij

FjI jIF

So, by just interchanging the first and third columns, we find ours:

71](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-hydrogen-130507131157-phpapp01/85/Part-V-The-Hydrogen-Atom-71-320.jpg)

![The computation of 〈 j ||U(2) || j 〉 proceeds in analogous fashion. This time we define a

quantity eQ/2 as:

2017

MRT

where, from (i.e., for l=2) U(2) =−e√(4π/2⋅2+1)Ye

(2) /re

2+1, we get:

−

−=−= 5

e

2

e

2

e

3

e

ee

0

2

)2( 3

2

11

),(

5

π4

r

rz

e

r

YeUO ϕθ

We note that ∂2(−e/r)/∂z2 =−e(3z2 −r2)/r5 is the zz (diadic) component of the electric field

gradient tensor produced by an electron at a point whose coordinated with respect to the

electron are [x,y,z]. Since the origin of the coordinate system (see previous Figure) has

been positioned at the nucleus 2UO

(2) in the equation above is the zz component of the

electric field gradient tensor at the nucleus produced by an electron at re, or UO

(2) =

½(∂2V/∂z2)O =½Vzz where V is the potential due to the electron and the second derivative

is evaluated at the origin O (i.e.,at nucleus).We then have eq=〈 j,mj =j|Vzz | j,mj =j〉=〈Vzz〉

which is the average (or expectation value) of Vzz taken over the electronic state | j, j〉.

jmjUjmjQe jOj === ,,

2

1 )2(

qe

jj

jjjj

jj

)12(

)32)(32)(1)(12(

2

1)2(

−

++++

=U

Again, the use of the Wigner-Eckart theorem leads to the result:

73](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-hydrogen-130507131157-phpapp01/85/Part-V-The-Hydrogen-Atom-73-320.jpg)

![Now (without proof – c.f. M. Weissbluth) assuming axial symmetry, Vxx =Vyy, we have:

2017

MRT

where Vzz =eq. For this case there are only diagonal elements with twofold degenerates

in mI, that is, states with ±mI have the same energy.

)]1(3[

)12(4

,,

)]3([

)12(4

2

2

QQ

22

Q

+−

−

==

−

−

=

IIm

II

qQe

mIHmIE

IIV

II

eQ

H

III

zzz

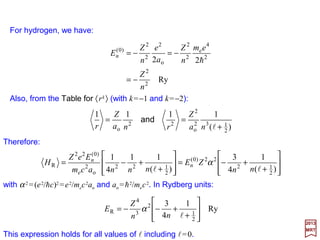

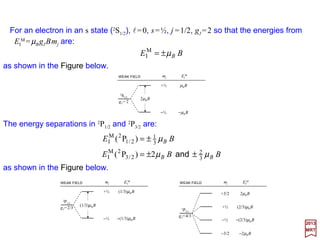

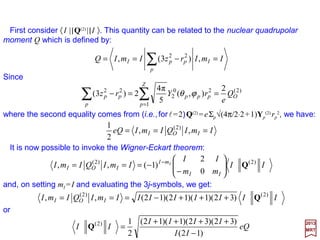

i. When I=1, the energies are:

( )

( )

=−

±=+

=−=+−

−

=

0

2

1

1

4

1

)23(

4

1

)]11(13[

)11.2(1.4 2

2

222

2

Q

I

I

II

mqQe

mqQe

mqQem

qQe

E

I = 1

mI EQ

(1/4)e2qQ±1

0 −(1/2)e2qQ

and the Figure below shows the quadrupole splitting (when I=1 and e2 qQ>0).

As has already been noted, the quadrupole interaction vanishes when I=0 or ½.

75](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-hydrogen-130507131157-phpapp01/85/Part-V-The-Hydrogen-Atom-75-320.jpg)

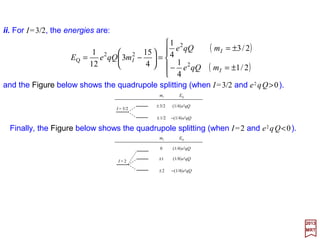

![ii. For I=3/2, the energies are:

2017

MRT

( )

( )

±=−

±=+

=

−=+−

−

=

2/1

4

1

2/3

4

1

4

15

3

12

1

)]12/3(2/33[

)12/3.2(2/3.4 2

2

222

2

Q

I

I

II

mqQe

mqQe

mqQem

qQe

E

and the Figure below shows the quadrupole splitting (when I=3/2 and e2 qQ>0).

and the Figure below shows the quadrupole splitting (when I=2 and e2 qQ<0).

I = 3/2

mI EQ

(1/4)e2qQ±3/2

−(1/4)e2qQ±1/2

I = 2

mI EQ

−(1/8)e2qQ±1

−(1/4)e2qQ0

(1/4)e2qQ±2

iii. Finally, for I=2, the energies are:

( )

( )

( )

=−

±=−

±=+

=−=+−

−

=

0

4

1

1

8

1

2

4

1

)63(

24

1

)]12(23[

)12.2(2.4

2

2

2

222

2

Q

I

I

I

II

mqQe

mqQe

mqQe

mqQem

qQe

E

76](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-hydrogen-130507131157-phpapp01/85/Part-V-The-Hydrogen-Atom-76-320.jpg)

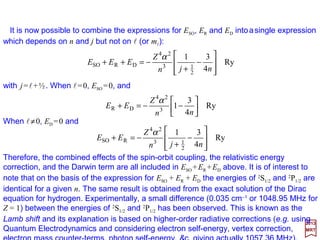

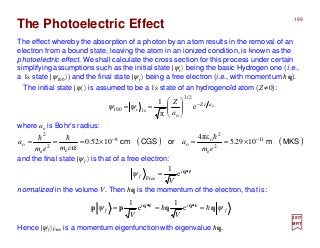

![This is the energy associated with the scalar potential energy, ϕ (105 cm−1).

And the significance of the various terms and their energies, is indicated to within an

order of magnitude (N.B., the ‘cm−1’ scale is given by the wave number 1/λ ≅ 8000 cm−1):

This contains the kinetic energy (i.e., p2 /2me) and interaction term (i.e., (e/2mec)(p • A+ A • p)

+ e2A2/2mec2) with a field represented by a potential vector A (105 cm−1). The interaction terms

are responsible or contribute to numerous physical processes among which are absorption,

emission and scattering of electromagnetic waves, diamagnetism, and the Zeeman effect.

2017

MRT

ϕe

The spin-orbit interaction (10-103 cm−1). More precisely, itis (eh/8mec2){σσσσ •[p −−−− (e/c)A]×××× E −−−−

σσσσ • E ×××× [p −−−− (e/c)A]} and it arises from the fact that the motion of the magnetic moment gives

rise to an electric moment for the particle which then interacts with the electric field.

This term appears in the expression of the relativistic energy:

and is therefore a relativistic correction to the kinetic energy (i.e., p2/2me) (0.1 cm−1).

The interaction of the spin magnetic moment (i.e., µS = 2⋅e/2me⋅h/2) with a magnetic field B=

∇∇∇∇ ×××× A (1 cm−1). Thus, it is the magnetic moment of one Bohr magneton, eh/2mec

(i.e., µB = 9.2741×10−24 A⋅m2 or J/T) with the magnetic field.

2

e2

1

+ Ap

c

e

m

A××××∇∇∇∇σσσσ •

cm

e

e2

h

23

e

4

8 cm

p

L+−+≅+ 23

ee

2

2

e

2222

e

82

)(

cm

p

m

p

cmcpcm

4

ϕ∇∇∇∇∇∇∇∇ •− 22

e

2

8 cm

eh

This term produces an energy shift in s-states and is known as the Darwin (1887-1962) term

(< 0.1 cm−1). It is thus a correction to the direct point charge interaction due to the fact that in the

representation (Foldy-Wouthuysen), the particle is not concentrated at a point but is spread out

over a volume with radius whose magnitude is roughly that of a Compton wavelength, h/mec.

p××××∇∇∇∇σσσσ ϕ•− 22

e4 cm

eh

ϕe

c

e

m

−

+

2

e2

1

Ap

As a combination, this term represents the interaction of a point charge with the

electromagnetic field.

78](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-hydrogen-130507131157-phpapp01/85/Part-V-The-Hydrogen-Atom-78-320.jpg)

![Eigenfunctions of the wave equation having different energy eigenvalues are

necessarily orthogonal, as we will now show. Let ψi and ψj be solutions of:

2017

MRT

If the integration is extended over all space, we obtain:

0)(

2 *

2

2

*2

2

*2

2

*2

2

2

2

2

2

2

*

=−+

∂

∂

+

∂

∂

+

∂

∂

−

∂

∂

+

∂

∂

+

∂

∂

∫ ∫ ∫

∫ ∫ ∫

∞

∞−

∞

∞−

∞

∞−

∞

∞−

∞

∞−

∞

∞−

zdydxdEE

m

zdydxd

zyxzyx

ijji

i

jjjiii

j

ψψ

ψ

ψψψψψψ

ψ

h

82

0)(

2

0)(

2 *

2

*2

2

2

=−+∇=−+∇ jjjiii VE

m

VE

m

ψψψψ

hh

and

Multiplying the terms in the first equation by ψ j

* and the terms in the second by ψi on the

right, and subtracting the second equation from the first, we obtain;

0)(

2

)( *

2

*22*

=−+∇−∇ ijjiijij EE

m

ψψψψψψ

h

or integrating over the particle coordinates after representing the system in Cartesian

coordinates, we obtain:

0)(

2

])([ *

2

*22*

=−+∇−∇ ∫∫ τψψτψψψψ dEE

m

d ijjiijij

h](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-hydrogen-130507131157-phpapp01/85/Part-V-The-Hydrogen-Atom-82-320.jpg)

![Substituting V =V 0 +V ′, Ei =E0

i +E′i and ψi =ψ 0

i +ψ ′i into the Schrödinger equation

above and grouping the result in ascending order of approximation, we have:

2017

MRT

This first term is zero by comparing to the unperturbed Schrödinger equation, leaving us

with only the second term for a first-order approximation:

0])(-)()[()( 000000

=′′−′+′−+′−+− iiiiiiii EVEVEHEH ψψψψ assuchtermsordersecond

85

0)()( 000

=′−′+′− iiii EVEH ψψ

We now expand ψ ′i in terms of the complete orthonormal set of solutions to the

unperturbed Schrödinger equation, ψ 0

j. That is, we let:

∑

∞

=

=′

0

0

j

jjii a ψψ

which, with first-order approximation above, gives:

0)()( 0000

=′−′+−∑ ii

j

jjii EVaEH ψψ

Note that from H0ψ 0

i =E0

iψ 0

i, this last equation can be rewritten:

0)()( 0000

=′−′+−∑ ii

j

jjiij EVaEE ψψ

Multiplying this last equation by ψ 0

k

* on the left and integrating over all space, we get:

0)( 0*00*00*000

=′−′+− ∫∫∑ ∫ τψψτψψτψψ dEdVdaEE ikiik

j

jkjiij](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-hydrogen-130507131157-phpapp01/85/Part-V-The-Hydrogen-Atom-85-320.jpg)

![The integrand in the last monster integral is essentially the electrostatic interaction

energy between two shells of charge density exp(−ρ1) and exp(−ρ2). To begin evaluating

it let us consider just the integral over ρ1. Let us consider further the potential at a point ρ

due to a shell of thickness dρ1 at ρ1; it is given by:

2017

MRT

and

)(eπ4

e

π4 111

1

12

1

1

1

ρρρρ

ρ

ρ

ρ ρ

ρ

<= −

−

ford

d

90

)(e

π4e

π4 11

2

1

12

1

1

1

ρρρρ

ρρ

ρ

ρ ρ

ρ

>= −

−

ford

d

)]2(e2[

π4

e

π4

eπ4)( 1

2

111

11

+−=+= −

∞

−

∞

−

∫∫ ρ

ρ

ρρ

ρ

ρρρφ ρ

ρ

ρ

ρ

ρ

dd

The total potential at ρ due to the infinite sphere of charge density exp(−ρ1) is given by:

This is the potential at a point ρ due to the entire distribution of charge density exp(−ρ1).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-hydrogen-130507131157-phpapp01/85/Part-V-The-Hydrogen-Atom-90-320.jpg)

![We can now evaluate the potential energy of interaction between the distribution of

charge density exp(−ρ1) and exp(−ρ2). The potential energy per unit volume of a charge

density exp(−ρ2) at a point ρ2 is given by (4πρ2)[2−(ρ2 +2)exp(−ρ2)]exp(−ρ2). Hence, the

second shell of charge 4πρ2

2exp(−ρ2)dρ2 has a potential energy of:

2017

MRT

91

])2(e2[

eπ)4(

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

+−

−

−

ρ

ρ

ρρ ρ

ρ

d

The total electrostatic potential of the sphere of charge density exp(−ρ2) due to the

sphere with charge density exp(−ρ1) is the integral over ρ2 of this last expression:

2

0

222

2

π)4(

4

5

])2(e2[eπ)4( 22

=+−∫

∞

−−

ρρρ ρρ

d

Therefore our monster integral yields a result of:

2

4

e

0

2

1

24

5

24

5

h

eZm

a

eZ

E ==′

and from Ei =−(meZ2e4/2h2)(1/n1

2 +1/n2

2)+ ∫ψ 1

0*

(1,0)ψ 2

0*

(1,0)(e2/r12)ψ 1

0

(1,0)ψ 2

0

(1,0)dτ above:

−−= ZZ

em

E

4

5

2

2

2

2

4

e

1

h

where mee4/2h2 is the ground state energy of the Hydrogen atom and 2Z 2 times this is

the unperturbed ground state energy of the two Helium electrons.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-hydrogen-130507131157-phpapp01/85/Part-V-The-Hydrogen-Atom-91-320.jpg)

![Consider a system of two identical particles such that one particle is in a state labeled

α and the other in another state labelled by β where α(1) represents particle 1 in state α,

&c. If particles 1 and 2 are interchangeable in either the α(1)α(2) or β(1)β(2) state, then

eigenfunction is unchanged and therefore these states are said to be symmetric. The

other states α(1)β(2) and β(1)α(2) are neither entirely symmetric nor entirely

antisymmetric, however, and it is convenient to treat them as a superposition of two

other states one of which is entirely symmetric and the other antisymmetric. We

therefore use linear combinations of the α(1)β(2) and β(1)α(2) states to represent the

two remaining wave functions of the system:

2017

MRT

where the factor 1/√2 is used for normalization. Since the α(1), β(2), α(2), and β(1) are

all solutions of the Schrödinger equation, the ψS and ψA will also be solutions. Now, in

our universe, systems of identical particles with integer spin must be represented by

wave functions which are symmetric with respect to the exchange of any two particles.

Similarly, all systems of identical particles with half-integer spin must be represented by

wave functions which are antisymmetric after exchange of any two particles. For multi-

electron system, this result was first postulated by W. Pauli in 1924 even before the

advent of quantum mechanics. The Pauli exclusion principle states that in a multi-elec-

tron atom there can never be more than one electron in the same quantum state. This

statement can be seen to be a consequence of saying that the electron wave function

must be antisymmetric since electrons belong to the half-integer class of particles.

)]2()1()2()1([

2

1

)]2()1()2()1([

2

1

αββαψαββαψ −=+= AS or

94](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-hydrogen-130507131157-phpapp01/85/Part-V-The-Hydrogen-Atom-94-320.jpg)

![Towards the end of the The Hydrogen Atom chapter we saw that the wave function for

an electron with spin could be written as follows:

2017

MRT

so that for the Helium atom with two electrons we will have to take the appropriate

combination of the two wave functions ψa(1)=ψa(1)ξξξξa and ψb(2)=ψb(2)ξξξξb, where ψa(1)

represents the first electron at position 1 with a spin z-component represented by ξξξξa (i.e.,

either +½h or −½h) and similarly for ψb(2). The total wave function for the two electrons

will have to be the appropriate combination of space and spin states that makes it

antisymmetric. This total wave function can of course be written as the product of a

space part times a spin part; if the space part is symmetric, the spin part must be

antisymmetric and vice versa. As we have seen, the space part can be written:

95

smmn ξξ llψψψ == SpinSpace

_ _ _

_

)]1()2()2()1([

2

1

)]1()2()2()1([

2

1

babaAbabaS ψψψψψψψψψψ −=+= or](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-hydrogen-130507131157-phpapp01/85/Part-V-The-Hydrogen-Atom-95-320.jpg)

![The spin wave function will be a bit more complicated because the separate spin

angular momenta can add vectorially just as the orbital and spin angular momenta do in

the case of the two-electron atom. Instead of having J=L+S, here S=s1 ++++s2 so that S=0

or 1. The magnitude of S will of course be √[S(S+1)]h.

2017

MRT

For S=0, ms =0 and we have just a single state while for S=1, ms =+1, 0, −1 and a triplet

spin state results. This corresponds to the three possible orientations with respect to

some preferred (i.e., z) direction in space and is equivalent to saying that we can start

with the following four spin combinations: ξξξξa(½)ξξξξb(½), ξξξξa(−½)ξξξξb(−½), ξξξξa(½)ξξξξb(−½), and

ξξξξa(−½)ξξξξb(½) to construct four symmetric and antisymmetric combinations:

tripletsymmetric

singletricantisymmet

-

)½()½(

)]½()½()½()½([

2

1

)½()½(

1

0

1

1

1

1

-)]½()½()½()½([

2

1

00

−−

−+−

−

+

−−−

ba

baba

ba

baba

smS

ξξ

ξξξξ

ξξ

ξξξξ

96](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-hydrogen-130507131157-phpapp01/85/Part-V-The-Hydrogen-Atom-96-320.jpg)

![The total eigenfunction must be antisymmetric and thus we can form the following

combination from ψS , ψA and the above four spin combinations:

2017

MRT

and

97

]-[]-[ tripletsymmetricandsingletricantisymmet ⊗⊗ AS ψψ

or:

)]½()½()½()½([)]1()2()2()1([

2

1

babababa ξξξξ −−−⊗+ ψψψψ

−−

−+−⊗−

)½()½(

)]½()½()½()½([

2

1

)½()½(

)]1()2()2()1([

2

1

ba

baba

ba

baba

ξξ

ξξξξ

ξξ

ψψψψ

Notice that if the spin part of the wave function is symmetric, corresponding to parallel

spins, the space part must be antisymmetric. This has the interesting and important

consequence that the electrons will have small probability of being found close together

if they have parallel spins and a maximum probability of being found close together if

they have antiparallel spins. One can say that in effect parallel spins repel and

antiparallel spins attract.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-hydrogen-130507131157-phpapp01/85/Part-V-The-Hydrogen-Atom-97-320.jpg)

![By use of these matrix elements between the various hydrogen-like wave functions,

the secular determinant is written as:

2017

MRT

since all the Js and Ks with the same subscript are equal.

0

)(000000

)(000000

00)(0000

00)(0000

0000)(00

0000)(00

000000)(

000000)(

pp

pp

pp

pp

pp

pp

ss

ss

=

∆−

∆−

∆−

∆−

∆−

∆−

∆−

∆−

EJK

KEJ

EJK

KEJ

EJK

KEJ

EJK

KEJ

105

where ∆E is the small energy shift due to the perturbation. This determinant can be

rewritten as:

0])][()[( 32

p

2

p

2

s

2

s =−−∆−−∆ KJEKJE](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-hydrogen-130507131157-phpapp01/85/Part-V-The-Hydrogen-Atom-105-320.jpg)

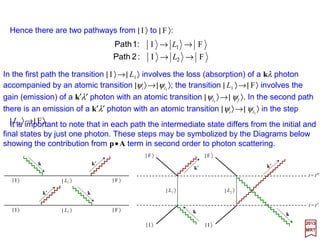

![x

y

x

y

r

ψ0

S

ψ0

A

ψ0

S

ψ0

A

r

When r is large the electron can be thought of as belonging to one proton or the other,

but as r becomes small this distinction is not possible and we must consider the effects

of exchange degeneracy. In this case, we ought then to take the total wave function as

being either symmetric or antisymmetric. For convenience we take both protons to be

lying on the x-axis so that under an exchange it is only the x coordinate that varies. Then

we write:

2017

MRT

Further, for the ground state U100 we choose the x-axis so that we have U100(x,0,0). Both

ψ0

S and ψ0

A are shown in the Figure for different values of r. Looking at these plots, we

see that as r→0 (at x=0), ψ0

S →maximum and ψ0

A →0.

)],,(),,([

2

1

)],,(),,([

2

1

2121 zyxUzyxUzyxUzyxU nn

A

nnn

S

n −=+= ψψ or

120

Illustrating the form of the symmetric and antisymmetric wave functions of the H2

++++ molecule for two

different proton separation distances (Left vs Right) .](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-hydrogen-130507131157-phpapp01/85/Part-V-The-Hydrogen-Atom-120-320.jpg)

![Then the degenerate perturbation integrals are:

2017

MRT

and

∫∫ ′= 212B1A2

*

B1

*

A )()()()( ττψψψψ ddHJ rrrr

127

where dτ1 and dτ2 are the differential spherical volume elements (e.g., dτ1 =

r1

2sinθ1dr1dθ1dϕ1). The second term in the exchange integral K with H0, which we will

label K0, must be included because our initial wave functions are not orthonormal. Since:

∫∫∫∫ +′= 211B2A

0

2

*

B1

*

A211B2A2

*

B1

*

A )()()()()()()()( ττψψψψττψψψψ ddHddHK rrrrrrrr

)()(2)()()()( 1B2A11B2A

0

1B2A

0

rrrrrr ψψψψψψ EEH ==

we have:

∫∫= 211B2A2

*

B1

*

A10 )()()()(2 ττψψψψ ddEK rrrr

The contribution of e2/rAB term to J is simply e2/rAB, since the wave functions are

normalized and e2/rAB may be taken outside the integration over the electron

coordinates. Similarly, the contribution of the e2/rAB term to K is simply [(e2/rAB)/2E1]K0.

The contribution of e2/r1B to J would be ∫ψA

*(r1)(−e2/r1B)ψA(r1)dτ1 since ψB(r2) is

normalized and r1B is not a function of the position of the second electron. The

contribution of e2/r1B to K would be similar.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-hydrogen-130507131157-phpapp01/85/Part-V-The-Hydrogen-Atom-127-320.jpg)

![It is found that the symmetric wave function:

2017

MRT

is the correct zero-order wave function which with its antisymmetric twin causes the

perturbation matrix to be diagonal. The wave function above is also the symmetric wave

function whose eigenvalue is approximately E0 −K, the lower of the two energy

eigenvalues including resonances. This is in contrast to the case of Helium where both

electrons are in the same atom, and the antisymmetric wave function was found to be

the lower of the two energy eigenvalues including resonances. The attractive bonding

force of the Hydrogen molecule has been shown to be due to the possibility of two

electrons being in a symmetric state (i.e., being interchangeable in the space wave

function representation). Since no more than two electrons can be in one symmetric

state at the same time, the degeneracy in this case can be only twofold.

)]()()()([

2

1

1B2A2B1A

1

0

rrrr ψψψψψ +

+

=

E

K

S

129](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-hydrogen-130507131157-phpapp01/85/Part-V-The-Hydrogen-Atom-129-320.jpg)

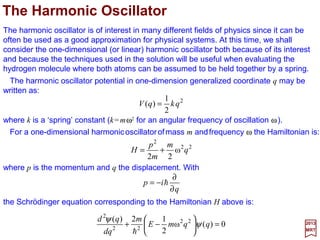

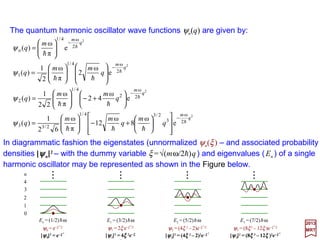

![The eigenfunctions of the harmonic oscillator version of the Schrödinger equation:

in which Hn(x) is a Hermit polynomial* of degree n and the eigenvalues are:

2017

MRT

A more convenient form to the ψn(q) solution above is achieved by changing the

variables to:

We then have:

which has the properties:

nn

m

uq

m

q ψξ

ω

ω

)(

h

h

== and

)()1()(

22

1

1

2

1

2

1

11

11

ξξξ

ξ

ξ

ξ

ξδξ

n

n

nnnn

nnnnnmnm

uuu

n

u

n

u

unu

d

d

unu

d

d

duu

−=−+

+

=

+=

−=

+=

−+

+−

∞+

∞−∫

and

,,,

=

−

q

m

H

m

n

q n

q

m

nn

hh

h ω

e

π

ω

!2

1

)(

2

2

ω4/1

2/

ψ

( ),...,,nnEn 210ω)½()ω( =+= h

* The Hermit polynomials are solutions to the differential equation d2Hn/dx2 – 2xdHn/dx − 2nHn = 0 and have a solution of the form

Hn(x) = (−1)n exp(x2)dn[exp(−x2)]/dxn. The first four Hermit polynomials are H0(x) = 1, H1(x) = 2x, H2(x) = −2 + 4x2 and H3(x)= −12x + 8x3.

)(e

)!2π(

1

)( 2

2/12/

2

ξξ ξ

nnn H

n

u −

=

142](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-hydrogen-130507131157-phpapp01/85/Part-V-The-Hydrogen-Atom-142-320.jpg)

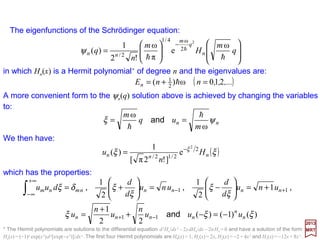

![We shall now investigate the harmonic oscillator be means of a matrix formulation. For

convenience, let:

so that the Hamiltonian H=p2/2m+½mω2q2 becomes

2017

MRT

The transition to quantum mechanics is made by reinterpreting P and Q as Hermitian

operators which obey the commutation relation:

which is equivalent to the replacement of P by −ih∂/∂Q. It is important to note that the

quantum mechanical operators Q and P are independent of time.

We now construct the linear combinations:

hiQPQPPQ =≡− ],[

)ω(

ω2

1

)ω(

ω2

1 †

PiQaPiQa −=+=

hh

and

22

2

2

)()( qmqQ

m

p

pP == and

)ω(

2

1 222

QPH +=

or:

)(

2

ω

)(

ω2

††

aaiPaaQ −=+=

hh

and

143](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-hydrogen-130507131157-phpapp01/85/Part-V-The-Hydrogen-Atom-143-320.jpg)

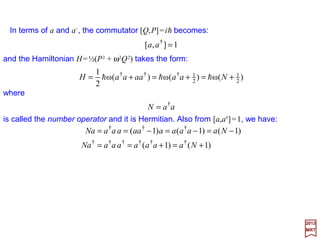

![In terms of a and a†, the commutator [Q,P]=ih becomes:

and the Hamiltonian H=½(P2 + ω2Q2) takes the form:

where:

2017

MRT

is called the number operator and it is Hermitian. Also from [a,a†]=1, we have:

)1()1()1( †††

−=−=−== NaaaaaaaaaaNa

1],[ †

=aa

+=

+=+=

2

1

ω

2

1

ω)(ω

2

1 †††

NaaaaaaH hhh

aaN †

=

144

)1()1( ††††††

+=+== NaaaaaaaNa

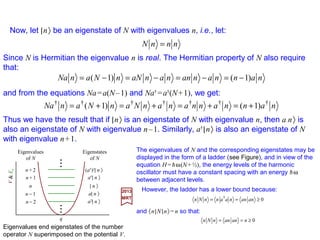

and:](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-hydrogen-130507131157-phpapp01/85/Part-V-The-Hydrogen-Atom-144-320.jpg)

![We now express the vector potential A(r,t) as a linear superposition of plane waves:

2017

MRT

∑∑

∑∑

=

−•−−•

−•−−•−•−−•

+=

+++=

k

rkrk

k

rkrk

k

rkrk

kk

kkkk

kkke

kkkekkkerA

2,1

)ω(*)ω(

)ω(*

2

)ω(

22

)ω(*

1

)ω(

11

]e)(e)()[(ˆ

]e)(e)()[(ˆ]e)(e)()[(ˆ),(

r

ti

r

ti

rr

titititi

AA

AAAAt

where êr(k) is a real unit vector which indicates the linear polarization; êr(k) depends on

the propagation direction k and has two independent components ê1(k) and ê2(k) which

satisfy êr(k)•ês(k) =δrs (r,s=1,2). Ar(k) is a constant amplitude for the mode (k,r).

The Coulomb gauge ∇∇∇∇•A=0 ensures the transversality of the electromagnetic fields

so that êr(k)•k=0. Thus ê1(k), ê2(k), and k form a right-handed set of mutually orthogonal

unit vectors.

ˆ ˆ

The vector potential A(r,t) above then consists of plane wave each one labeled by the

propagation vector k and the real polarization vector êr(k). Furthermore, A(r,t) is real.

We may also replace the linear polarization vectors ê1(k) and ê2(k) by unit vectors

which indicate circular polarizations. This is accomplished by defining ê+(k)=−(1/√2)[ê1(k)

++++iê2(k)] and ê−(k)=(1/√2)[ê1(k)−−−−iê2(k)]. These vectors satisfy êr(k) ××××ês(k)=iδrs (r,s=±1).

With r=+1 the cross product gives a vector parallel to the direction of propagation

whereas with r=−1 the cross product is antiparallel. For this reason one refers to ê+(k)

and ê−(k) as positive and negative helicity (unit) vectors. ê+(k) and ê−(k) represent left

and right circular polarization, respectively.

152](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-hydrogen-130507131157-phpapp01/85/Part-V-The-Hydrogen-Atom-152-320.jpg)

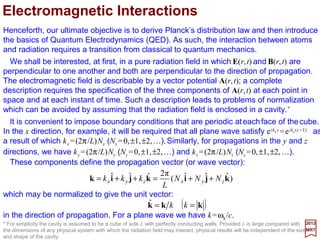

![The electric and magnetic fields are obtained directly from the vector potential.

For the electric field:

For the magnetic field, since it is defined by B(r,t)=∇∇∇∇××××A(r,t), it is necessary to

evaluate ∇∇∇∇××××A. Noting that ∇∇∇∇××××(ϕA)=∇∇∇∇ϕ ××××A++++ϕ∇∇∇∇××××A we have:

2017

MRT

Since both the amplitude Ar(k) and the polarization vector êr(k) are constant the second

term vanishes and we get:

Hence the magnetic field is:

∑∑ −•−−•

−=

∂

∂

−=

k

rkrk

k

kk

kkke

rA

rE

r

ti

r

ti

rr AA

c

i

t

t

c

t ])e()e([)(ˆω

),(1

),( )ω(*)ω(

)(ˆ)e()(ˆe)()(ˆ)e( kekkekkek rkrkrk

r

i

rr

i

rr

i

r AAA ××××∇∇∇∇××××∇∇∇∇××××∇∇∇∇ •••

+=

)(ˆˆ)e(

ω

)(ˆe)()(ˆ)e( kekkkekkek rkkrkrk

r

i

rr

i

rr

i

r A

c

iAA ××××××××∇∇∇∇××××∇∇∇∇ •••

+==

∑∑ −•−−•

−==

k

rkrk

k

kk

kkkekrArB

r

ti

r

ti

rr AA

c

i

tt ])e()e(][)(ˆˆ[ω),(),( )ω(*)ω(

××××××××∇∇∇∇

153](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-hydrogen-130507131157-phpapp01/85/Part-V-The-Hydrogen-Atom-153-320.jpg)

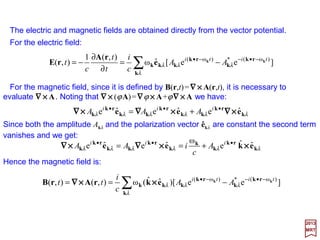

![To obtain the Hamiltonian for the electromagnetic field in the cavity it is necessary to

express the field energy W in terms of canonical variable.

From electromagnetic theory:

where V is the volume of the cavity and the fields E and B are given by the expressions

derived earlier. Because of the boundary conditions of the type exp(ikx x)=exp[ikx (x+L)],

we get:

2017

MRT

Therefore:

If we write:

( )

( )

=

≠

=∫

•±

0

00

e

k

krk

for

for

V

dV

V

i

ti

rr AtA k

kk ω

e)(),( −

=

∫∫ +=•+•=

VV

dVdVW )(

π8

1

)(

π8

1 22

BEBBEE

VdVVdV

V

i

V

i

kk

rkk

kk

rkk

′

•′−±

−′

•′+±

== ∫∫ δδ )()(

ee and

in our previous expression for E(r,t) and use the orthogonality condition êr(k)•ês(k)=δrs

on the polarization vectors and the relation ωk =ω−k, we get:

∑∑∑∑∑∫ −+−−•−=•

k

k

k

k kkkkkekekkEE

r s

srsr

r

rr

V

tAtAtAtA

c

V

tAtA

c

V

dV )],(),(),(),()][(ˆ)(ˆ[ω),(),(ω

2 **2

2

*2

2

154](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-hydrogen-130507131157-phpapp01/85/Part-V-The-Hydrogen-Atom-154-320.jpg)

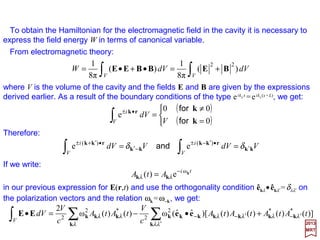

![To compute the field energy associated with B we employ the vector identity

(A××××B)•(C××××D)=(A•C)(B•D)−(A•D)(B•C) to show that [k××××êr(k)]•[−k××××ês(k)]=δrs in

which the orthogonality property êr(k)•k=0 has been used. We also have

[k××××êr(k)]•[−k××××ês(k)]=−êr(k)•ês(−k).

2017

MRT

Actually, W is dependent of time because of the exponential time dependence of Ar(k,t)

as given previously. Hence:

It is observed that the total energy is merely the sum of the energies in the individual

modes as a consequence of the orthogonality conditions ∫V exp(±i(k+k′)•r)dV =δk′−kV

and ∫V exp(±i(k−k′)•r)dV =δk′kV; furthermore the energy is shared equally by the electric

and magnetic fields.

∑∑=

k

k kk

r

rr tAtA

c

V

W ),(),(ω

π2

*2

2

ˆ

ˆ ˆ

Therefore in computing the integral of B•B using the expression B(r,t) derived

previously one finds two terms identical to the two terms on the right side of the

∫V E•EdV except for the sign of the second term. The field energy then becomes:

ˆ ˆ

∑∑=

k

k kk

r

rr AA

c

V

W )()(ω

π2

*2

2

155](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-hydrogen-130507131157-phpapp01/85/Part-V-The-Hydrogen-Atom-155-320.jpg)

![We now introduce a new set of variables:

which when substituted into our previous expression for W, gives:

2017

MRT

)]()(ω[

π

ω

)()]()(ω[

π

ω

)( *

kkkkkk k

k

k

k

rrrrrr PiQ

V

c

APiQ

V

c

A −=+= and

∑∑ +=

k

k kk

r

rr QPW )](ω)([

2

1 222

Upon inverting the Qr(k) and Pr(k) variables above, we get:

)]()([

2

ω

π

)()]()([

2

1

π

)( **

kkkkkk k

rrrrrr AA

c

V

iPAA

c

V

Q −−=+= and

Finally, it is noted that the Hamiltonian W=½ΣkΣr[Pr

2(k)+ωk

2Qr

2(k)] is precisely of the

same form as that for an assembly of simple harmonic oscillators whose Hamiltonians

are given by H=½(P2 +ω2Q2).

Each mode of radiation field is therefore formally equivalent to a single harmonic

oscillator when we let P2 =p2/m and Q2 =mq2 so that the Hamiltonian H=p2/2m+(m/2)ω2q2

became:

)ω(

2

1 222

QPH +=

156](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-hydrogen-130507131157-phpapp01/85/Part-V-The-Hydrogen-Atom-156-320.jpg)

and a† =[1/√(2hω)](ωQ−iP)) we define:

which then must obey, the commutation rules:

In term of these operators the Hamiltonian W=½Σkr[Pr

2(k)+ωk

2Qr

2(k)] becomes:

0])(,)([])(,)([])(,)([ =′=′=′ ′ kkkkkk kk srsrsrsr PPQQiPQ andδδh

Quantization of the Radiation Field

])()(ω[

ω2

1

)(])()(ω[

ω2

1

)( †

kkkkkk k

k

k

k

rrrrrr PiQaPiQa −=+=

hh

and

0)](),([)](),([)](),([ ††

=′=′=′ ′ kkkkkk kk srsrsrsr aaaaaa andδδ

∑∑∑∑∑∑

+=

+==

k

k

k

k

k

kkkk

r

r

r

rr

r

r NaaHH

2

1

)(ω

2

1

)()(ω)( †

hh

in which Nr(k) is known as the number operator for the mode k and polarization r and is

given by:

)()()( †

kkk rrr aaN =

157](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-hydrogen-130507131157-phpapp01/85/Part-V-The-Hydrogen-Atom-157-320.jpg)

![A complete description of the radiation field consists of an enumeration of the

occupation numbers nr(k). Since each mode is independent of the product of all

eigenstates, |nr(k)〉 is an eigenstate of the total field. A many-photon state is therefore

described by:

The notation is becoming quite cumbersome; we shall therefore make the replacement

nri

(ki) =ni so that the many-photon state is written as:

2017

MRT

With the orthogonality requirement:

for operators, we also replace the indices ri by the index i. The many-photon analog of

ar(k)|nr(k)〉=√ nr(k)|nr(k)−1〉, a†

r(k)|nr(k)〉=√[nr(k)+1]|nr(k)+1〉 and ar(k)|0〉=0 is:

with:

LLLL ),(,),(),()()()( 2121 2121 irrrirrr ii

nnnnnn kkkkkk =

∑

+=

i

ii nE

2

1

ωh

( ))(,,,, 21 irii i

nnnnn k≡LL

LLLLLL ii nnnnnnii nnnnnn ′′′=′′′ δδδ 2211

,,,,,,,, 2121

as well as ai|n1,n1,…,0,…〉=0, and the analog of Nr(k)|nr(k) 〉=nr(k) |nr(k)〉 is:

LLLL ,,,,,,,, 2121 iiii nnnnnnnN =

LLLLLLLL ,1,,,1,,,,,1,,,,,,, 2121

†

2121 ++=−= iiiiiiii nnnnnnnannnnnnna &

160](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-hydrogen-130507131157-phpapp01/85/Part-V-The-Hydrogen-Atom-160-320.jpg)

![When nr(k)=0, there are no photons in the mode (k,r); nevertheless the energy in the

mode, according to E=ΣkΣr Er(k) =ΣkΣr hωk[nr(k)+½], is ½hωk. This value, which is

characteristic of the harmonic oscillator, is known as the zero point energy.

2017

MRT

Since observables associated with non-commutating operators are subject to the

uncertainty principle, an increase in precision in the number of photons means an

increase in the uncertainty in the fields.

For the radiation field as a whole with an infinite number of modes, the zero point

energy becomes infinite. This is one of the particularities of the quantum-mechanical

description of the radiation field. A formal explanation is based on the non-commutativity

of the number operator Nr(k) with the annihilation and creation operators ar(k) and a†

r(k)

as a result of which ΣkΣrNr(k) does not commute with the fields E and B.

When no photons are present, the fluctuations in the field strengths are responsible for

the infinite zero point energy. Fortunately, a consistent description of physical processes

in practically all cases is obtained by simply ignoring the infinite zero point energy of the

radiation field.

161](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-hydrogen-130507131157-phpapp01/85/Part-V-The-Hydrogen-Atom-161-320.jpg)

![The transition from classical to quantum mechanics seen in [Qr(k),Ps(k′)]=ihδkk′δrs

and [Qr(k),Qs(k′)]=[Pr(k),Ps(k′)]=0 which implies that the classical vector potential

A(r,t)=ΣkΣr êr(k){Ar(k) exp[i(k•r−ωkt)]+Ar

* (k)exp[−i(k•r−ωkt)]} becomes a quantum-

mechanical operator.

2017

MRT

We now write the quantum-mechanical vector potential by substituting Ar(k) and Ar

*(k)

into A(r,t)=ΣkΣrêr(k){Ar(k) exp[i(k•r−ωkt)]+Ar

*(k)exp[−i(k•r−ωkt)]} and we get:

)(

ω

2π

)()(

ω

2π

)( †

2

*

2

kkkk

kk

rrrr a

V

c

Aa

V

c

A

hh

→→ and

∑∑ −•−−•

+=

k

rkrk

k

kk

kkkerA

r

ti

r

ti

rr aa

V

c

t ]e)(e)()[(ˆ

ω

2π

),( )ω(†)ω(

2

H

h

This transition may be accomplished by means of the transformations

Qr(k)=√(V/π)(1/2c)[Ar(k)+Ar

*(k)] and Pr(k)=−i√(V/π)(ωk/2c )[Ar(k)−Ar

*(k)] which relate

Ar(k) and Ar

*(k) to Qr(k) and Pr(k); the latter in turn are related to the annihilation and

creation operators ar(k) and ar

†(k), via ar(k)=[1/√(2hωk)][ωk Qr(k)+iPr(k)] and

ar

†(k)=[1/√(2hωk)][ωk Qr(k) −iPr(k)]. Hence the required replacement is:

which is spelled out in the Heisenberg representation. In the Schrödinger representation:

∑∑ •−•

+=

k

rkrk

k

kkkerA

r

i

r

i

rr aa

V

c

]e)(e)()[(ˆ

ω

2π

)( †

2

h

162](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-hydrogen-130507131157-phpapp01/85/Part-V-The-Hydrogen-Atom-162-320.jpg)

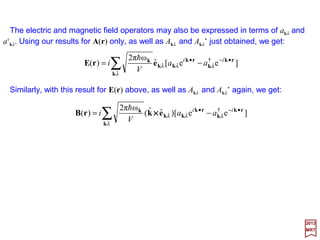

![The electric and magnetic field operators may also be expressed in terms of ar(k) and

ar

†(k). Using our results for A(r) only, as well as Ar(k) and Ar

*(k) just obtained, we get:

Similarly, with this result for E(r) above, as well as Ar(k) and Ar

*(k) again, we get:

2017

MRT

∑∑ •−•

−=

k

rkrkk

kkkerE

r

i

r

i

rr aa

V

i ]e)(e)()[(ˆ

ω2π

)( †h

∑∑ •−•

−=

k

rkrkk

kkkekrB

r

i

r

i

rr aa

V

i ]e)(e)()][(ˆˆ[

ω2π

)( †

××××

h

163](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-hydrogen-130507131157-phpapp01/85/Part-V-The-Hydrogen-Atom-163-320.jpg)

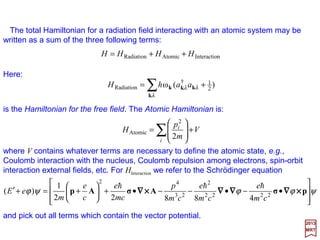

![The total Hamiltonian for a radiation field interacting with an atomic system may be

written as a sum of the three following terms:

Here:

2017

MRT

is the Hamiltonian for the free field. The Atomic Hamiltonian is:

where V contains whatever terms are necessary to define the atomic state, e.g.,

Coulomb interaction with the nucleus, Coulomb repulsion among electrons, spin-orbit

interaction external fields, etc. For HInteraction we refer to the Schrödinger equation

and pick out all terms which contain the vector potential.

nInteractioAtomicRadiation HHHH ++=

∑∑ +=

k

k kk

r

rr aahH ]½)()([ω †

Radiation

V

m

p

H

i

i

+

= ∑ 2

2

Atomic

ψϕϕψϕ

•−•−−•+

+=+′ pAAp ××××∇∇∇∇ΣΣΣΣ∇∇∇∇∇∇∇∇××××∇∇∇∇ΣΣΣΣ 2222

2

23

42

48822

1

)(

cm

e

cm

e

cm

p

mc

e

c

e

m

eE

hhh

164](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-hydrogen-130507131157-phpapp01/85/Part-V-The-Hydrogen-Atom-164-320.jpg)

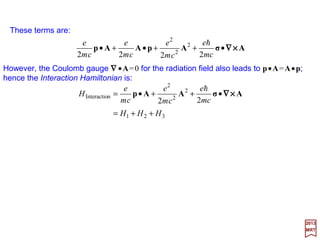

![The total Hamiltonian H=HRadiation +HAtomic +HInteraction may now be written as:

where:

∑∑∑∑ •−+•−

•=•=

k

rk

kk

rk

k

kpkekpke

r

i

rr

r

i

rr a

Vm

e

Ha

Vm

e

H e)(])(ˆ[

ω

2π

e)(])(ˆ[

ω

2π †)(

1

)(

1

hh

and

)(

1

)(

1

†

1 ]e)(e)(][)(ˆ[

ω

2π

+−

•−•

+=

+•= ∑∑

HH

aa

Vm

e

H

r

i

r

i

rr

k

rkrk

k

kkpke

h

With the use of the vector potential obtain A(r)=ΣkΣr êr (k){Ar (k)exp[i(k•r−ωkt)]+

Ar

*(k)exp[−i(k•r−ωkt)]} earlier:

in which H0 contains HRadiation and HAtomic and HInteraction is given by the expression derived

above.

We now assume that HInteraction can be regarded as a perturbation on H0 although, as in

previous cases, the justification is not apparent until the calculations have been

completed. We shall concentrate on the term, H1, of the perturbed Hamiltonian:

nInteractio0 HHH +=

Ap•=

cm

e

H1

which is most often the dominant term in electromagnetic interactions.

2017

MRT

166](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-hydrogen-130507131157-phpapp01/85/Part-V-The-Hydrogen-Atom-166-320.jpg)

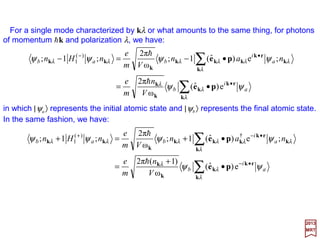

![For a single mode characterized by (k,r) or what amounts to the same thing, for

photons of momentum hk and polarization r, we have:

2017

MRT

in which |ψa〉 represents the initial atomic state and |ψb〉 represents the final atomic

state. In the same fashion, we have:

a

r

i

rb

r

ra

r

i

rrrbrarb

V

n

m

e

nan

Vm

e

nHn

ψψ

ψψψψ

∑∑

∑∑

•

•−

•=

•−=−

k

rk

k

k

rk

k

pke

k

kkpkekkk

e])(ˆ[

ω

)(2π

)(;e)(])(ˆ[1)(;

ω

2π

)(;1)(; )(

1

h

h

a

r

i

rb

r

ra

r

i

rrrbrarb

V

n

m

e

nan

Vm

e

nHn

ψψ

ψψψψ

∑∑

∑∑

•−

•−+

•

+

=

•+=+

k

rk

k

k

rk

k

pke

k

kkpkekkk

e])(ˆ[

ω

]1)([2π

)(;e)(])(ˆ[1)(;

ω

2π

)(;1)(; †)(

1

h

h

167](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-hydrogen-130507131157-phpapp01/85/Part-V-The-Hydrogen-Atom-167-320.jpg)

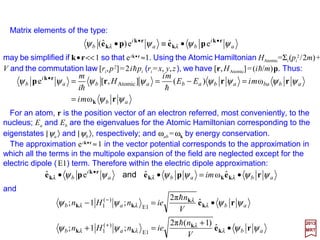

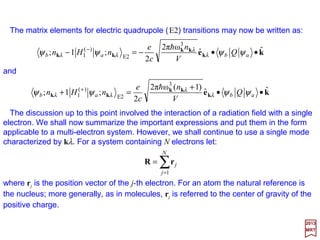

![Matrix elements of the type:

maybesimplifiedif k•r<<1so that eik•r ≈1. Using the Atomic Hamiltonian HAtomic=Σi(pi

2/2m)

+V and the commutation law [ri,p2]=2ihpi (ri =x, y,z), we have [r,HAtomic] =(ih/m)p. Thus:

2017

MRT

For an atom, r is the position vector of an electron referred, most conveniently, to the

nucleus; Ea and Eb are the eigenvalues for the Atomic Hamiltonian corresponding to the

eigenstates |ψa〉 and |ψb〉, respectively; and ωab =ωk by energy conservation.

The approximation eik•r ≈1 in the vector potential corresponds to the approximation in

which all the terms in the multipole expansion of the field are neglected except for the

electric dipole (E1) term. Therefore within the electric dipole approximation:

and:

a

i

bra

i

rb ψψψψ rkrk

pkepke ••

•≡• e)(ˆe])(ˆ[

ab

abbaabababa

i

b

mi

miEE

mi

H

i

m

ψψ

ψψψψψψψψ

r

rrrp

k

rk

ω

ω)(],[e Atomic

=

=−==•

hh

abrabra

i

br im ψψψψψψ rkepkepke k

rk

•=•• •

)(ˆω)(ˆe)(ˆ and

abr

r

rarb

abr

r

rarb

V

n

ienHn

V

n

ienHn

ψψψψ

ψψψψ

rke

k

kk

rke

k

kk

•

+

=+

•=−

+

−

)(ˆ

]1)([2π

)(;1)(;

)(ˆ

)(2π

)(;1)(;

E1

)(

1

E1

)(

1

h

h

168](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-hydrogen-130507131157-phpapp01/85/Part-V-The-Hydrogen-Atom-168-320.jpg)

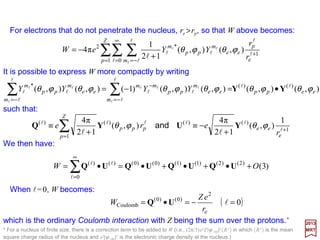

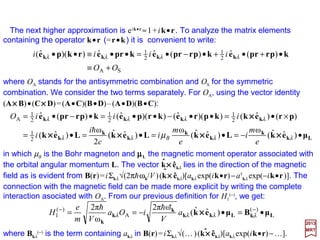

](ˆˆ[

ω

)](ˆˆ[

2

ω

)](ˆ[

)()](ˆ[)]()(ˆ[)]()(ˆ[)()(ˆ

2

1

2

1

2

1

2

1

A

rrBrr

rrrr

e

m

i

e

m

i

c

i

i

iiiO

××××××××××××××××

××××

µ

h

SA

2

1

2

1

)()(ˆ)()(ˆ)(ˆ)]()(ˆ[

OO

iiii rrrr

+≡

•+•+•−•=••≡•• kprrpkekprrpkekrpkerkpke

LL

k

k

µkBµkekkk •=•−== −−

)()](ˆˆ)[(

ω2π

)(

ω

2π )(

A

)(

1 rrrr a

V

iOa

Vm

e

H ××××

hh

µB is the Bohr magneton and µµµµL (=µBL) the magnetic moment operator associated with

the orbital angular momentum L. The vector k××××êr (k) lies in the direction of the magnetic

field as is evidentfrom B(r)=iΣkΣr√(2πhωk/V )[k××××êr (k)][ar (k)exp(ik•r)−ar

†(k)exp(−ik•r)].

The connection with the magnetic field can be made more explicit by writing the

complete interaction asociated with OA. From our previous definition for H1

(−), we get:

ˆ

ˆ

where Br

(−)(k)is the term containingar(k) inB(r)=iΣkΣr√(...)[k××××êr(k)][ar(k)exp(ik•r)−...].ˆ

169](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-hydrogen-130507131157-phpapp01/85/Part-V-The-Hydrogen-Atom-169-320.jpg)

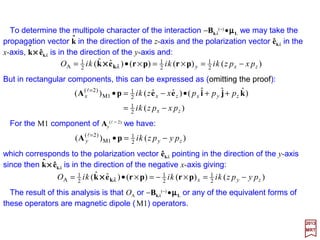

(

)ˆˆˆ()ˆˆ()(

2

1

2

1

M1

)2(

zx

zyxzxx

pxpzki

pppxzki

−=

++•−=•=

kjieepA l

)()( 2

1

M1

)2(

zyy pypzki −=•=

pA l

which corresponds to the polarization vector êr(k) pointing in the direction of the y-axis

since then k××××êr(k) is in the direction of the negative x-axis giving:ˆ

)()()()](ˆˆ[ 2

1

2

1

2

1

A zyxr pypzkikikiO −=×−=ו= prprkek ××××

170](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-hydrogen-130507131157-phpapp01/85/Part-V-The-Hydrogen-Atom-170-320.jpg)

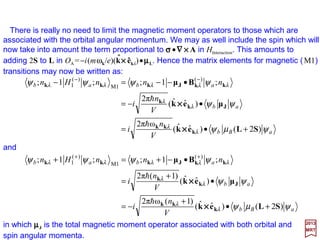

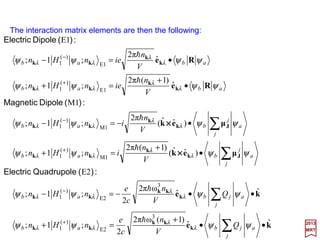

![2017

MRT

in which µµµµJ is the total magnetic moment operator associated with both orbital and

spin angular momenta.

There is really no need to limit the magnetic moment operators to those which are

associated with the orbital angular momentum. We may as well include the spin which

will now take into amount the term proportional to ΣΣΣΣ•∇∇∇∇××××A in HInteraction. This amounts to

adding 2S to L in OA =−i(mωk/e)[k××××êr(k)]•µµµµL. Hence the matrix elementsformagnetic

(M1) transitions may now be written as:

ˆ

aBbr

r

abr

r

rarrbrarb

V

n

i

V

n

i

nnnHn

ψµψ

ψψ

ψψψψ

)2()](ˆˆ[

)(ω2π

)](ˆˆ[

)(2π

)(;)(1)(;)(;1)(; )(

M1

)(

1

SLkek

k

µkek

k

kkBµkkk

k

J

J

+•=

•−=

•−−=− −−

××××

××××

h

h

aBbr

r

abr

r

rarrbrarb

V

n

i

V

n

i

nnnHn

ψµψ

ψψ

ψψψψ

)2()](ˆˆ[

]1)([ω2π

)](ˆˆ[

]1)([2π

)(;)(1)(;)(;1)(; )(

M1

)(

1

SLkek

k

µkek

k

kkBµkkk

k

J

J

+•

+

−=

•

+

=

•−+=+ ++

××××

××××

h

h

and:

171](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-hydrogen-130507131157-phpapp01/85/Part-V-The-Hydrogen-Atom-171-320.jpg)

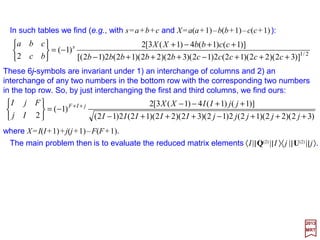

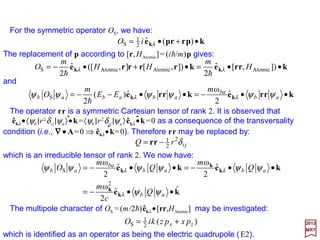

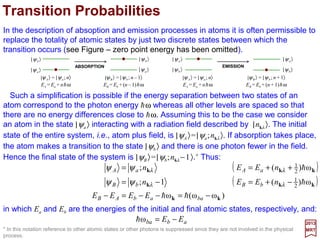

![For the symmetric operator OS, we have:

The replacement of p according to [r,HAtomic] = (ih/m)p gives:

2017

MRT

and:

which is identified as an operator as being the electric quadrupole (E2).

krrkekrrke ••−=••−−= abr

ba

abrabab

m

EE

m

O ψψψψψψ )(ˆ

2

ω

)(ˆ)(

2

S

h

kprrpke •+•= )()(ˆ2

1

S riO

krrkekrrrrke ••=•+•−= ]),[)(ˆ

2

]),[],([)(ˆ

2

AtomicAtomicAtomicS H

m

HH

m

O rr

hh

jirQ δ2

2

1−= rr

which is an irreducible tensor of rank 2. We now have:

)(2

1

S zx pxpzkiO +=

kke

kkekke

k

k

ˆ)(ˆ

2

ω

)(ˆ

2

ω

)(ˆ

2

ω

2