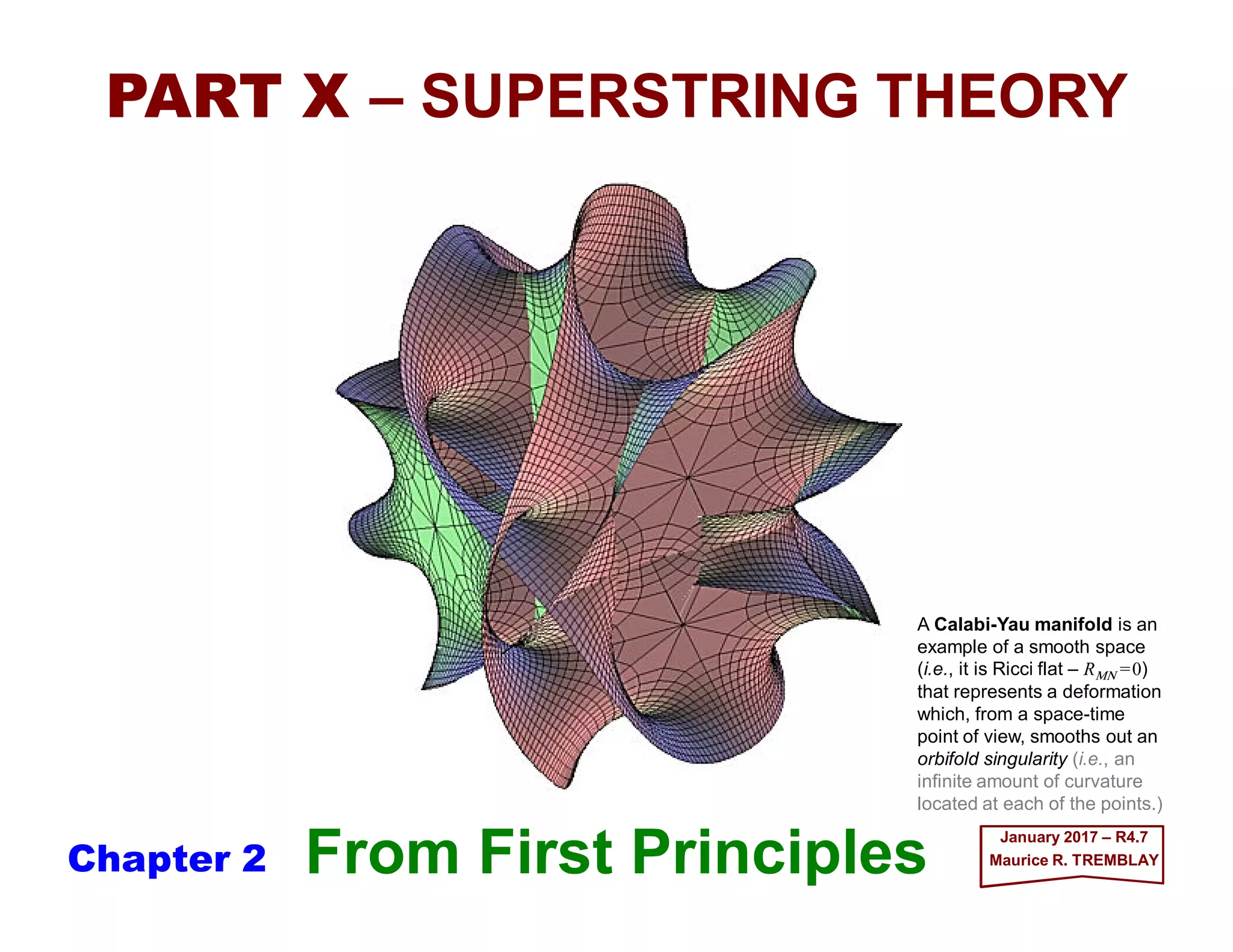

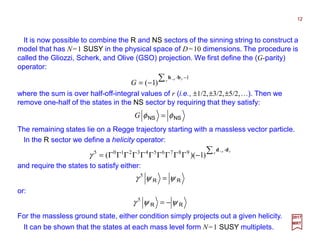

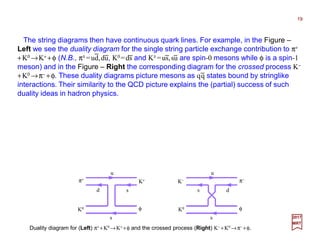

A Calabi-Yau manifold is a smooth space that represents a deformation which smooths out an orbifold singularity. This document discusses superstring theory and fermions in string theories. It introduces the spinning string action and shows that the Neveu-Schwarz model contains a tachyon ground state while the Ramond model contains massless fermions. Combining the two sectors using the Gliozzi-Scherk-Olive projection results in a model with N=1 supersymmetry in ten dimensions.

![If all elementary particles are to be described by strings, it is necessary to introduce

fermionic degrees of freedom. One method of doing this is to invoke the spinning string.

We recall that the Lagrangian S=−[1/(4πα′)]∫dξ 0dξ 1√hhab(∂x/∂ξ a)⋅(∂x/∂ξ b) (c.f., The

Classical Bosonic String chapter) in D dimensions can be interpreted as a set of D

scalar fields xµ(ξ 0,ξ 1) on the two-dimensional world sheet described by ξ 0,ξ 1. To define

the spinning string, we add a similar set of two-dimensional Majorana spinors, λµ(ξ 0,ξ 1),

and use, instead of S=−[1/(4πα′)]∫dξ 0dξ 1 ηab(∂x/∂ξ a)⋅(∂x/∂ξ b) (c.f., The Classical

Bosonic String chapter) the Lagrangian of N=1 SUGRA in two space-time dimensions.

The action can be written as:

3

2017

MRT

∫ ∂−∂∂

′π

−= )(

4

1 2

µ

µ

µ

µ

λρληξ

α

b

a

ba

ab

ixxdS

Fermions in String Theories

where ρ a are two-dimensional Dirac matrices that obey:

abba

ηρρ 2},{ =

with:

−

=

10

01ab

η

A convenient representation of the ρ-matrices is:

−

=

=

01

10

01

10 10

ρρ and

As usual λ is our last equation for S above denotes λ†ρ 0.

_](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/102-st-170117233532/85/PART-X-2-Superstring-Theory-3-320.jpg)

![(N.B., This action S above has been obtained by starting from the general N=1

SUGRA Lagrangian in two dimensions, which contains a zweibein ea

α and a world-sheet

Majorana spin-3/2 field ψ a. These have been eliminated by using reparametrization

invariance and local SUSY so that we can work in a superconformal gauge in which ea

α =

δ a

α and ψα=0).

4

2017

MRT

By the way, the λµ are spinors on the two dimensional world sheet, but are vectors in

the physical D-dimensional space, so it is not obvious at this stage how, or whether, this

theory can produce fermions (i.e., space-time spinors).

We follow the procedure of the The Classical Bosonic String chapter to obtain the

classical equations of motion. Consider first the open string. For the bosonic variable,

xµ, we obtain the same equations as before, which have the general open string solution

[1/√(2α′)]xµ(τ,σ)=qµ +αm

µτ +iΣn≠0(1/n)αn

µ exp(−inτ)cos(nσ). On the other hand,

minimization of the action with respect to variations in λµ gives the Dirac equation:

0=∂ µ

λρ a

a

as one would expect, provided that we impose the boundary condition (N.B., This

condition ensures that the boundary terms vanish when we integrate by parts):

( )π0010

andatT

== σλδρρλ µ

µ](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/102-st-170117233532/85/PART-X-2-Superstring-Theory-4-320.jpg)

![With the representation of ρa given by the matrices ρ0 =[::] and ρ1 =[::] above, if we

write the two-spinor λ as:

5

2017

MRT

=

2

1

λ

λ

λ

the boundary condition λµTρ0ρ1δλµ=0 above becomes:

( )002211 ==⋅−⋅ σλδλλδλ at

This is satisfied if λ1=±λ2 (and δλ1=±δλ2) at each end of the string. The relative sign

between λ1 and λ2 is simply a matter of convention, which we will fix by choosing:

( )021 == σλλ at

But at the other end of the string, σ =π, there are still two distinct choices:

21 λλ =:(R)modelthe Raymond

and

21 λλ −=:(NS)modelthe Schwarz-Neveu](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/102-st-170117233532/85/PART-X-2-Superstring-Theory-5-320.jpg)

![Using λ=[λ1 λ2]T above we can write the Dirac equation ρa∂aλµ =0, in component

form:

6

2017

MRT

0)(0)( 21 =∂−∂=∂+∂ λλ στστ and

which have the general solution:

)()( 2211 στλστλ +=−= ff and

where f1 and f2 are arbitrary functions. The requirement λ1 =λ2 (at σ =0) above then

gives:

21 ff =

and the alternative boundary conditions λ1 =λ2 (R) and λ1 =−λ2 (NS) above become:

)()()π2()()()π2( 1111 NSandR ττττ ffff −≡+≡+

It follows that we can write, in analogy to [1/√(2α′)]xµ(τ,σ)=qµ +αm

µτ +iΣn≠0(1/n)αn

µ

⋅exp(−inτ)cos(nσ), &c., for the R model:

∑

′= +−

−−

n

ni

ni

nd )(

)(

e

e

),( στ

στ

αστλ

where n are the integers 0,±1,±2,… with dn*=d−n. For the NS model:

∑

′= +−

−−

r

ri

ri

rb )(

)(

e

e

),( στ

στ

αστλ

where r are the half-odd-integers ±1/2,±3/2,±5/2,… with br*=b−r.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/102-st-170117233532/85/PART-X-2-Superstring-Theory-6-320.jpg)

![In the NS model, we find the mass spectrum:

9

2017

MRT

2

12

−+=′ ∑∑ −−

r

rr

n

nn rM bb ⋅⋅⋅⋅αααα⋅⋅⋅⋅ααααα

The −½ arises from the reordering needed to get the operators into normal order. We

can evaluate this term by following the regularization method of M 2 “=” (1/α′)Σn αααα−n⋅⋅⋅⋅ααααn +

[1/(2α′)]ΣµΣn[αn

µ,α−n

µ ] of the The Quantum Bosonic String chapter et seq.ˆ

ˆ ˆ

We put:

Then we use:

−

−

++=

+=′

∑∑∑∑

∑∑

>>

−−

−−

00

2

2

2

”“

2

1

2

1

”“

rnr

rr

n

nn

r

rr

n

nn

rn

D

r

rM

bb

bb

⋅⋅⋅⋅αααα⋅⋅⋅⋅αααα

⋅⋅⋅⋅αααα⋅⋅⋅⋅ααααα

∑∑∑∑∑

∞

=

−

−

−

−

−−

=

−

−−==−=

1,...2,1,...,,...,,,,...,, 2

1

1

2

1

2

4

2

2

2

4

2

3

2

2

2

1

2

5

2

3

2

1 n

s

s

s

s

ss

r

s

nnrrr

or:

∑∑

∞

=

−=

1,...,,

2

1

2

5

2

3

2

1 n

nr](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/102-st-170117233532/85/PART-X-2-Superstring-Theory-9-320.jpg)

above is therefore, using ζ(−1)=−1/12 (c.f., The

Quantum Bosonic String chapter):

10

2017

MRT

2

1

12

1

2

3

2

2

12

1

2

3

2

2

”“

2

3

2

2

1

−=⋅⋅

−

−=

−⋅

−

=

⋅

−

∑

∞

=

DD

n

D

n

when D=10 (N.B.,Σnn=1+2+3+…+∞=−1/12=ζ(−1)!)

The ground state of the NS spinning string is therefore a tachyon with M2 =−1/(2α′)

from α ′M2 =Σnαααα−n⋅⋅⋅⋅ααααn +Σrrb−r ⋅⋅⋅⋅br −½ above. The first excited state is a massless vector

(i.e., b−½ |0〉), while at M2 =−1/(2α′) we have a vector (i.e., αααα−1 |0〉) and an antisymmetric

tensor (i.e., b−½

µb−½

ν |0〉). (N.B., In this model there are no space-time fermions).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/102-st-170117233532/85/PART-X-2-Superstring-Theory-10-320.jpg)

![In contrast, the R model does have fermions. To see how they arise, note that a

special case of the anticommutation relations {dn

µ,dm

ν}=−ηµνδn+m,0 above is:

11

2017

MRT

µννµ

η−=},{ 00 dd

which implies:

µµ

Γ= id

2

1

0

the Γµ being the Dirac matrices appropriate for the dimension D=10. These operators

only have spinor representations, so the ground state has to be a D=10 Lorentz spinor.

(i.e., we cannot define a unique vacuum state |0〉 satisfying d0 |0〉 =0 because this would

be incompatible with (d0

µ)2=±½ which follows from {d0

µ,d0

ν}=−ηµν above). Other states

are then obtained by acting on this ground-state spinor with dn and αn (n<0). The mass

spectrum is given by:

∑=

−− +=′

,..3,2,1

2

)(

n

nnnn nM dd ⋅⋅⋅⋅αααα⋅⋅⋅⋅ααααα

where the absence of any reordering constant is due to the fact that it cancels between

the αn and dn terms. The ground state |½〉 is therefore a massless fermion. The first

excited space has [mass]2 equal to 1/α′ and is a Rarita-Schwinger spin-3/2 particle (e.g.,

formed by α−1

µ and d−1

µ acting on the ground-state spinor).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/102-st-170117233532/85/PART-X-2-Superstring-Theory-11-320.jpg)

![We now turn to the closed spinning string. Again the bosonic part is like that discussed

in the The Classical Bosonic String chapter and yields [1/√(2α′)]XL

µ = ½qµ +α0

µ (τ +σ )+

½iΣn≠0(1/n)αn

µ L exp[−2in(τ +σ )] and [1/√(2α′)]XR

µ =½qµ +α0

µ (τ −σ )+½iΣn≠0(1/n)αn

µ R

⋅exp[−2in(τ −σ)]. For the fermionic variables we have the general right- or left-moving

solutions given in λ1 = f1(τ −σ ) and λ2 = f2(τ +σ ) above, and we must also impose the

boundary conditions the Raymond model (R): λ1 =λ2 and the Neveu-Schwarz model

(NS): λ1 =−λ2 above, which relate λ(τ ,0) to λ(τ ,π). There are clearly four possibilities

according to whether we impose R or NS type boundary conditions on the right- and left-

moving excitations:

13

2017

MRT

)0,()π,(-

)0,()π,(

)0,()π,(

-

)0,()π,(

)0,()π,(

-

)0,()π,(-

2,12,1

22

11

22

11

2,12,1

τλτλ

τλτλ

τλτλ

τλτλ

τλτλ

τλτλ

−=

=

−=

−=

=

=

NSNS

RNS

NSR

RR](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/102-st-170117233532/85/PART-X-2-Superstring-Theory-13-320.jpg)

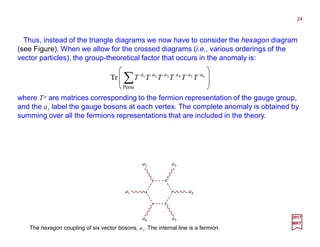

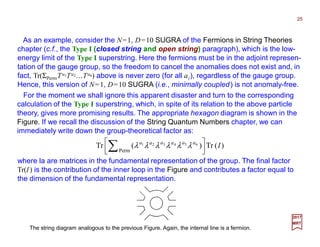

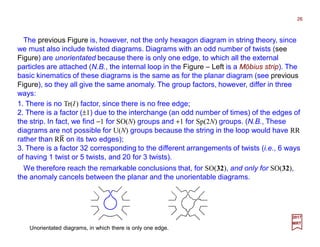

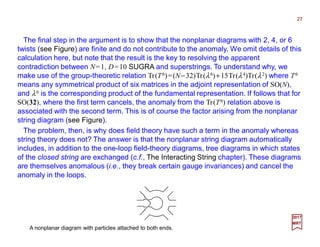

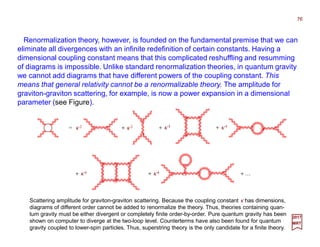

![The relevant tree diagram involves the exchange of the antisymmetric tensor field BMN

of D=10 SUGRA (c.f., Fermions in String Theories chapter) as in the Figure. The group

factor associated with this diagram clearly factorizes like the last term of the Tr(T6)

relation above. To understand the couplings in the Figure, we first note that BMN appears

in the Lagrangian through a term:

28

where HMNP is the curl of BMN, that is:

2017

MRT

MNP

MNP HH

A coupling of two vector bosons to four vector bosons through the exchange of the antisymmetric tensor

field BMN.

BMN

][ NPMMNP BH ∂=

where […] means that the expression has to be antisymmetrical in the bracketed indices

(e.g., the same way that gauge field appears in the Lagrangian through Fµν =∂µ Aν −∂ν Aµ

≡∂[µ Aν ] as in L =−¼Fµν Fµν−Jµ Aµ of the PART VIII – THE STANDARD MODEL: Field

Equations chapter).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/102-st-170117233532/85/PART-X-2-Superstring-Theory-28-320.jpg)

![In order to maintain a supersymmetry when Yang-Mills multiplets are included, H must

be modified to H′, given by:

29

where ω(Y-M)

MNP is the so-called Yang-Mills Chern-Simon 3-form defined by (c.f.,

Appendix V: A Brief Review of Groups and Forms):

2017

MRT

)M-Y(

ωMNPMNPMNP HH −=′

−= ][][

)M-Y(

3

1

Trω PNMNPMMNP AAAgFA

Here AM and FMN are matrices in the adjoint representation of the gauge group.

It is clear that when we use H′ rather than H in HMNP HMNP above there is a coupling

between BMN and two vector field AM (i.e., the left-hand vertex of the previous Figure).

However, ω(Y-M) is not gauge-invariant, so, in order to maintain the gauge invariance of

the Lagrangian, B must also transform nontrivially under a gauge transformation, a

somewhat surprising conclusion since it appears to be a gauge singlet.

On the other hand, the coupling of B to four gauge bosons, which can occur through a

term:

)(Tr 10987654321

10987654321

MMMMMMMMMM

MMMMMMMMMM

FFFFBε

is only gauge-invariant if B is invariant. It follows that the diagram in the previous Figure

violates gauge invariance, and it is this that allows it to cancel the anomaly!](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/102-st-170117233532/85/PART-X-2-Superstring-Theory-29-320.jpg)

![The key idea of the heterotic string (meaning hybrid vigor) is to treat right- and left-

moving modes differently. It is a closed string in D=10 for which we take the action to be

(c.f., S=−[1/(4πα′)]∫dξ 0dξ 1ηab(∂x/∂ξ a)⋅(∂x/∂ξ b) of the The Classical Bosonic String and

S=−[1/(4πα′)]∫d2ξ(η ab∂a xµ∂b xµ −iλµρa∂λµ) of the Fermions in String Theories chapters):

32

2017

MRT

∫

∂−∂−

∂

∂

∂

∂

′

−= +− A

A

ba

ab xx

ddS λλψψ

ξξ

ηξξ

α

µ

µµ

µ

22

π4

1 10

where ψ µ and λA are Majorana-Weyl fermions on the two-dimensional world-sheet. The

ψ µ are right-moving modes (i.e., functions only of ξ 0 −ξ 1), and the λA (with A=1,2,…,N)

are a set of Lorentz-scalar, left-moving modes (i.e., functions only of ξ 0 +ξ 1). Derivatives

with respect to ξ 0 ±ξ 1 are denoted by ∂±, respectively. From the ψ µ and the right-moving

parts of xµ we construct and N=1 SUSY theory as in the Fermions in String Theories

chapter.

The Heterotic String

_](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/102-st-170117233532/85/PART-X-2-Superstring-Theory-32-320.jpg)

![We now separate the solution into L- and R-moving parts (c.f., xµ(τ,σ )=XL

µ(τ +σ )+XR

µ

(τ −σ)). For the xµ the general solution is again given by [1/√(2α′)]XL

µ = ½qµ +α0

µ (τ +σ )

+½iΣn≠0(1/n)αn

µ L exp[−2in(τ +σ )] and [1/√(2α′)]XR

µ =½qµ +α0

µ (τ −σ )+½iΣn≠0(1/n)αn

µ R

⋅exp[−2in(τ −σ)]. For the y component, however, we have:

37

2017

MRT

α′

=

2

r

c

with:

)()(),( στστστ −++= RL

YYy

and:

∑ +−

++

++=

′ n

niL

n

L

n

i

kc

c

l

qY )(2

e

1

2

)(2

2

1

2

1

2

1 στ

βστ

α

∑ −−

+−

−+=

′ n

niR

n

R

n

i

kc

c

l

qY )(2

e

1

2

)(2

2

1

2

1

2

1 στ

βστ

α

in which we have introduced the dimensionless constant:](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/102-st-170117233532/85/PART-X-2-Superstring-Theory-37-320.jpg)

![Now, with quantization, q and l/c become conjugate variables (c.f., [qµ,α0

ν ]=−igµν):

38

2017

MRT

n

c

lr

π2

2

π2

=

′α

However, q is a periodic variable with period 2πr/√(2α′), so the uniqueness of the wave

function requires that:

iclq −=],[

where n=±integer and hence l has to be a (±) integer too.

The mass of the string as seen in the 25-dimensional space is given by:

00

2 2

αα

α

⋅

′

=M

where of course the scalar product is in 25-dimensions (yikes!). We evaluate this, as in

the The Classical Bosonic String chapter, using the zero-frequency Virasoro constraints

(c.f., Ln

L,R≡−½Σk=±∞ αk

L,R ⋅αn−k

L,R =0 and Ln

L=Ln

R =0, for all n), which here take the form:

02

4

1

0

2

0

00 =−

+−⋅+⋅ ∑∑ ≠

−

≠

−

n

L

n

L

n

n

L

n

L

n kc

c

l

ββαααα

The last two terms in each case are the contributions of the y component.

02

4

1

0

2

0

00 =−

−−⋅+⋅ ∑∑ ≠

−

≠

−

n

R

n

R

n

n

R

n

R

n kc

c

l

ββαααα

and:](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/102-st-170117233532/85/PART-X-2-Superstring-Theory-38-320.jpg)

![We shall now show that a generalization of this procedure can be used to give an

alternative description of the heterotic string. As before we take the right-moving modes

to be the D=10 superstring. In contrast to the heterotic action S above we assume that

the left-movers are bosonic and exist in D=26 dimensions,16 of which are compactified.

The general procedure for this compactification is to introduce into the 16-dimensional

Euclidean space a set of 16 vectors eq (q=1,2,…,16), and then to identify points labelled

y and y+√(2α ′)πeq, for and q. We have inserted the factor √(2α′) here so that the eq are

dimensionless (N.B., This is fine-tuning of the model and is necessary to preserve mo-

dular invariance and to obtain the E8⊗E8 symmetry requires for consistencyof the theory).

The closed-string boundary condition (c.f., y(τ,σ +π)=y(τ,σ )+2πkr above) becomes:

41

2017

MRT

∑′+=+

q

qqk eyy π2),()π,( αστστ

where kq are a set of (±) integers.

Since the y are all left-movers (i.e., functions of τ +σ ), the usual expansion (e.g.,

[1/√(2α′)]XL

µ = ½qµ +α0

µ (τ +σ )+½iΣn≠0(1/n)αn

µ L exp[−2in(τ +σ )]) takes the form:

∑ +−

+++=

′ n

ni

n

n

i )(π2

0 e

1

2

)(

2

1

2

1 στ

στ

α

βpyy

Consistency with y(τ,σ +π)=y(τ,σ )+√(2α′)πΣqkqeq above then requires:

that is, p must lie on the lattice defined by the vectors eq.

∑= qqk ep](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/102-st-170117233532/85/PART-X-2-Superstring-Theory-41-320.jpg)

![Now, in contrast to the situation where, as in previous examples, we have both L and R

contributions to y, the coefficients of σ and τ in [1/√(2α′)]y= ½y0+p(τ +σ )+½iΣn(1/n)ββββn

⋅exp[−2πin(τ +σ )] above are identical. This means that the quantum condition arising

from periodicity in y is also a condition on p. In fact, single-valuedness of the wave

function requires that exp(2πikq p⋅⋅⋅⋅eq) be equal to unity for all kq, which implies:

42

2017

MRT

the kq being integers and the eq vectors of the so-called dual (or inverse) lattice

satisfying:

∑= qqk ep ~~

~ ~

qqqq ′′ = δee ⋅⋅⋅⋅~

In general a lattice eq and its dual eq do not have any common points, so that p=Σqkqeq

and p=Σqkqeq have no solutions. We consider the case when the two lattices are

identical (i.e., when the lattice is self-dual for this is necessary to preserve modular

invariance, since modular transformations mix the lattice and its dual). This is clearly

sufficient to guarantee the consistency of p=Σqkqeq and p=Σqkqeq; that it is necessary

follows from the requirement of modular invariance of loop amplitudes.

~

~ ~

~ ~](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/102-st-170117233532/85/PART-X-2-Superstring-Theory-42-320.jpg)

![The first requirement that we shall impose on the compactification is that it must give N

=1 SUSY in four dimensions. This is necessary because the mass scale of the theory is

the Planck mass MP and only SUSY seems able to prevent the scalars that are required

by electroweak symmetry breaking from acquiring a mass of this order. On the other

hand, N>1 SUSY is incompatible with the existence of chiral fermions. (N.B., The trivial

compactification onto a 6-torus would leave intact the N=4 SUSY obtained from N=1

SUSY in 10 dimensions).

45

2017

MRT

To obtain N=1 SUSY, the vacuum state must be annihilated by one SUSY generator:

00 =Q

It follows that:

00],[0 =ψQ

and hence that:

000 =δψ

where ψ is any field and δψ is its change under infinitesimal SUSY transformation. We

apply these results to the gravitino ψΜ, for which:

L+= ε

κ

δψ ΜΜ D

1

where ε is an infinitesimal spinorial parameter (c.f., PART IX – SUPERSYMMETRY:

Local Supersymmetry). We assume the omitted terms in δψΜ above involve the field

H′ defined in H′=H−ω(Y-M) −ω(Lor) of the Anomalies chapter and vanish in the vacuum.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/102-st-170117233532/85/PART-X-2-Superstring-Theory-45-320.jpg)

![So, the relation 〈0|δψΜ |0〉=0 above requires the existence of a covariantly constant

spinor ε that satisfies:

46

2017

MRT

This leads to interesting restrictions on the manifold. To find them we note that DΜ ε =0

implies that:

0=εσ ΡΣ

ΜΝΡΣR

0=εΜD

0],[ =εΝΜ DD

Recalling the form of the covariant derivative of a spinor Dµψ =∂µψ −¼iωµ

mnσmnψ (c.f., op

cit: The Inclusion of Matter), and using Rµν

mn =∂µων

mn −∂νωµ

mn +ωµ

m

pων

pn +ων

m

pωµ

pn (c.f.,

op cit: The Einstein Lagrangian), we can write this as:

where RΜΝΡΣ is the Riemann-Christoffel tensor for D=10. We seek a compactification in

which the space takes the form Τ (4)⊗Β (6), where Τ (4) is physical space-time and Β (6) is

the 6-dimensional compact manifold, so RΜΝΡΣ σ ΡΣε =0 above separates into two

equations of similar form.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/102-st-170117233532/85/PART-X-2-Superstring-Theory-46-320.jpg)

![Since we require Τ (4) to be maximally symmetric, we have [c.f., Eq. (13.2.9) of S.

Weinberg, Gravitation and Cosmology, Wiley]:

47

2017

MRT

which can only be satisfied for a nontrivial ε if:

0

6

=εσ ρσ

νσµρ gg

R

)(

12

νρµσνσµρµνρσ gggg

R

R −=

where R is the scalar curvature, so the D=4 part of RΜΝΡΣ σ ΡΣε =0 becomes:

0=R

Thus, the requirement of N=1 SUSY implies a zero cosmological constant, a successful

prediction, but one that is qualified by the presence of other contributions resulting from

the breaking of SUSY, &c., which, unless canceled by fine-tuning, would be many orders

of magnitude too large.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/102-st-170117233532/85/PART-X-2-Superstring-Theory-47-320.jpg)

![In the Compactification and Chiral Fermions chapter we found that the gauge group that

emerges when the gauge fields and spin connection are identified is E6⊗E8. The

massless states of observable physics are singlets of E8 and lie in the 27 of E6, which is

therefore the Grand Unified Theories (GUTs) group. Like for GUT we require E6 to be

broken at a high energy (i.e., at or near the compactification scale, preferably to the

gauge group of the Standard Model – SU(3)⊗SU(2)⊗U(1)). However, the usual Higgs

method of symmetry breaking is not possible here because it requires states of negative

[mass]2, whereas we have taken care to ensure that all masses are zero (or at least real).

54

2017

MRT

Compactification and Symmetry Breaking

Fortunately, there is an alternative. It relies on the fact that although a zero field-

strength tensor (i.e., Fµν=0) implies that the potential (i.e., Aµ) can be made equal to zero

by a gauge transformation, this can only be achieved globally if the manifold is simply

connected. (N.B., On such a manifold any closed loop can be contracted to a point; thus,

the surface of a sphere is simply connected while the surface of a torus is not – see

Figure). We shall find that the presence of noncontractible (so-called Wilson) loops

allows a new symmetry-breaking scheme.

Illustrating the differences between a simply and multiply connected manifold. The small loops are drawn

on the surface of the manifolds. The right-hand loop on the torus (Right) cannot be smoothly contracted

to a point.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/102-st-170117233532/85/PART-X-2-Superstring-Theory-54-320.jpg)

( xfx ψψ =

will rule out many solutions.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/102-st-170117233532/85/PART-X-2-Superstring-Theory-55-320.jpg)

![We can now break a symmetry by identifying each element f of F with an element, say

Uf, of the gauge group (i.e., E6), and replacing ψ (x)=ψ [ f (x)] above by:

56

2017

MRT

)]([)( xgfxgf ≡

Using this relation twice, we find:

)()]([ xUxf f ψψ =

)()]}([{)]([)( xUxgfxgUxUU gffgf ψψψψ ===

where fg denotes the mapping:

Hence, from Uf Ugψ =Uf gψ above:

gfgf UUU ≡

which shows that the Uf form a group and hence that F is mapped onto a discrete

subgroup of the gauge group (i.e., E6).

The unbroken subgroup, G, of E6 consists of all the elements V for which ψ (x)=ψ [ f (x)]

above is invariant:

)()]([ xVUxfV f ψψ =

Using ψ (x)=ψ [ f (x)] we can write the left-handed side of this as:

)()]([ xUVxfV f ψψ =

Since these two last equations are true for all ψ, we find:

0],[ =−= VUUVUV fff

So, the unbroken symmetry is the subgroup of E6 that commutes with all the Uf !](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/102-st-170117233532/85/PART-X-2-Superstring-Theory-56-320.jpg)

![Two important features of this method of symmetry breaking should now be noted:

First, it is clear that the massless states that survive (i.e., those that satisfy the single-

valuedness requirement, ψ (x)=ψ [ f (x)], above), will lie in particular representations of

the unbroken subgroup G. However, different representations of G will, in general, arise

from different E6 zero modes on Β. Thus, physical fermions, even of one family, will not

necessarily belong to a particular E6 representation. Hence for example, there will be E6

relation between the couplings of the Higgs bosons to the quarks and leptons, which is

good because there is no obvious symmetry in the quark and lepton masses. Second,

there are severe limitations as to the degree of breaking that can be obtained by this

method. The group E6 contains a maximal subgroup SU(3)⊗SU(3)⊗SU(3) and we would

hope to identify one SU(3) with color and break the product of the other two SU(3)s to

SU(2)⊗U(1). But in fact, this is not (quite yet) possible.

57

2017

MRT

One of the successes of the conformal field theory approach is that, with only a few mild

constraints,one finds reasonably acceptable candidates for practical phenomenology.

For example, the heterotic string contains the gauge group E8⊗E8. By making a few

reasonable assumptions about its broken phase, it is possible to break this group down

to E6⊗E8 and finally to E6, which contains the Standard Model’s gauge group,

SU(3)⊗SU(2)⊗U(1). The basic fermion multiplet naturally occurs in the 27 multiplet of E6,

which is consistent with known grand unified theory (GUT) phenomenology. Thus, it is

surprising that, with very few minimal assumptions, we are naturally led to the following

symmetry breaking scheme:

)(U)(SU)(SUEEEEE 68688 123 ⊗⊗→→⊗→⊗](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/102-st-170117233532/85/PART-X-2-Superstring-Theory-57-320.jpg)

![Now, suppose,first, that F is a cyclic group consisting of one element f, which satisfies:

58

2017

MRT

1=N

f

Then, from Uf Ug =Uf g above:

1)( =N

fU

Now if Uf is to commute with SU(3)⊗SU(2)⊗U(1), it can be written parametrically as:

⊗

⊗

=

−

ε

δ

γ

β

β

β

α

α

α

00

00

00

00

00

00

00

00

00

1

fU

with α3 =γδε =1 because SU(N) matrices have unit determinant. In order to satisfy (Uf)N =

1 above we also require:

1===== NNNNN

εδγβα

The unbroken symmetry consists of all matrices that commute with Uf =[MMM]⊗[MMM]⊗[MMM]

above:

−

⊗⊗

−⊗⊗⊗

−

⊗

200

010

001

000

010

001

200

010

001

IIIIII and,

)(U)(U)(U)(SU)(SU 11123 ⊗⊗⊗⊗

where the generators of the three U(1) factors may respectively be taken to be:](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/102-st-170117233532/85/PART-X-2-Superstring-Theory-58-320.jpg)

![Several important differences from electromagnetism should now be noted:

63

2017

MRT

First, the higher-order terms, neglected in this last equation, give rise to interactions

between three and more gravitons. Thus, like gluons but unlike photons, gravitons

interact with each other!

Second, we note that canonical quantization involves writing causal commutation rules

such that commutators between field operators (e.g., hµν (x), hµν (x)) are zero when x and

x are spacelike-separated (i.e., when c2∆t2 <∆r2 and s2 > 0). However, the concept of a

spacelike interval is only defined with respect to some metric and since our metric is

itself an operator, we have a major difficulty. It is usual to define the commutators of the

theory with respect to the background metric ηµν , but then it is not obvious that strict

causality is maintained.

This third difference is that, unlike the fine structure constant of QED for the

electromagnetic coupling, α =e2/hc, which is dimensionless, the corresponding quantity

in gravity (i.e., GN /hc) has dimension [mass]−2. Thus the index of divergence of the

interaction (i.e., δi ≡bi+(3/2) fi +di −4, where bi is the number of bosons, fi is the number

of fermions, and di is the number of derivatives) is equal to +2, which has the serious

consequence that, at least according to simple power-counting arguments, the theory is

not renomalizable!](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/102-st-170117233532/85/PART-X-2-Superstring-Theory-63-320.jpg)

]([

)(

)( 33

t

E

pp

t

td

txd

pxT xxxx −−−−−−−− δδ

νµν

µνµ

==

* These next 11 slides are taken in part from S. Weinberg, Gravitation and Cosmology, Wiley (1973), pp. 285-289.

2017

MRT

since x0(t)=t and pµ =Edxν/dt, an assembly of gravitons, all of which have four-momenta

pµ =hkµ, is:

N

ω

νµ

νµ

kk

T h=

where N is the number of gravitons per unit volume. Comparing this with the result for a

gravitational plane wave (i.e., 〈tµν 〉=(1/16πGN)kµ kν (|ε+|2 +|ε−|2)) we then conclude that the

number density of gravitons with helicity ±2 in a plane wave is N± =(ω/16πhGN)|ε±|2 (N.B.,

GN =6.6732 ×10−8 dyn cm2 g−2 is Newton’s gravitation constant). The total number density

is:

−=+= −+

2

*

2

1

)(

16π

ω σ

σνµ

νµ

εεε

NGh

NNN

65](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/102-st-170117233532/85/PART-X-2-Superstring-Theory-65-320.jpg)

![Since S(ω) and I(ω) above remain valid even if the gravitational radiation is not in

equilibrium with matter, so that n(ω) is not given by n(ω)dω=(ω2/π2)dω[exp(hω/kBT)−1]−1

above. It is only necessary that the matter be in thermal equilibrium at temperature T.

For instance, we can calculate the rate S(ω) of spontaneous emission of gravitons per

unit volume and per unit frequency interval in a nonrelativistic gas of particles of number

density na (e.g., of type a particles, &c.):

∑ ∫ Ω

Ω=

),(

252

sin

π5

8

ω ba

ab

abbaab

N

d

d

dvnn

G

d

dP

θ

σ

µ

2017

MRT

This ω−3 behavior can make A(ω) surprisingly large for low-frequency gravitons in

gases at high temperature. However, the effect of induced emission is to reduce the

effective absorption rate by a factor hω/kBT. There does not appear to be any situation

in the present universe where the absorption of gravitational radiation plays any

important role!

∑ ∫ Ω

Ω=

),(

252

3

sin

ω5

π8

)ω(

ba

ab

abbaab

N

d

d

dv

G

A θ

σ

µ nn

h

and dividing it by hω, provided that the graviton frequency ω is in the range ωc <<ω<<kBT/h,

where ωc is the collision frequency, µ is the reduced mass, v is the relative velocity, and θ is

the scattering angle in the barycentric frame. Applying S(ω)=(ω2/π2)exp(−hω/kBT)A(ω)

above then gives the absorption rate of such gravitons as:

71](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/102-st-170117233532/85/PART-X-2-Superstring-Theory-71-320.jpg)

![The preceding remarks describe what may be called a semiclassical theory of

gravitation. The development of a true quantum theory of gravitation is unfortunately

much more difficult.

∑ −

+=

r

xkir

r

xkir

r aadxh ]e)()(e)()([)( *)(†)(3 σ

σ

σ

σ

νµνµνµ εε kkkkk

2017

MRT

One approach is to construct an interaction Hamiltonian that can create and destroy

gravitons, and then calculate transition probabilities as a power series in this interaction.

Usually the Hamiltonian would be built up out of quantum fields, of the form:

where εµν =ε (r)

µν (k) is a polarization tensor for a graviton of momentum hk and helicity r,

and ar(k) and ar

†(k) are the corresponding annihilation and creation operators, characte-

rized by the transformation relation:

srsr aa δδ )(])(),([ 3†

kkkk ′=′ −−−−

The difficulty in this approach comes from the fact that the operator hµν above cannot be

a Lorentz tensor as long as the helicity sum is limited to the physical values r=±2 (i.e., a

true tensor would have helicities 0 and ±1 as well as ±2). It is true that we can start with

a true tensor and then subject εµν to a gauge transformation that will eliminate the

unphysical helicities 0 and ±1, but once we choose a gauge in this way, hµν is no

longer a tensor.

and

0])(),([])(),([ ††

=′=′ kkkk srsr aaaa

72](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/102-st-170117233532/85/PART-X-2-Superstring-Theory-72-320.jpg)

![To illustrate some of these abstract concepts, it will prove useful to take the simplest

possible nontrivial example, O(2), or rotations in two dimensions. Even the simplest

example is surprisingly rich in content. Our goal is to construct the irreducible

representations of O(2), but first we have to make a few definitions.

81

2017

MRT

invariant22

=+ yx

If we rotate the plane through an angle θ, then the coordinates [x,y] of the same point

in the new system are given by:

−

=

y

x

y

x

θθ

θθ

cossin

sincos

We will abbreviate this by (N.B., sum over repeated indices):

jjii

xx O=

where x1 =x and x2 =y. (N.B., For the rotation group, it makes no difference whether we

place the index i as a superscript, as in xi, or as a subscript, as in xi).

We know that if we draw a straight line on a piece of 8½×11 paper, then rotate this

sheet of paper, the length of the straight line drawn on the paper will remain constant. If

[x,y] describe the coordinates of a point on a plane, then this means that, by the

Pythagorean theorem, the following length is an invariant under a rotation about the

origin:*

* Recall that we expressed this earlier as (N.B., in the following slides you can associate the invariant in component form too):

invariant=ii xx](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/102-st-170117233532/85/PART-X-2-Superstring-Theory-81-320.jpg)

![For small angles θ, the matrix equation [:]=[::][:] above can be reduced to:

82

2017

MRT

yyyxxx δδ −=+= and

where:

xyyx θδθδ −== and

since cosθ →1 and sinθ →θ as θ →0, or simply:

jjii

xx εθδ =

where ε ij is antisymmetric and ε 12 =−ε 21 =1. These matrices form a group; for example,

we can write down the inverse of any rotation, given by O−1(θ) = O(−θ):

==−

10

01

)(O)(O 1θθ

We can also prove associativity, since matrix multiplication is associative.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/102-st-170117233532/85/PART-X-2-Superstring-Theory-82-320.jpg)

![The fact that these matrices preserve the invariant length places restrictions on them.

To find the nature of these restrictions, let us make a rotation on the invariant distance:

83

2017

MRT

that is, this is invariant if the Oij matrix is orthogonal:

jjkkijijkkijjiii

xxxxxxxx === ]OO[OO

≠

=

==

kj

kjkjkiji

if

if

0

1

OO δ

where δ is called the Kronecker delta, or, more symbolically:

11 =OOT

To take the inverse of an orthogonal matrix, we simply take its transpose. The unit matrix

1 is called the metric of the group.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/102-st-170117233532/85/PART-X-2-Superstring-Theory-83-320.jpg)

![Let us now take the determinant of both sides of the following equation:

85

2017

MRT

1)]O([det)O(detO)(det)OO(det 2

=== TT

This means that the determinant of O is equal to ±1. If we take detO=1, then the

resulting subgroup is called SO(2), or the special orthogonal matrices in two dimensions.

The rotations that we have been studying up to now are members of SO(2).

−

=

10

01

P

This last transformation corresponds to a parity transformation:

yyxx −→→ and

A parity transformation P takes a plane and maps it into its mirror image, and hence it is

a discrete, not continuous transformation, such that P2 =1.

However, there is also the curious subset when detO=−1. This subset consists of

elements of SO(2) time the matrix:](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/102-st-170117233532/85/PART-X-2-Superstring-Theory-85-320.jpg)

![For our purposes, we are primarily interested in the transformation properties of fields.

For example, we can calculate how a field φ(x) transforms under rotations. Let us

introduce the operator:

87

2017

MRT

∂

∂

−

∂

∂

=

∂

∂

≡ 1

2

2

1

x

x

x

xi

x

xiL j

iji

ε

Let us also define:

Li

U θ

θ e)( =

Then we define a scalar field as one that transforms under SO(2) as:

scalar)()()()( 1

==−

xUxU φθφθ

(N.B., To prove this equation, we use the fact that exp(A)Bexp(−A)= B+[ A,B]+

(1/2!)[ A,[A,B]]+(1/3!)[ A,[A,[A,B]]]+…) with the commutator [A,B]=AB−BA, then we

reassemble these terms via a Taylor expansion to prove the transformation law).

We can also define a vector field φ i(x), where the additional i index also transforms

under rotations:

vector)()(O)()()( 1

=−=−

xUxU jjii

φθθφθ

This result can be generalized to include an arbitrary field φ a(x) that transforms under

some representation of SO(2) labeled by some index a. Then the field transforms as:

)()()()()( 1

xUxU bbaa

φθθφθ −=−

D

where Dab is some representation, either reducible or irreducible, of the group.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/102-st-170117233532/85/PART-X-2-Superstring-Theory-87-320.jpg)

(O[)( jijjiiji

BABA θθ=

One simple way of generating higher representations of O(2) is simply to multiply

several vectors together. The product AiB j, for example, transforms as follows:

This matrix Oii(θ)Oj j(θ) forms a representation of SO(2). It has the same multiplication

rule as O(2), but the space upon which it acts is 2×2 dimensional. We call any object that

transforms like the product of several vectors a tensor.

In general, a tensor T i jk… under O(2) is nothing but an object that transforms like the

product of a series of ordinary vectors:

tensorOO

,,,,,, 21221121

==

LL

L

jjjijiii

TT

The transformation of T i jk… is identical to the transformation of the product x ix jx k….

This product forms a representation of O(2) because the following matrix:

has the same multiplication rule as SO(2).

)(O)(O)(O)(O

,,,,,,;,,, 22112121

θθθθ NNNN jijijijjjiii

L

LL

≡

- -](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/102-st-170117233532/85/PART-X-2-Superstring-Theory-89-320.jpg)

![These three antisymmetric matrices τ i can be explicitly written as:

93

2017

MRT

−−==

−

−==

−

−==

000

001

010

001

000

100

010

100

000

321

iii zyx

ττττττ and,

By inspection, this set of matrices can be succinctly represented by the fully

antisymmetric ε ijk tensor as:

kjikji

iετ −=][

where ε 123 =+1. These antisymmetric matrices, in turn, obey the following properties:

kkjiji

i τεττ −=],[

This is an example of a Lie algebra (not to be confused with the Lie group). The

constants ε ijk appearing in the algebra are called the structure constants of the algebra.

A complete determination of the structure constants of any algebra specifies the Lie

algebra, and also the group itself.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/102-st-170117233532/85/PART-X-2-Superstring-Theory-93-320.jpg)

![For small angles θ i, we can write the transformation law as:

94

2017

MRT

jkkjii

xx θεδ =

As before (i.e., Lk=iε ijk xi ∂ j earlier) we will introduce the operators:

kjkjii

xiL ∂≡ ε

We can show that the commutation relations of Li satisfy those of SO(3). Let us construct

the operator:

ii

Lii

U θ

θ e)( =

Then a scalar and a vector field, as before, transform as follows:

)()(]O[)()()()()(O)()()( 111

xUxUxUxU jjiijjii

φθθφθφθθφθ −−−

=−= or

As in the case of O(2), we can also find a relationship between O(3) and a unitary group.

Consider the set of all unitary, 2×2 matrices with unit determinant. These matrices form a

group, called SU(2), which is called the special unitary group in two dimensions. This

matrix has 8−4−1=3 independent elements in it. Any unitary matrix, in turn, can be

written as the exponential of a Hermitian matrix H, where H=H*T =H†:

Hi

U e=

Again, to prove this relation, simply take the Hermitian conjugate of both sides:

1†

ee

†

−−−

=== UU HiHi](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/102-st-170117233532/85/PART-X-2-Superstring-Theory-94-320.jpg)

![Since an element of SU(2) can be parametrized by three numbers, the most

convenient set is to use the Hermitian Pauli spin matrices. Any element of SU(2) can be

written as:

95

2017

MRT

2

e

ii

i

U σθ

=

where:

−

==

−

==

==

10

01

0

0

01

10 321 zyx

i

i

σσσσσσ and,

where σ i satisfy the relationship:

22

,

2

k

kji

ji

i

σ

ε

σσ

=

We now have exactly the same algebra as SO(3) as in [τ i,τ j]=iε ijkτ k above. Therefore,

we can say:

)(SU~)(SO 23](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/102-st-170117233532/85/PART-X-2-Superstring-Theory-95-320.jpg)

![To make the correspondence more precise, we will expand the exponential and then

recollect terms, giving us:

96

2017

MRT

2

ee

iiii

ii θσθτ

↔

where θ i =niθ and (ni)2 =1. The correspondence is then given by:

+

=

2

sin)(

2

cose )2( θ

σ

θθσ kki

ni

ii

where the left-hand side is a real, 3×3 orthogonal matrix. Even though these two

elements exist in different spaces, they have the same multiplication law. This means

that there should also be a direct way in which vectors [x,y,z] can be represented in

terms of these spinors. To see the precise relationship, let us define:

+

−

=•=

zyix

yixz

h xσx)(

Then the SU(2) transformation:

1−

= UhUh

is equivalent to the SO(3) transformation:

xOx •=](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/102-st-170117233532/85/PART-X-2-Superstring-Theory-96-320.jpg)

![Now let us take a subgroup of GL(N,R), the orthogonal group O(N), which consists of

all possible N×N real matrices that are orthogonal:

97

2017

MRT

∑

−

=

=

)1(½

1

eO

NN

i i

i

λθ

The real numbersθ i are called the parameters of the group, and there are thus ½N(N−1)

parameters in O(N) (e.g., N=3, we get 3). The number of parameters of a lie group is

called its dimension.The commutatorof two of these generators yields another generator:

k

k

jiji f λλλ =],[

where the f s are called the structure constants of the algebra(N.B.,sum over repeated

k as usual). Notice that the structure constants determine the algebra completely.

This obviously satisfies all four of the conditions for a group. Any orthogonal matrix can

be written as the exponential of an antisymmetric matrix:

1=T

OO

It is easy to see that:

A

eO=

In general, an exponential matrix has ½N(N−1) independent elements. Thus we can

always choose a set of ½N(N−1) linearly independent matrices, called the generators λi,

such that we can write any element of O as:

1

OeeO −−

=== AAT

T](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/102-st-170117233532/85/PART-X-2-Superstring-Theory-97-320.jpg)

![Notice that if we take cyclic combinations of three commutators, we get an exact

identity:

98

2017

MRT

0]],[,[0]],[,[]],[,[]],[,[ ][ ==++ kjijikikjkji λλλλλλλλλλλλ or

By expanding out these commutators, we find that the combinations identically cancels

to zero. This is called the Jacobi identity and must be satisfied for the group to close

properly. By expanding out the Jacobi identity, we now have a constraint among the

commutators that must be satisfied, or else the group does not close:

00 ][ ==++ m

lk

l

ji

m

lj

l

ik

m

li

l

kj

m

lk

l

ji ffffffff or

Of course, the set of orthogonal matrices closes under multiplication(i.e.,O(θ 1)O(θ 2) =

O(θ 3)). A more complicated problem is to prove that this particular parametrization of the

orthogonalgroup,withgeneratorsandparameters,closesundermultiplication.Let us write:

CBA

eee =

Fortunately, the Baker-Campbell-Hausdorff theorem shows that C equals A plus B plus

all possible multiple commutators of the A and B (i.e., the Baker-Campbell-Hausdorff

formula is exp(A)exp(B)=exp(A +B+½[ A,B]+…)). But since the A and B satisfy the Jacobi

identities,the set of all possible multiple commutators of A and B only creates linear

combinations of the generators. Thus, the group closes under multiplication.

Notice that the structure constants of the algebra form a representation, called the

adjoint representation. If we write the structure constants as a matrix f k

ij =[λk]ij.Thus,

the structure constants themselves form a representation.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/102-st-170117233532/85/PART-X-2-Superstring-Theory-98-320.jpg)

![We can always choose the commutation relations to be:

99

2017

MRT

dacbcadbcbdadbcadcba

MMMMMM δδδδ ++−=],[

for the antisymmetric matrix Mab. One convenient representation of the algebra is now

given by:

a

j

b

i

b

j

a

iji

ba

M δδδδ −~][

which, we can show, satisfies the commutation relations of the group.

Let us define a set of N elements xi that transforms as a vector under the group O(N):

jjii xx O=

In general, we can also define a tensor Tµ1,µ2,µ3,…,µp

of rank p that transforms in the same

way as the product of p ordinary vectors xµi

:

pppp

TT µµµµµνµνµνµννννν ,...,,,,,,,,...,,, 321332211321

OOOO L=](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/102-st-170117233532/85/PART-X-2-Superstring-Theory-99-320.jpg)

![In addition to the vector representation of O(N), we have the spinor representation of

the group. Let us define the Clifford algebra:

100

2017

MRT

baba

δ2},{ =ΓΓ

Now define a representation of the generators in terms of these Clifford numbers:

],[

4

1 baba

i

M ΓΓ=

The Clifford numbers themselves transforms as vectors:

)(],[ acbbcacba

iM Γ−Γ=Γ δδ

In general, these Clifford numbers can be represented by 2N×2N matrices [Γa]µν for the

group O(2N). Therefore, a spinor ψµ that transforms under O(2N) has 2N elements and

transforms as:

ννµ

ζ

µ ψψ ]e[

baba

M

=

where the Ms are written in terms of the Clifford algebra and the ζ variables are

parameters.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/102-st-170117233532/85/PART-X-2-Superstring-Theory-100-320.jpg)

![For the group O(2N+1), we need one more element. This missing element is Γ2N+1 =

Γ1Γ2…Γ2N. We can easily check that this new element allows us to construct all the M

matrices for O(2N+1).

101

2017

MRT

invariant=ii xx

Let us now try to construct invariants under the group. Orthogonal transformations

preserve the scalar product:

If xi =Oij xj, then:

iiii xxxxxx == OOT

This invariant can be written:

jjii xx δ

where the metric is δij. In principle, we could have a metric with alternating positive and

negative signs along the diagonal,ηij, which would create elements in ηij, then the set of

matrices that preserve this form is called O(N, M ):

lilkkjji ηη =O]O[ T

where ε (i)=±1. If all the elements of ε are positive, this gives a generalization of the

group O(N). If the signs alternate, then the group is noncompact. Special cases

include: 1) Projective group, O(2,1); 2) Lorentz group, O(3,1); 3) de Sitter Group,

O(4,1); 4) anti-de Sitter group, O(3,2); 5) Conformal group, O(4,2).

and

jiji i δεη )(=](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/102-st-170117233532/85/PART-X-2-Superstring-Theory-101-320.jpg)

![For example, the de Sitter group can be constructed by taking the generators of O(4,1)

and then writing the fifth component as Pa ~ M5a, then the algebra becomes:

102

2017

MRT

++−=

−=

=

dacbcadbcbdadbcadcba

cbabcacba

baba

MMMMMM

PPMP

MPP

ηηηη

ηη

],[

],[

],[

:)1,(O 4

Notice that this is almost the algebra of the Poincaré group. In fact, if we make the

substitution:

aa

PrP ±→

then the only commutator that changes is:

baba

M

r

PP 2

1

],[ =

where r is called the de Sitter radius. This means that if we go around a circle in de

Sitter space and return to the same spot, we will be rotated by a Lorentz transforma-

tion from our original orientation. Notice that if r goes to infinity, we have the Poincaré

group. Thus, r corresponds to the radius of a five-dimensional universe such that, if r

goes to infinity, it becomes indistinguishable from the flat four-dimensional space of

Poincaré. Letting the radius go to infinity is called the Wigner-Inönü contraction and

will be used extensively in supergravity theories. After the contraction, the de Sitter

group becomes the Poincaré group.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/102-st-170117233532/85/PART-X-2-Superstring-Theory-102-320.jpg)

![The group SU(N), which stands for special unitary N×N matrices with complex

coefficients, consists of all possible N×N complex matrices that have unit determinant

and are unitary:

103

2017

MRT

1=†

UU

Any unitary matrix can be written as the exponential of a Hermitian matrix, H† =H, that is:

H

U e=

We can show that U† =exp(−iH†)=exp(−iH)=U−1.

Let N elements in a complex vector ui transform linearly under SU(N):

jjii uUu =

The N complex vectors ui generate the fundamental representation of the group.

invariant*

=ii uu

iikkjjiiii uuuUUuuu *†**

][ ==

If ui =Uij uj, it is easy to check that:

The metric tensor for the scalar product is again δij. If we were to reserve some of

the signs in this diagonal matrix, the groups that would preserve this metric are called

SU(N,M ). An example of this would be the conformal group SU(2,2).

−](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/102-st-170117233532/85/PART-X-2-Superstring-Theory-103-320.jpg)

![Any N×N complex traceless Hermitian matrix has N2−1 independent elements and

hence can be written in terms of N2−1 linearly independent matrices λi. Thus, any

element of SU(N) can be written as:

∑

−

=

=

12

1

e

N

i i

i

i

U

λρ

The Baker-Hausdorff theorem then guarantees that the group closes under this

parametrization and that we can write the algebra of the group as:

k

k

jiji fi λλλ =],[

again, knowledge of the structure constants f k

ij determines the algebra completely.

We can also construct representations of SU(N) out of spinors. If we have the group

O(2N ), then SU(N) is a subgroup. If we construct the elements:

)(

2

1 212 jjj

iA Γ−Γ= −

where Γ2j are Grassman variables, then the generators of SU(N) can be written as:

∑=

kj

k

kj

aja

AA

,

†

][λλ

2017

MRT

Thus, we have an explicit representation for the inclusion:

)2(O)(SU NN ⊂

104](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/102-st-170117233532/85/PART-X-2-Superstring-Theory-104-320.jpg)

![The symplectic groups Sp(2N ) are defined as the set of 2N×2N real matrices S that

preserve an antisymmetric metric η:

2017

MRT

lilkkjji ηη =S]S[ T

where:

jjii uu S=

and

−

−

=

OMMMM

L

L

L

L

0100

1000

0001

0010

jiη

105](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/102-st-170117233532/85/PART-X-2-Superstring-Theory-105-320.jpg)

![Another useful accident is:

2017

MRT

)(SU)(SU)(O 224 ⊗=

To prove this, we note that the generators Mij of O(4) can be divided into two sets:

and

},,{ 323121 MMMA =

},,{ 434142 MMMB =

Notice that the A and B matrices separately generate the algebra of O(3) and that:

0],[ =BA

Thus, we can parametrize any element of O(4) such that it splits up into a product of O(3)

and another commutating O(3). Thus, we have proved that an element of O(4) can be

split up into the product of two elements of a commutating set of SU(2) groups.

107](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/102-st-170117233532/85/PART-X-2-Superstring-Theory-107-320.jpg)

![Now, it is often convenient to describe a gauge theory (e.g., Yang-Mills theory) in the

mathematical language of forms (i.e., especially when working in higher dimensions D).

As a concrete example, we will begin by making an association with Maxwell’s theory

first, then provide a generalization to exterior calculus. Next we will review how spinors

enter into coordinate covariance and Lorentz transformations such as to pave the way

for an overview of forms as they apply in Yang-Mills theories where local gauge

invariance is important.

110

2017

MRT

Let us define the derivative operator as:

0},{ ==∧+∧∧−=∧ νµµννµµννµ

xxxxxxxxxx dddddddddd or

µ

µ

∂= xdd

Notice that because the derivatives ∂µ ≡∂/∂xµ commute (as opposed to… anticommute):

0],[ =∂∂=∂∂−∂∂ νµµννµ

we therefore obtain:

02

== ddd

which makes dddd nilpotent, by definition.

0=∧ µµ

xx dd

and

So, to start with, let the infinitesimal differentials dddd xµ be antisymmetric under an

operation ∧ that we call the wedge product; that is, the anticommutator:](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/102-st-170117233532/85/PART-X-2-Superstring-Theory-110-320.jpg)

![With these physical preliminaries out of the way, the fundamental definitions and

formulas of exterior calculus are summarized here for ready reference.

112

2017

MRT

µµ

xd=ωωωω

Basis 1-forms are defined firstly, as a coordinate basis:

and secondly, as a general basis:

νµ

ν

µ

xL d=ωωωω

where Lµ

ν are the Lorentz ‘boost’ transformations which have the matrix components:

jijij

i

i

j

ii

i nnLLnLLL δγγβ

β

γ +−==−==

−

≡= )1(

1

1

0

0

2

0

0 ,,

and Lµ

ν =[same as Lν

µ but with β replaced by −β ] where β =v/c, n1, n2, and n3 are

parameters, and n2 =(n1)2 +(n2)2+(n3)2 =1. For motion in the z- or 3-direction, the

transformation matrices reduce to the familiar form:

=

−

−

=

γγβ

γβγ

γγβ

γβγ

µ

ν

ν

µ

00

0100

0010

00

00

0100

0010

00

LL and

For example, basis 1-forms for analyzing Schwarzschild geometry around static

spherically symmetric center of attraction are ωωωω0 =(1−RS /r)½dddd t; ωωωω1 =(1−RS /r)−½dddd r;

ωωωω2 =rdddd θ ; and ωωωω3 =rsinθdddd ϕ (where RS =2GM/c2 being the Schwarzschild’s Radius).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/102-st-170117233532/85/PART-X-2-Superstring-Theory-112-320.jpg)

![In flat space, we have the equation:

118

2017

MRT

Since the derivative of a field generates parallel displacements, intuitively this equation

means that if we parallel transport a vector around a closed curve in flat space, we wind

up with the same vector.

0],[ =∂∂ νµ

In curved space, however, this is not obviously true! The parallel displacement of a

vector around a closed path on a sphere. for example, leads to a net rotation of the

vector when we have completed the circuit. Thus, the analog of the previous equation

can also be found for curved manifolds. We can interpret the covariant derivatives as the

parallel displacement of a vector and the Christoffel symbol as the amount of derivation

from flat space. If we now parallel displace a vector completely around a closed loop. we

arrive at:

σ

σ

ρνµρνµ ARA =∇∇ ],[

where:

τ

ρµ

σ

τν

τ

ρν

σ

τµ

σ

ρµν

σ

ρνµ

σ

ρνµ ΓΓ−ΓΓ+Γ∂−Γ∂=R](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/102-st-170117233532/85/PART-X-2-Superstring-Theory-118-320.jpg)

![We can now define a set of gamma matrices defined over either the tangent or the

basis space:

121

2017

MRT

µµ

γγ =aa

e

with:

νµνµ

γγ g2},{ −=

Thus, the derivative operator on a spinor becomes:

∂/≡∂=∂ µ

µ

µ

µ

γγ aa

e

With this tangent space, we can now define the covariant derivative of the spinor ψ :

ψωψψ µµµ

baba

Σ+∂=∇

where Σab is the antisymmetric product of two gamma matrices:

and ωµ

ab is called the spin connection. Notice that the spin connection is a true tensor in

the µ index.

],[

2

baba i

γγ=Σ](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/102-st-170117233532/85/PART-X-2-Superstring-Theory-121-320.jpg)

![To show that we also have local Lorentz invariance, let us make a local Lorentz

transformation:

122

2017

MRT

We can also use the O(3,1) formulation of general relativity and dispense with Christoffel

symbols. We can define:

ψψ M

e→

baba

Mµµµ ω+∂=∇

where:

are the generators of the Lorentz group. Then we can form:

],[

4

1 baba

i

M ΓΓ=

baba

MR νµνµ =∇∇ ],[

where:

bccabccabababa

R µννµµννµνµ ωωωωωω −+∂−∂=

Notice that this tensor Rµν

ab yields an alternative formulation of the curvature tensor.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/102-st-170117233532/85/PART-X-2-Superstring-Theory-122-320.jpg)