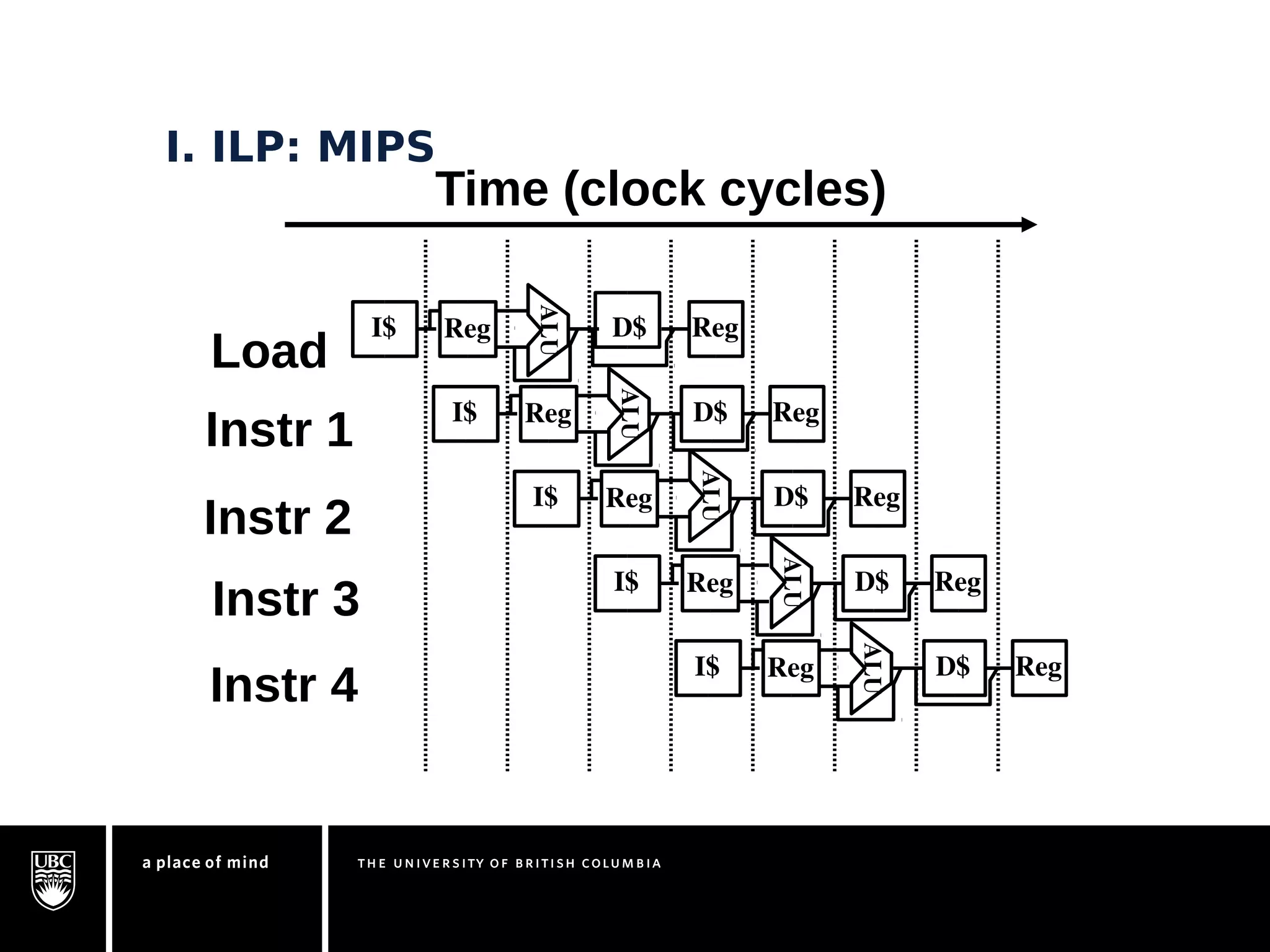

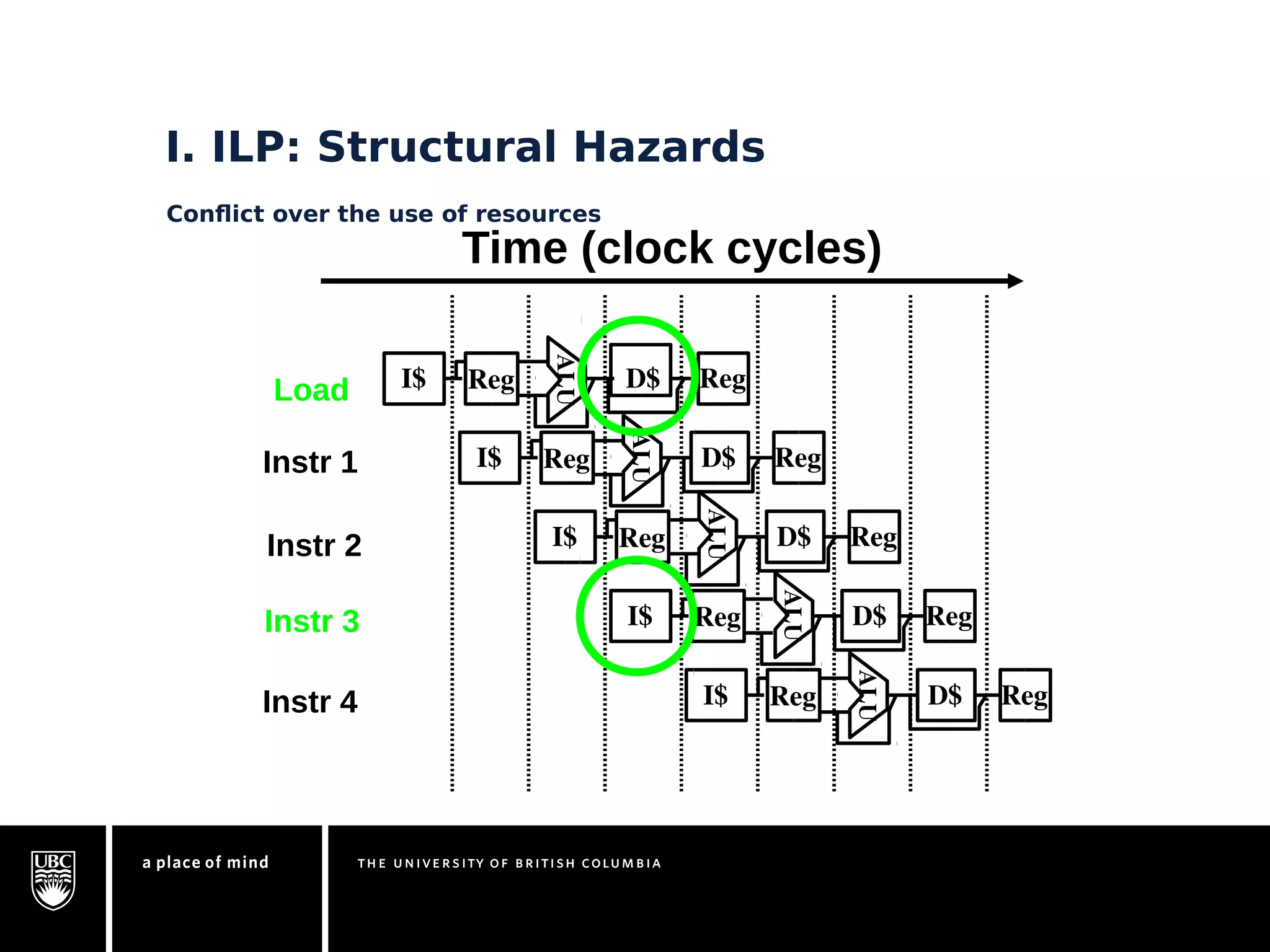

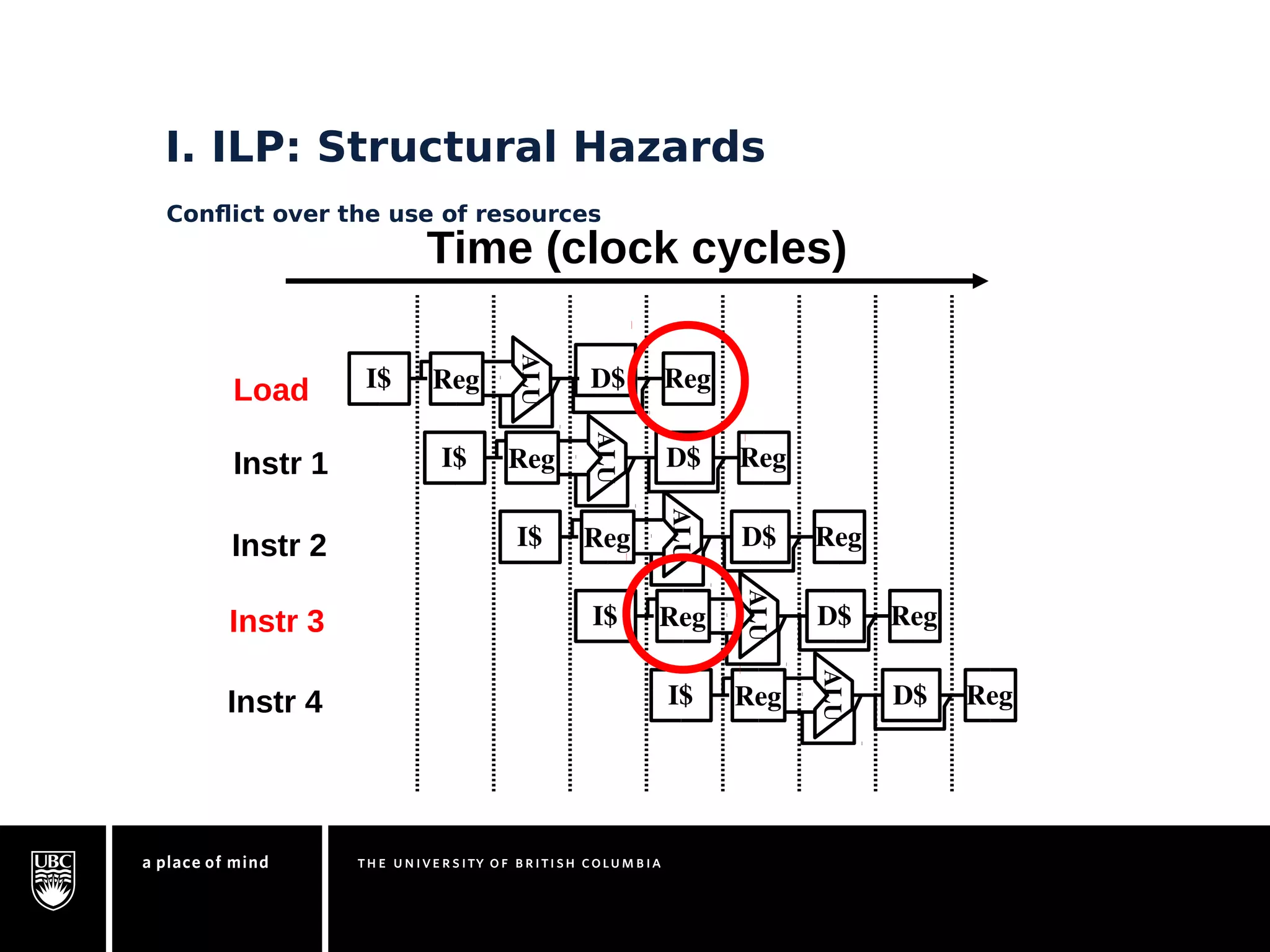

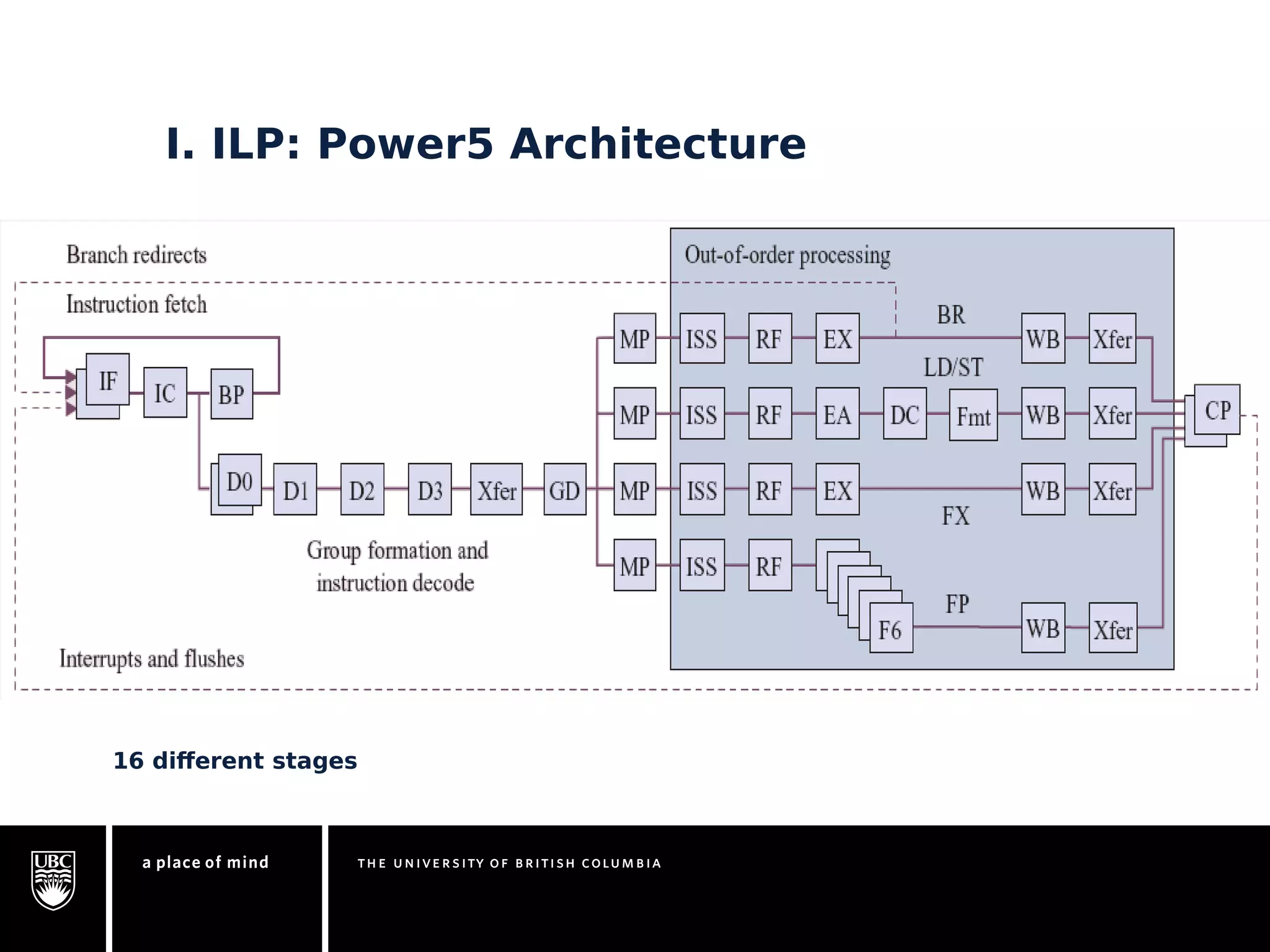

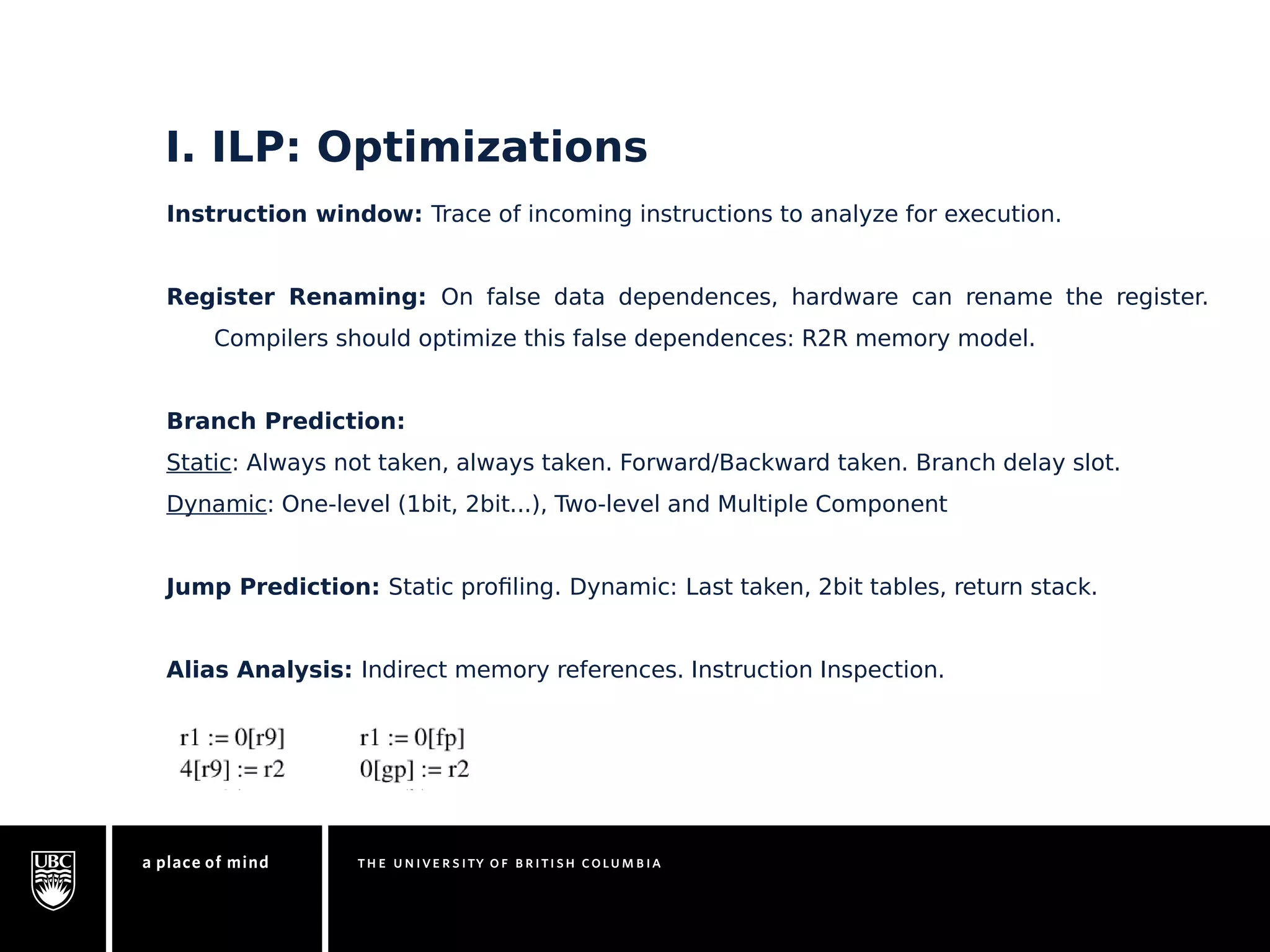

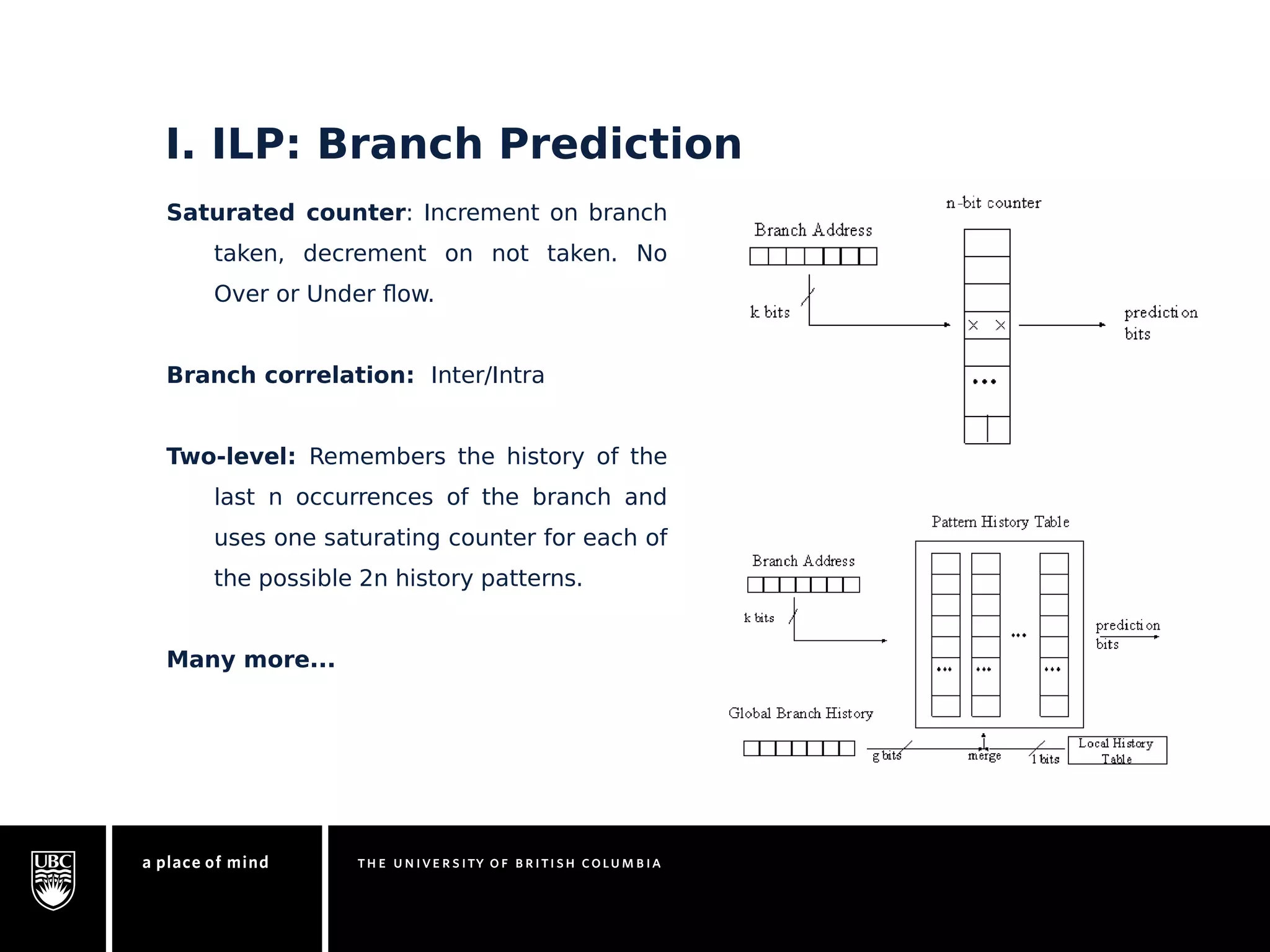

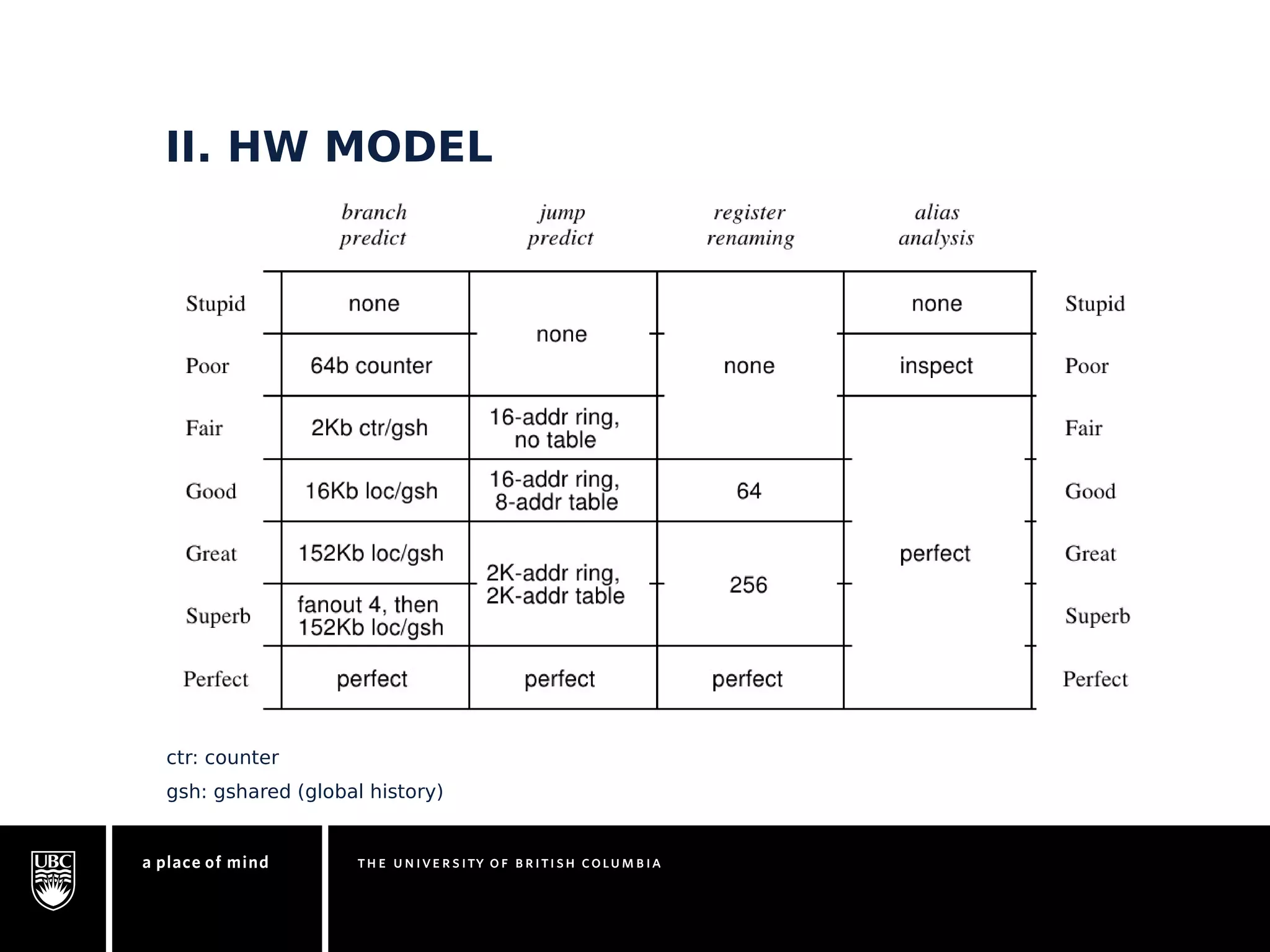

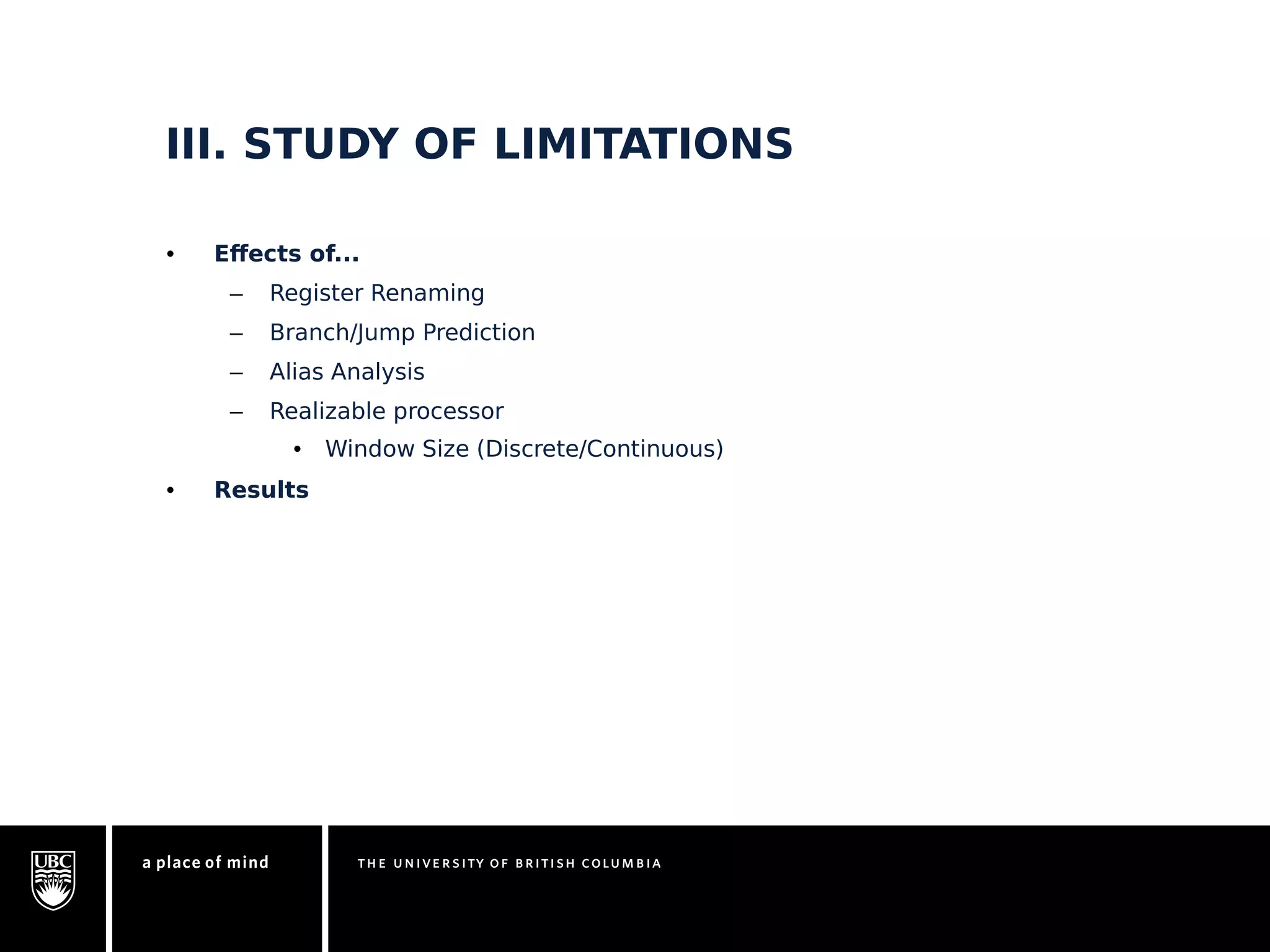

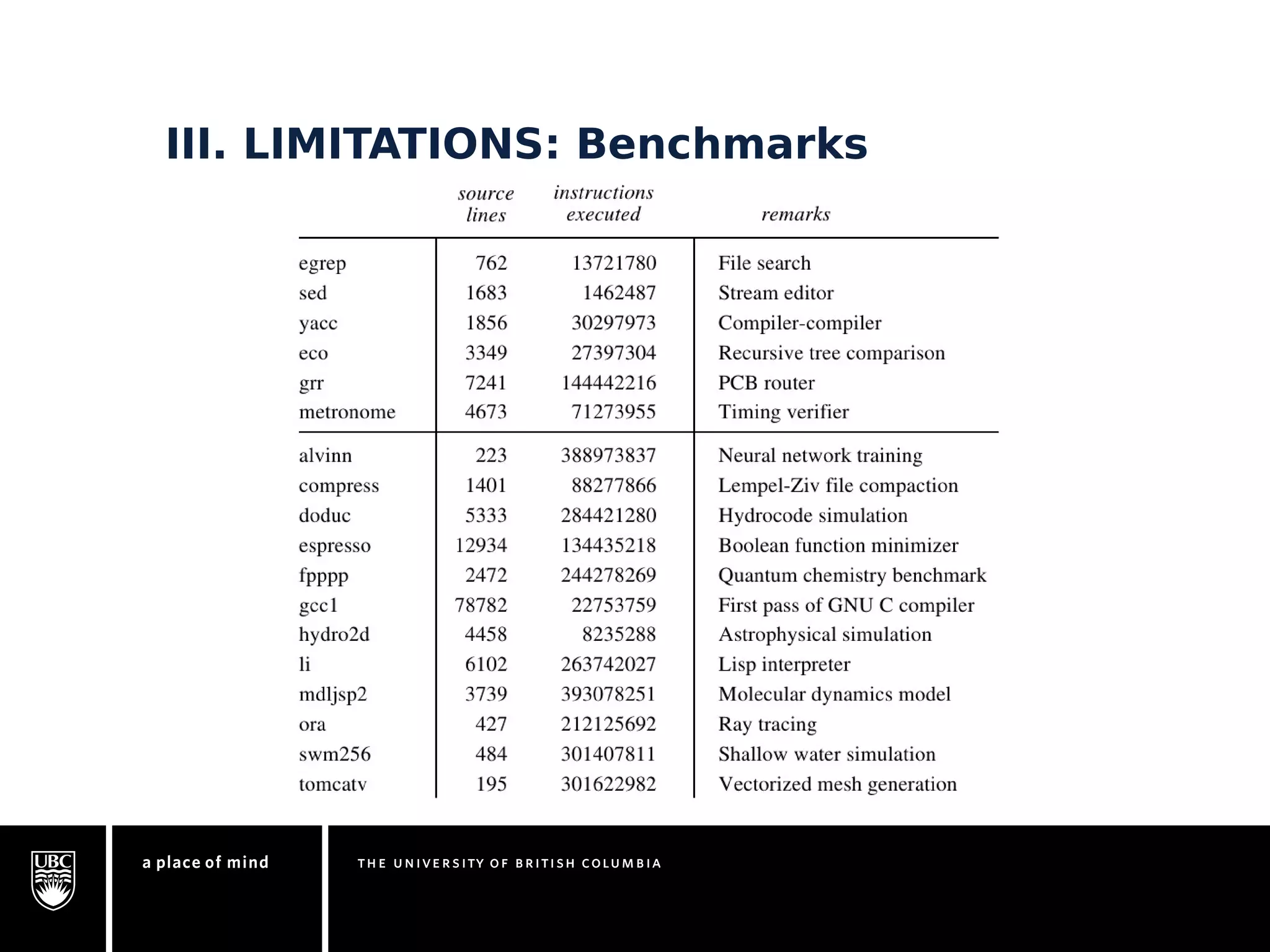

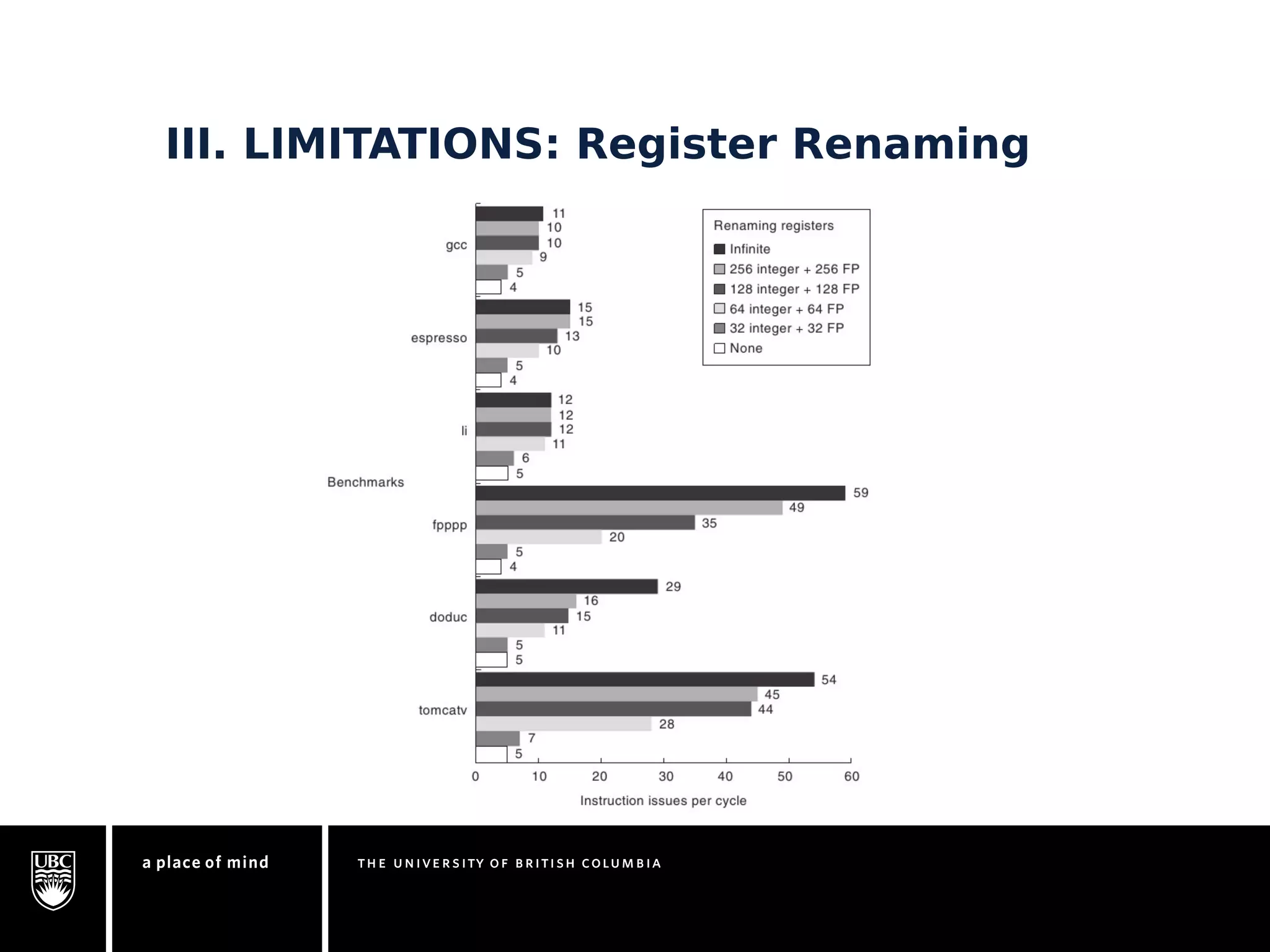

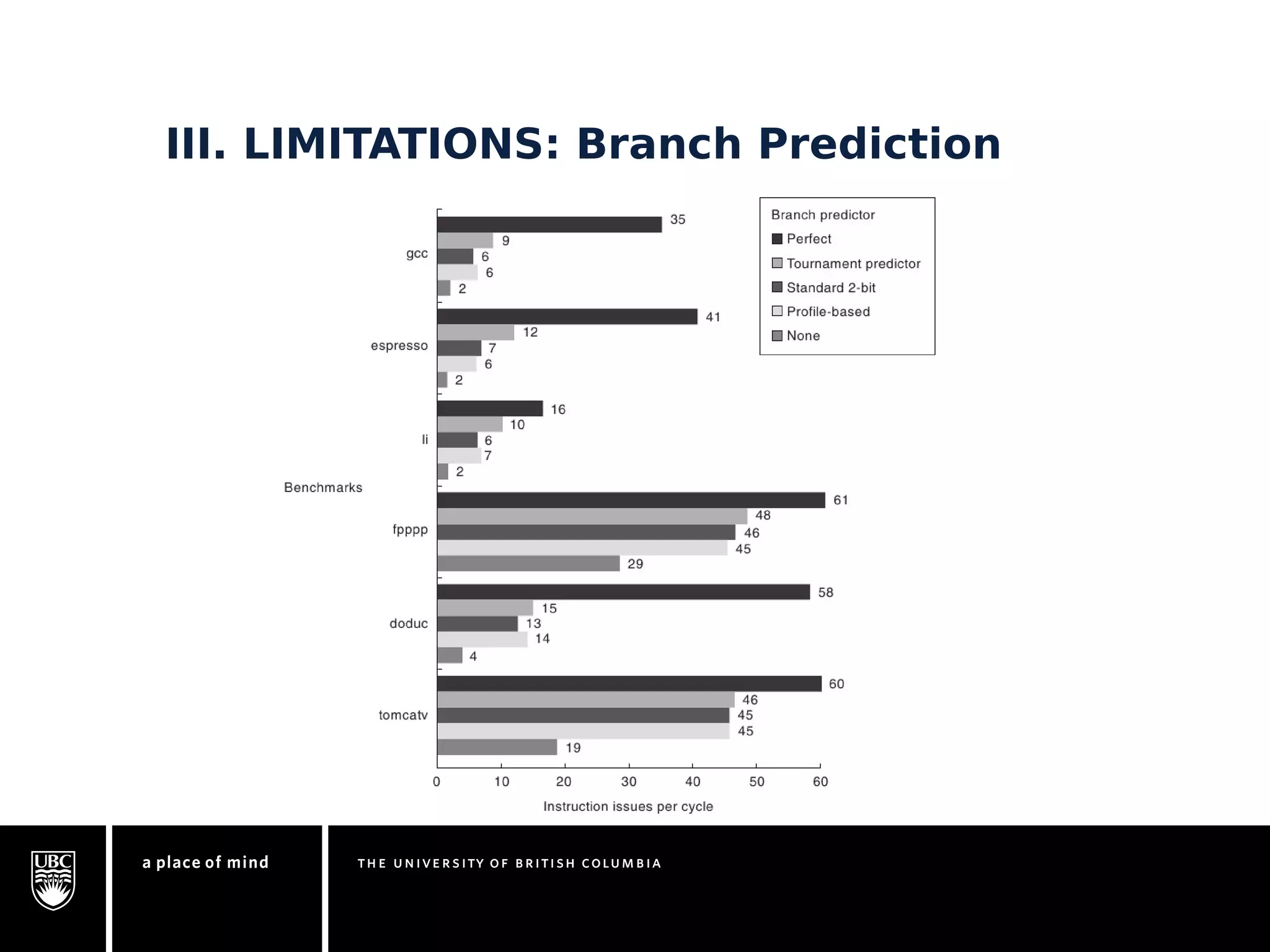

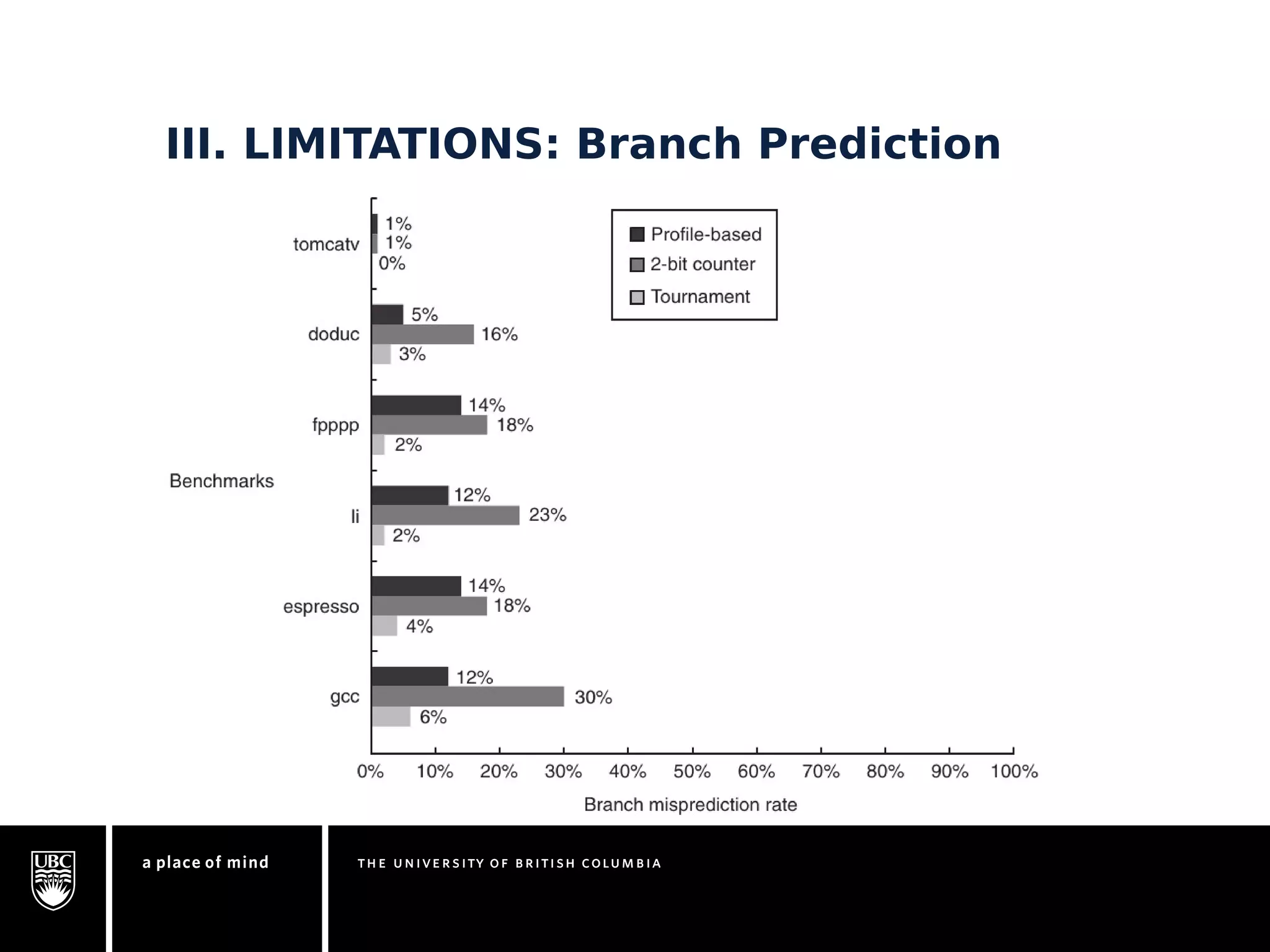

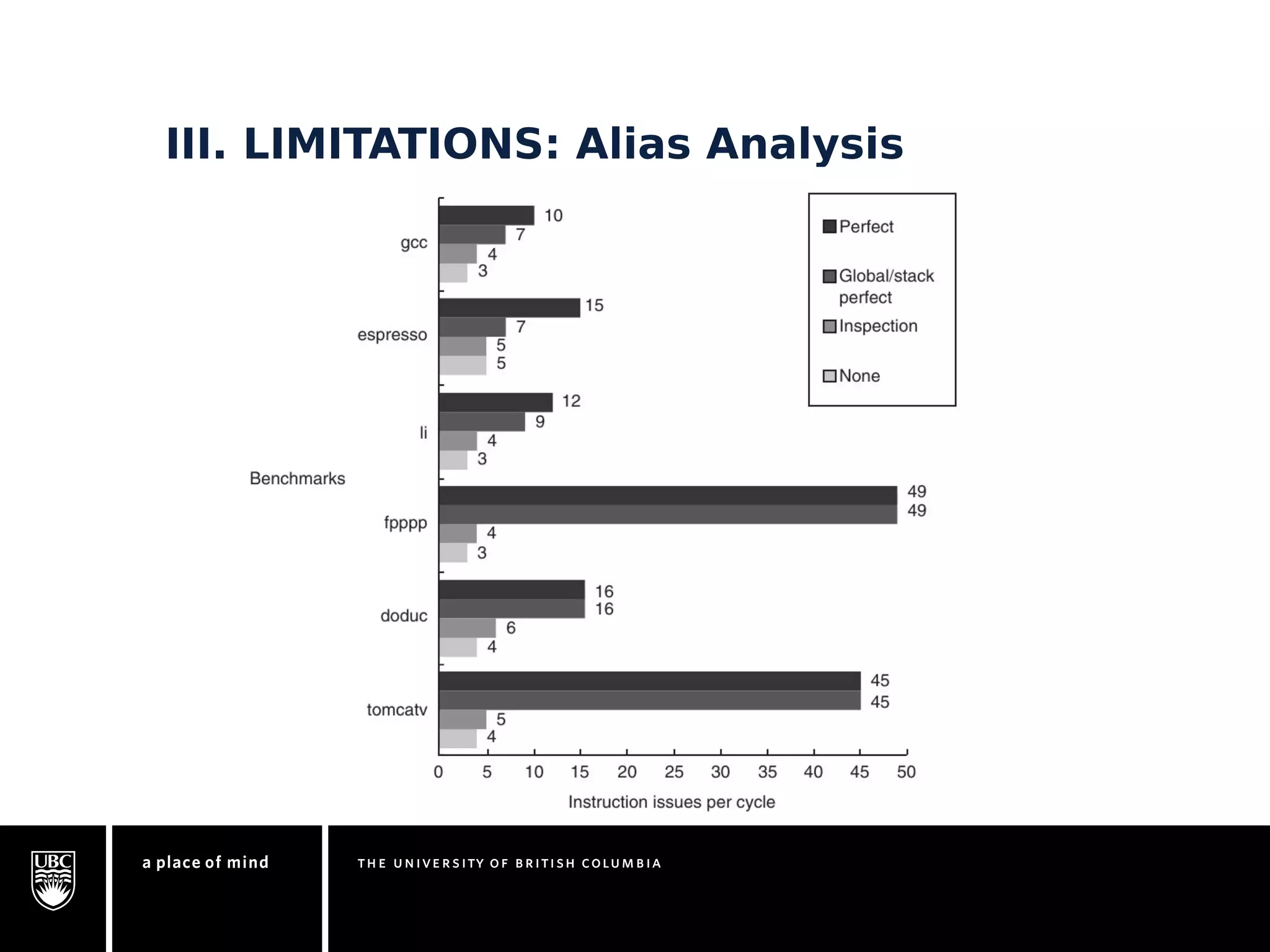

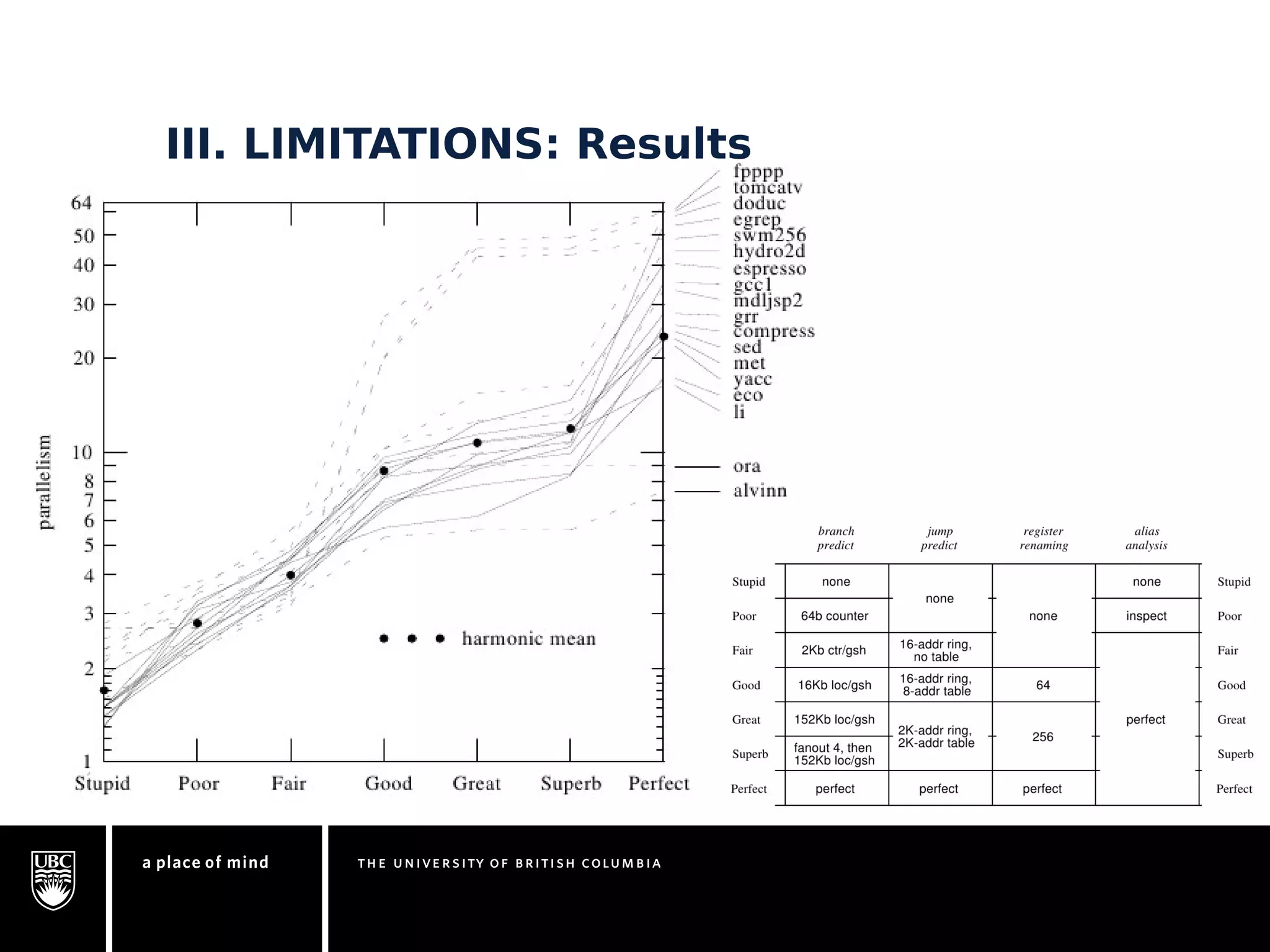

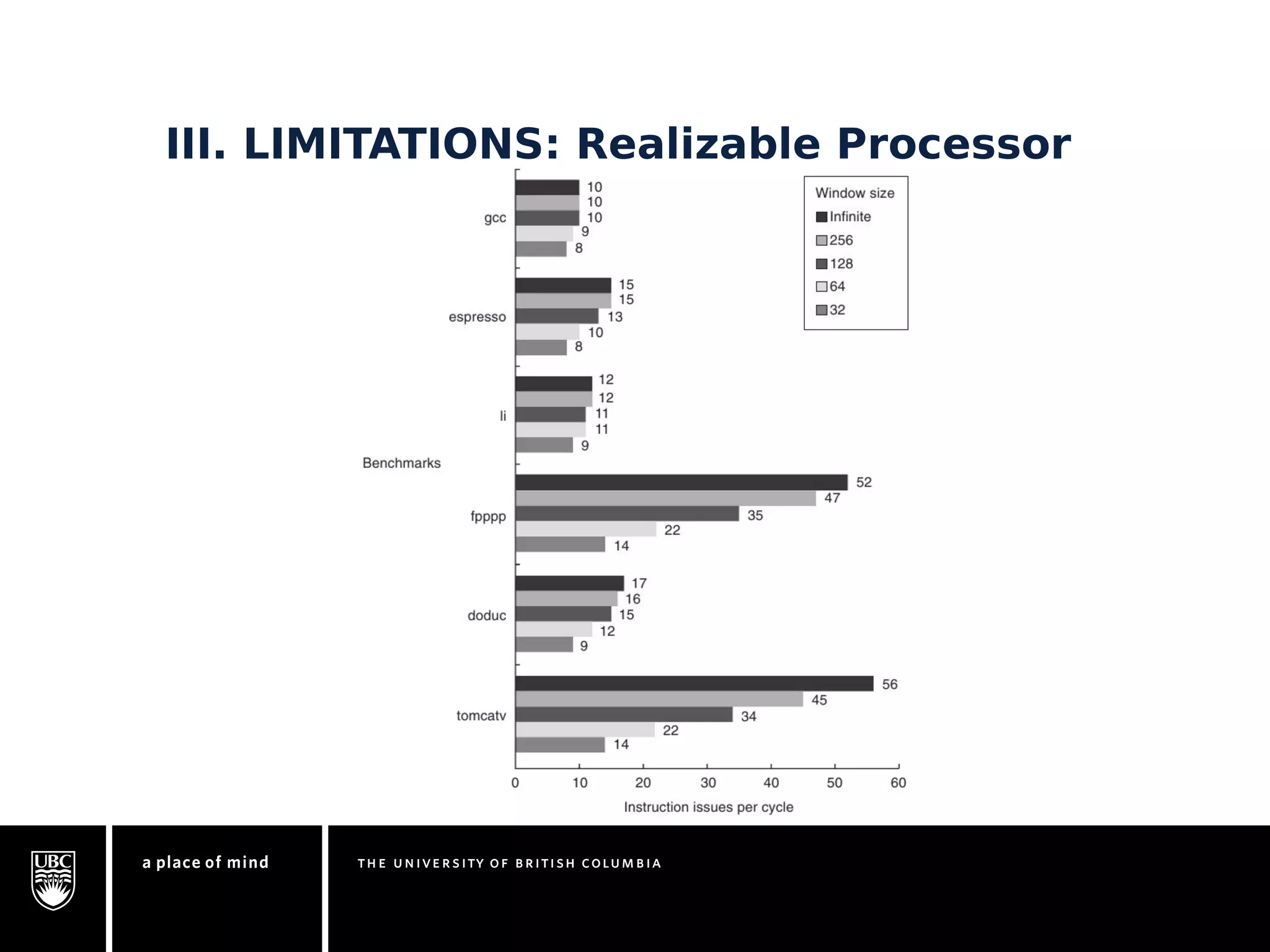

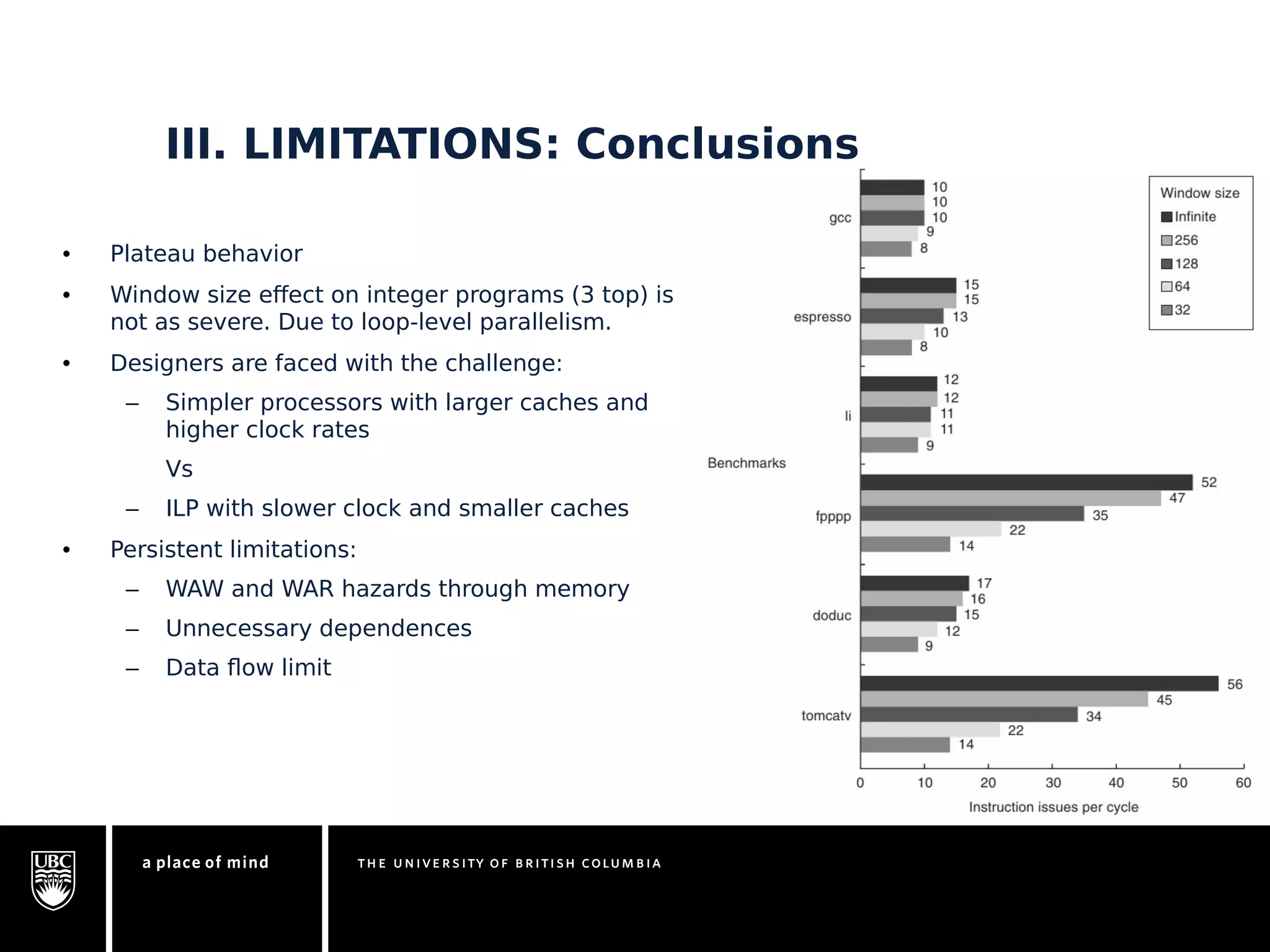

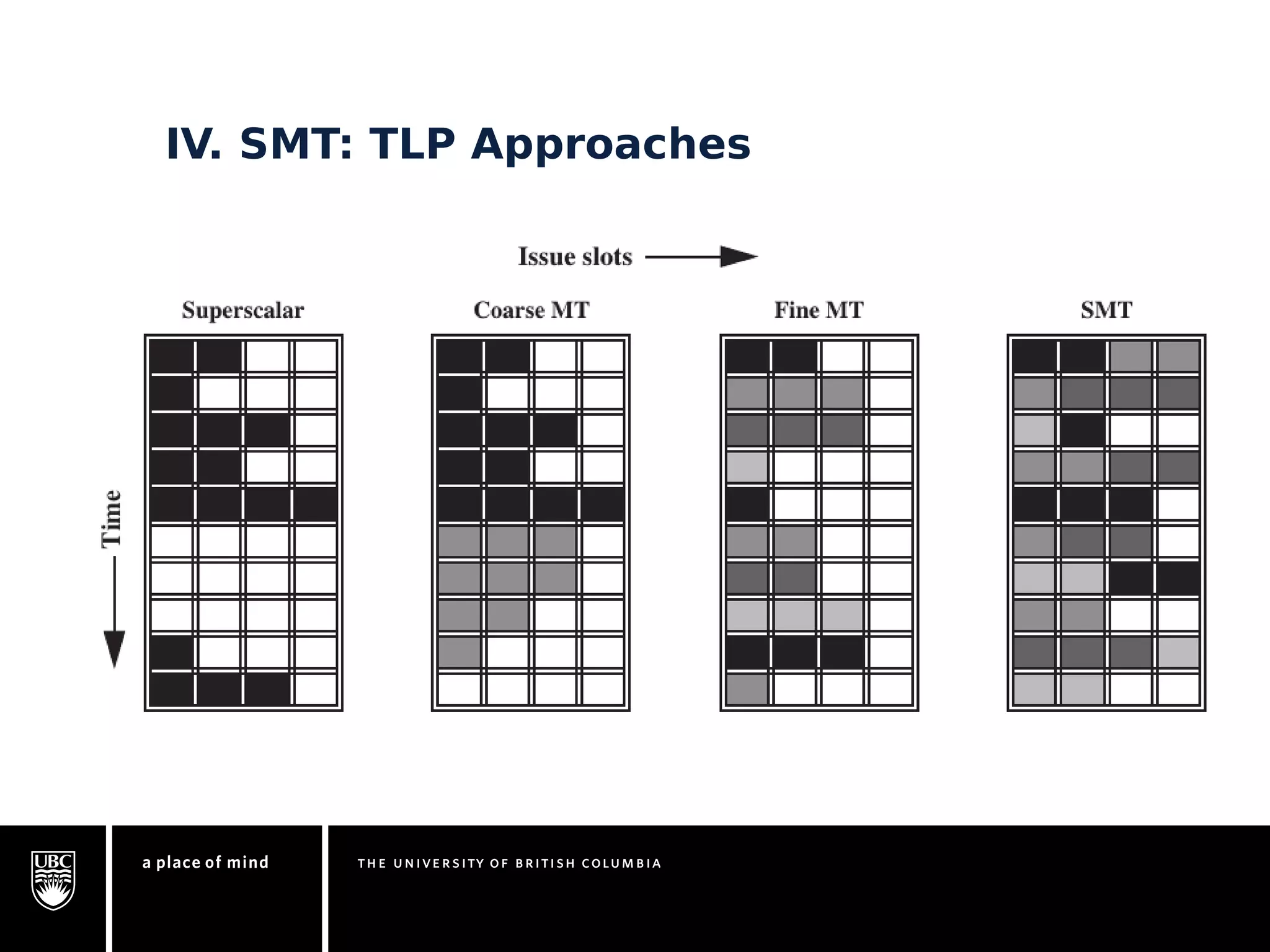

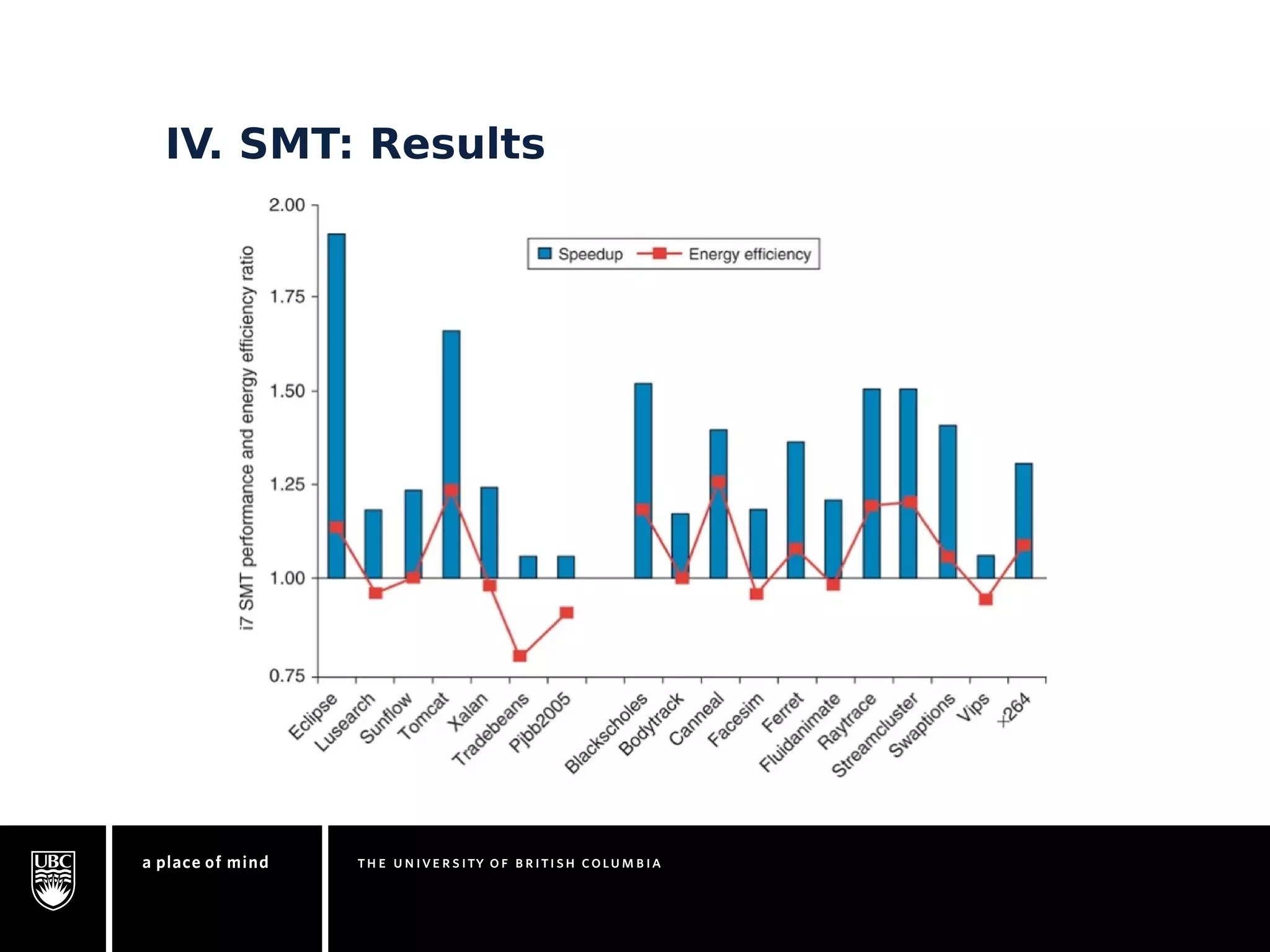

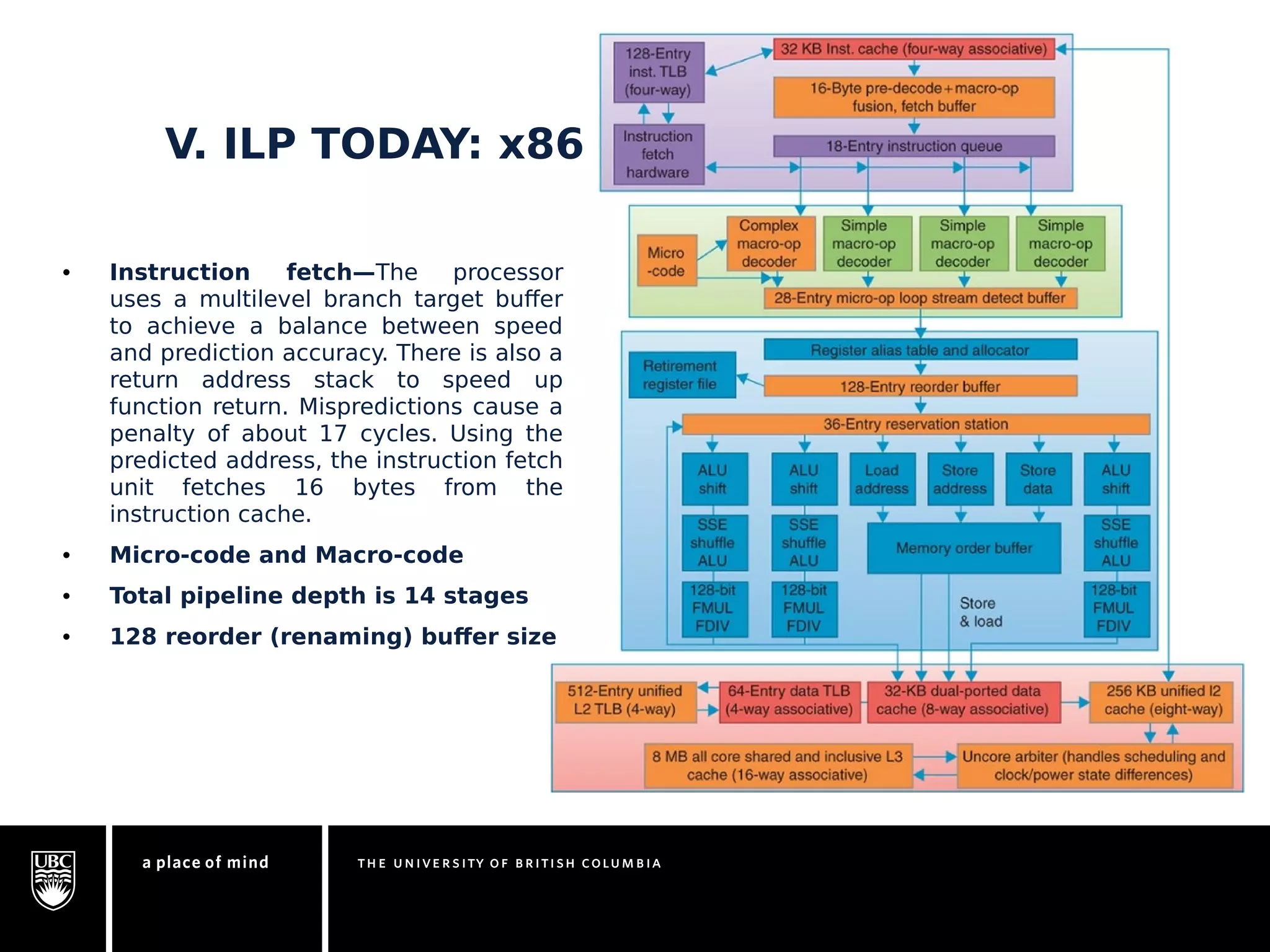

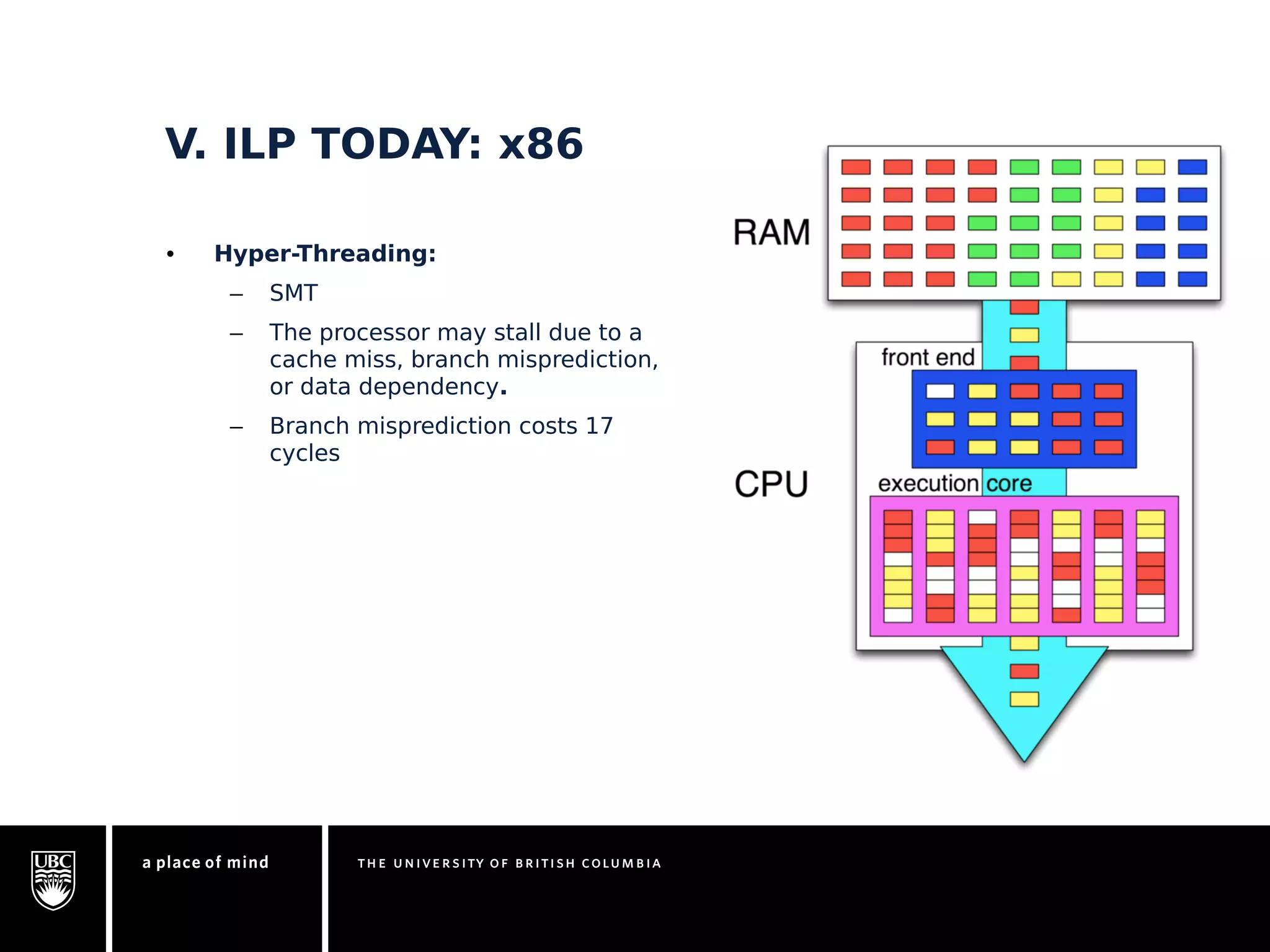

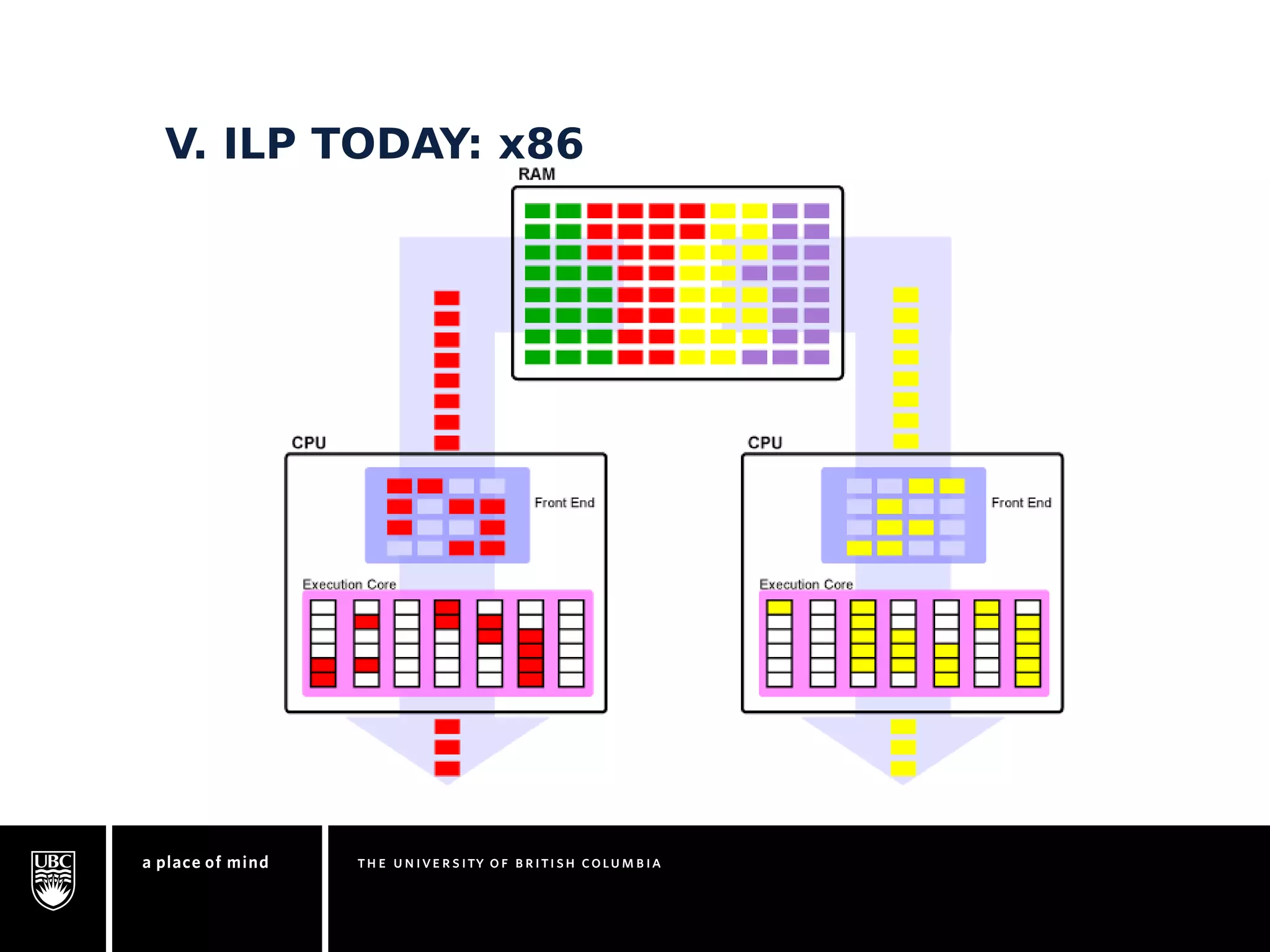

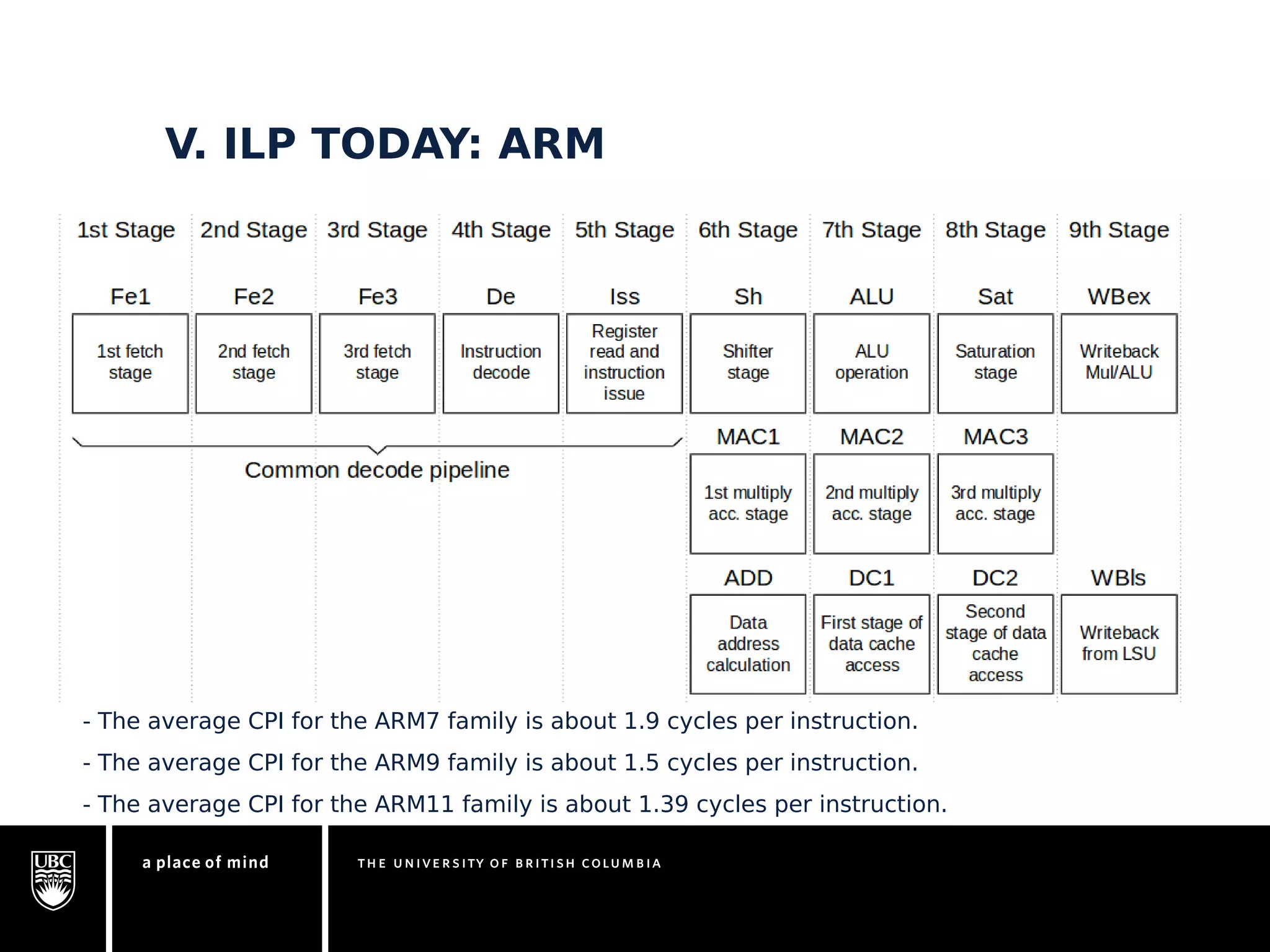

This document discusses instruction-level parallelism (ILP) limitations. It covers ILP background using a MIPS example, hardware models that were studied including register renaming and branch/jump prediction assumptions. A study of ILP limitations found diminishing returns with larger window sizes and realizable processors are limited by complexity and power constraints. Simultaneous multithreading was explored as a technique to improve ILP but has its own design challenges. Today, x86 and ARM processors employ various ILP optimizations within pipeline constraints.