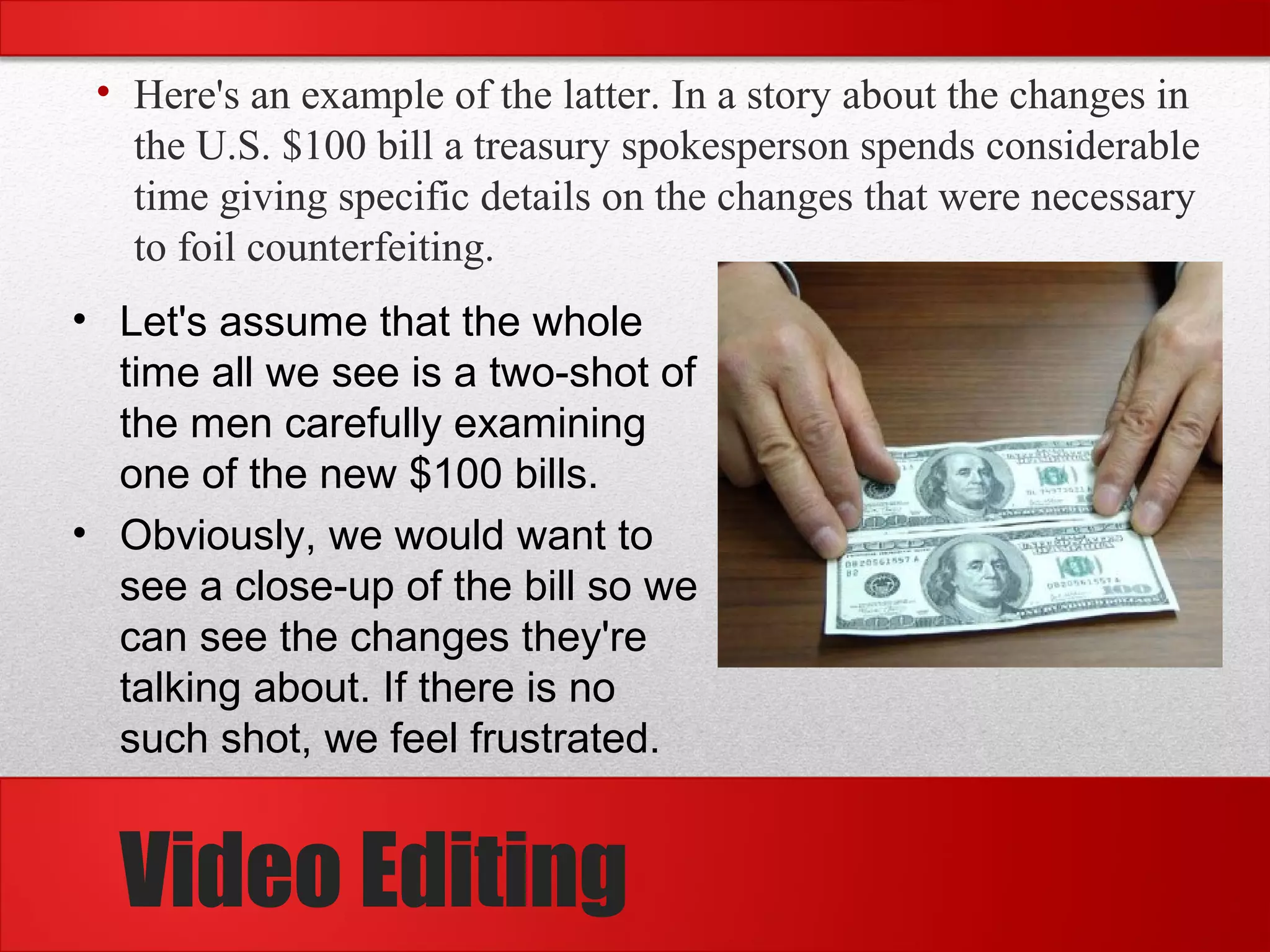

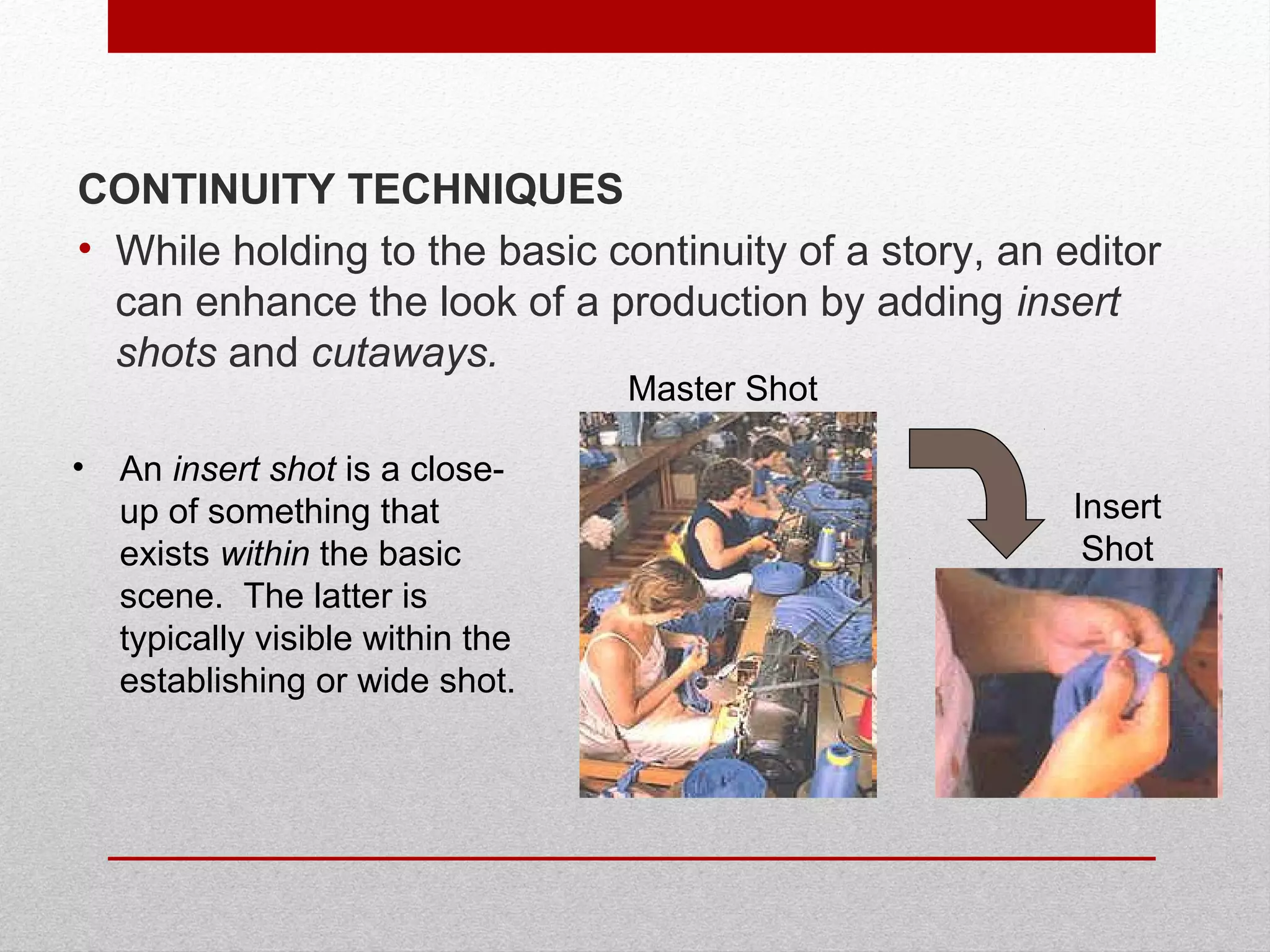

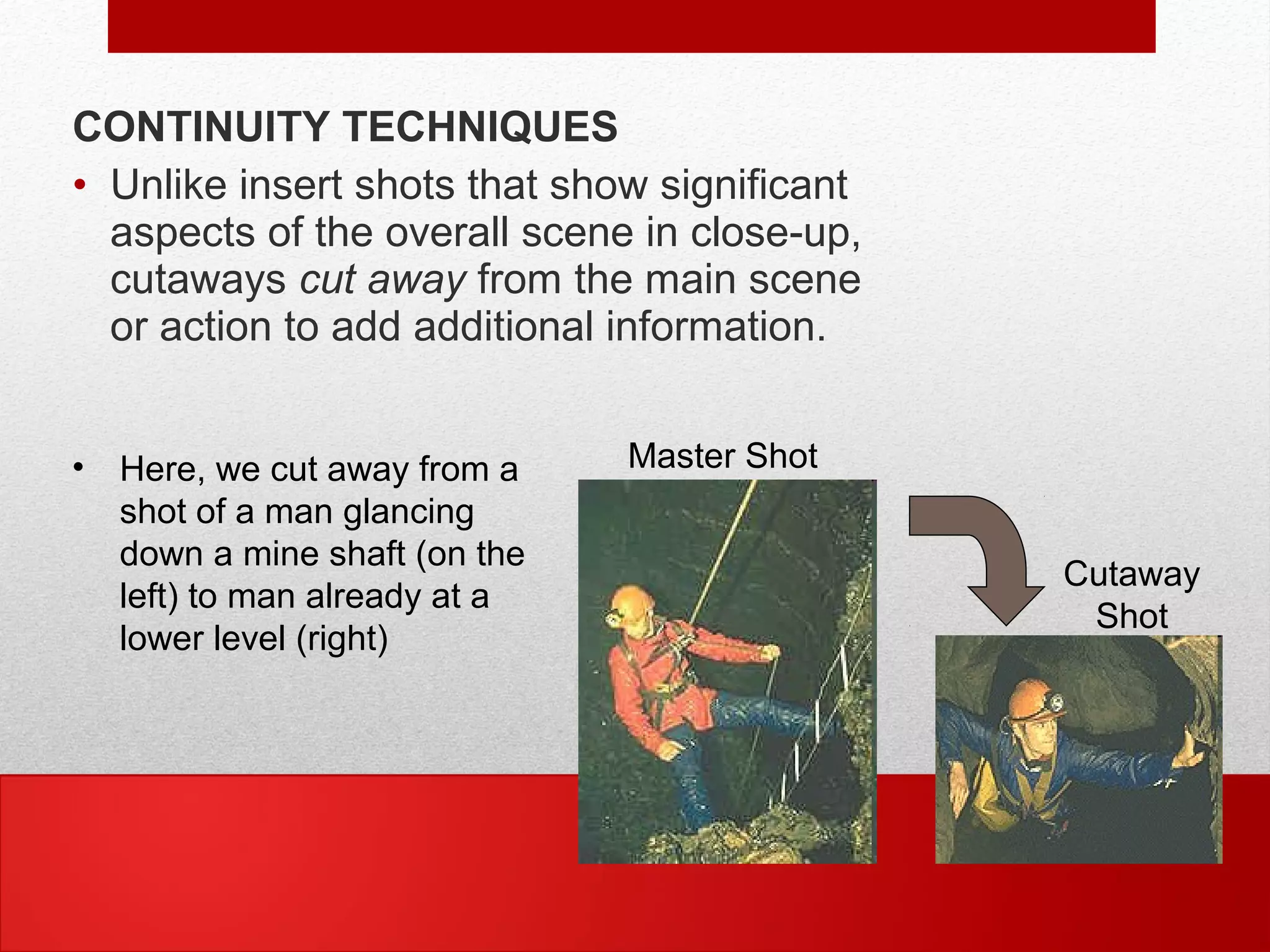

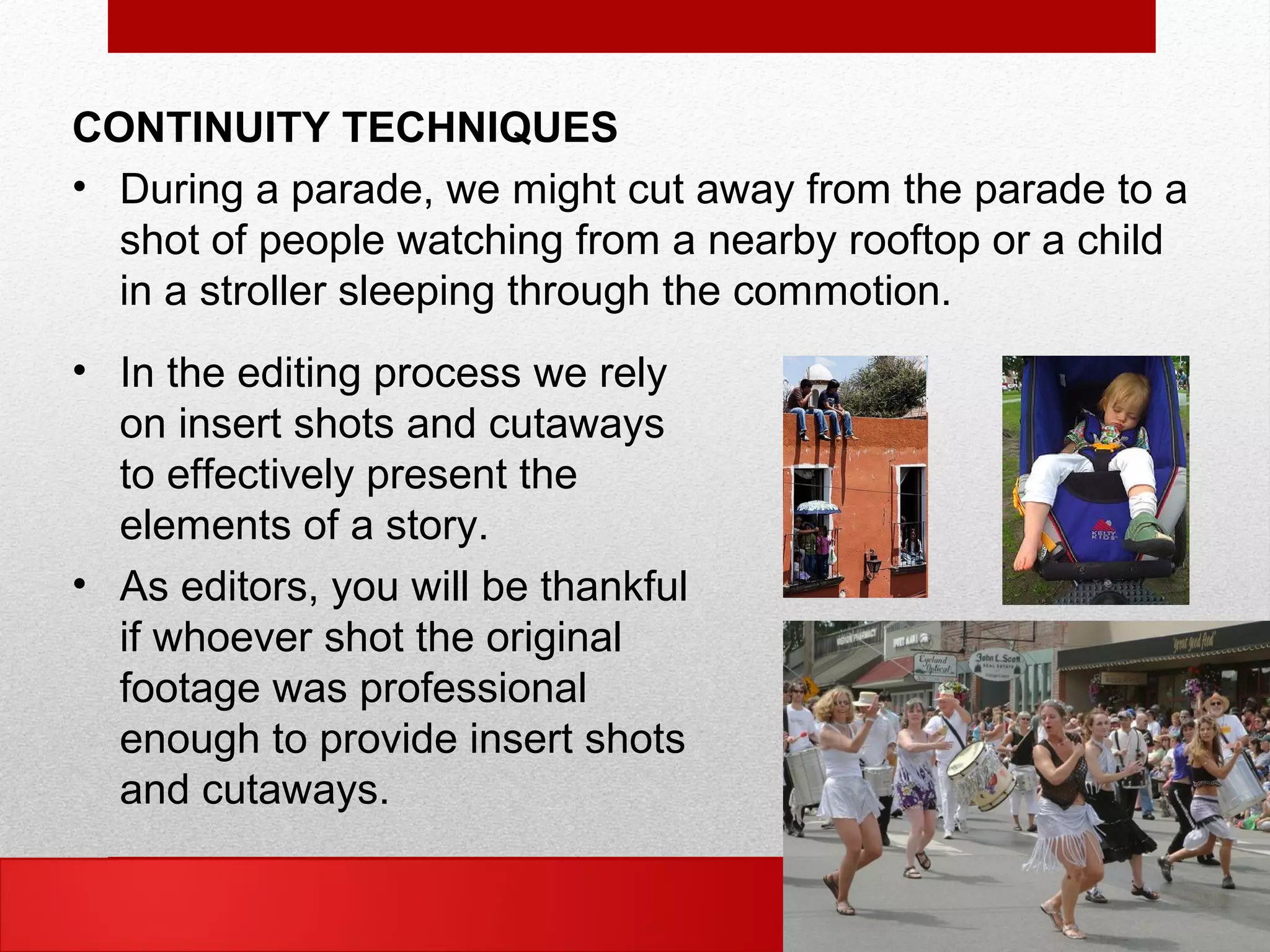

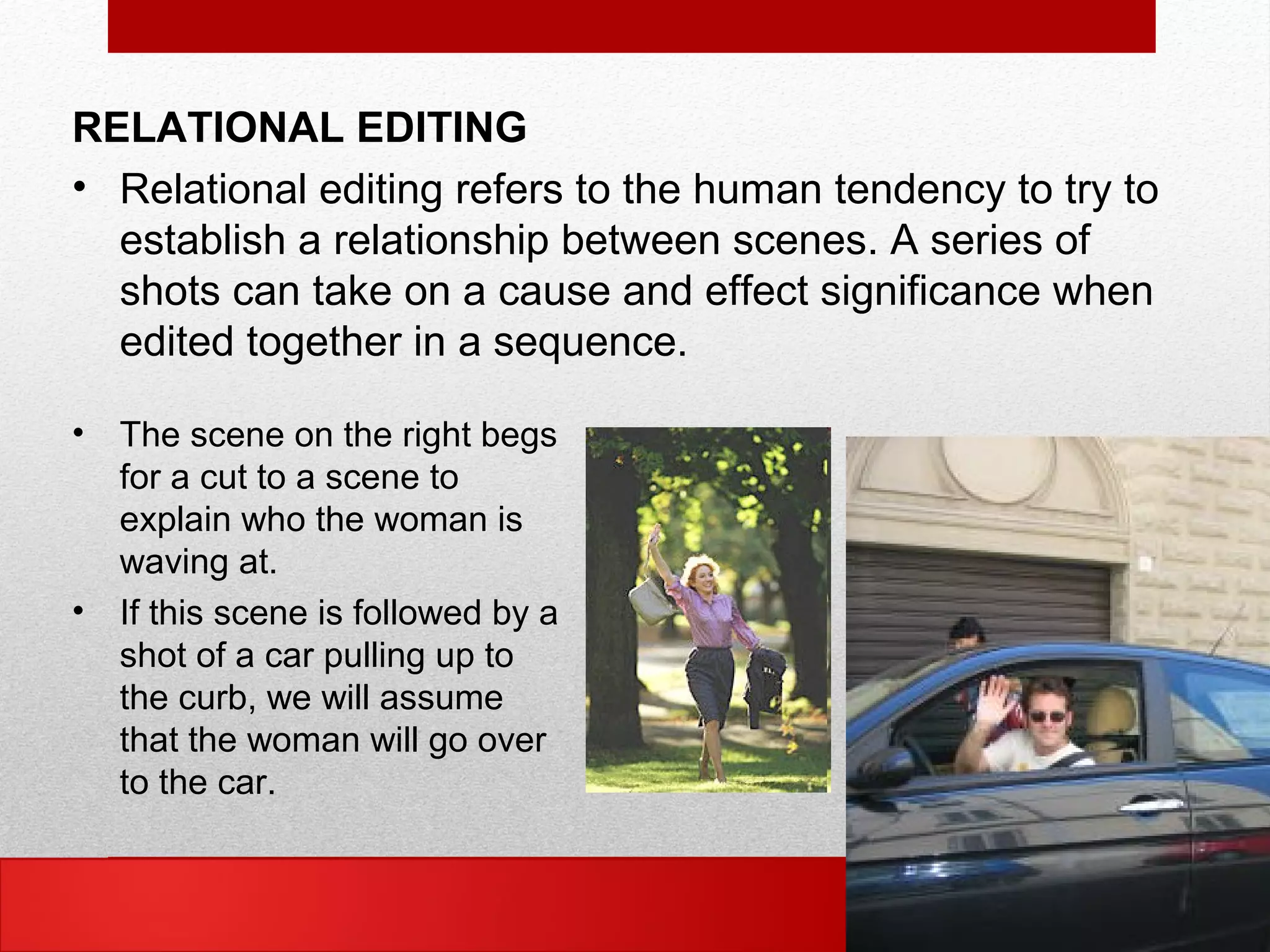

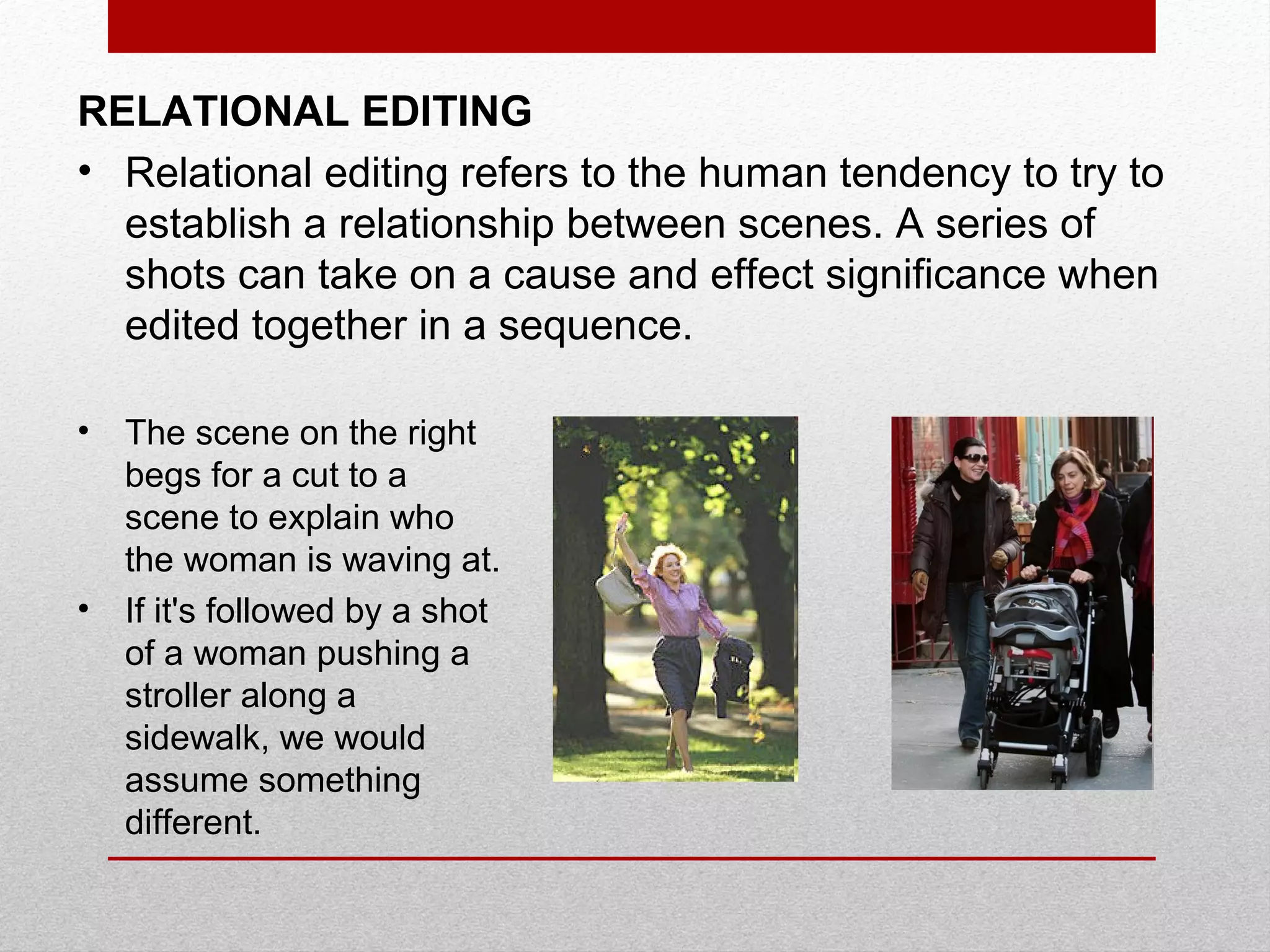

The document discusses various video editing techniques such as continuity editing, parallel cutting, and thematic editing. Continuity editing involves arranging shots in a logical sequence to suggest progression of events or cause and effect. Parallel cutting cuts between different storylines happening simultaneously to vary pace and heighten interest. Thematic editing rapidly cuts between shots based on a central theme rather than a logical narrative. Proper use of techniques like insert shots, cutaways, and exploring motivation can enhance storytelling and believability.