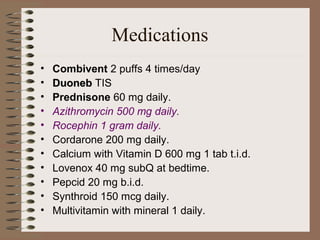

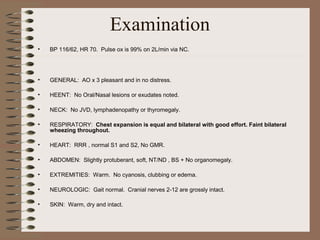

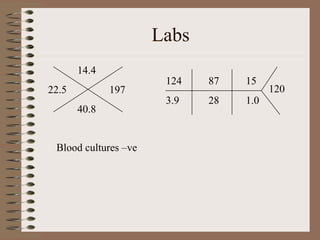

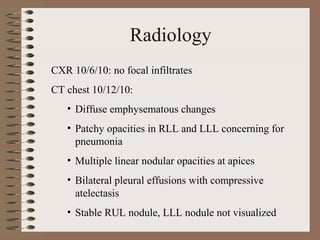

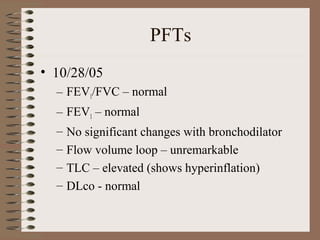

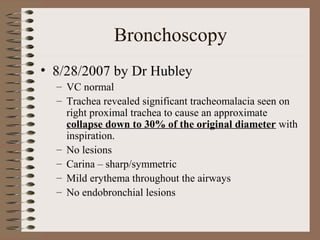

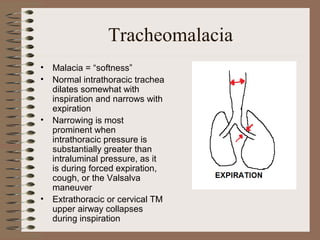

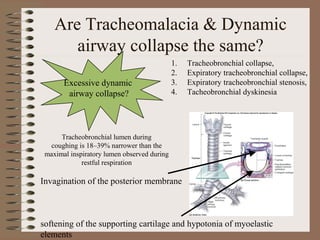

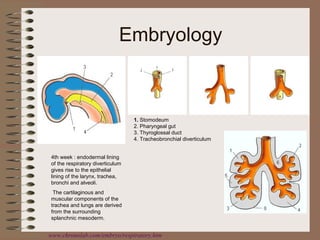

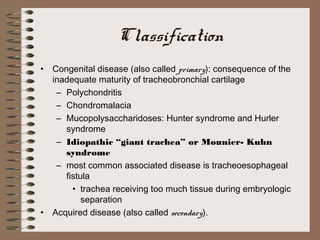

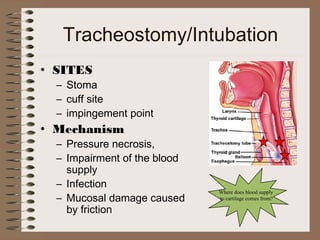

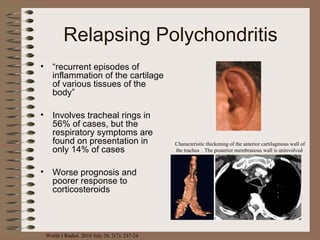

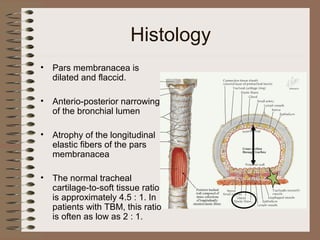

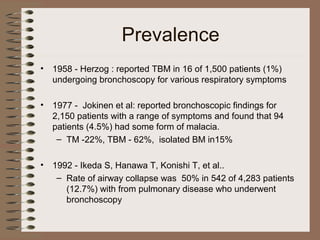

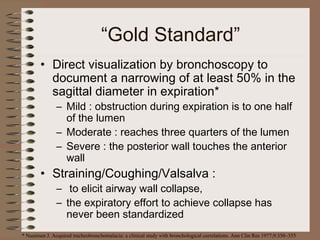

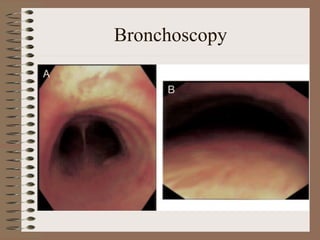

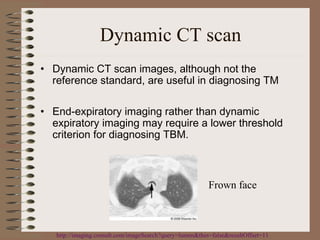

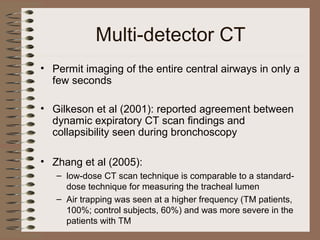

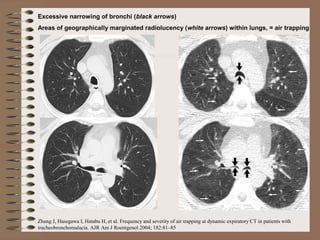

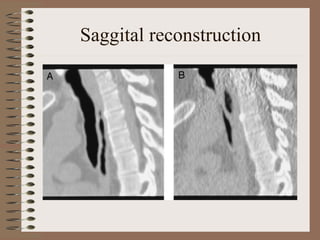

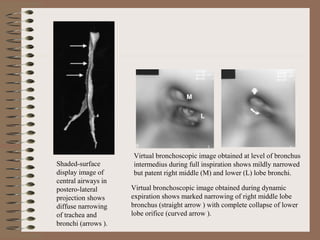

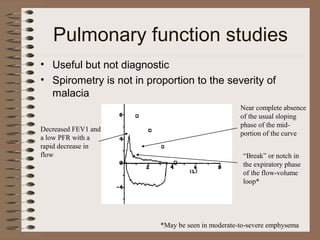

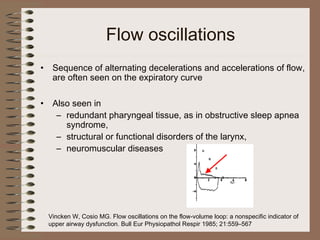

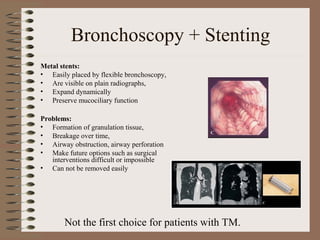

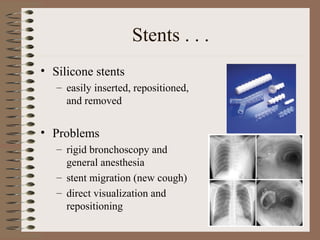

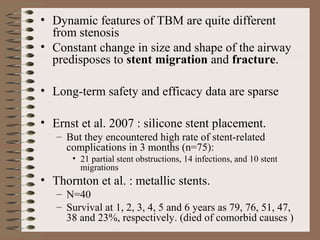

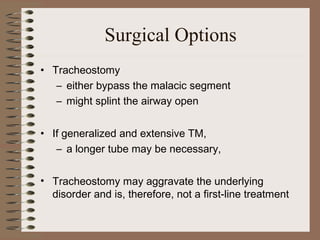

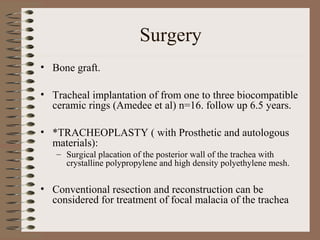

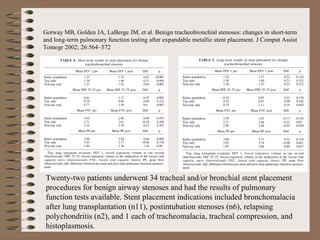

This clinical case conference document discusses a 95-year-old male patient presenting with progressive shortness of breath. It provides details on the patient's medical history including prior treatment for Mycobacterium avium complex and tracheomalacia. The document summarizes examination findings and test results. It also includes an in-depth discussion of tracheomalacia including classification, causes, symptoms, diagnostic methods such as bronchoscopy, imaging with CT and MRI, and treatment challenges for this condition.