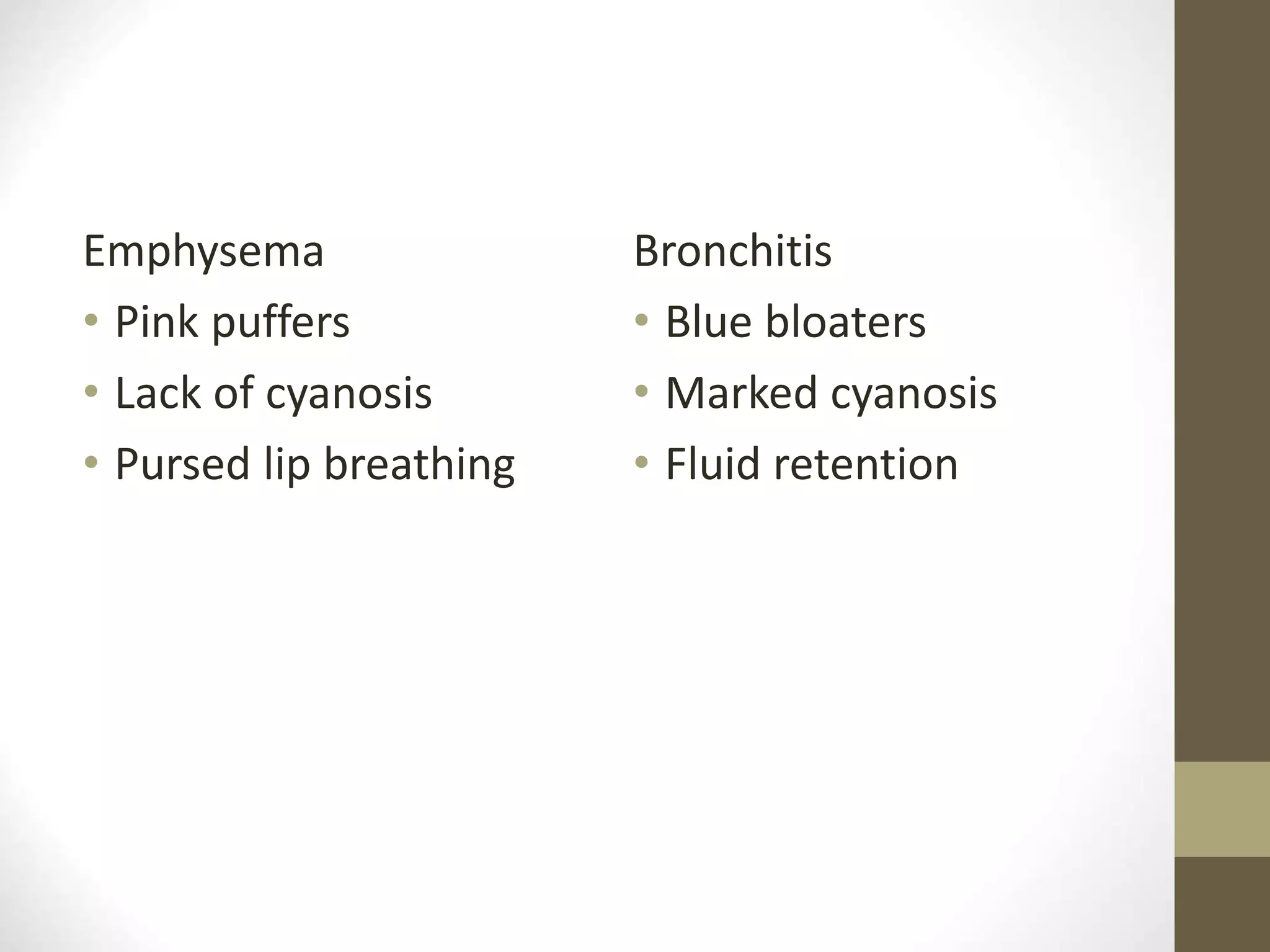

COPD is a chronic lung disease characterized by persistent airflow limitation that is usually progressive. It is caused by exposure to noxious particles or gases, most commonly from cigarette smoking. The major pathological changes include inflammation in the small airways and destruction of the lung parenchyma (emphysema). Symptoms typically include cough, sputum production, and shortness of breath. Diagnosis is confirmed by spirometry showing airflow obstruction that is not fully reversible with bronchodilators. Treatment focuses on smoking cessation, vaccinations, bronchodilators, and management of exacerbations with antibiotics and corticosteroids.