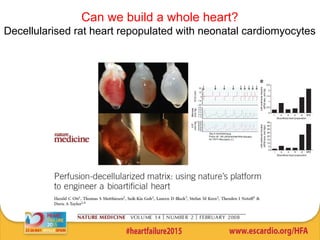

This document summarizes research on tissue engineering approaches for treating heart and valve failure. It discusses developing cardiac patches made of biomaterials seeded with cells, testing patches in animal models, and evaluating function. Heart valve engineering using scaffolds seeded with human cells is also reviewed. Whole heart engineering by decellularizing and repopulating rat hearts is presented. Clinical perspectives are discussed, such as enrolling patients for efficacy tests of engineered myocardial tissue and assessing safety issues. The goal is developing tissue engineering therapies for treating unmet clinical needs in heart disease.