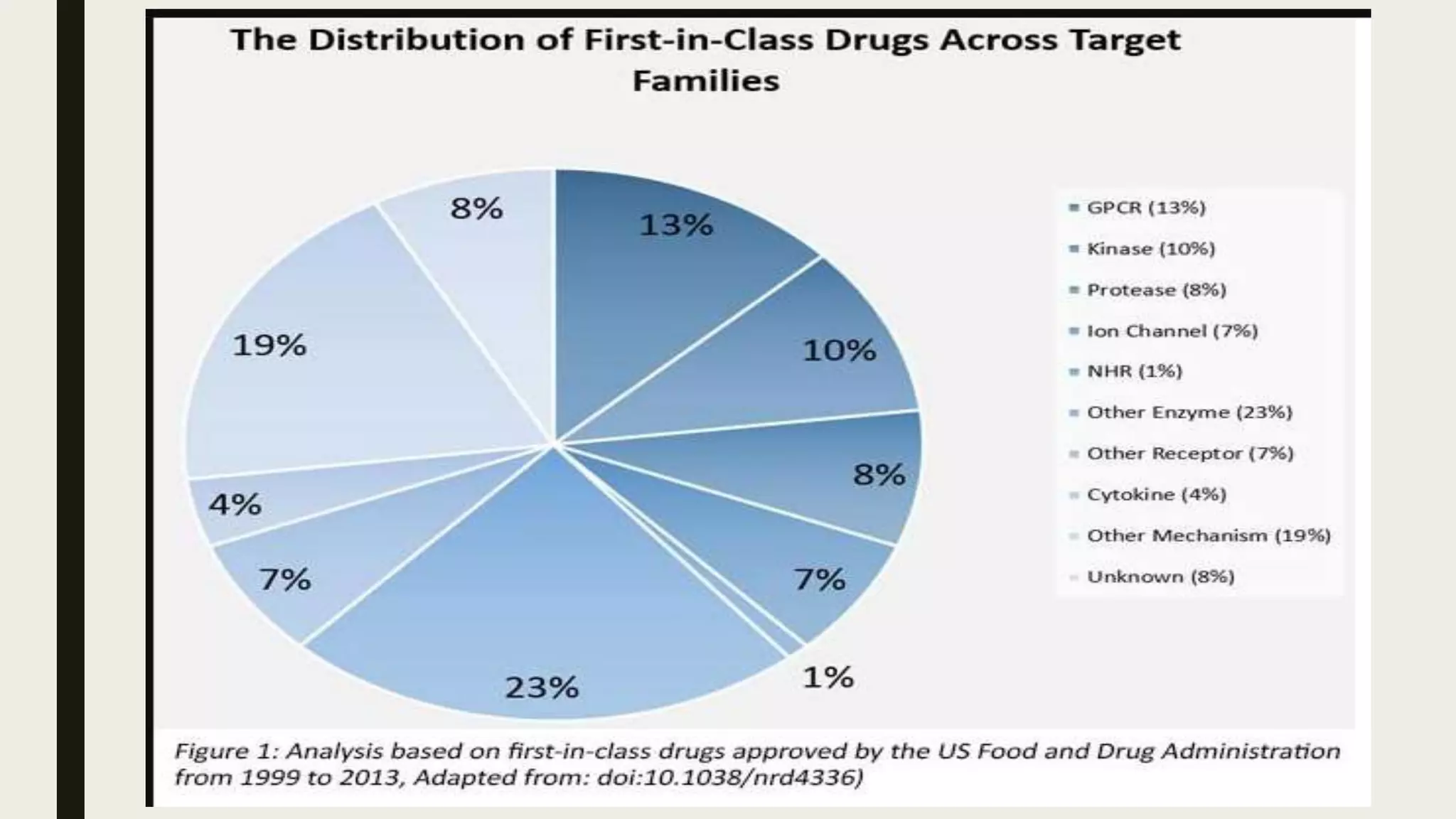

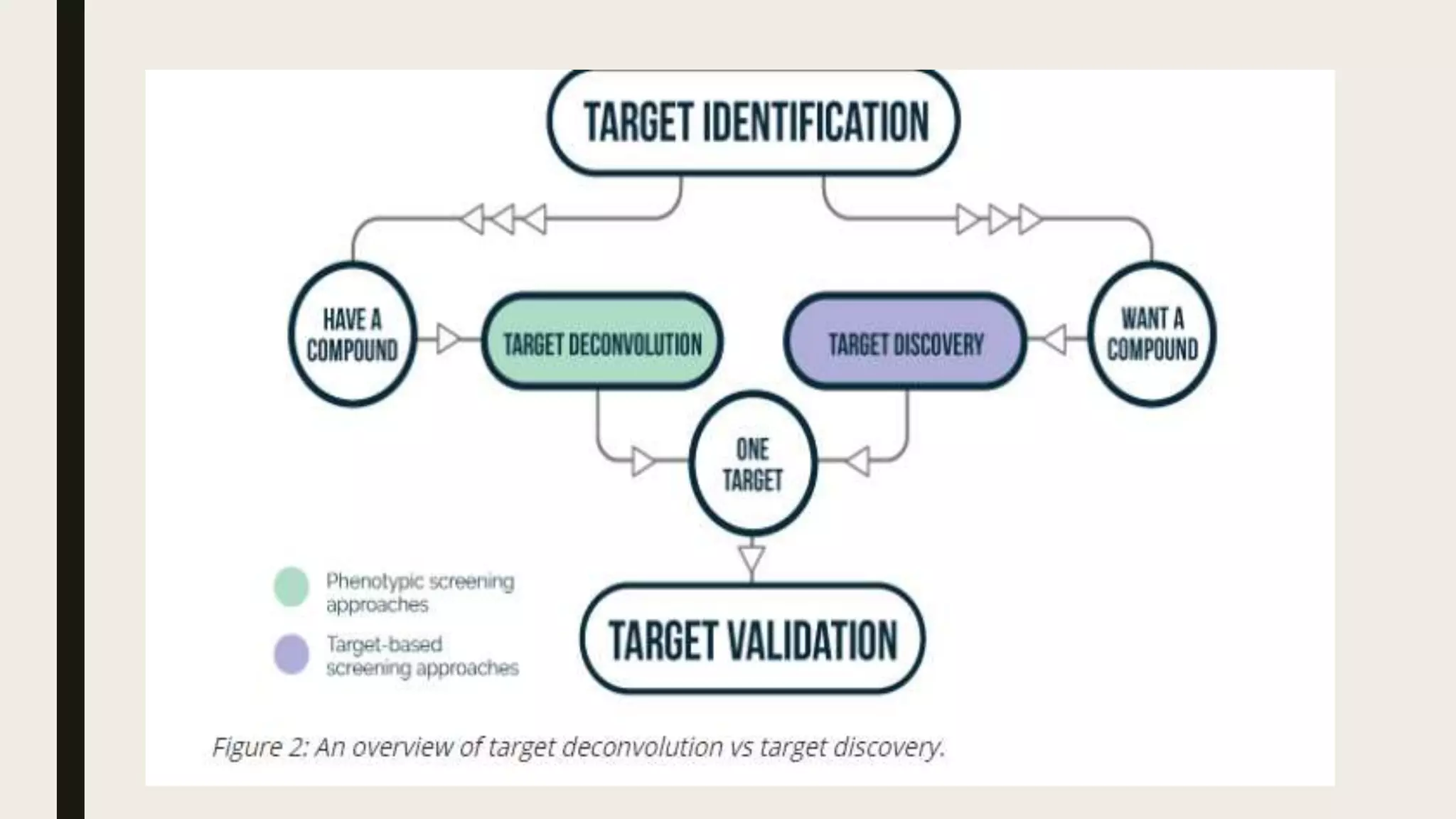

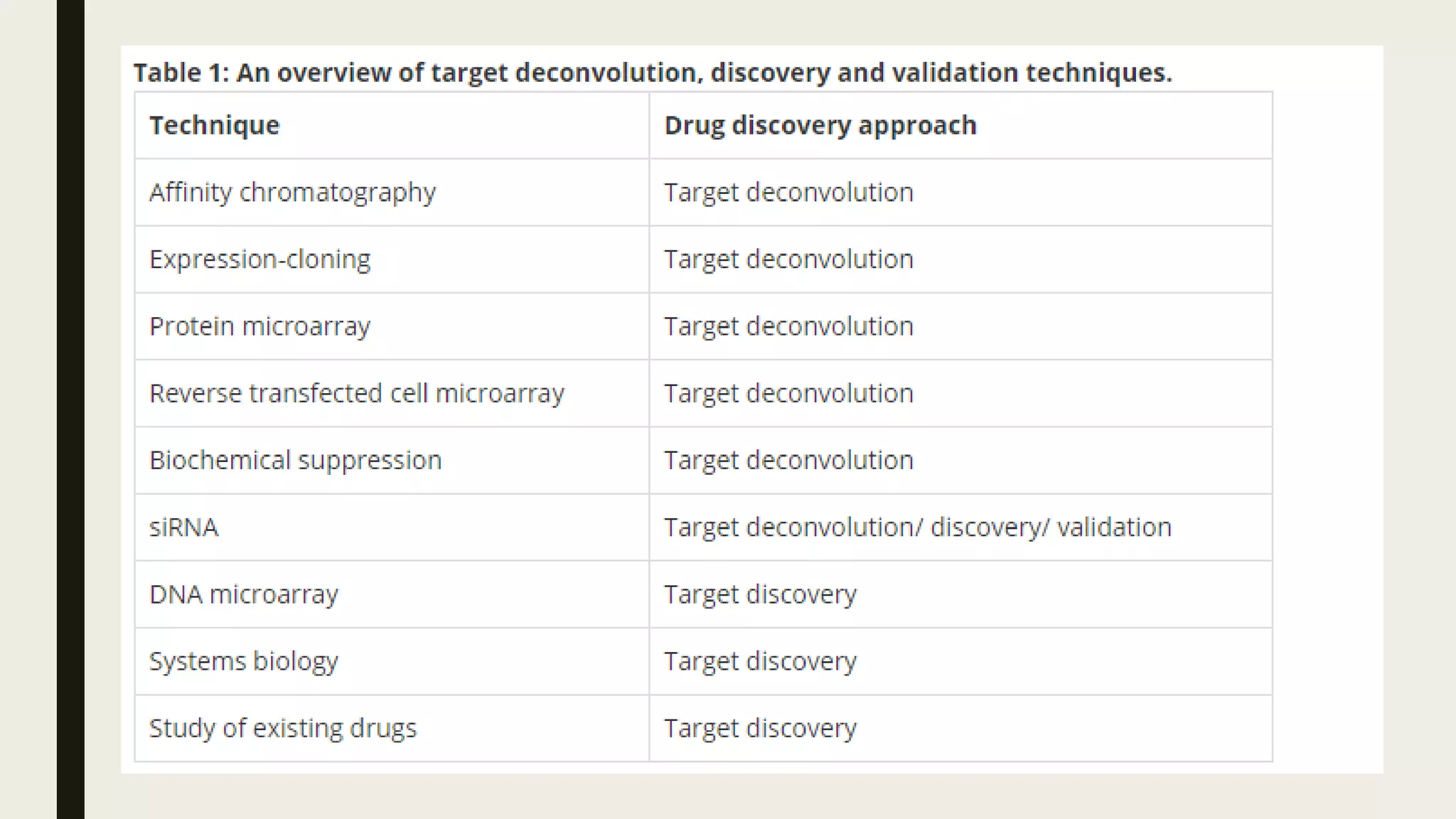

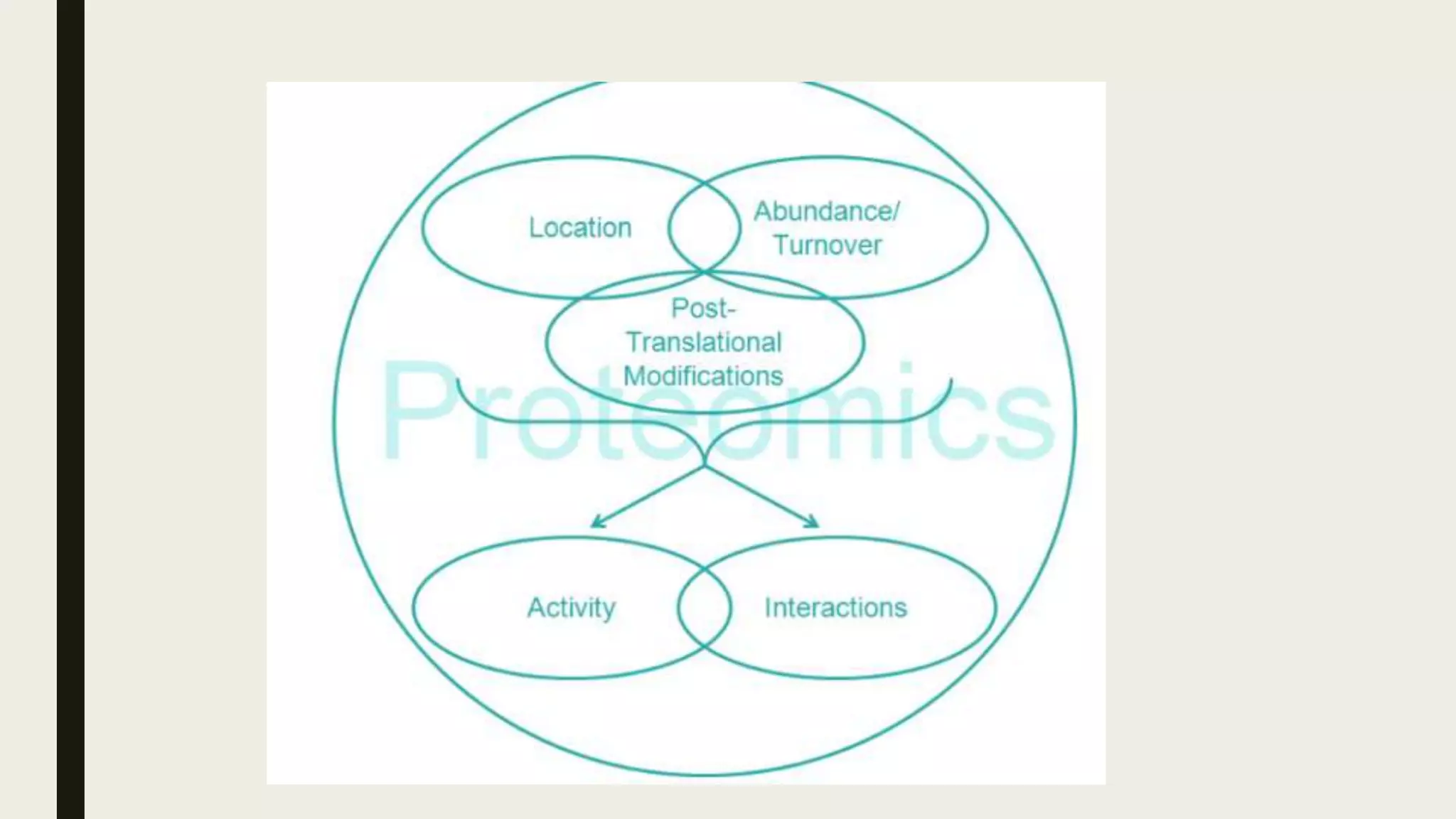

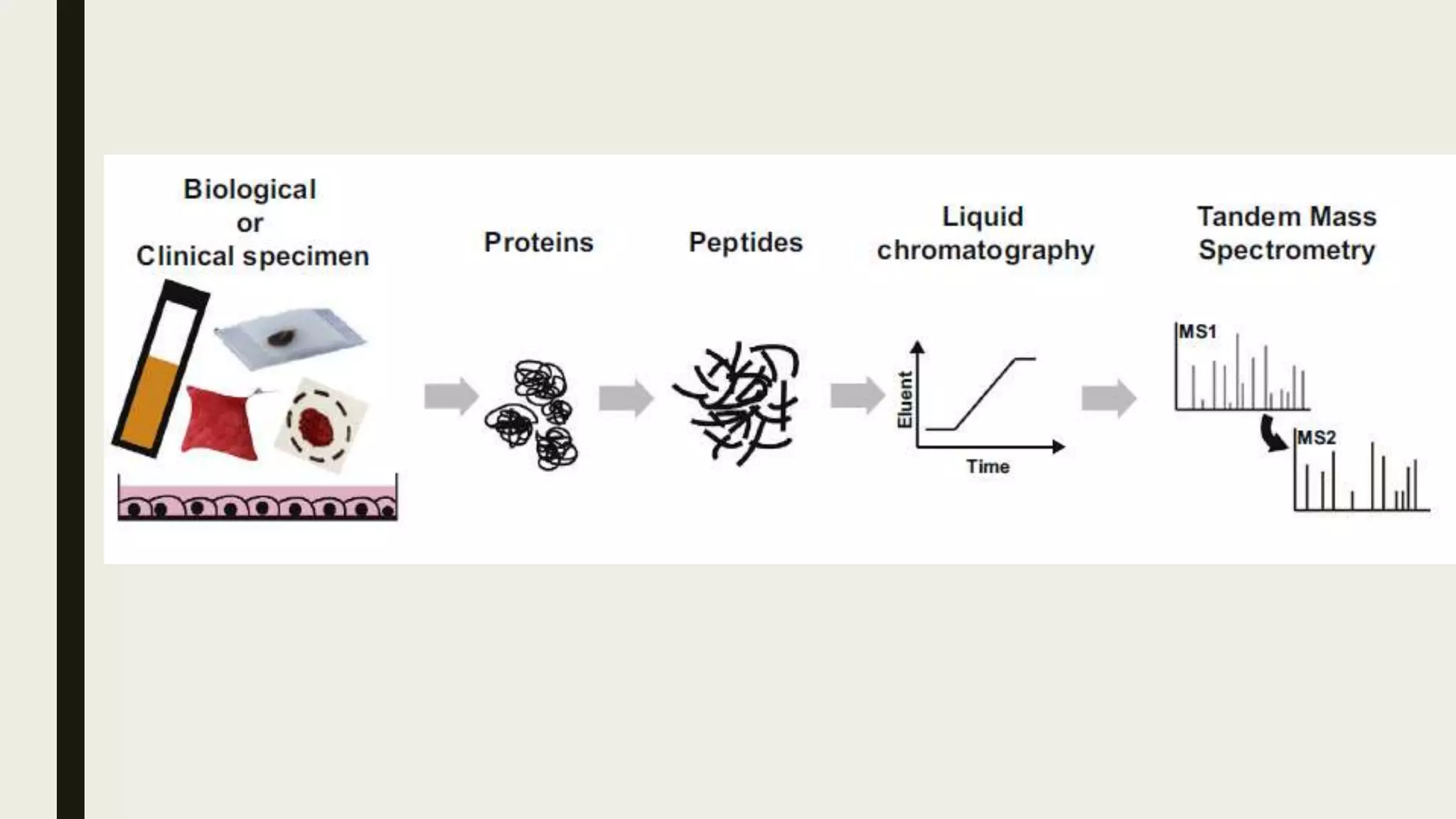

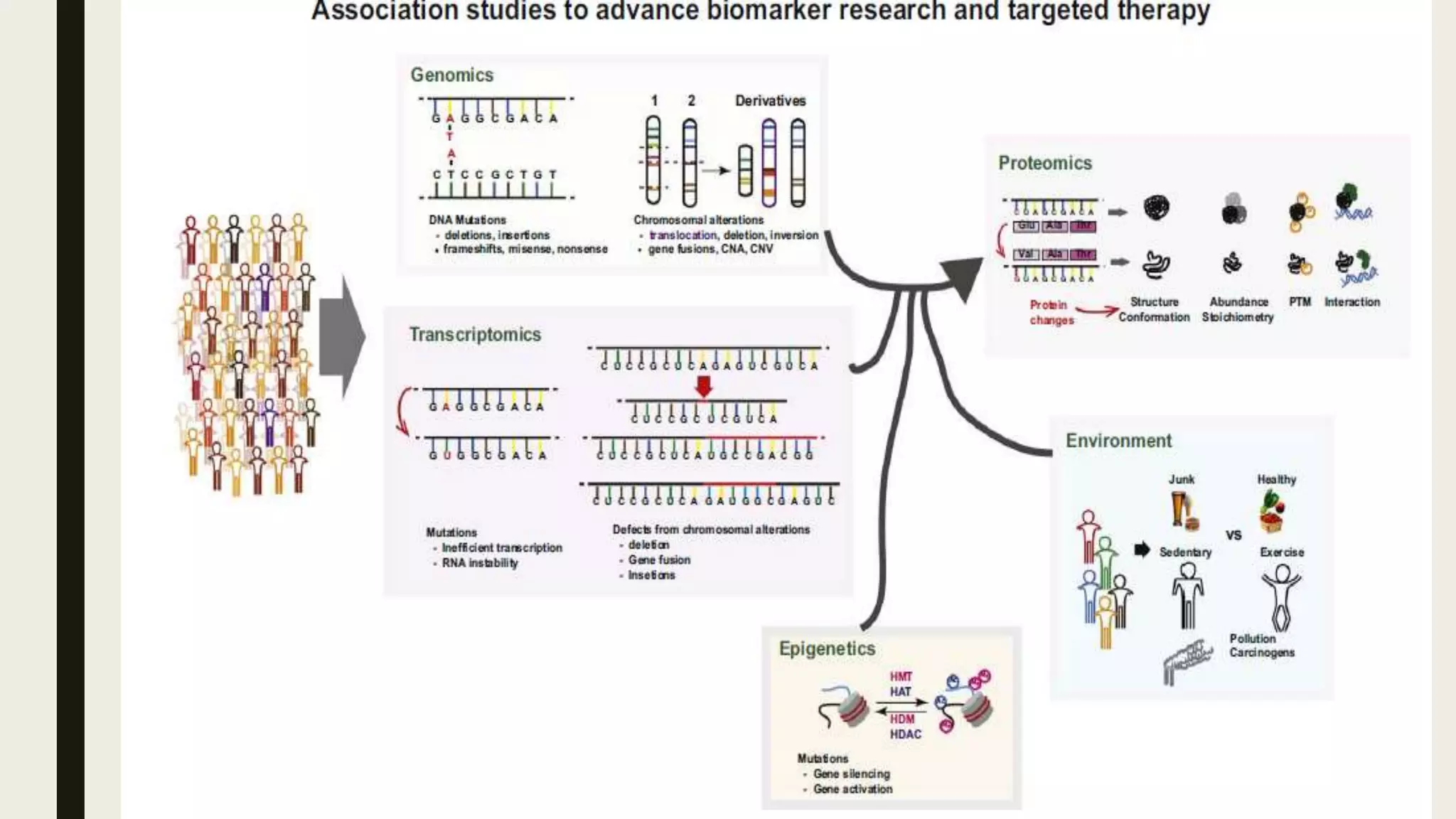

The document discusses the processes of target discovery and validation in drug development, highlighting the roles of proteomics in identifying and validating drug targets. It emphasizes the importance of understanding protein functions, interactions, and the complexities of the proteome in relation to disease phenotypes, as well as the challenges in proteomic technology. Key concepts include distinguishing between target discovery and deconvolution, the significance of reproducibility in target validation, and the advancements in proteomic methods for drug target identification.