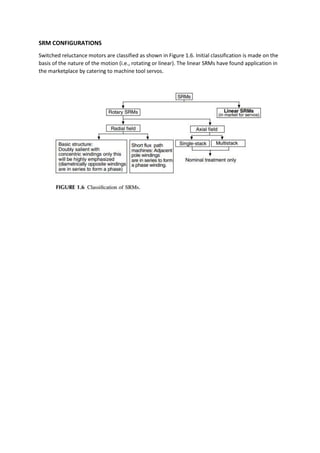

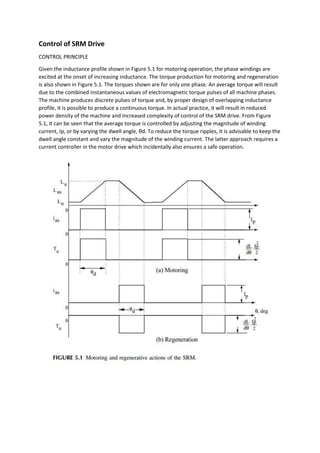

The document discusses switched reluctance motors (SRMs). It provides information on the working principle, elementary operation, inductance profiles, configurations, selection of phases, converter configurations, control, sensorless operation, and applications of SRMs. Key points include that SRMs operate based on variable reluctance torque, power is transmitted through stator windings rather than the rotor, and proper control of current timing and magnitude can produce smooth torque from discrete pulses. SRMs are applicable where size and power-to-weight ratio are critical factors.