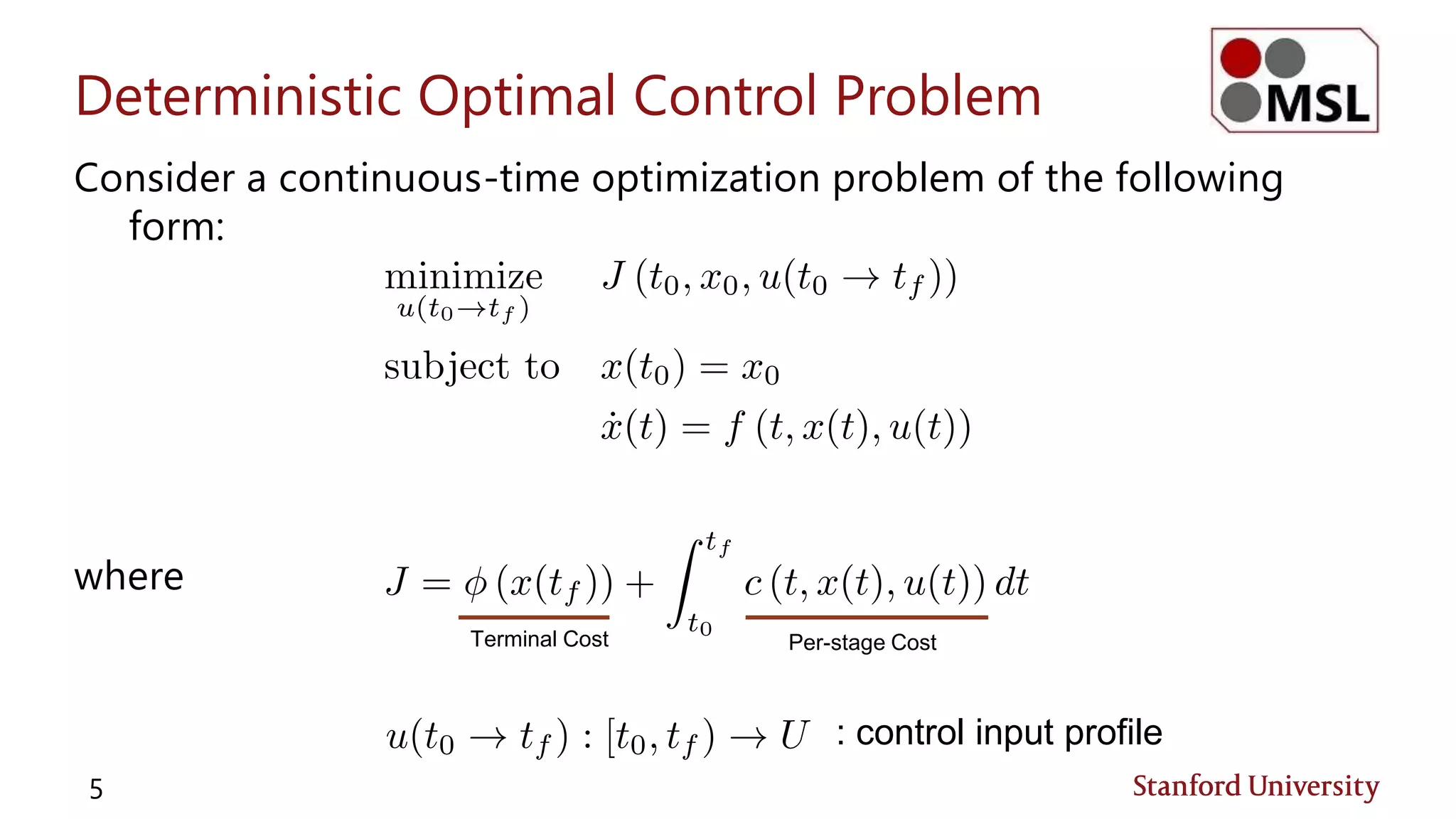

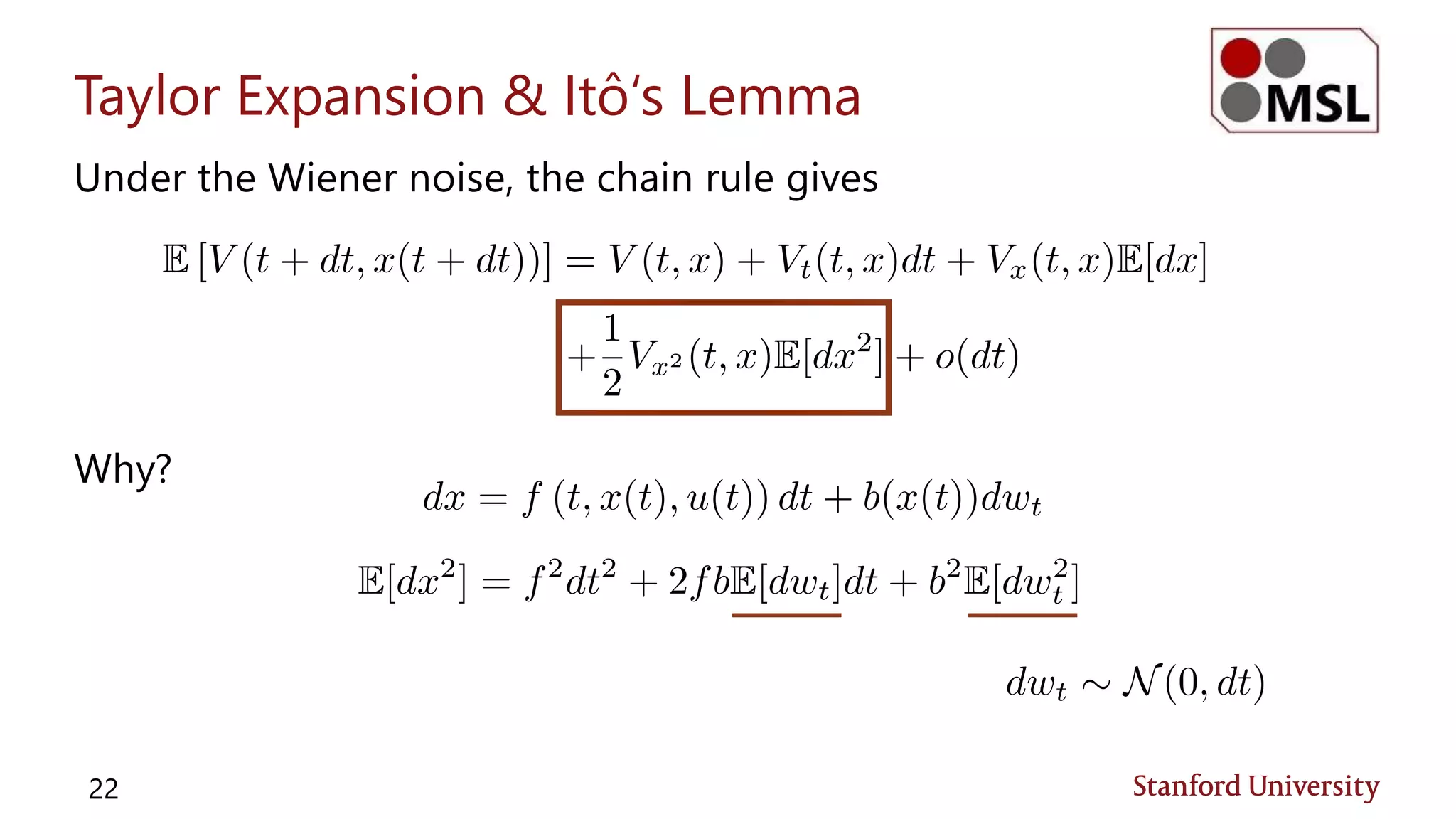

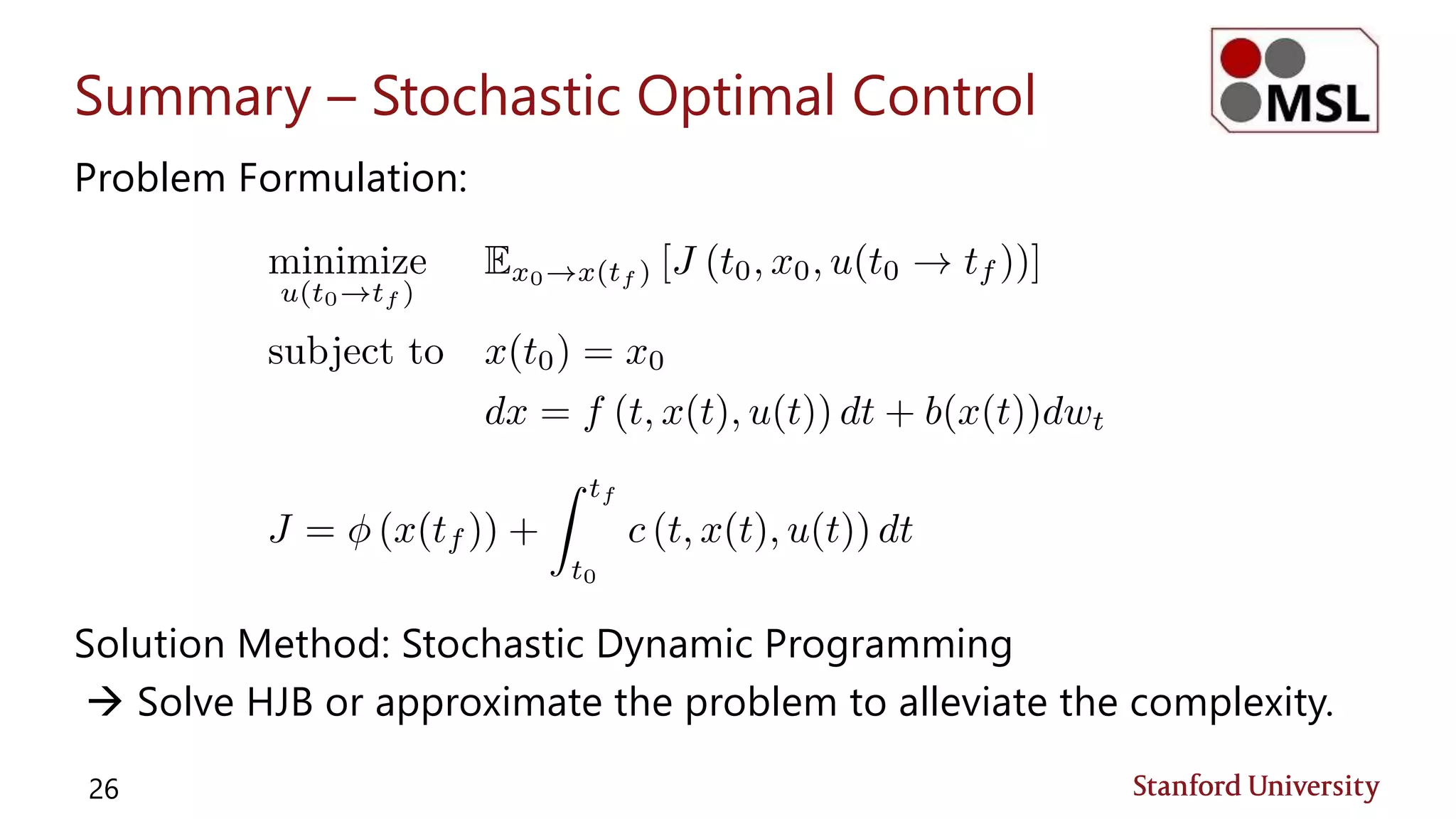

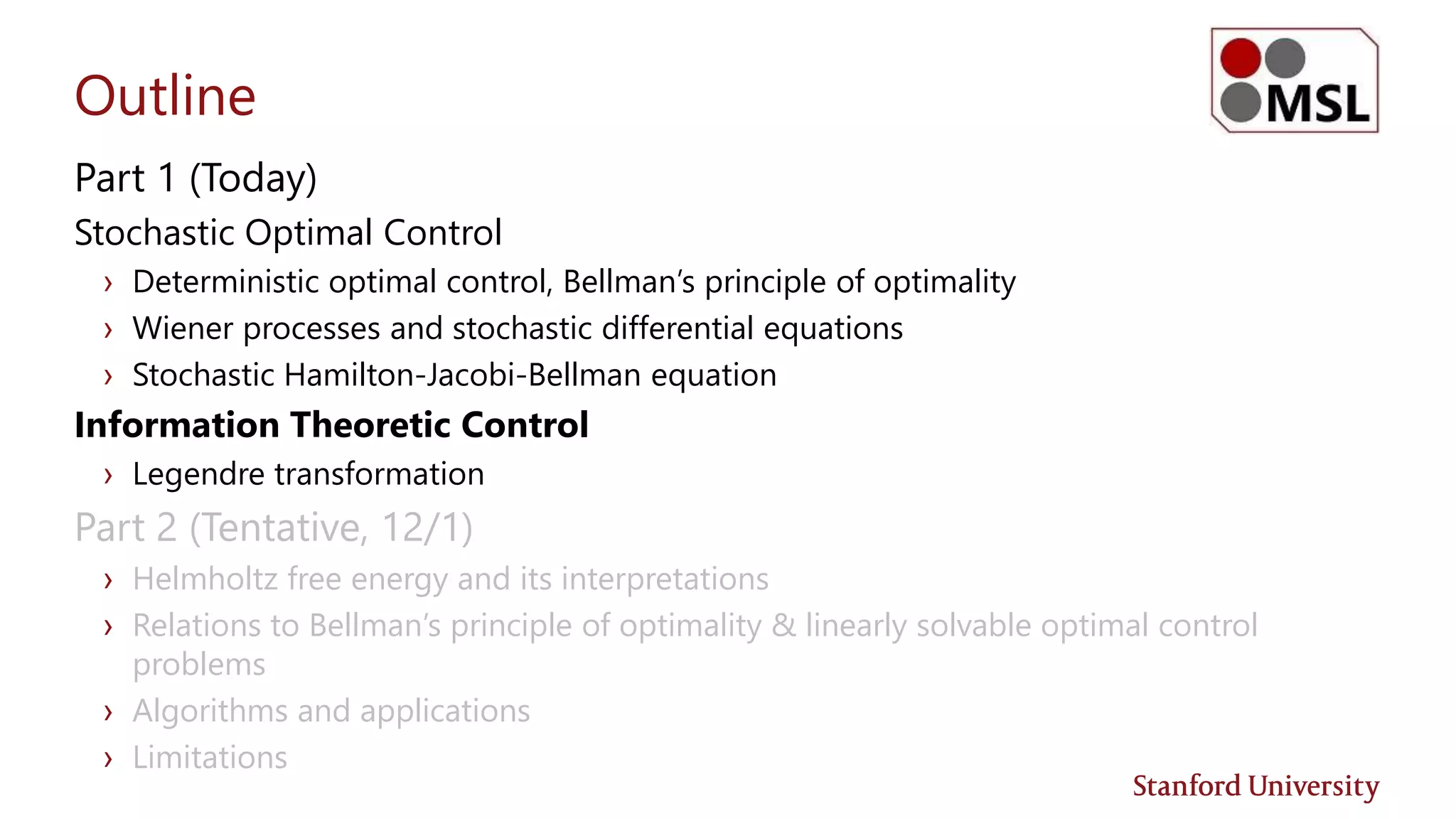

This document discusses stochastic optimal control and information theoretic dualities, highlighting two main approaches: stochastic dynamic programming and forward sampling of stochastic differential equations. It details the Hamilton-Jacobi-Bellman equation and its significance in stochastic control problems, alongside applications in fields such as finance and physics. Additionally, the document examines the Legendre transform as a method for understanding optimal control and its relation to Bellman's principle of optimality.

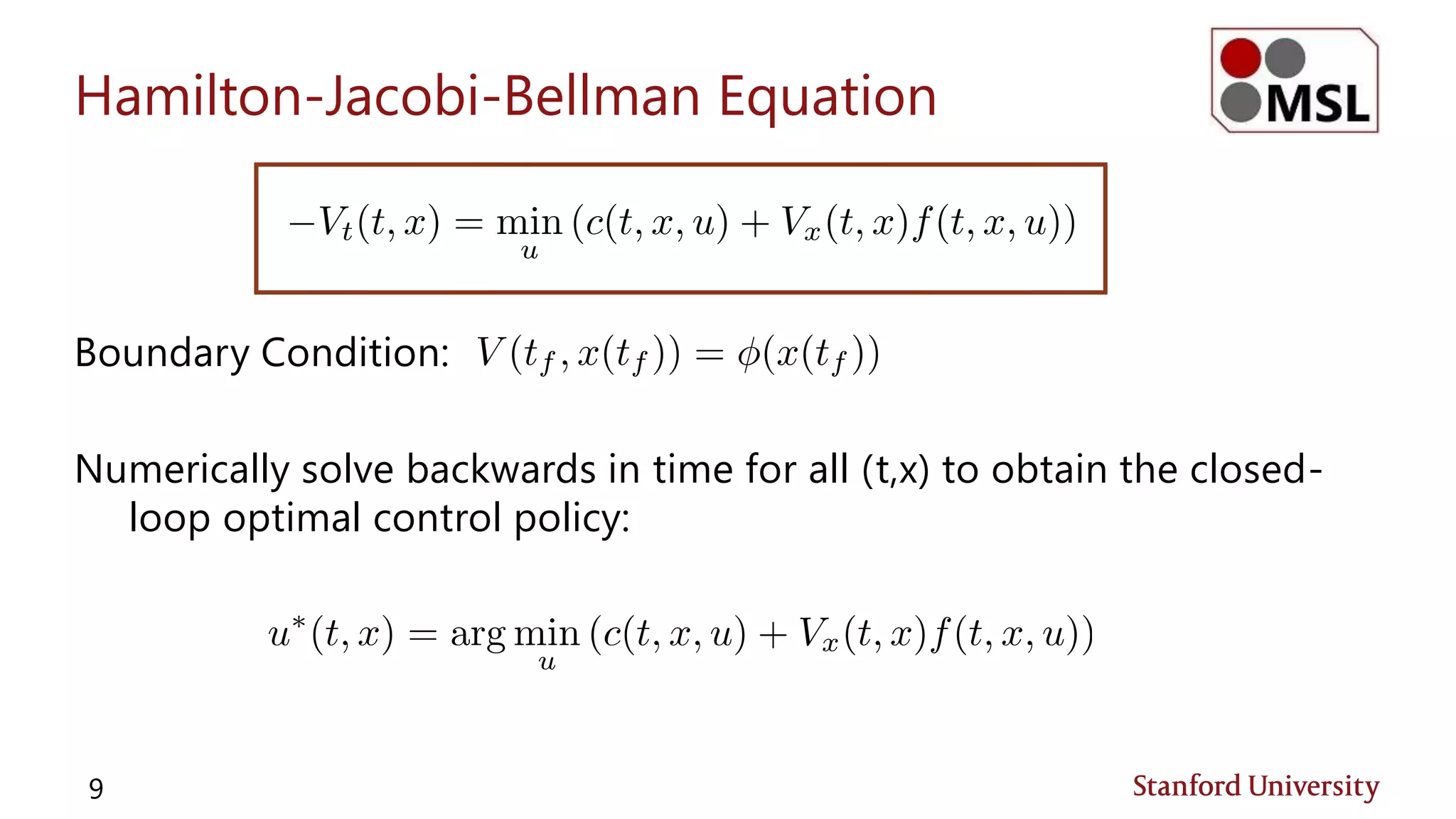

![The Big Picture

2 [Williams et al., 2017]

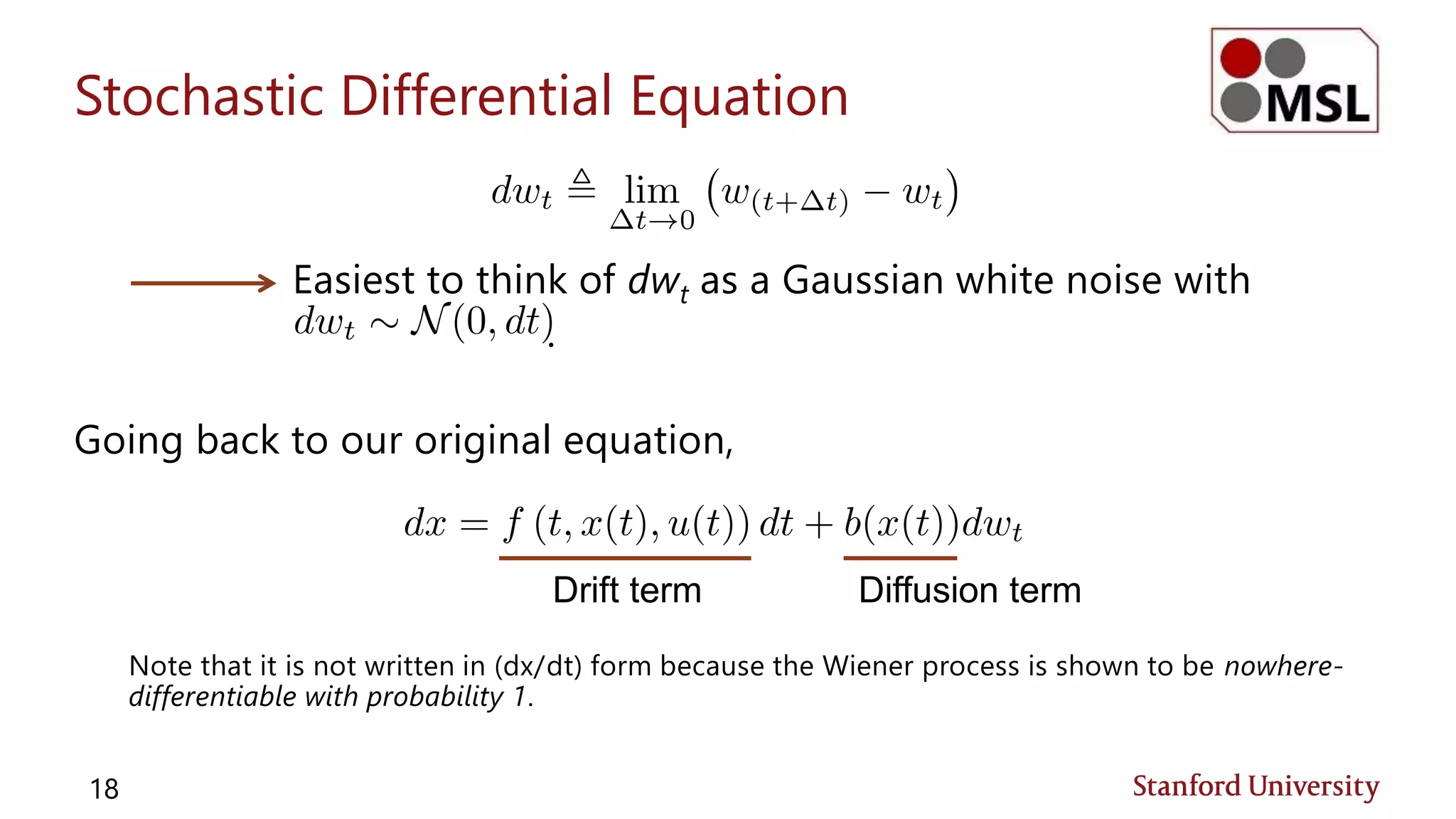

Stochastic Optimal Control Theory

• “Optimality” defined by Bellman’s

principle of optimality.

• Solution methods based on stochastic

dynamic programming.

Information Theoretic Control Theory

• “Optimality” defined in the sense of

Legendre transform.

• Solution methods based on forward

sampling of stochastic differential

equations.

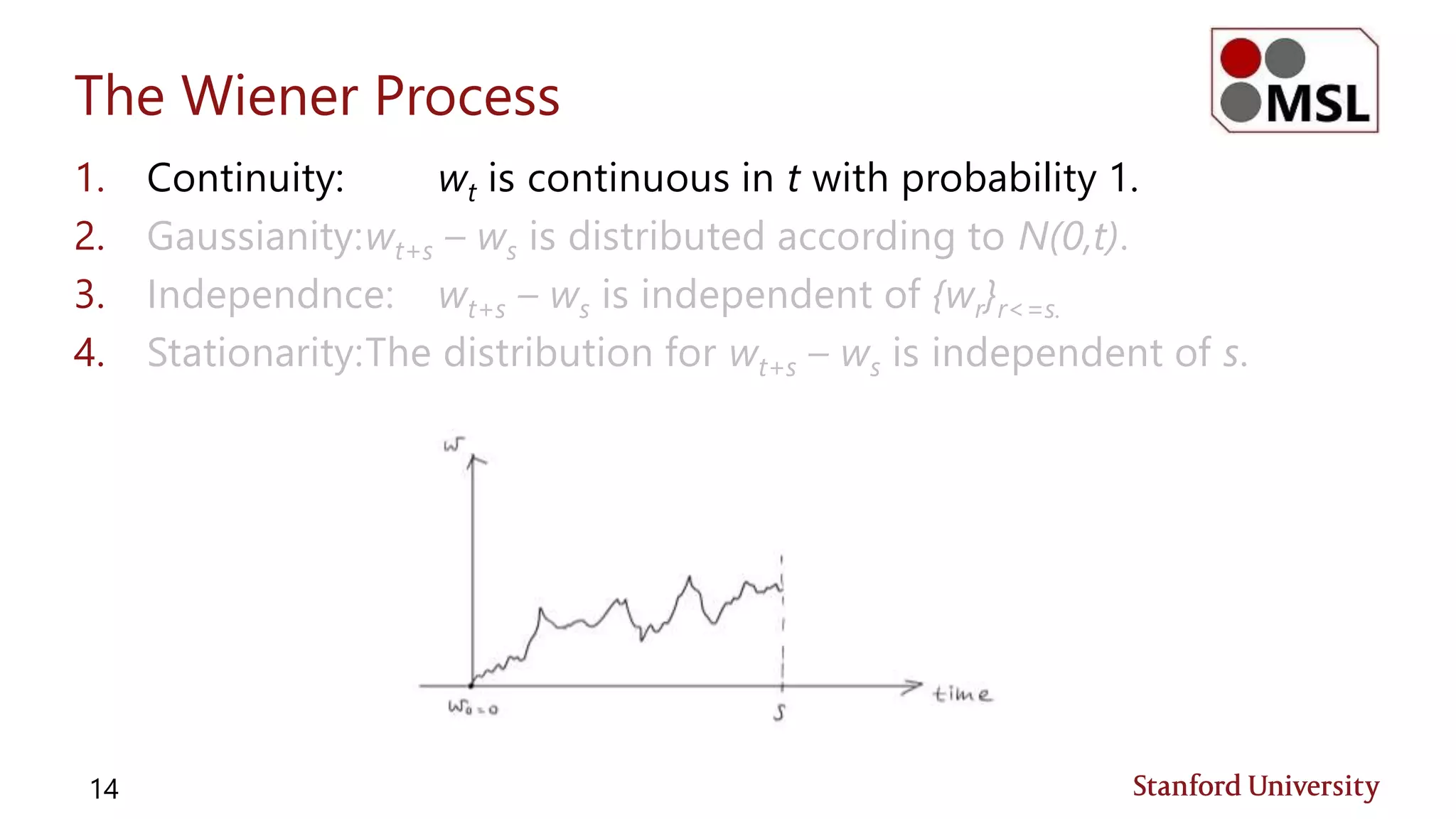

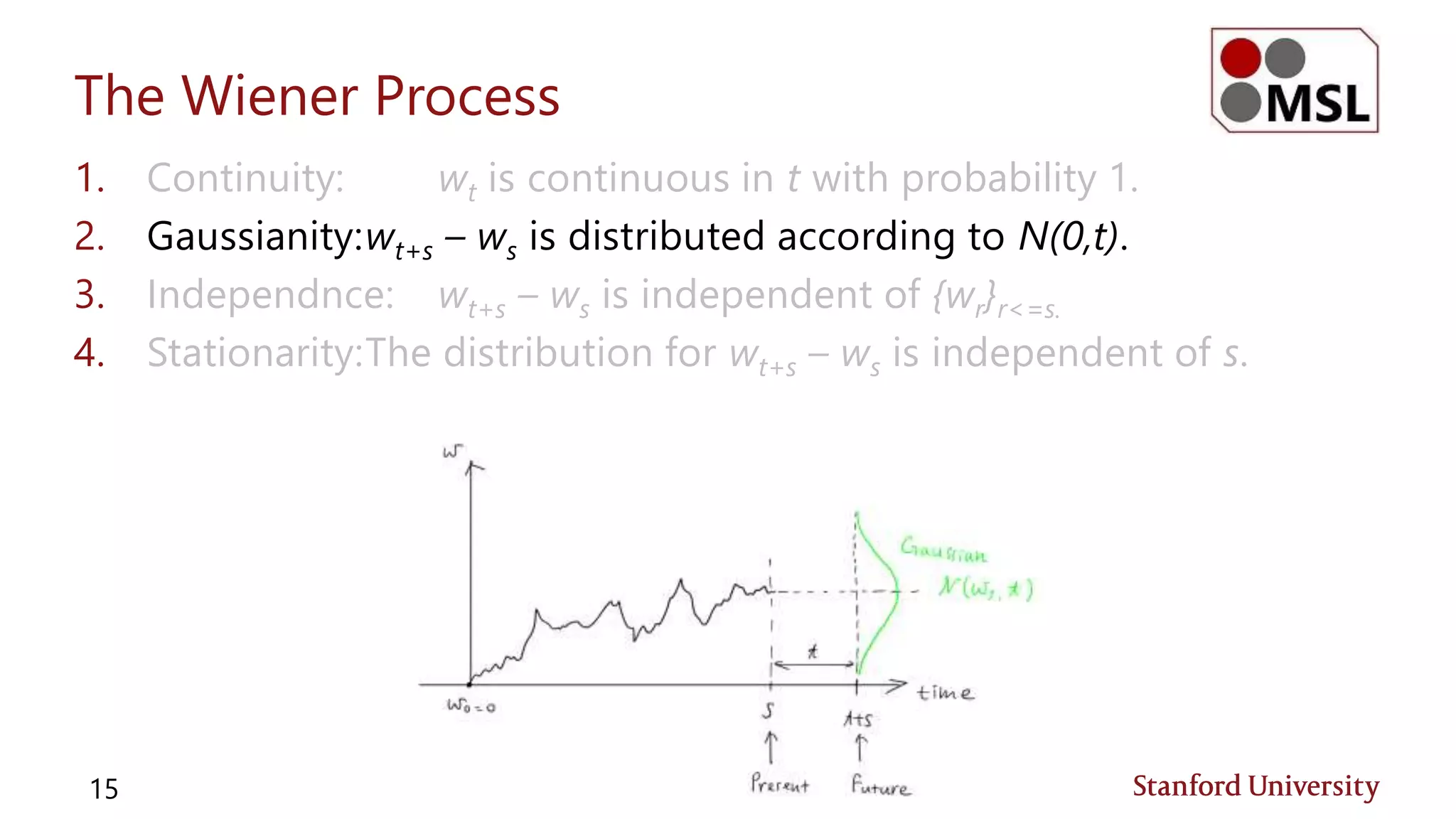

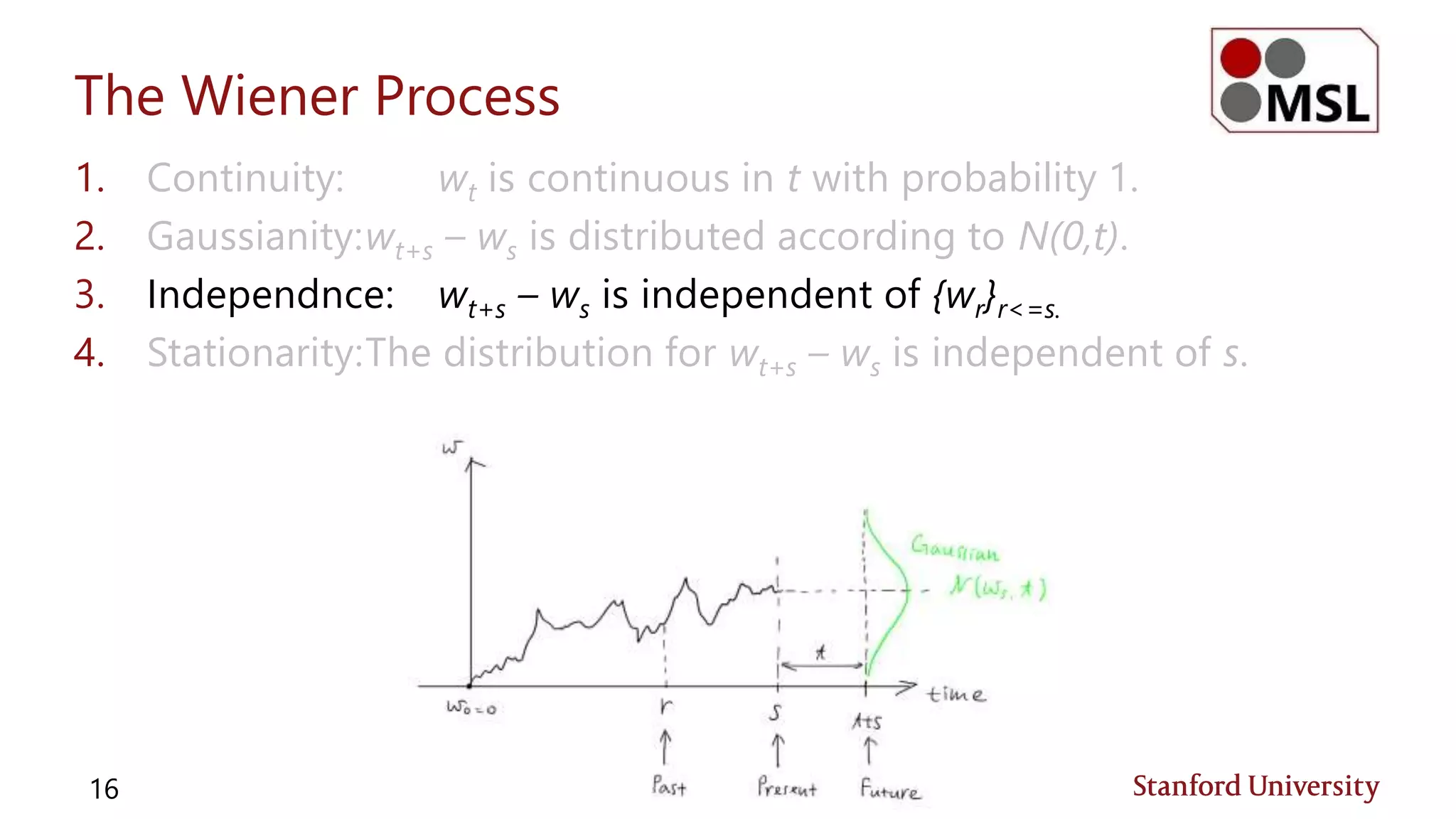

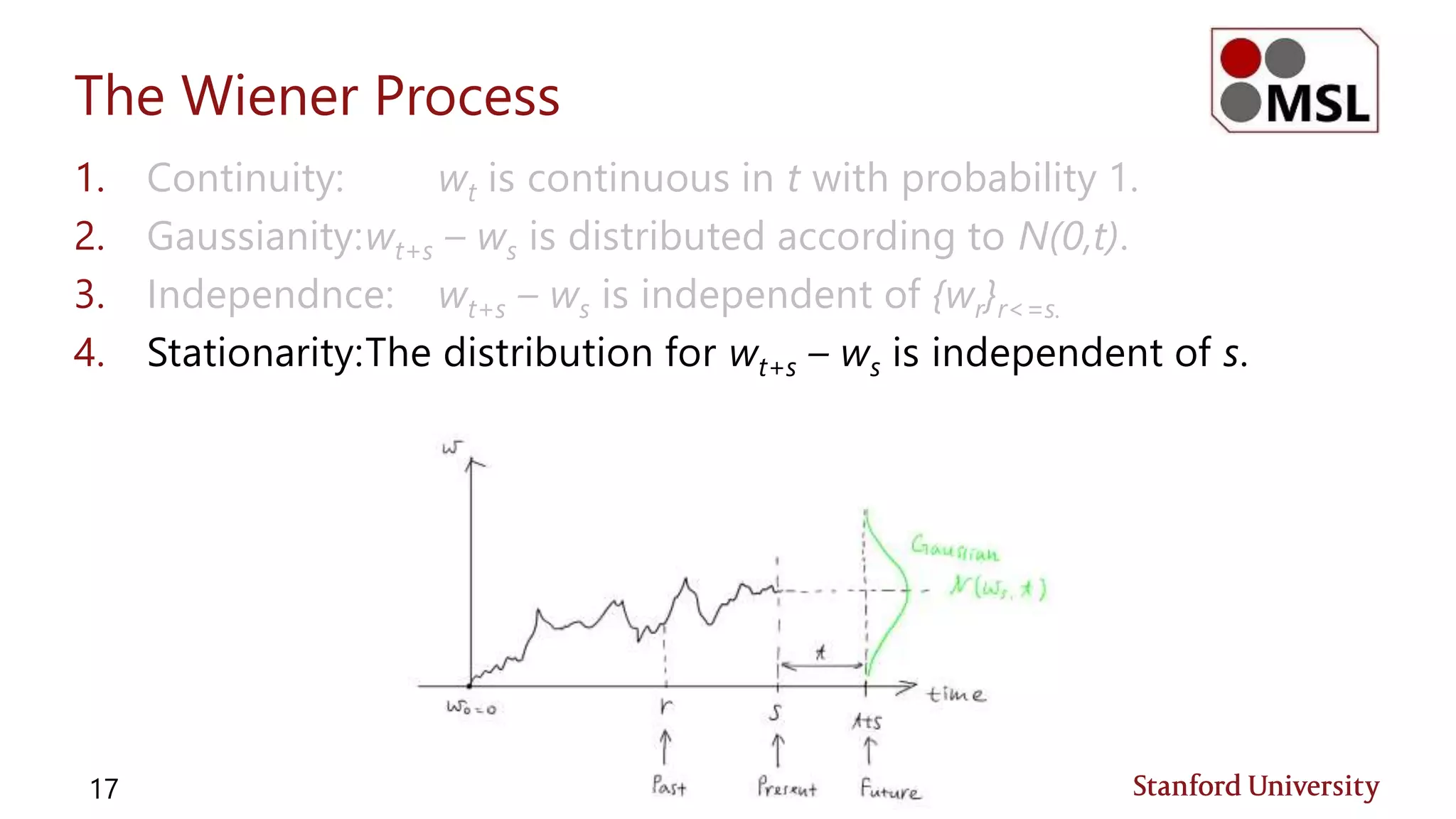

Two fundamentally different approaches to stochastic control problems.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/socitcdualities-171111051326/75/Stochastic-Optimal-Control-Information-Theoretic-Dualities-2-2048.jpg)

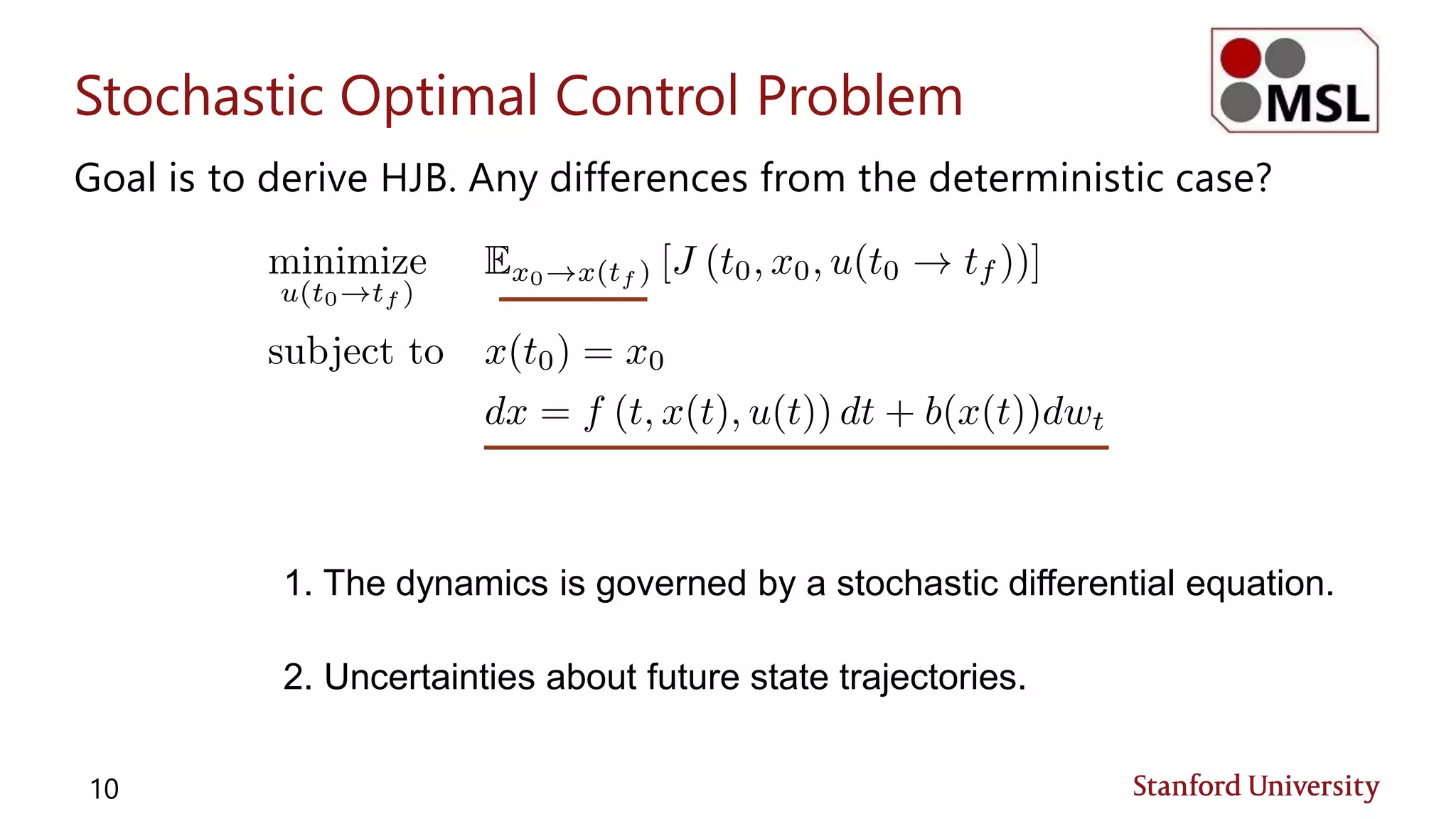

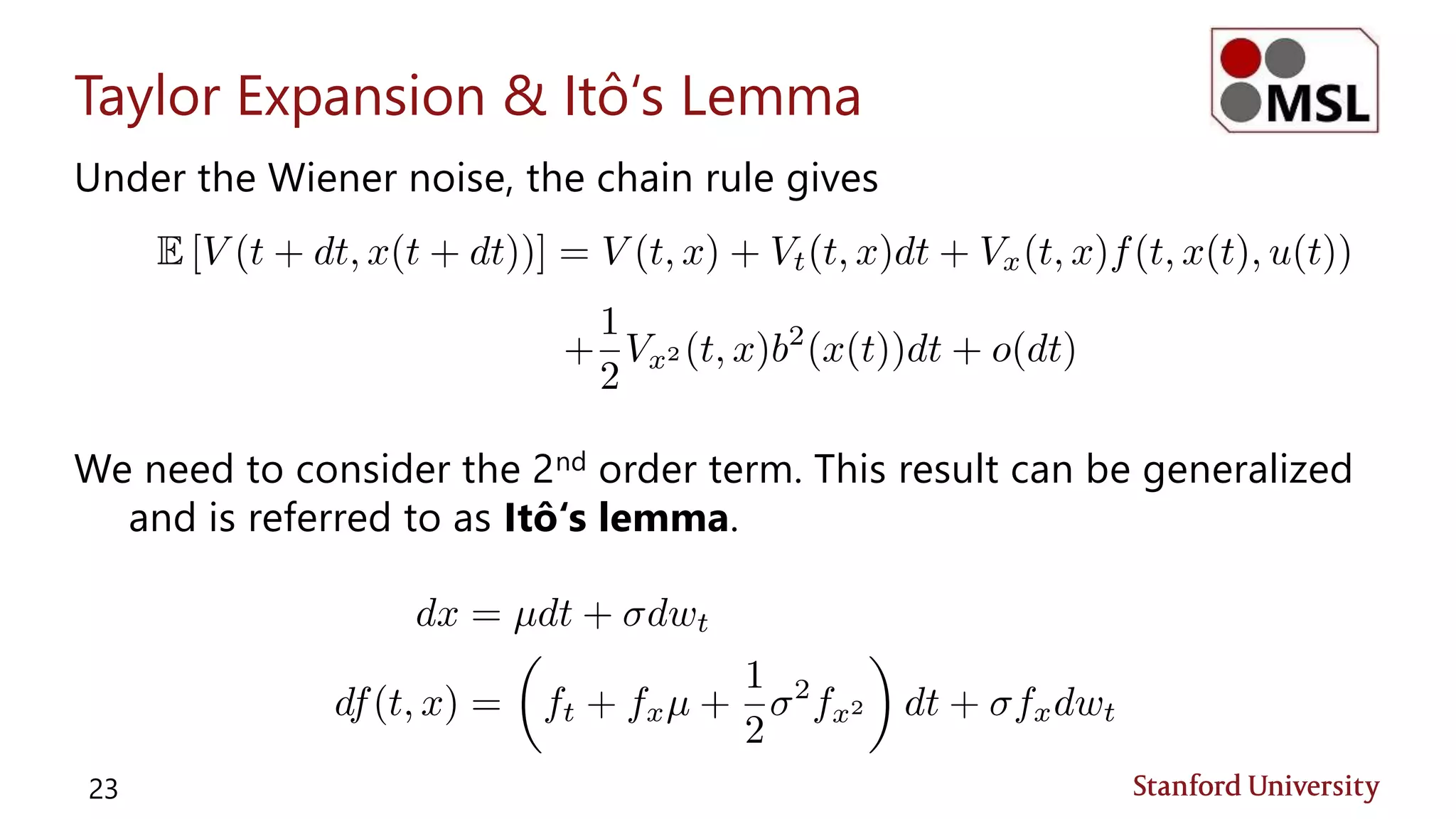

![The Big Picture

3 [Williams et al., 2017]

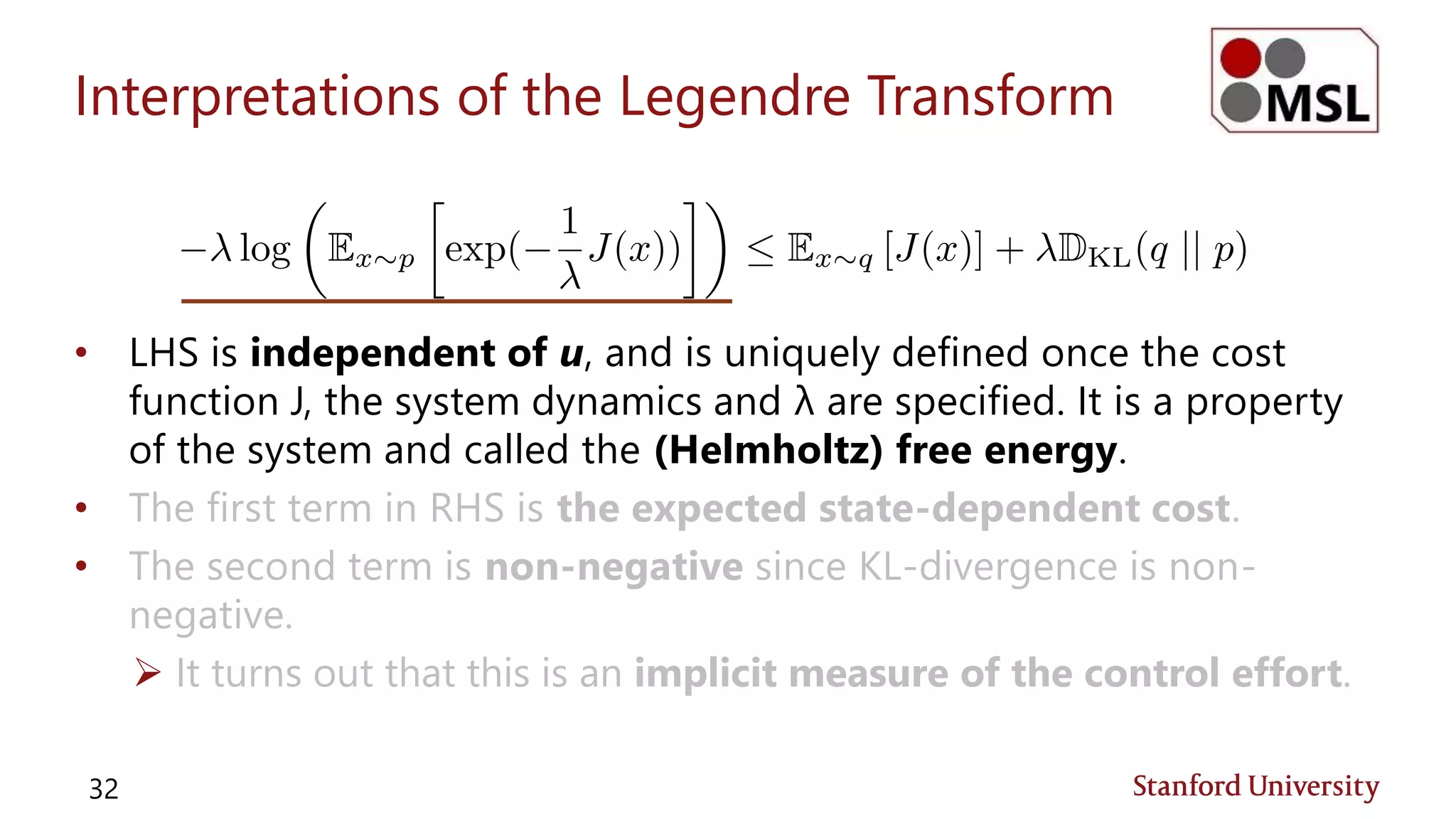

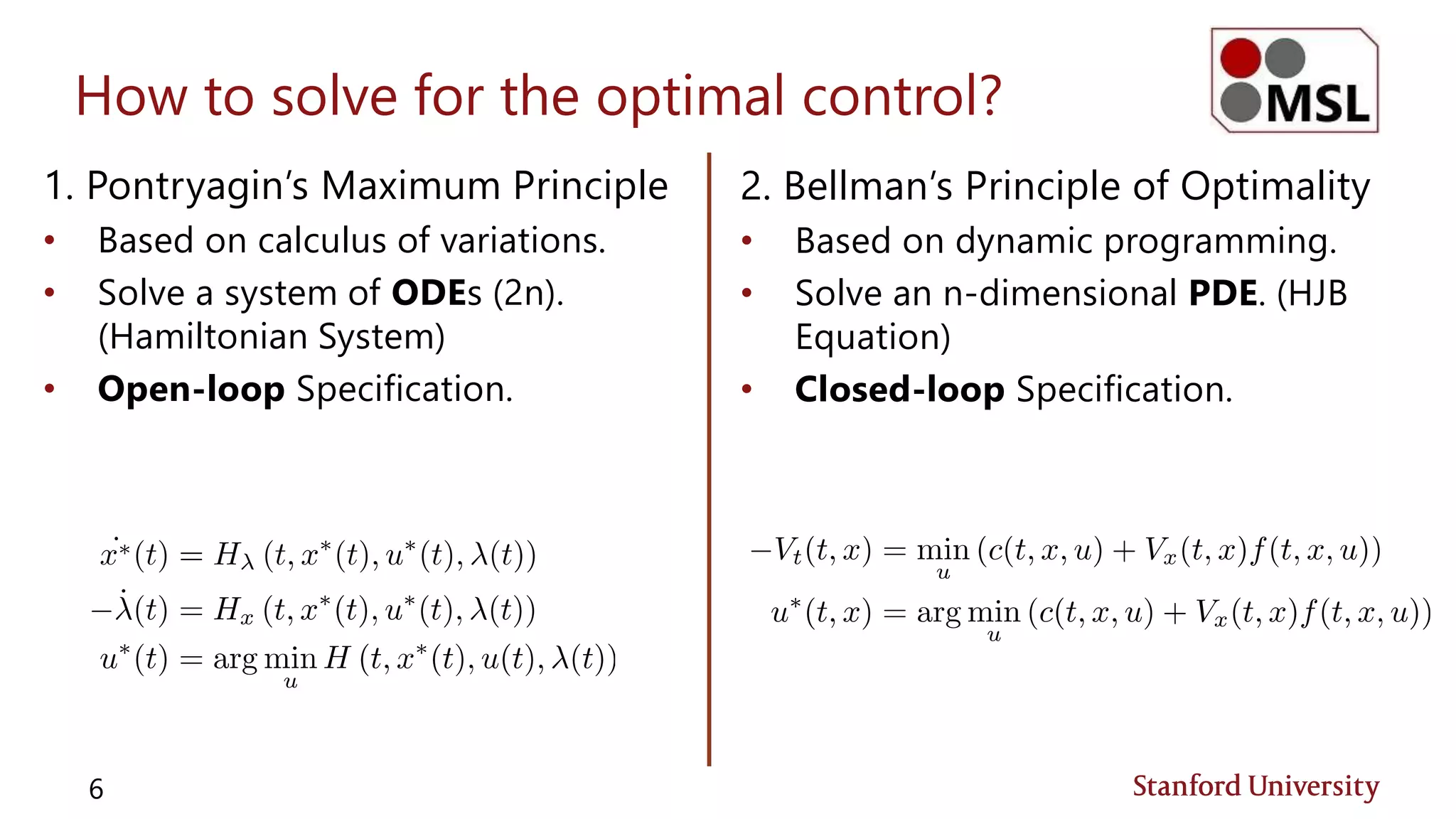

V(x0) Values of terminal states

x

0

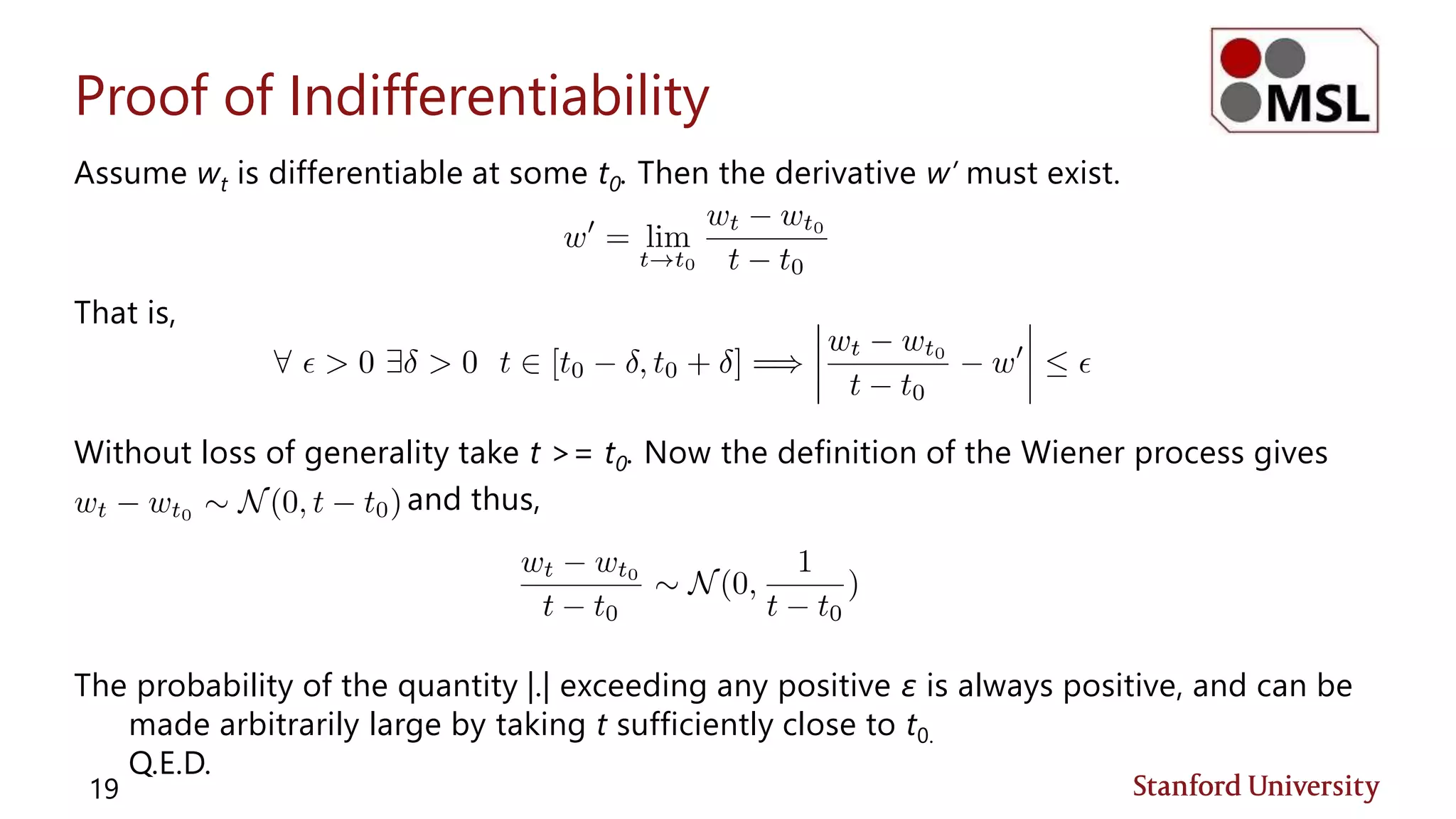

Stochastic Dynamic Programming

Forward Sampling of SDEs

Space of value

function

State space](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/socitcdualities-171111051326/75/Stochastic-Optimal-Control-Information-Theoretic-Dualities-3-2048.jpg)

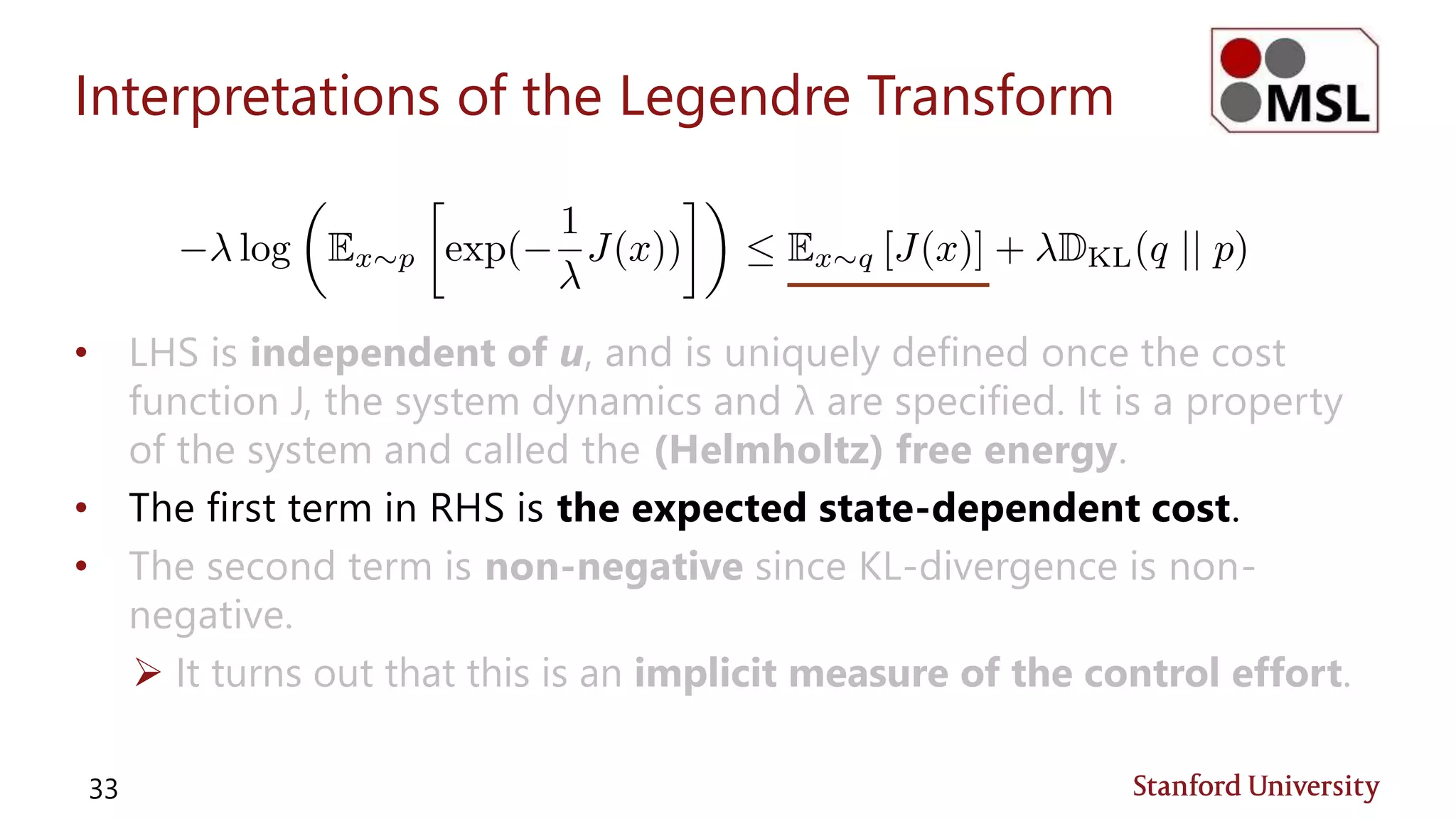

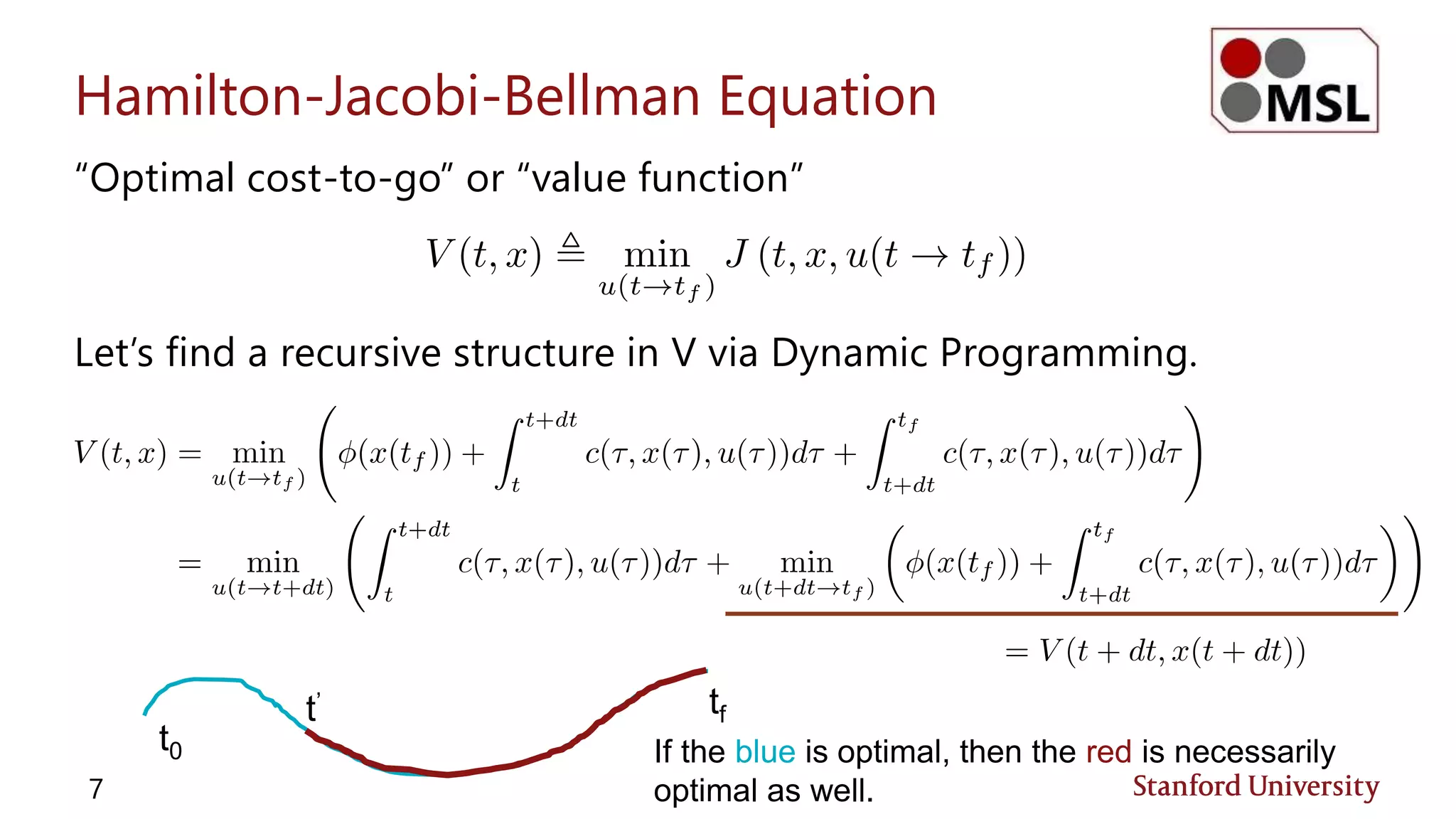

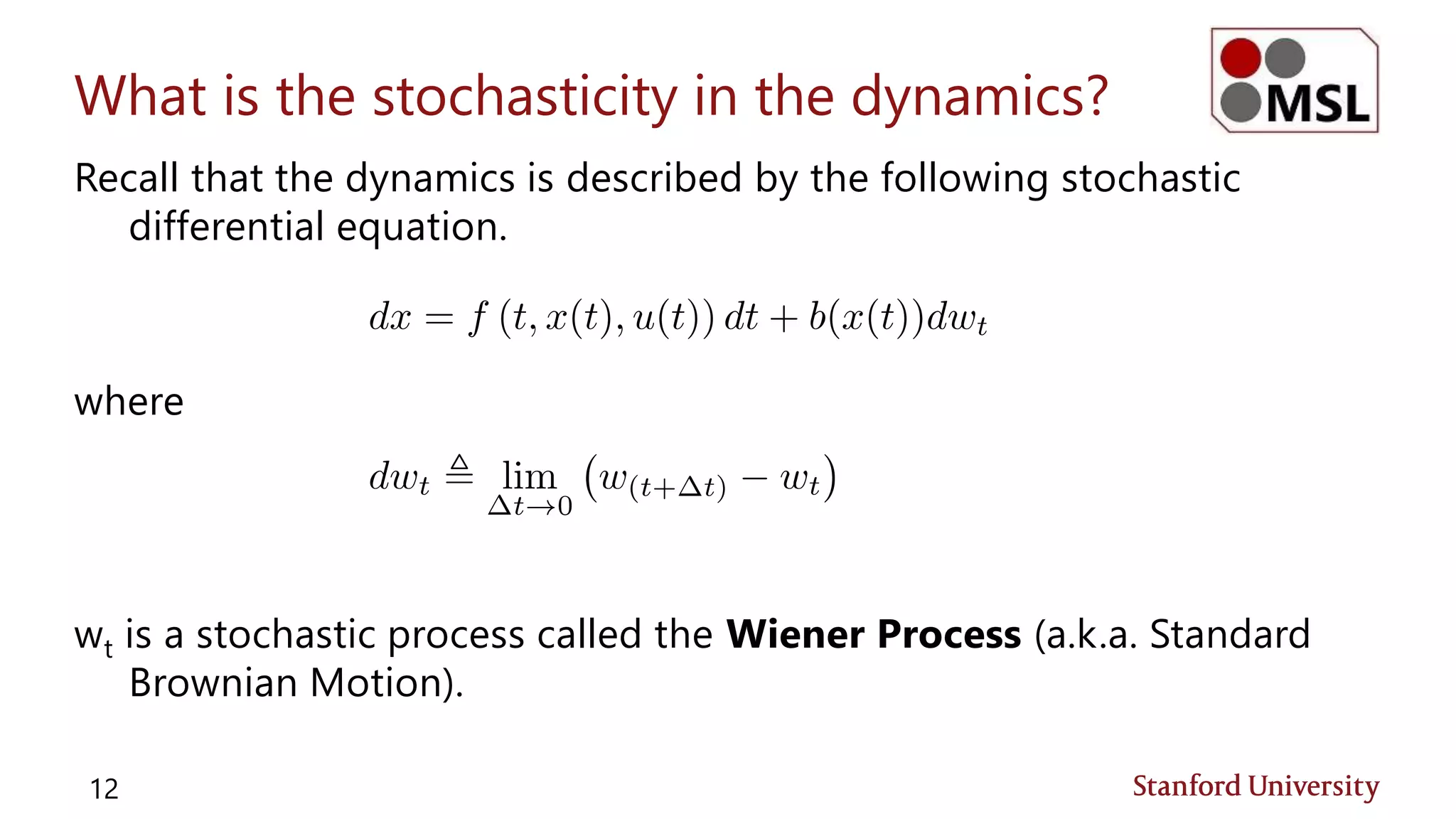

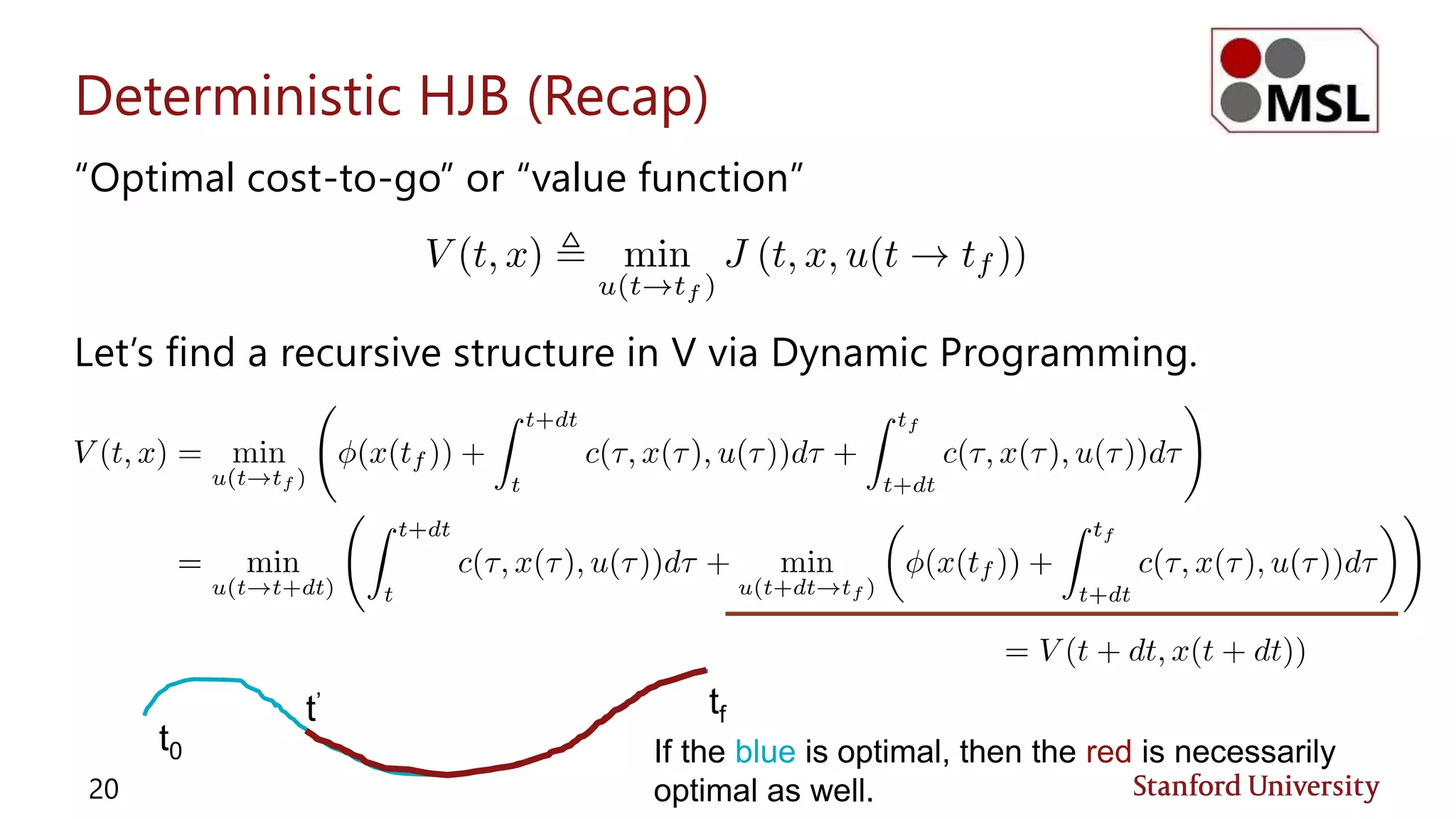

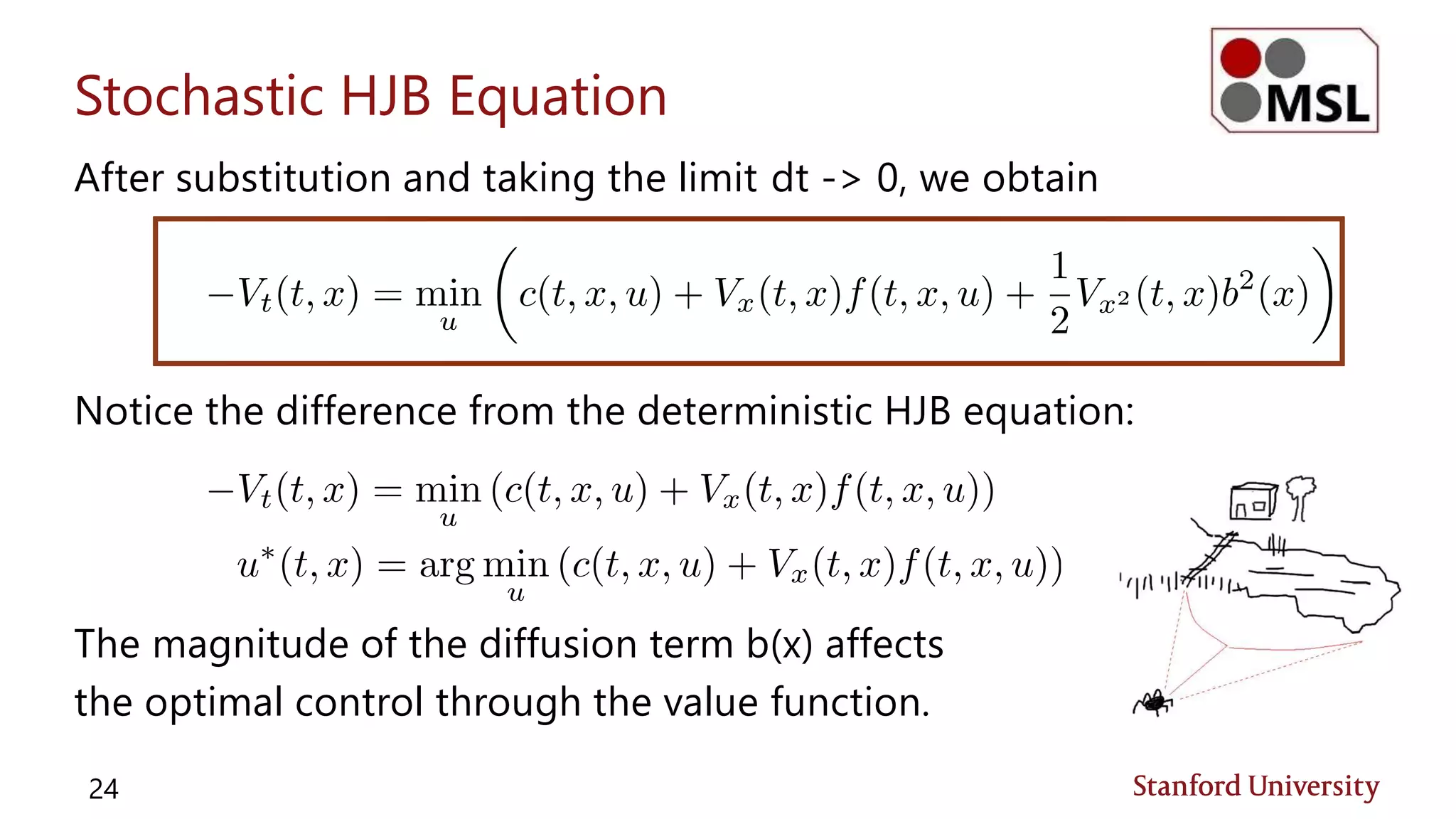

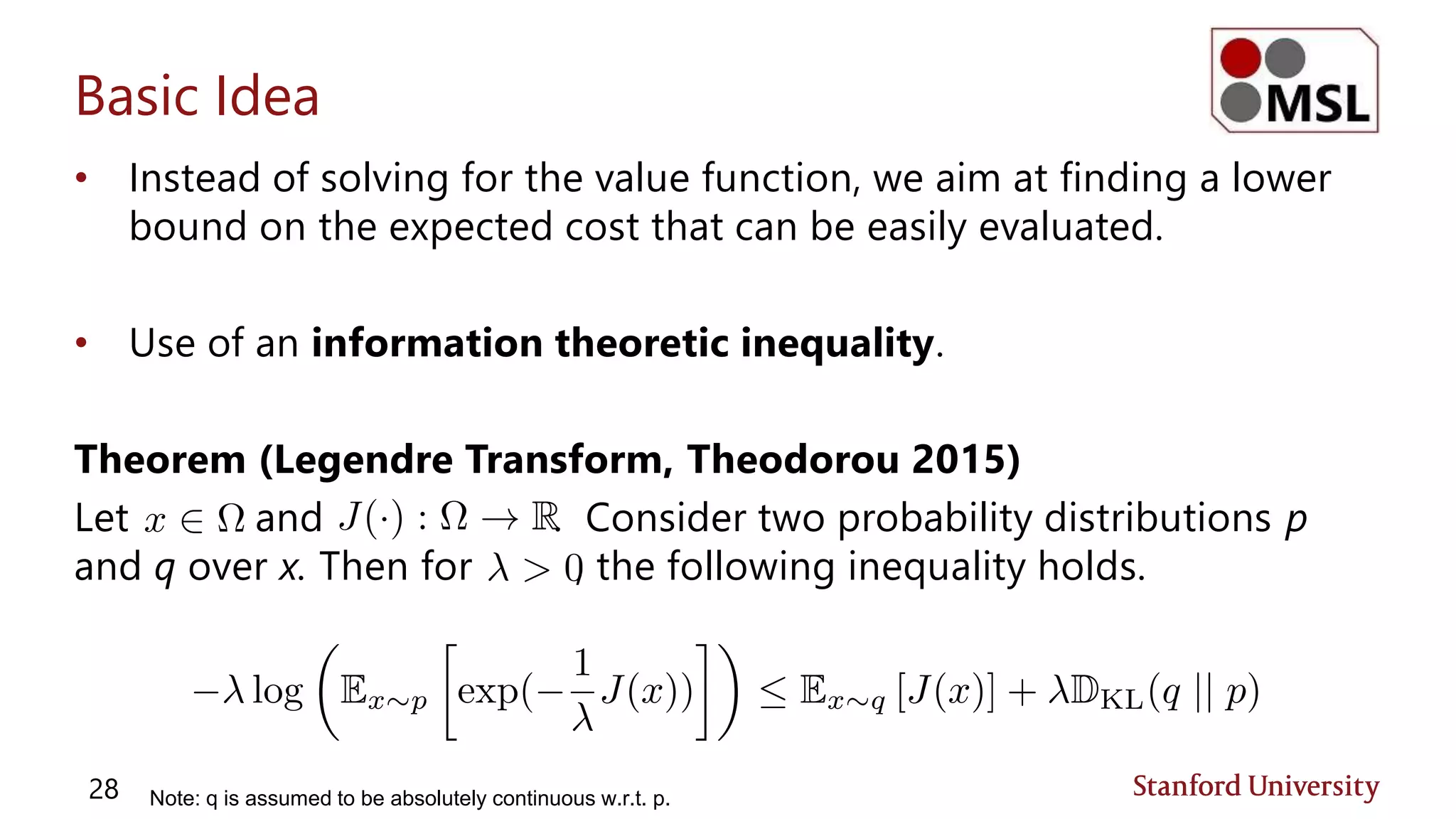

![Example: The Drunken Spider Problem

Presence of noise (alcohol) can change the optimal behavior

significantly.

11

• Without noise, the spider

will cross the bridge.

• When drunk, the cost of

crossing the bridge

increases and the spider

should go around the lake.

[Kappen, 2005]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/socitcdualities-171111051326/75/Stochastic-Optimal-Control-Information-Theoretic-Dualities-11-2048.jpg)

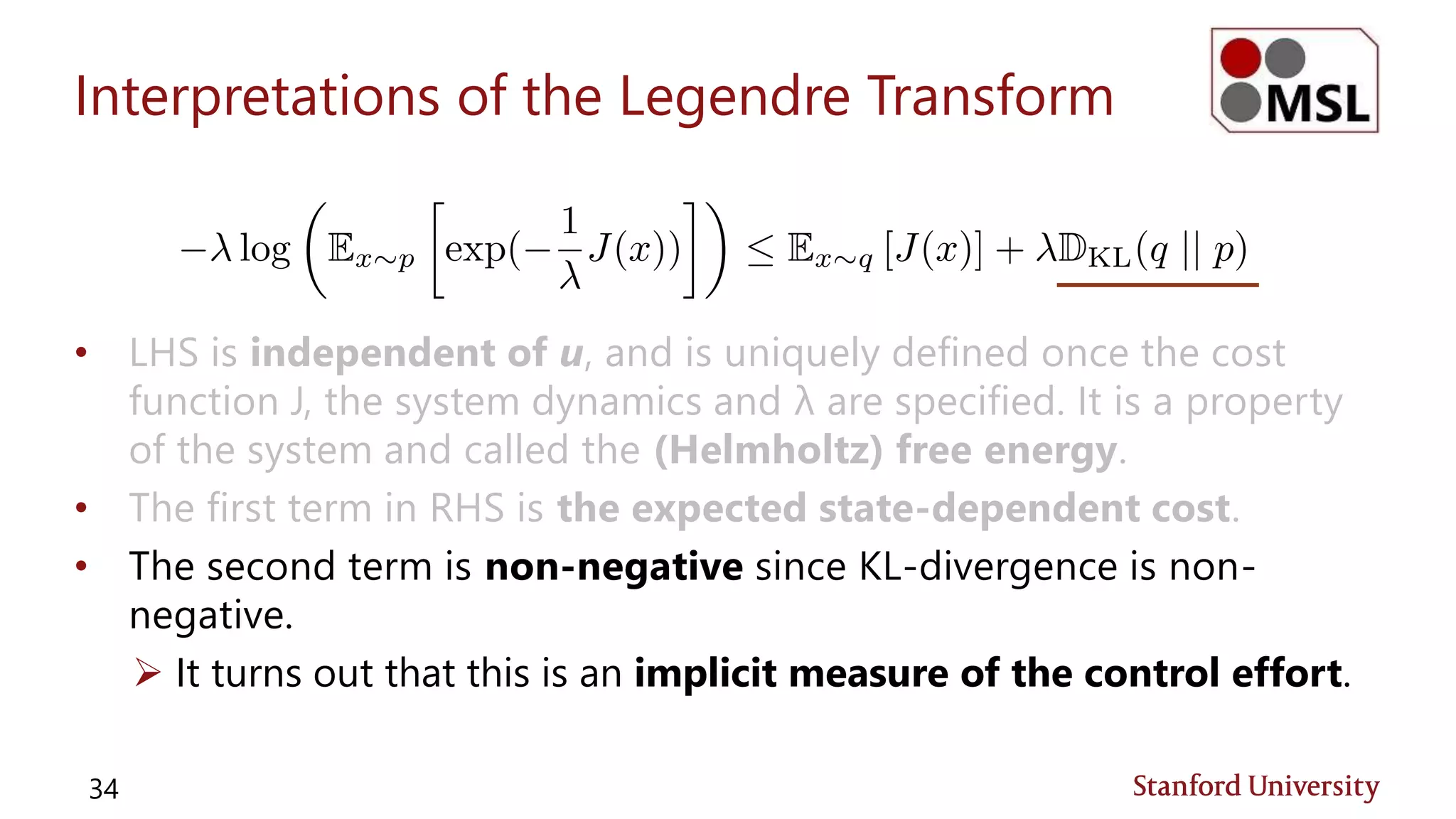

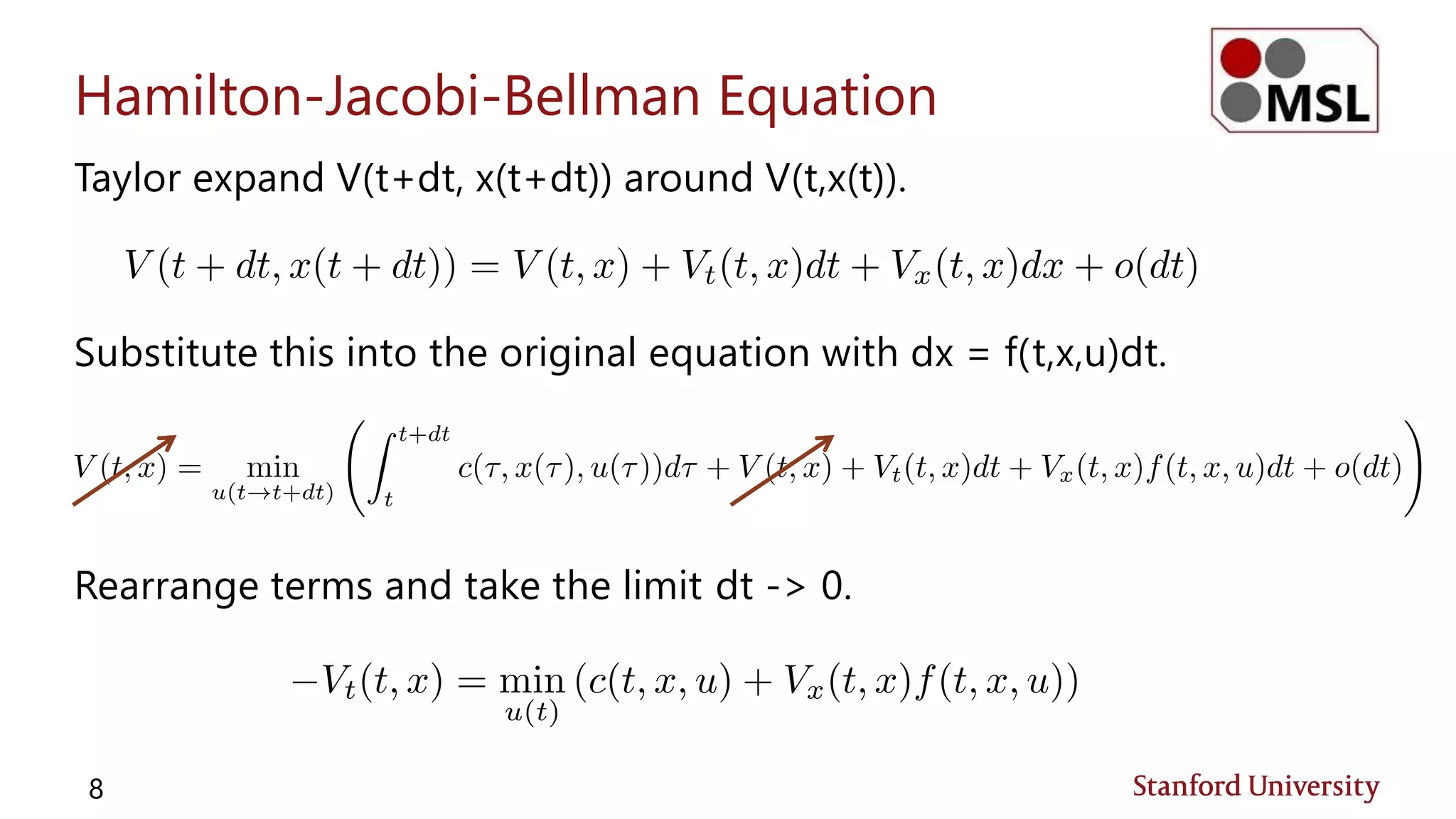

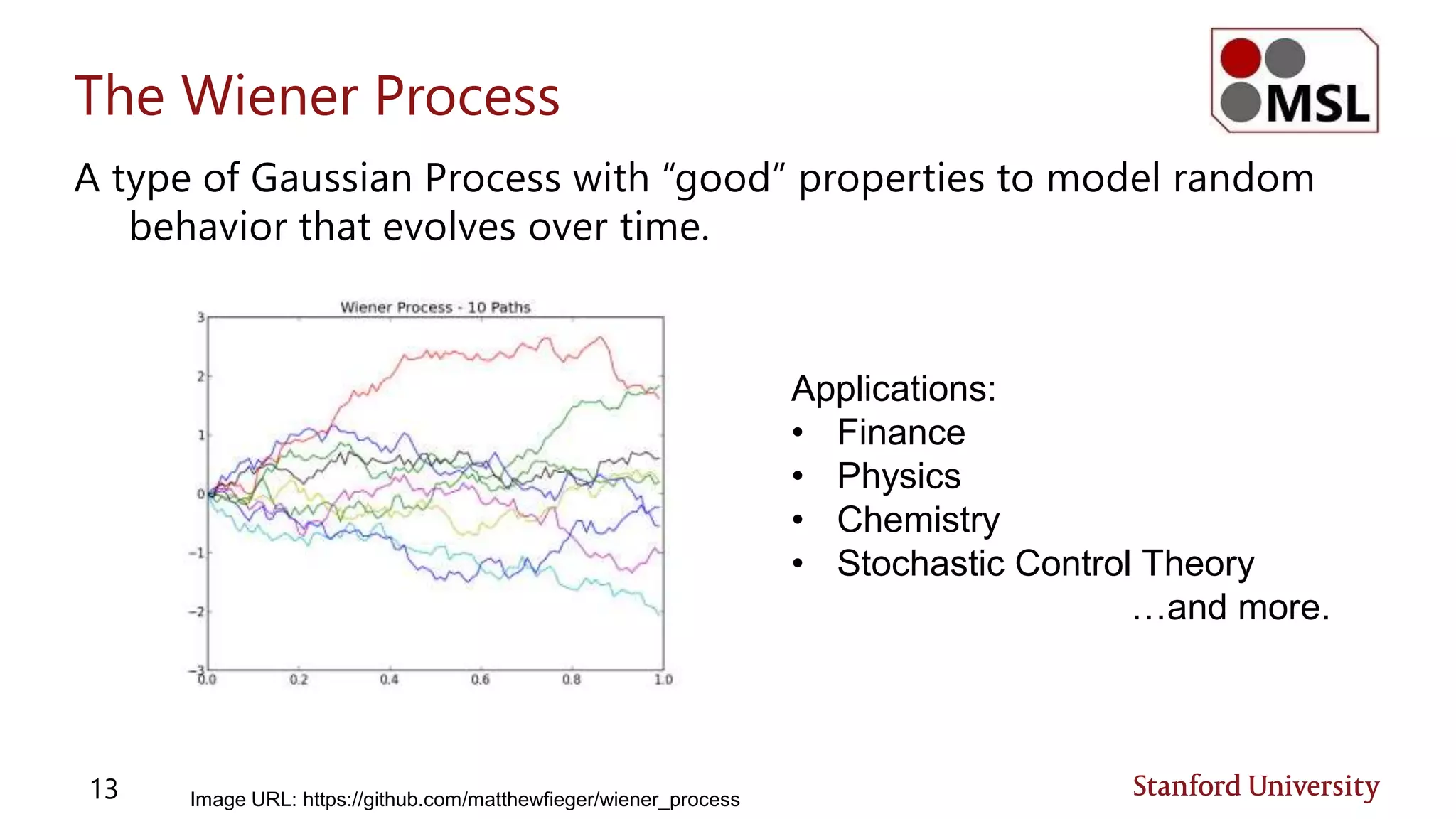

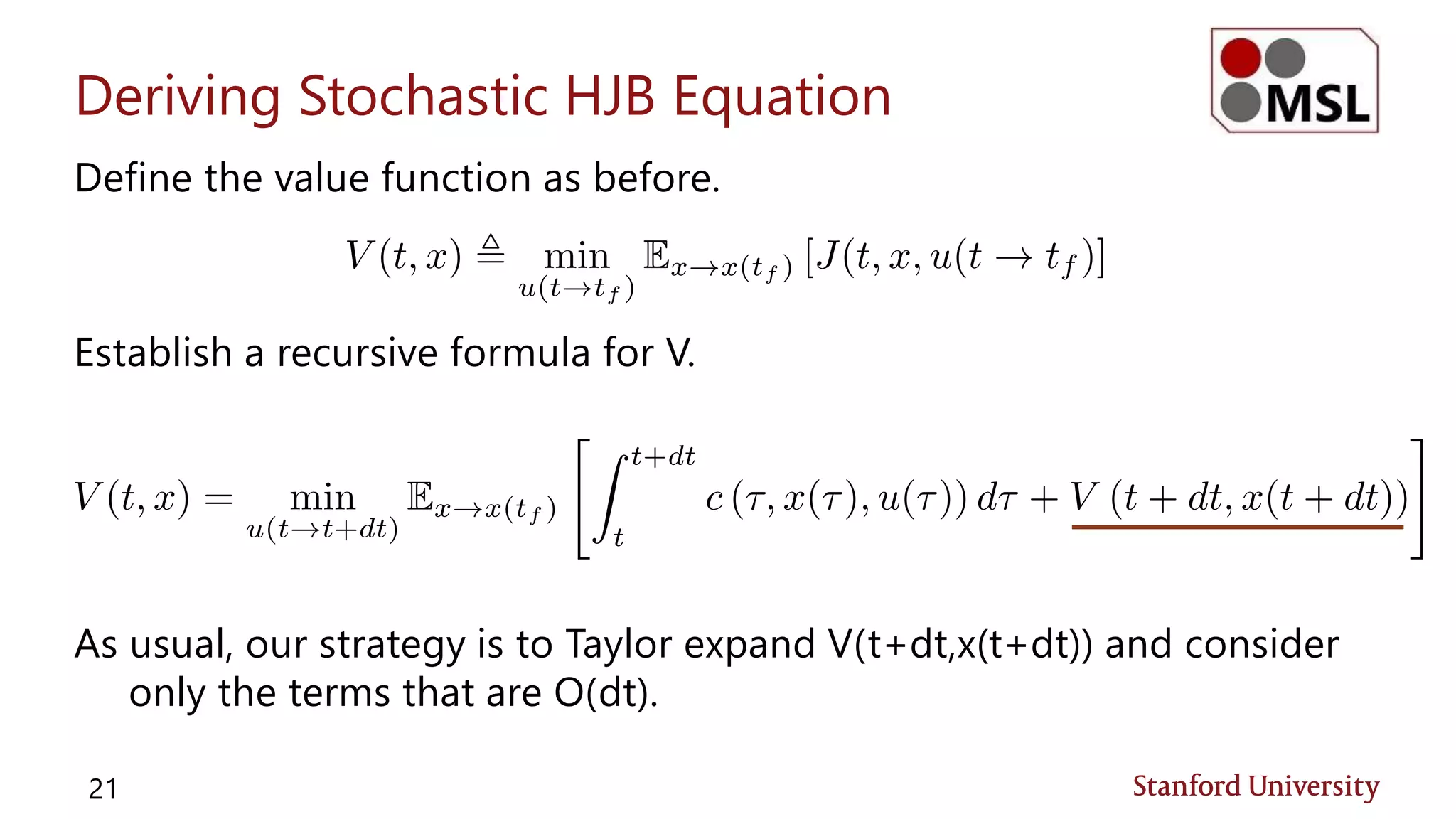

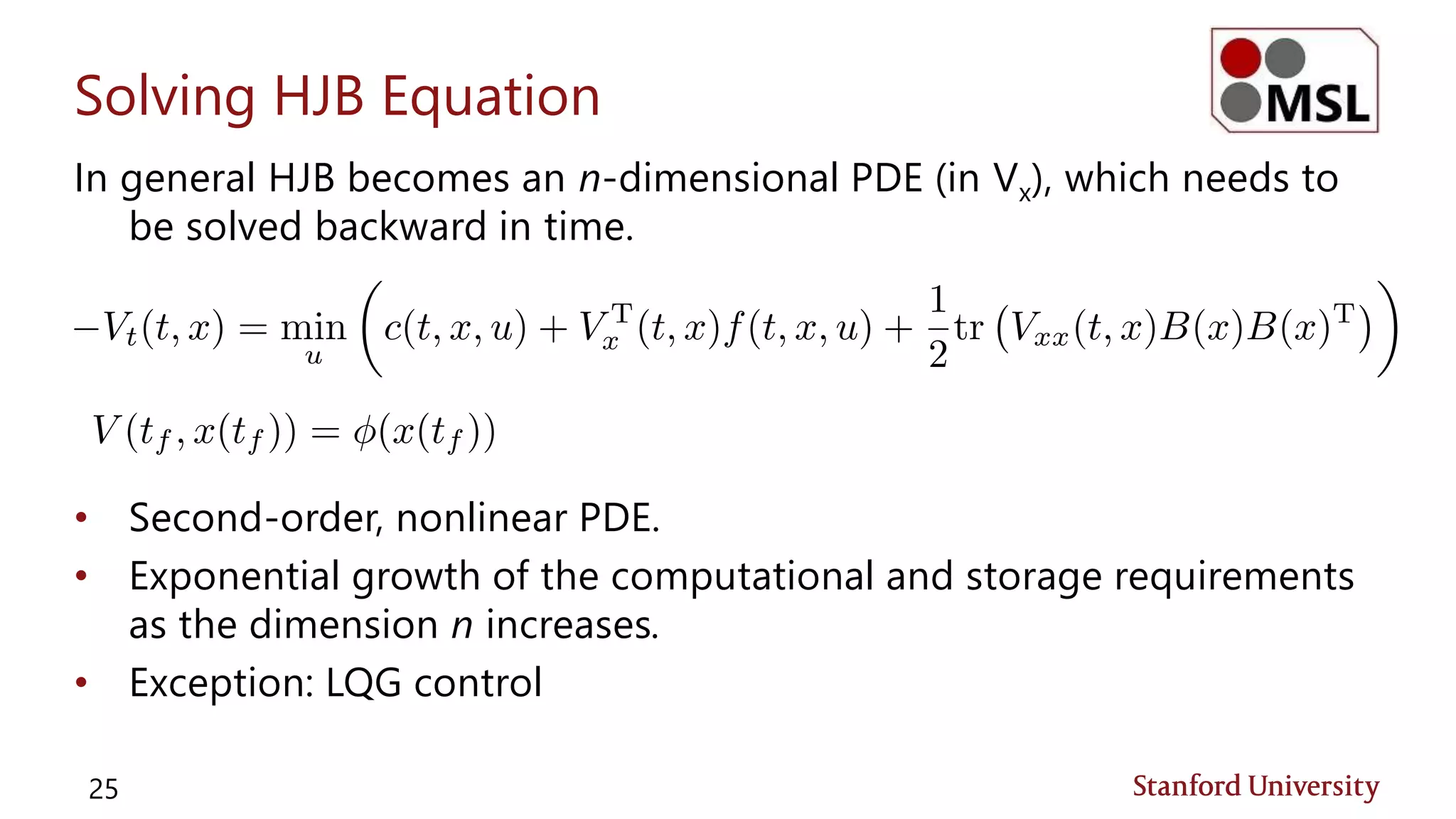

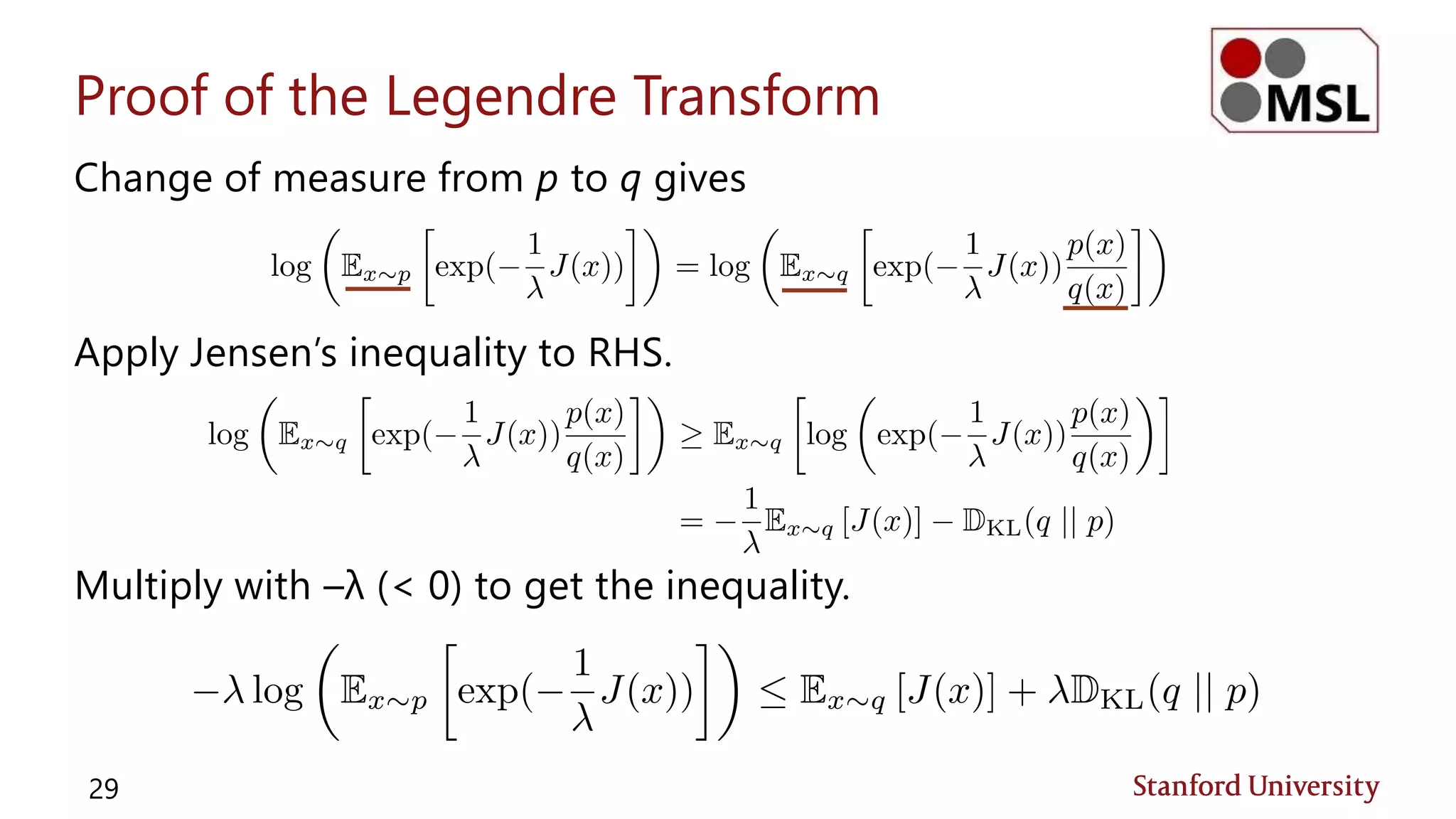

![Jensen’s Inequality (Review)

Let f be a convex function over a real-valued random variable X.

Then,

Furthermore, if f is strictly convex, the equality holds if and only if X =

E[X] with probability 1, in which case X is a deterministic constant.

In our case, log() is a strictly concave function, so the direction of the

inequality is flipped.

30](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/socitcdualities-171111051326/75/Stochastic-Optimal-Control-Information-Theoretic-Dualities-30-2048.jpg)