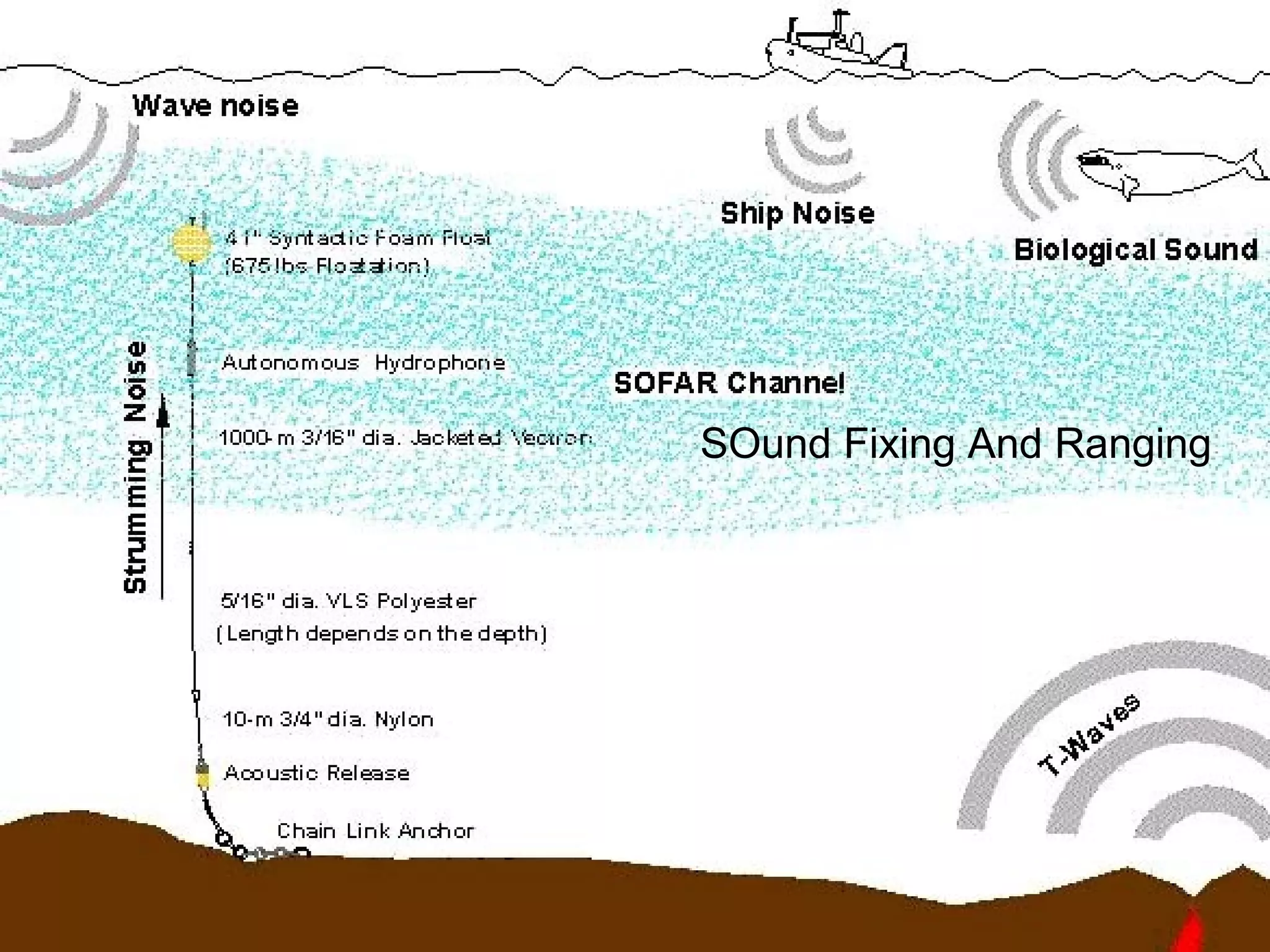

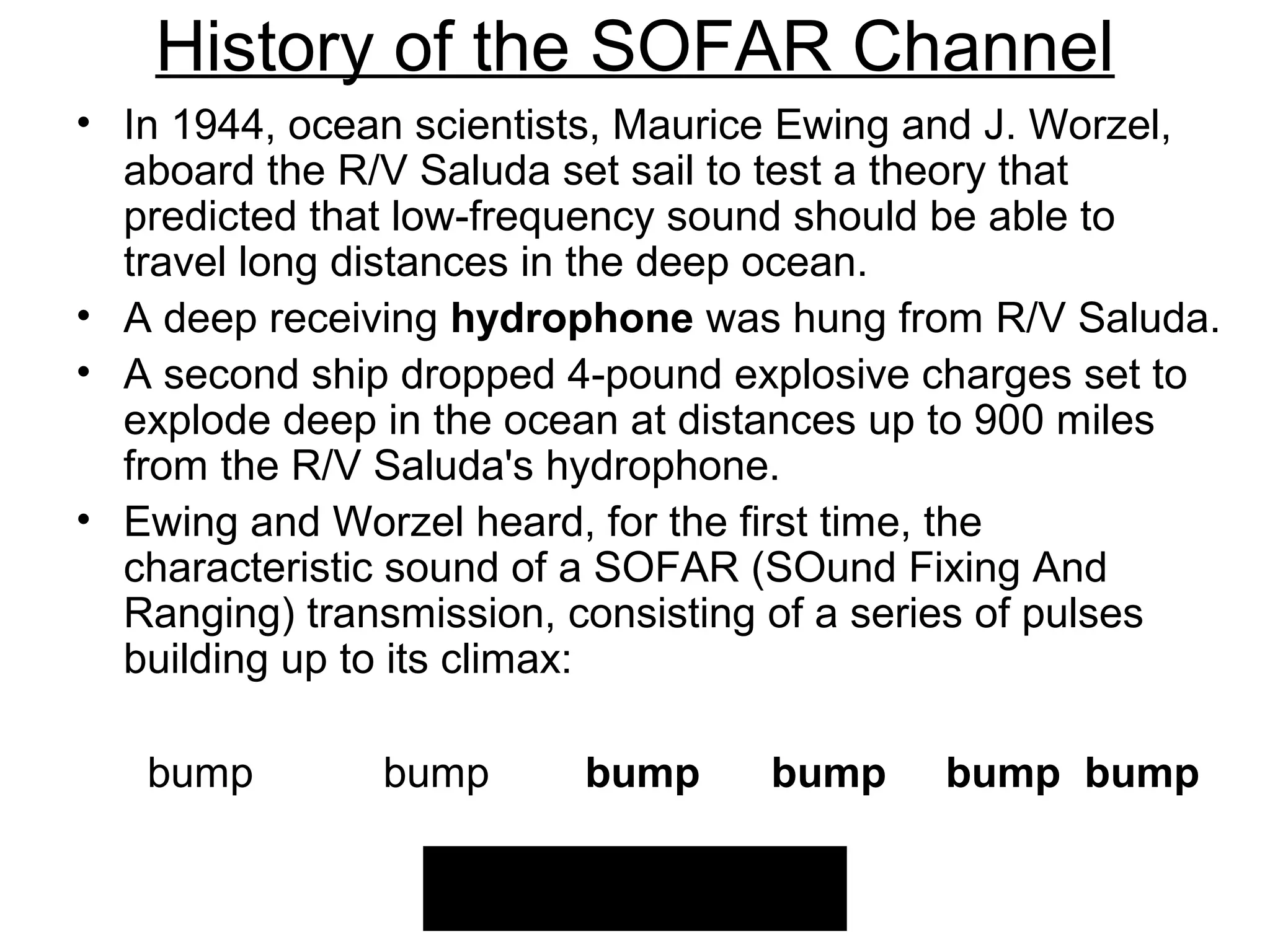

Scientists Ewing and Worzel conducted an experiment in 1944 where explosive charges were detonated at varying distances from a research vessel to test the theory that low-frequency sound could travel long distances underwater. Their experiment was successful and discovered the SOFAR channel, where sound waves are ducted horizontally in the ocean. This discovery led the US Navy to develop the SOSUS system during the Cold War to detect Soviet submarines over long ranges using hydrophone arrays. The SOFAR channel allows for underwater sound communication over hundreds of miles and has applications in navigation, climate monitoring, and wildlife observation.