This document discusses various techniques for enhancing the performance of .NET applications, including:

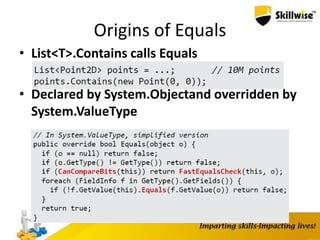

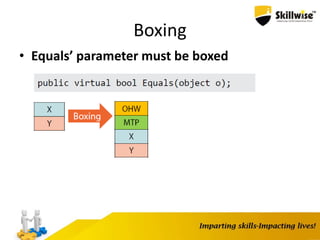

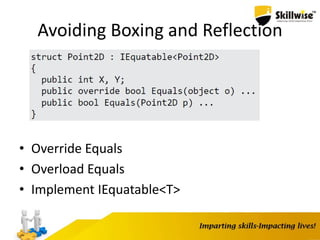

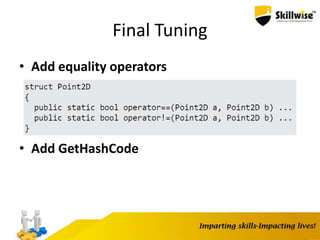

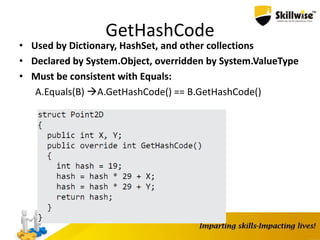

1) Implementing value types correctly by overriding Equals, GetHashCode, and IEquatable<T> to avoid boxing;

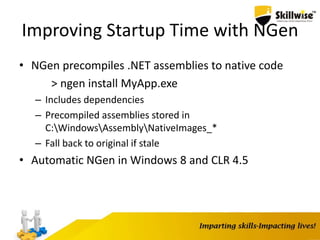

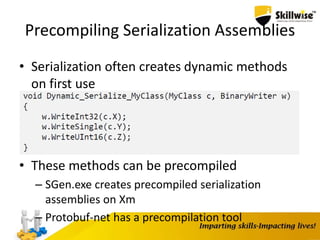

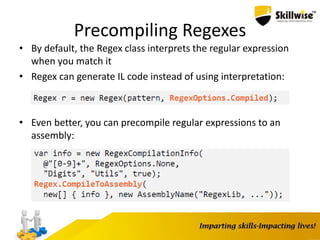

2) Applying precompilation techniques like NGen to improve startup time;

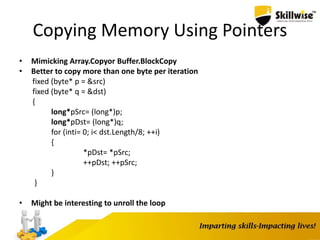

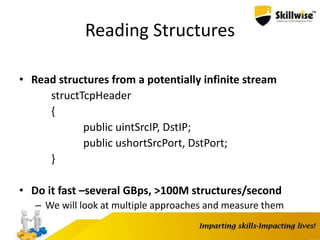

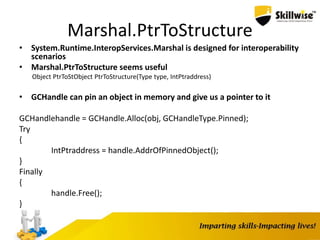

3) Using unsafe code and pointers for high-performance scenarios like reading structures from streams at over 100 million structures per second;

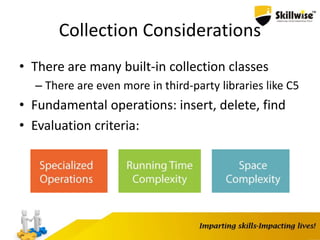

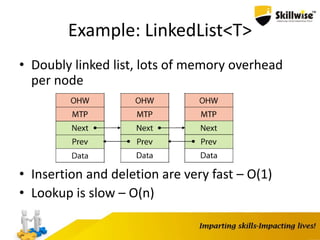

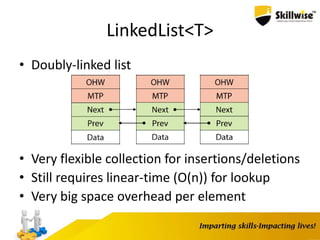

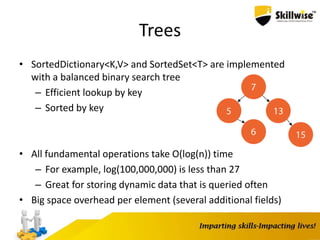

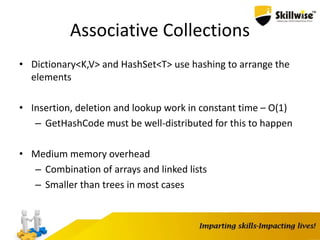

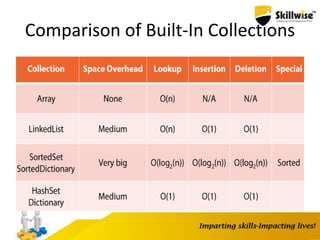

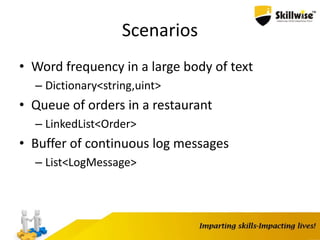

4) Choosing appropriate collection types like dictionaries for fast lookups or linked lists for fast insertions/deletions.

![Pointers and Pinning

• We want to go from byte[]to byte*

• When getting a pointer to a heap object, what if the GC moves it?

• Pinning is required

byte[] source = ...;

fixed(byte* p = &source)

{

...

}

• Directly manipulate memory

*p = (byte)12;

int x = *(int*)p;

• Requires unsafeblock and “Allow unsafe code”](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/enhancingdotnetapp-150923051627-lva1-app6892/85/Skillwise-Enhancing-dotnet-app-26-320.jpg)

![The Pointer-Free Approach

TcpHeaderRead(byte[] data, intoffset)

{

MemoryStreamms= new MemoryStream(data);

BinaryReaderbr= new BinaryReader(ms);

TcpHeaderresult = new TcpHeader();

result.SrcIP= br.ReadUInt32();

result.DstIP= br.ReadUInt32();

result.SrcPort= br.ReadUInt16();

result.DstPort= br.ReadUInt16();

return result;

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/enhancingdotnetapp-150923051627-lva1-app6892/85/Skillwise-Enhancing-dotnet-app-29-320.jpg)

![Using Pointers

• Pointers can help by casting

fixed (byte* p = &data[offset])

{

TcpHeader* pHeader= (TcpHeader*)p;

return *pHeader;

}

• Very simple, doesn’t require helper routines](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/enhancingdotnetapp-150923051627-lva1-app6892/85/Skillwise-Enhancing-dotnet-app-31-320.jpg)

![A Generic Approach

• Unfortunately, T*doesn’t work –T must be blittable

unsafe T Read(byte[] data, int offset)

{

fixed (byte* p = &data[offset])

{

return *(T*)p;

}

}

• We can generate a method for each T and call it when necessary

– Reflection.Emit

– CSharpCodeProvider

– Roslyn](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/enhancingdotnetapp-150923051627-lva1-app6892/85/Skillwise-Enhancing-dotnet-app-32-320.jpg)

![List<T>

• Dynamic (resizable) array

– Doubles its size with each expansion

– For 100,000,000 insertions: [log 100,000,000] = 27

expansions

• Insertions not at the end are very expensive

– Good for append-only data

• No specialized lookup facility

• Still no per-element overhead](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/enhancingdotnetapp-150923051627-lva1-app6892/85/Skillwise-Enhancing-dotnet-app-37-320.jpg)

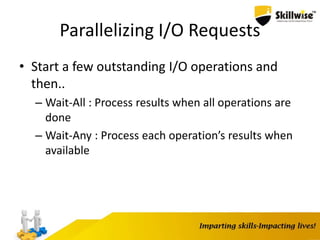

![Task.WhenAll

Task<string>[] tasks = new Task<string>[] {

m_http.GetStringAsync(url1),

m_http.GetStringAsync(url2),

m_http.GetStringAsync(url3)

};

Task<string[]> all = Task.WhenAll(tasks);

string[] results = await all;

// Process the results](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/enhancingdotnetapp-150923051627-lva1-app6892/85/Skillwise-Enhancing-dotnet-app-74-320.jpg)

![Task.WhenAny

List<Task<string>> tasks = new List<Task<string>>[] {

m_http.GetStringAsync(url1),

m_http.GetStringAsync(url2),

m_http.GetStringAsync(url3)

};

while (tasks.Count> 0)

{

Task<Task<string>> any = Task.WhenAny(tasks);

Task<string> completed = await any;

// Process the result in completed.Result

tasks.Remove(completed);

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/enhancingdotnetapp-150923051627-lva1-app6892/85/Skillwise-Enhancing-dotnet-app-75-320.jpg)