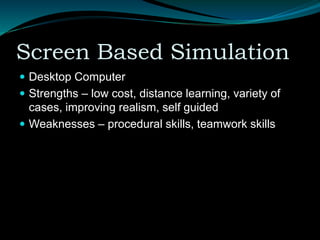

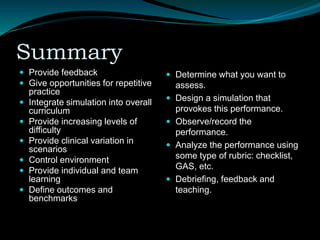

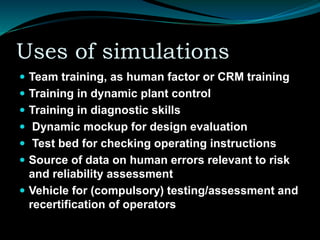

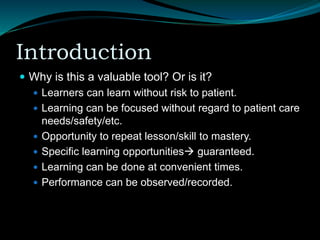

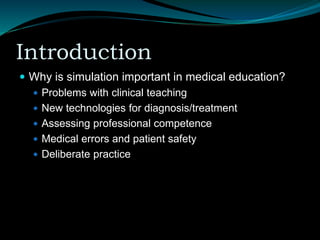

The document discusses the use of simulation in medical education, specifically for anesthetists, highlighting its importance in training without risking patient safety. It outlines various simulation modalities, their strengths and weaknesses, as well as best practices for integration into educational curricula. Additionally, it emphasizes the need for effective assessment methods to ensure competency in medical training.

![ Theory input (T): Most exercises have didactic

and theory components on relevant content

information. Sometimes this material is made

available in advance via readings or online

exercises.

Breaks (B): For complex courses (e.g.,

anesthesia crisis resource management

[ACRM]), breaks are important for socialization

between participants and with instructors. It also

is a venue for informal sharing and storytelling.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/86-240611084053-29f6e5aa/85/Simulators-in-Anaesthesia-the-future-and-past-15-320.jpg)