The document discusses various methods for linear modeling and variable selection, including the application of penalized regression techniques like ridge regression and the use of model selection criteria such as AIC and BIC. It emphasizes the importance of penalizing complex models to prevent overfitting, highlights estimation strategies, and compares classical and Bayesian perspectives on model fitting. Additionally, it covers the properties of ridge estimators and the singular value decomposition in the context of regression analysis.

![Arthur Charpentier, SIDE Summer School, July 2019

Linear Model and Variable Selection

In a linear model,

log L(β, σ2

) = −

n

2

log σ2

−

n

2

log(2π) −

1

2σ2

y − Xβ 2

and

log L(βs, σ2

s ) = −

n

2

log

RSS(s)

n

−

n

2

[1 + log(2π)]

It is necessary to penalize too complex models

Akaike’s AIC : AIC(s) =

n

2

log

RSS(s)

n

+

n

2

[1 + log(2π)] + 2|s|

Schwarz’s BIC : BIC(s) =

n

2

log

RSS(s)

n

+

n

2

[1 + log(2π)] + |s| log n

Exhaustive search of all models, 2p+1

... too complicated.

Stepwise procedure, forward or backward... not very stable and satisfactory.

@freakonometrics freakonometrics freakonometrics.hypotheses.org 3](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sidearthur2019preliminary03-190715221210/85/Side-2019-3-3-320.jpg)

![Arthur Charpentier, SIDE Summer School, July 2019

Linear Model and Variable Selection

For variable selection, use the classical stats::step function, or leaps::regsubset

for best subset, forward stepwide and backward stepwise.

For leave-one-out-cross validation, we can write

1

n

n

i=1

(yi − y(i))2

=

1

n

n

i=1

yi − yi

1 − Hi,i

2

Heuristically, (yi − yi)2

underestimates the true prediction error

High underestimation if the correlation between yi and yi is high

One can use Cov[y, y], e.g. in Mallows’ Cp,

Cp =

1

n

n

i=1

(yi − yi)2

+

2

n

σ2

p where p =

1

σ2

trace[Cov(y, y])

with Gaussian errors, AIC and Mallows’ Cp are asymptotically equivalent.

@freakonometrics freakonometrics freakonometrics.hypotheses.org 4](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sidearthur2019preliminary03-190715221210/85/Side-2019-3-4-320.jpg)

![Arthur Charpentier, SIDE Summer School, July 2019

Linear Regression Shortcoming

Least Squares Estimator β = (XT

X)−1

XT

y

Unbiased Estimator E[β] = β

Variance Var[β] = σ2

(XT

X)−1

which can be (extremely) large when det[(XT

X)] ∼ 0.

X =

1 −1 2

1 0 1

1 2 −1

1 1 0

then XT

X =

4 2 2

2 6 −4

2 −4 6

while XT

X+I =

5 2 2

2 7 −4

2 −4 7

eigenvalues : {10, 6, 0} {11, 7, 1}

Ad-hoc strategy: use XT

X + λI

@freakonometrics freakonometrics freakonometrics.hypotheses.org 7](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sidearthur2019preliminary03-190715221210/85/Side-2019-3-7-320.jpg)

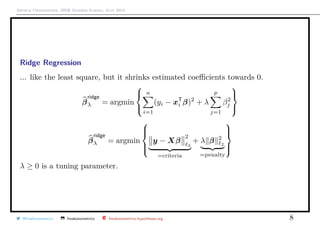

![Arthur Charpentier, SIDE Summer School, July 2019

Ridge Regression

Observe that if xj1

⊥ xj2

, then

β

ridge

λ = [1 + λ]−1

β

ols

λ

which explain relationship with shrinkage.

But generally, it is not the case...

Smaller mse

There exists λ such that mse[β

ridge

λ ] ≤ mse[β

ols

λ ]

q

q

@freakonometrics freakonometrics freakonometrics.hypotheses.org 12](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sidearthur2019preliminary03-190715221210/85/Side-2019-3-12-320.jpg)

![Arthur Charpentier, SIDE Summer School, July 2019

The Bayesian Interpretation

From a Bayesian perspective,

P[θ|y]

posterior

∝ P[y|θ]

likelihood

· P[θ]

prior

i.e. log P[θ|y] = log P[y|θ]

log likelihood

+ log P[θ]

penalty

If β has a prior N(0, τ2

I) distribution, then its posterior distribution has mean

E[β|y, X] = XT

X +

σ2

τ2

I

−1

XT

y.

@freakonometrics freakonometrics freakonometrics.hypotheses.org 14](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sidearthur2019preliminary03-190715221210/85/Side-2019-3-14-320.jpg)

![Arthur Charpentier, SIDE Summer School, July 2019

Properties of the Ridge Estimator

βλ = (XT

X + λI)−1

XT

y

E[βλ] = XT

X(λI + XT

X)−1

β.

i.e. E[βλ] = β.

Observe that E[βλ] → 0 as λ → ∞.

Ridge & Shrinkage

Assume that X is an orthogonal design matrix, i.e. XT

X = I, then

βλ = (1 + λ)−1

β

ols

.

@freakonometrics freakonometrics freakonometrics.hypotheses.org 15](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sidearthur2019preliminary03-190715221210/85/Side-2019-3-15-320.jpg)

![Arthur Charpentier, SIDE Summer School, July 2019

Properties of the Ridge Estimator

Set W λ = (I + λ[XT

X]−1

)−1

. One can prove that

W λβ

ols

= βλ.

Thus,

Var[βλ] = W λVar[β

ols

]W T

λ

and

Var[βλ] = σ2

(XT

X + λI)−1

XT

X[(XT

X + λI)−1

]T

.

Observe that

Var[β

ols

] − Var[βλ] = σ2

W λ[2λ(XT

X)−2

+ λ2

(XT

X)−3

]W T

λ ≥ 0.

@freakonometrics freakonometrics freakonometrics.hypotheses.org 16](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sidearthur2019preliminary03-190715221210/85/Side-2019-3-16-320.jpg)

![Arthur Charpentier, SIDE Summer School, July 2019

Properties of the Ridge Estimator

Hence, the confidence ellipsoid of ridge estimator is

indeed smaller than the OLS,

If X is an orthogonal design matrix,

Var[βλ] = σ2

(1 + λ)−2

I.

mse[βλ] = σ2

trace(W λ(XT

X)−1

W T

λ) + βT

(W λ − I)T

(W λ − I)β.

If X is an orthogonal design matrix,

mse[βλ] =

pσ2

(1 + λ)2

+

λ2

(1 + λ)2

βT

β

@freakonometrics freakonometrics freakonometrics.hypotheses.org 17

0.0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8

−1.0−0.8−0.6−0.4−0.2

β1

β2

1

2

3

4

5

6

7](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sidearthur2019preliminary03-190715221210/85/Side-2019-3-17-320.jpg)

![Arthur Charpentier, SIDE Summer School, July 2019

Properties of the Ridge Estimator

mse[βλ] =

pσ2

(1 + λ)2

+

λ2

(1 + λ)2

βT

β

is minimal for

λ =

pσ2

βT

β

Note that there exists λ > 0 such that mse[βλ] < mse[β0] = mse[β

ols

].

Ridge regression is obtained using glmnet::glmnet(..., alpha = 0) - and

glmnet::cv.glmnet for cross validation

@freakonometrics freakonometrics freakonometrics.hypotheses.org 18](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sidearthur2019preliminary03-190715221210/85/Side-2019-3-18-320.jpg)

![Arthur Charpentier, SIDE Summer School, July 2019

Hat matrix and Degrees of Freedom

Recall that Y = HY with

H = X(XT

X)−1

XT

Similarly

Hλ = X(XT

X + λI)−1

XT

trace[Hλ] =

p

j=1

d2

j,j

d2

j,j + λ

→ 0, as λ → ∞.

@freakonometrics freakonometrics freakonometrics.hypotheses.org 21](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sidearthur2019preliminary03-190715221210/85/Side-2019-3-21-320.jpg)

![Arthur Charpentier, SIDE Summer School, July 2019

Going further on sparsity issues

On [−1, +1]k

, the convex hull of β 0

is β 1

On [−a, +a]k

, the convex hull of β 0

is a−1

β 1

Hence, why not solve

β = argmin

β; β 1 ≤˜s

{ Y − XT

β 2 }

which is equivalent (Kuhn-Tucker theorem) to the Lagragian optimization

problem

β = argmin{ Y − XT

β 2

2

+λ β 1

}

@freakonometrics freakonometrics freakonometrics.hypotheses.org 26](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sidearthur2019preliminary03-190715221210/85/Side-2019-3-26-320.jpg)

![Arthur Charpentier, SIDE Summer School, July 2019

Optimal lasso Penalty

Use cross validation, e.g. K-fold,

β(−k)(λ) = argmin

i∈Ik

[yi − xT

i β]2

+ λ β 1

then compute the sum of the squared errors,

Qk(λ) =

i∈Ik

[yi − xT

i β(−k)(λ)]2

and finally solve

λ = argmin Q(λ) =

1

K

k

Qk(λ)

@freakonometrics freakonometrics freakonometrics.hypotheses.org 31](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sidearthur2019preliminary03-190715221210/85/Side-2019-3-31-320.jpg)

![Arthur Charpentier, SIDE Summer School, July 2019

Optimal lasso Penalty

Note that this might overfit, so Hastie, Tibshiriani & Friedman (2009, Elements

of Statistical Learning) suggest the largest λ such that

Q(λ) ≤ Q(λ ) + se[λ ] with se[λ]2

=

1

K2

K

k=1

[Qk(λ) − Q(λ)]2

lasso regression is obtained using glmnet::glmnet(..., alpha = 1) - and

glmnet::cv.glmnet for cross validation.

@freakonometrics freakonometrics freakonometrics.hypotheses.org 32](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sidearthur2019preliminary03-190715221210/85/Side-2019-3-32-320.jpg)

![Arthur Charpentier, SIDE Summer School, July 2019

LASSO and Ridge, with R

1 > library(glmnet)

2 > chicago=read.table("http:// freakonometrics .free.fr/

chicago.txt",header=TRUE ,sep=";")

3 > standardize <- function(x) {(x-mean(x))/sd(x)}

4 > z0 <- standardize(chicago[, 1])

5 > z1 <- standardize(chicago[, 3])

6 > z2 <- standardize(chicago[, 4])

7 > ridge <-glmnet(cbind(z1 , z2), z0 , alpha =0, intercept=

FALSE , lambda =1)

8 > lasso <-glmnet(cbind(z1 , z2), z0 , alpha =1, intercept=

FALSE , lambda =1)

9 > elastic <-glmnet(cbind(z1 , z2), z0 , alpha =.5,

intercept=FALSE , lambda =1)

Elastic net, λ1 β 1 + λ2 β 2

2

q

q

q

qqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqq

q

q

qq

q

q

qqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqq

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

qqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqq

q

q

q

q

q

qq

q

q

q

q

q

qqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqq

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

qqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqq

q

q

qq

q

q

qqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqq

q

q

q

@freakonometrics freakonometrics freakonometrics.hypotheses.org 33](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sidearthur2019preliminary03-190715221210/85/Side-2019-3-33-320.jpg)

![Arthur Charpentier, SIDE Summer School, July 2019

lasso and lar (Least-Angle Regression)

lasso estimation can be seen as an adaptation of LAR procedure

Least Angle Regression

(i) set (small)

(ii) start with initial residual ε = y, and β = 0

(iii) find the predictor xj with the highest correlation with ε

(iv) update βj = βj + δj = βj + · sign[ε xj]

(v) set ε = ε − δjxj and go to (iii)

see Efron et al. (2004, Least Angle Regression)

@freakonometrics freakonometrics freakonometrics.hypotheses.org 34](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sidearthur2019preliminary03-190715221210/85/Side-2019-3-34-320.jpg)

![Arthur Charpentier, SIDE Summer School, July 2019

Going further, 0, 1 and 2 penalty

Foster & George (1994) the risk inflation criterion for multiple regression tried to

solve directly the penalized problem of ( 0).

But it is a complex combinatorial problem in high dimension (Natarajan (1995)

sparse approximate solutions to linear systems proved that it was a NP-hard

problem)

One can prove that if λ ∼ σ2

log(p), alors

E [xT

β − xT

β0]2

≤ E [xS

T

βS − xT

β0]2

=σ2#S

· 4 log p + 2 + o(1) .

In that case

β

sub

λ,j =

0 si j /∈ Sλ(β)

β

ols

j si j ∈ Sλ(β),

where Sλ(β) is the set of non-null values in solutions of ( 0).

@freakonometrics freakonometrics freakonometrics.hypotheses.org 37](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sidearthur2019preliminary03-190715221210/85/Side-2019-3-37-320.jpg)

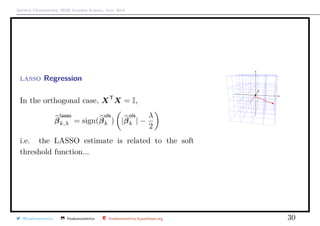

![Arthur Charpentier, SIDE Summer School, July 2019

Going further, 0, 1 and 2 penalty

Thus, lasso can be used for variable selection - see Hastie et al. (2001, The

Elements of Statistical Learning).

Generally, βlasso

λ is a biased estimator but its variance can be small enough to

have a smaller least squared error than the OLS estimate.

With orthonormal covariates, one can prove that

βsub

λ,j = βols

j 1|βsub

λ,j

|>b

, βridge

λ,j =

βols

j

1 + λ

and βlasso

λ,j = signe[βols

j ] · (|βols

j | − λ)+.

@freakonometrics freakonometrics freakonometrics.hypotheses.org 42](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sidearthur2019preliminary03-190715221210/85/Side-2019-3-42-320.jpg)

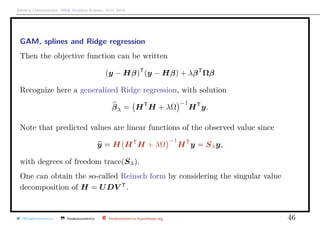

![Arthur Charpentier, SIDE Summer School, July 2019

GAM, splines and Ridge regression

Consider a univariate nonlinear regression problem, so that E[Y |X = x] = m(x).

Given a sample {(y1, x1), · · · , (yn, xn)}, consider the following penalized problem

m = argmin

m∈C2

n

i=1

(yi − m(xi))2

+ λ

R

m (x)dx

with the Residual sum of squares on the left, and a penalty for the roughness of

the function.

The solution is a natural cubic spline with knots at unique values of x (see

Eubanks (1999, Nonparametric Regression and Spline Smoothing)

Consider some spline basis {h1, · · · , hn}, and let m(x) =

n

i=1

βihi(x).

Let H and Ω be the n × n matrices Hi,j = hj(xi), and Ωi,j =

R

hi (x)hj (x)dx.

@freakonometrics freakonometrics freakonometrics.hypotheses.org 45](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sidearthur2019preliminary03-190715221210/85/Side-2019-3-45-320.jpg)

![Arthur Charpentier, SIDE Summer School, July 2019

From LASSO to Group Lasso

Assume that variables x ∈ Rp

can be grouped in L subgroups, x = (x1 · · · , xL),

where dim[xl] = pl.

Yuan & Lin (2007, Model selection and estimation in the Gaussian graphical model)

defined, for some Kl matrices nl × nl definite positives

β

g-lasso

λ ∈ argmin

β∈Rp

y − Xβ 2

2

+ λ

L

l=1

βl Klβl

or, if Kl = plI

β

g-lasso

λ ∈ argmin

β∈Rp

y − Xβ 2

2

+ λ

L

l=1

pl βl 2

See library gglasso

@freakonometrics freakonometrics freakonometrics.hypotheses.org 54](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sidearthur2019preliminary03-190715221210/85/Side-2019-3-54-320.jpg)

![Arthur Charpentier, SIDE Summer School, July 2019

From LASSO to Sparse-Group Lasso

Assume that variables x ∈ Rp

can be grouped in L subgroups, x = (x1 · · · , xL),

where dim[xl] = pl.

Simon et al. (2013, A Sparse-Group LASSO) defined, for some Kl matrices nl × nl

definite positives

β

sg-lasso

λ,µ ∈ argmin

β∈Rp

y − Xβ 2

2

+ λ

L

l=1

βl Klβl + µ β 1

See library SGL

@freakonometrics freakonometrics freakonometrics.hypotheses.org 55](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sidearthur2019preliminary03-190715221210/85/Side-2019-3-55-320.jpg)