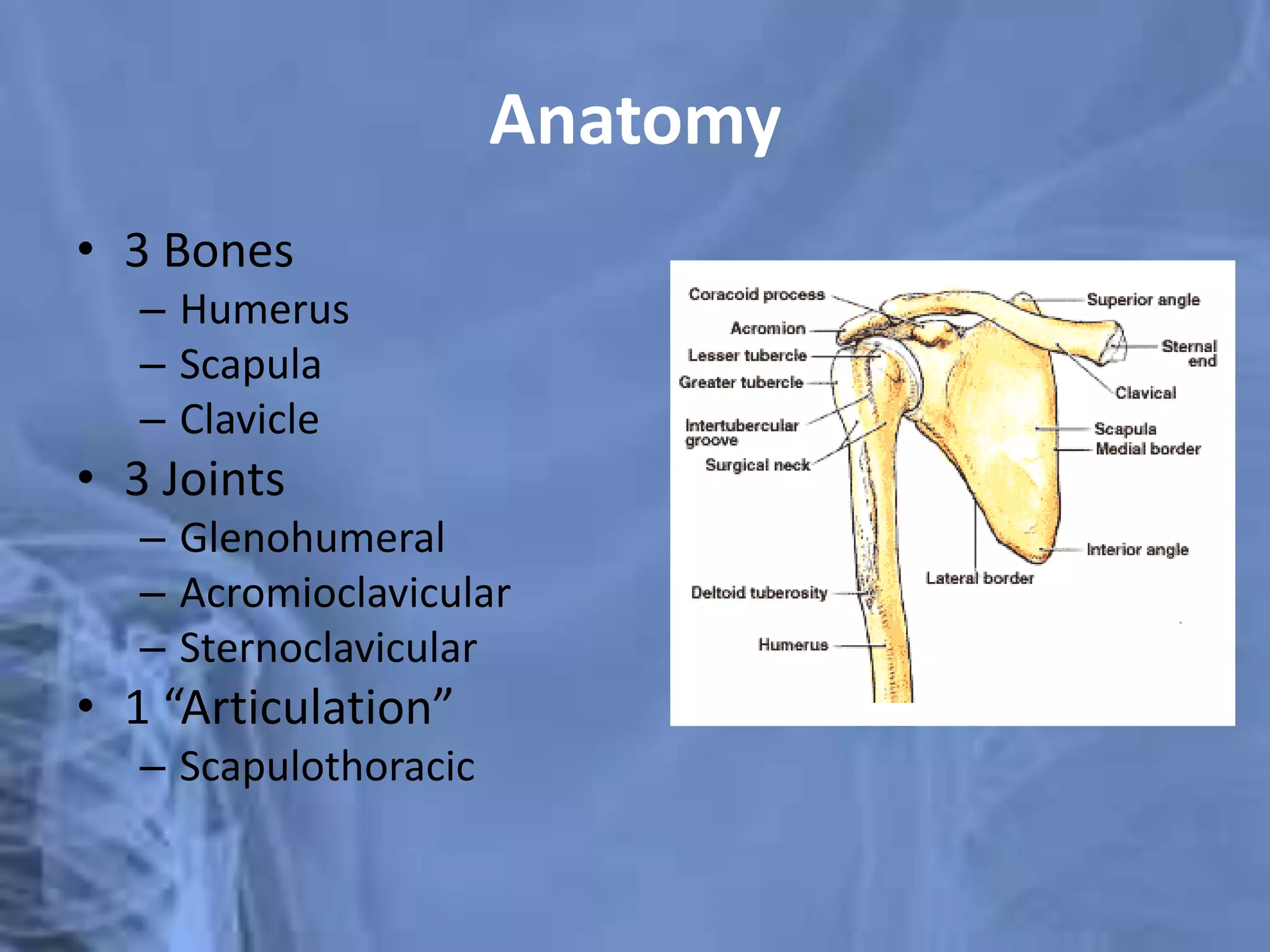

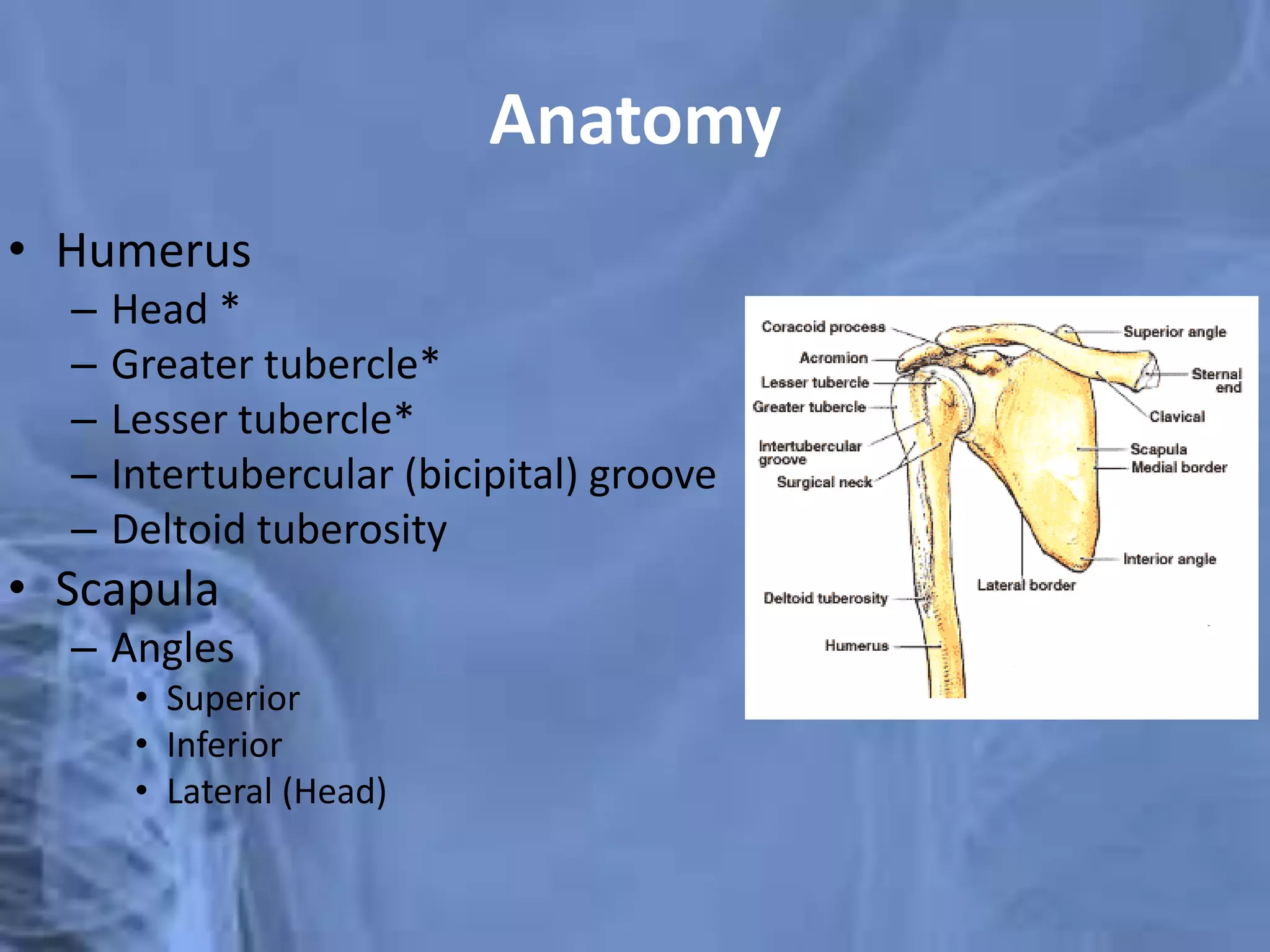

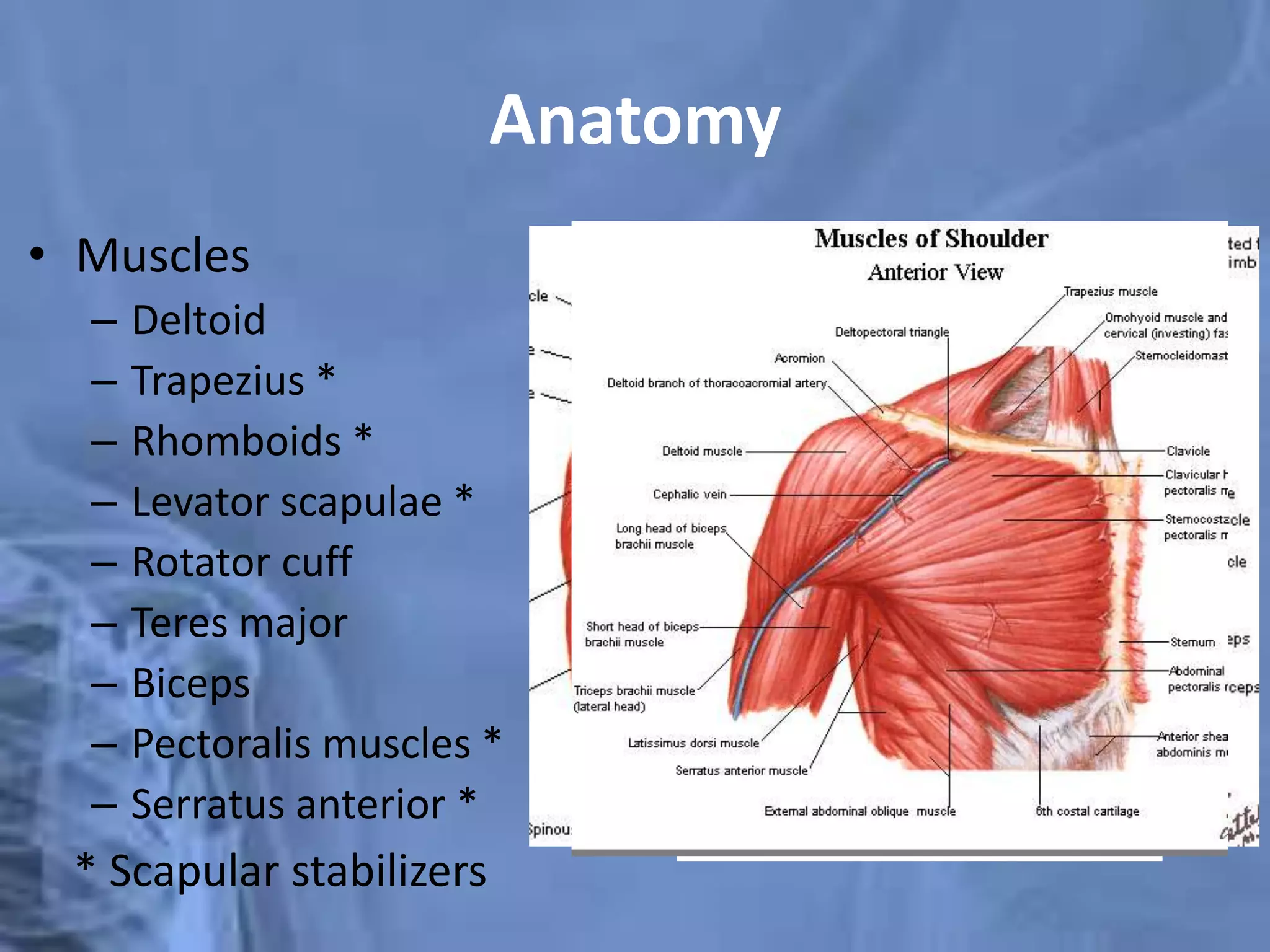

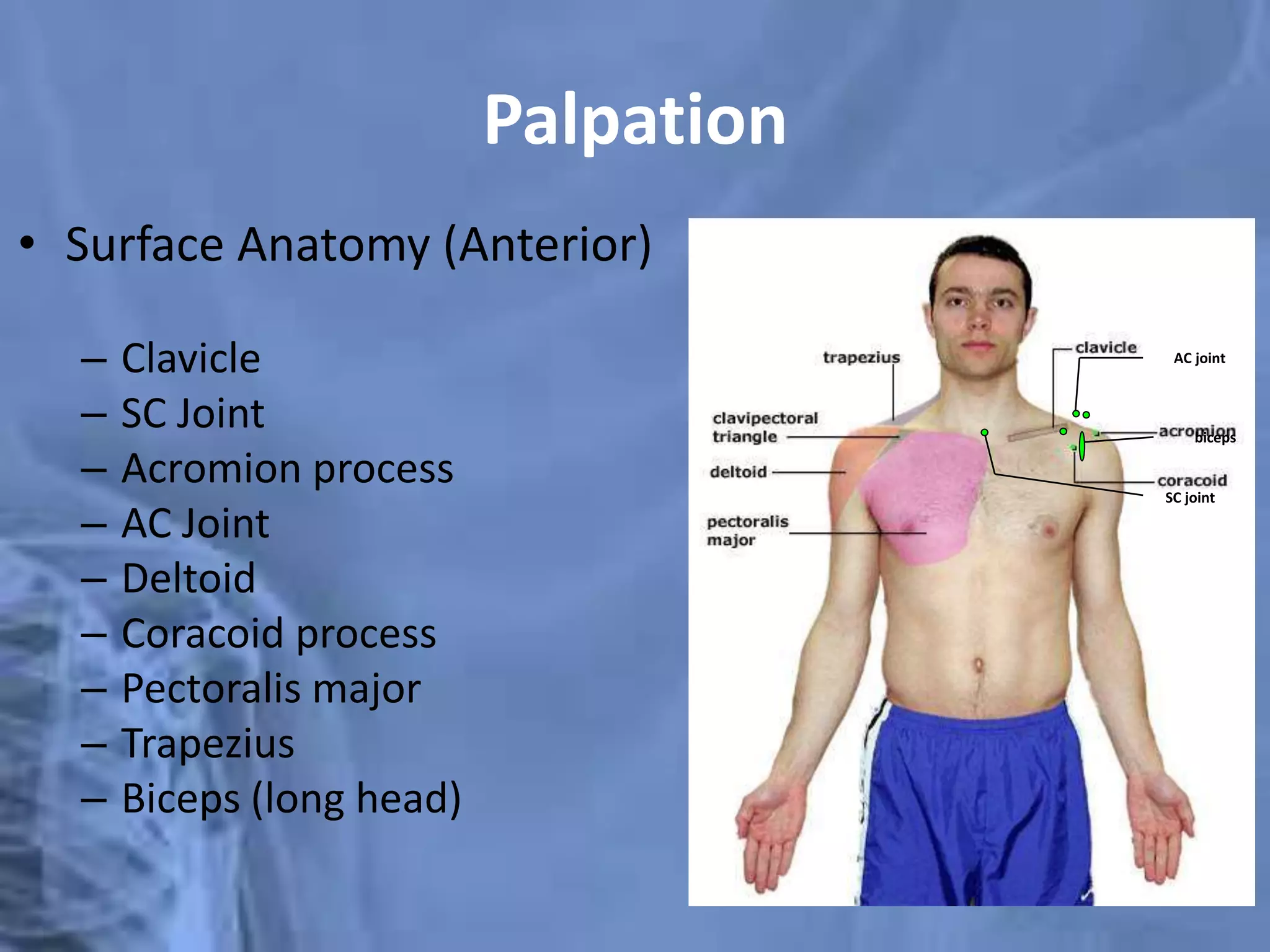

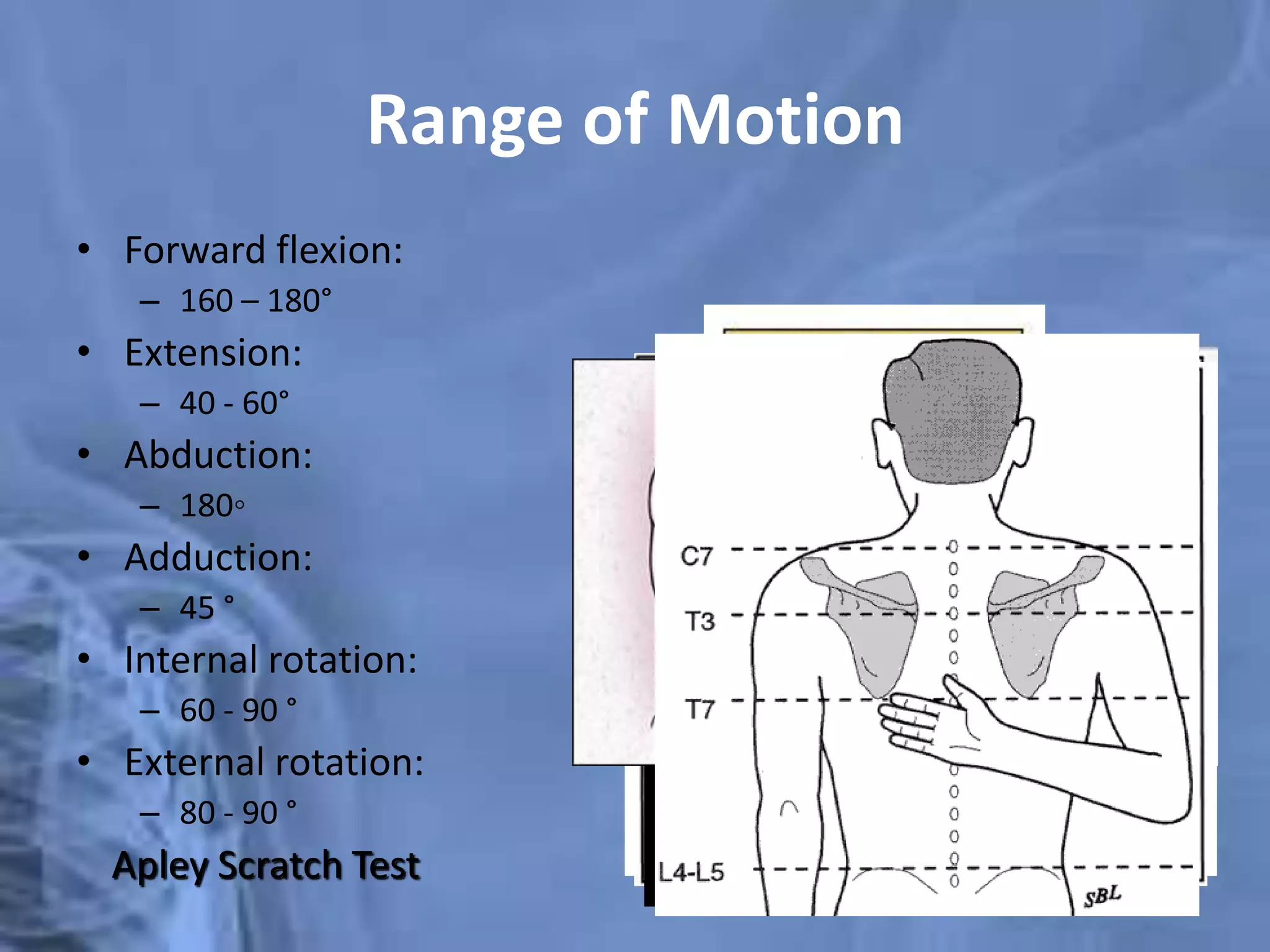

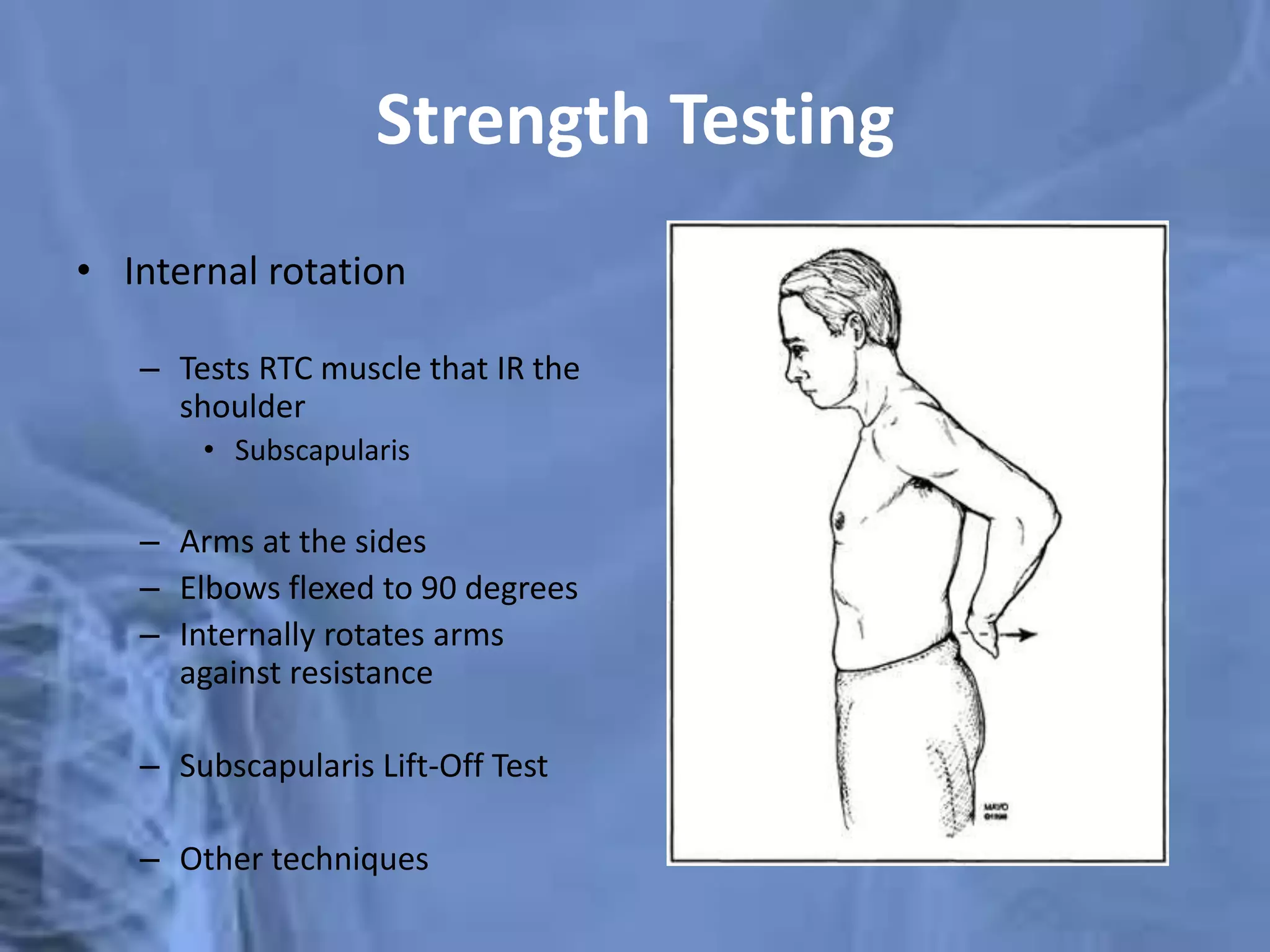

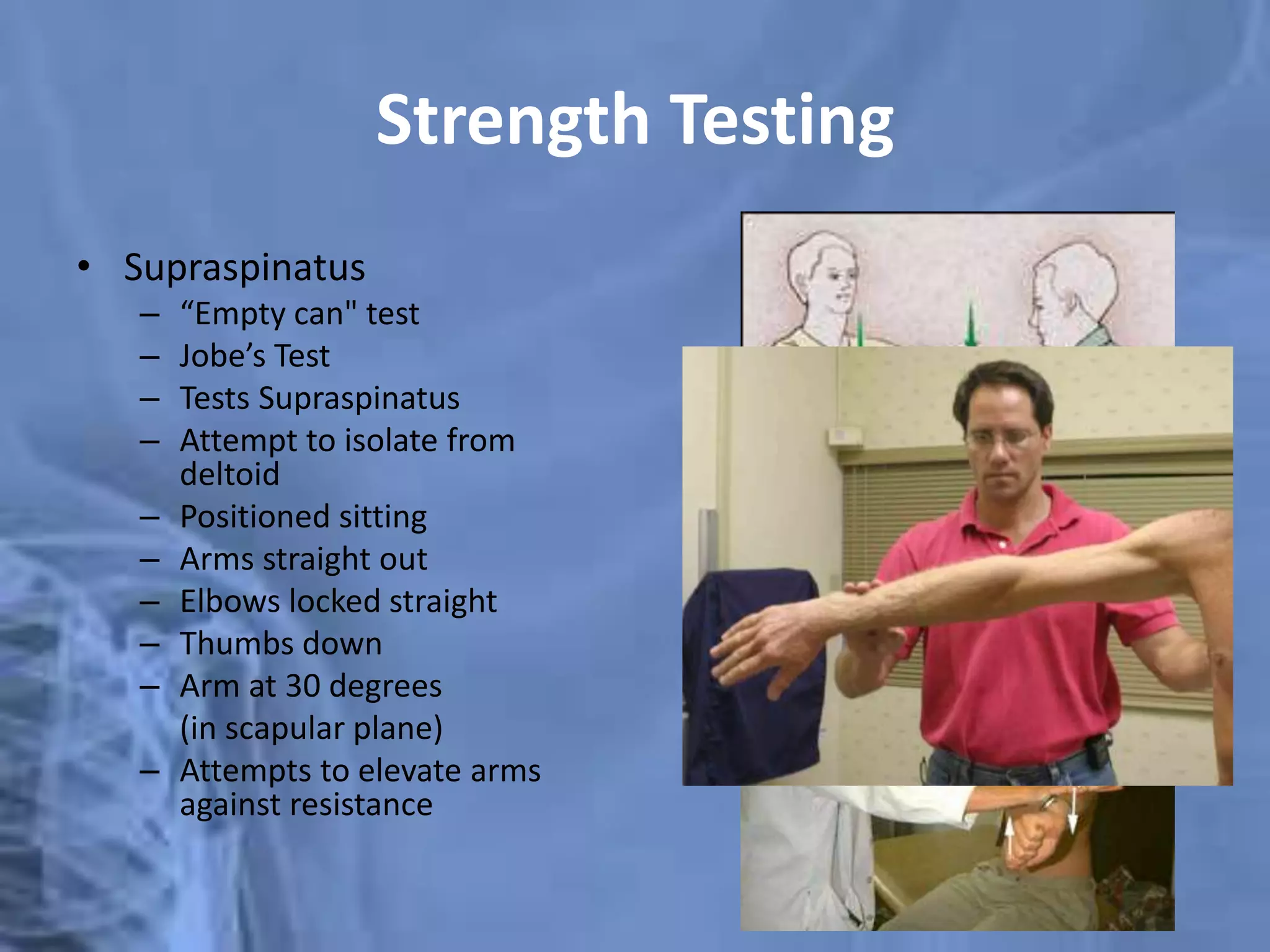

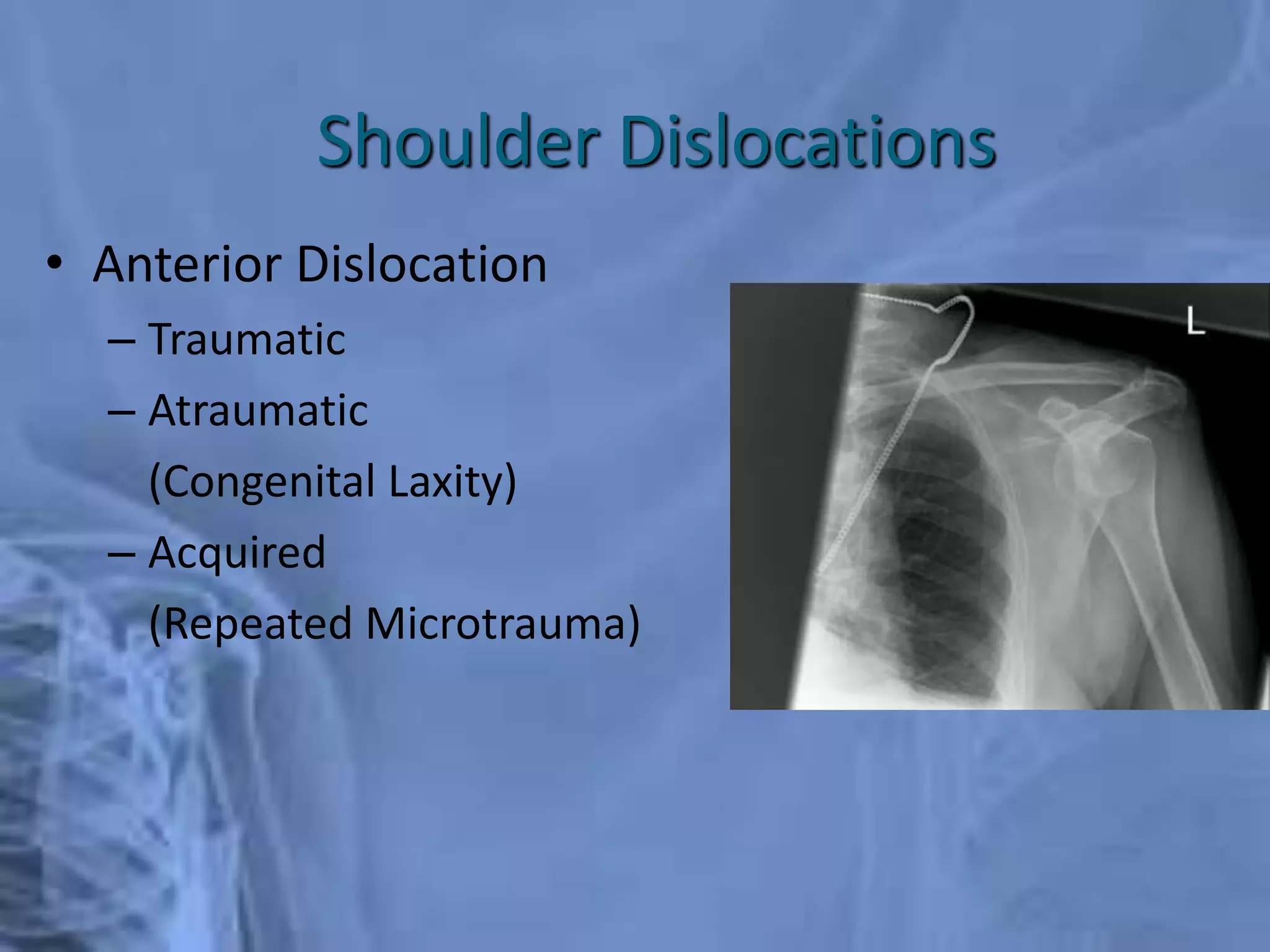

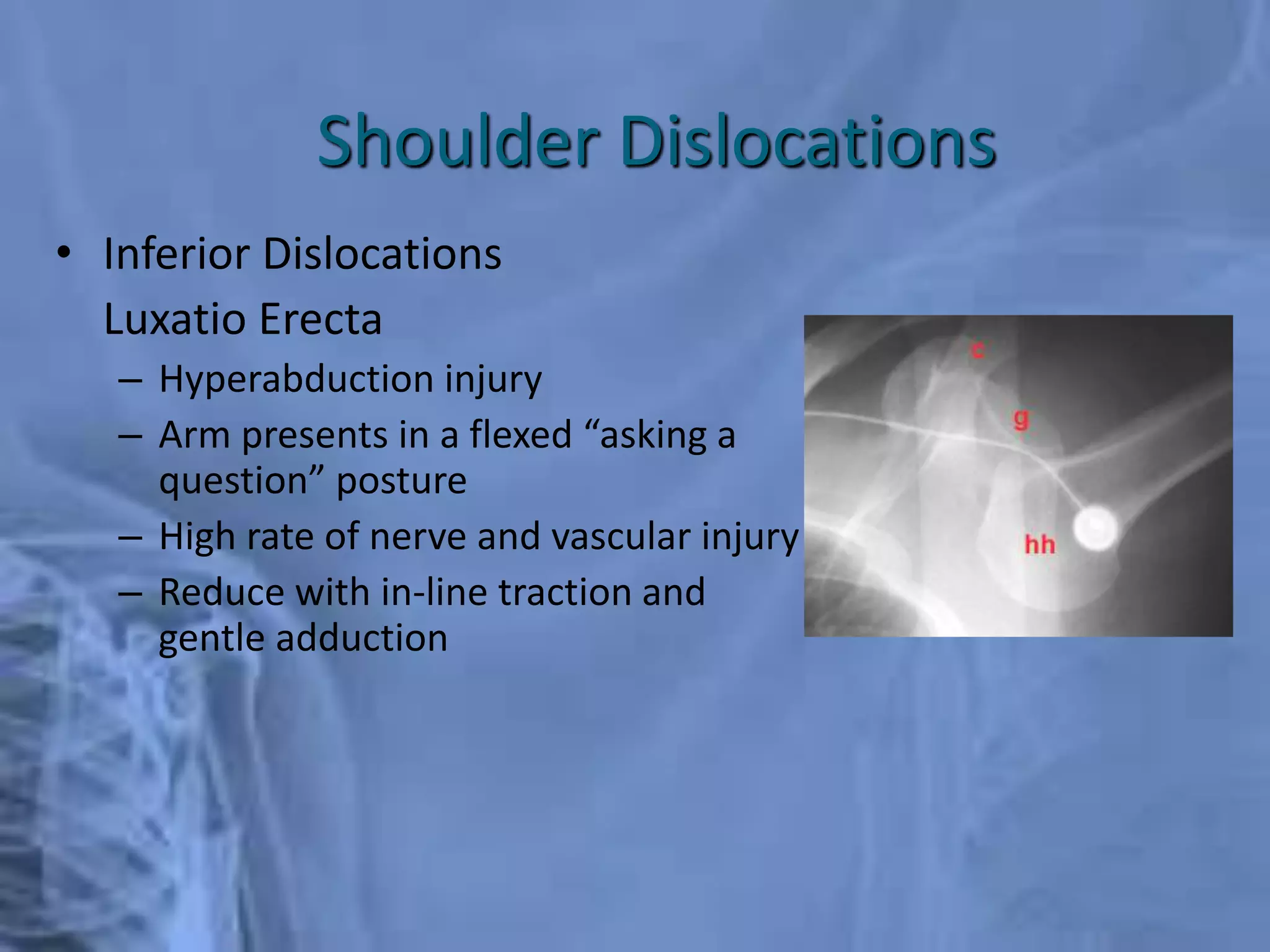

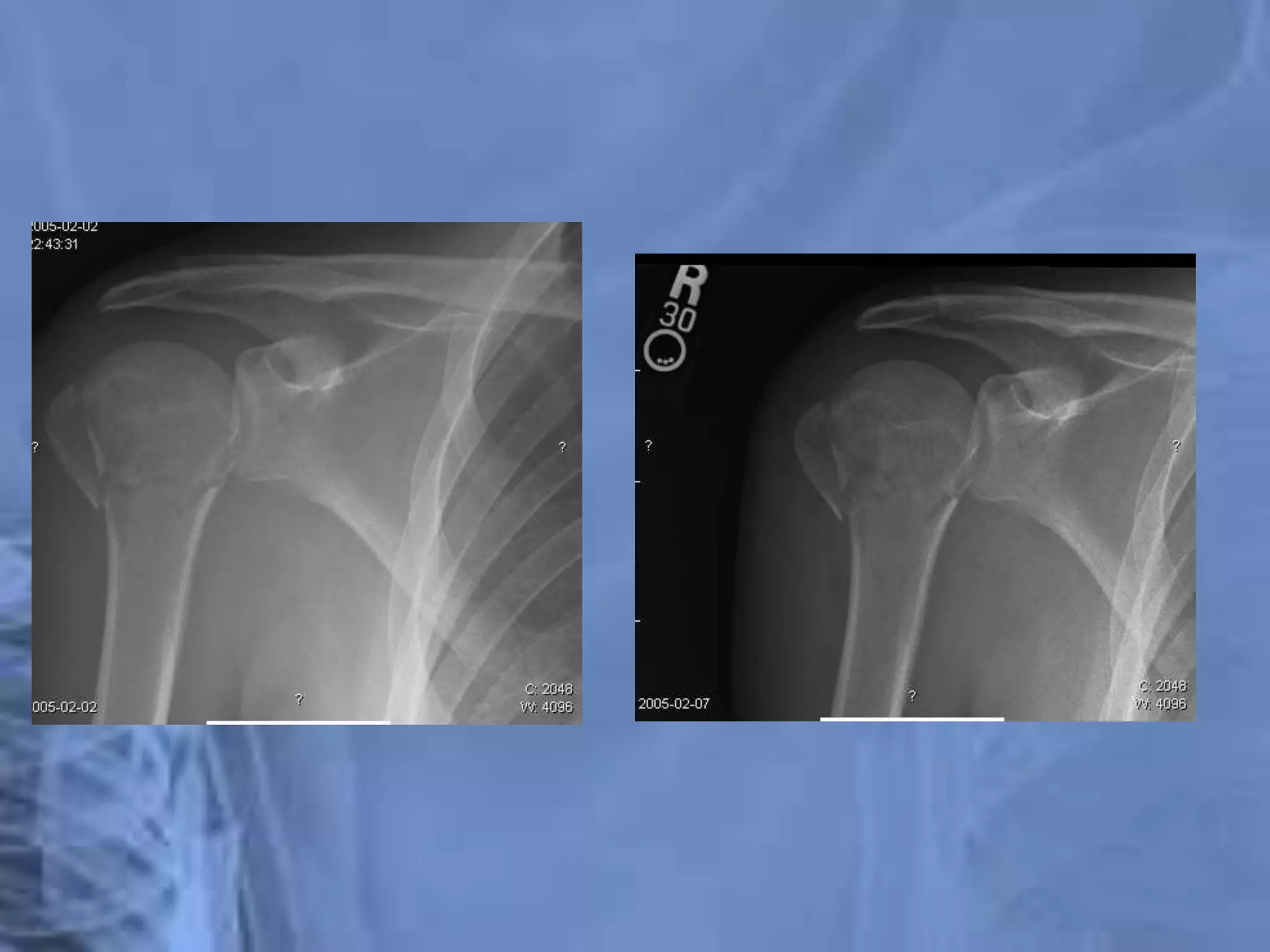

This document provides an overview of shoulder anatomy and common shoulder injuries. It begins with brief epidemiology of shoulder pain, noting that shoulder injuries are common in adults ages 40-60. It then details the anatomy of the shoulder joint, including the bones, joints, muscles, nerves and vascular structures. The document outlines common differential diagnoses for shoulder pain and provides guidance on clinical history and physical exam. It concludes with sections on specific shoulder injuries like fractures of the clavicle and proximal humerus, shoulder dislocations, and treatment approaches.