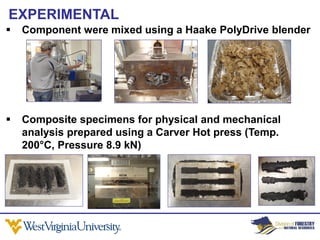

1. The researchers combined biochar, wood flour, and polypropylene to create novel wood-plastic composites (WPCs) and tested their mechanical and physical properties.

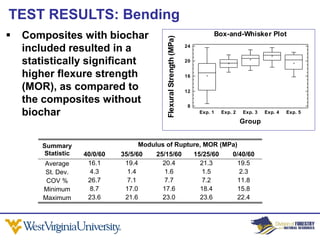

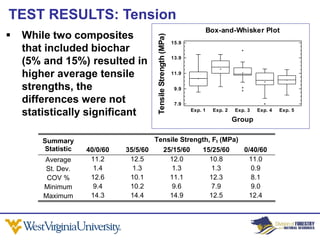

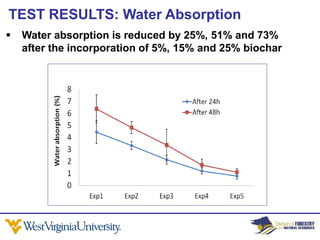

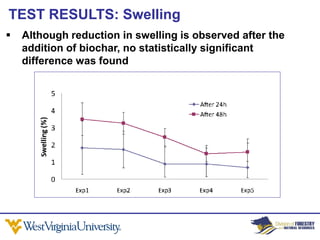

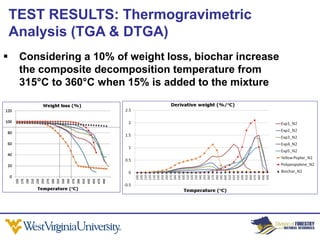

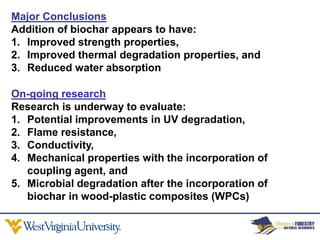

2. Adding biochar improved the composites' strength properties, thermal degradation resistance, and reduced water absorption. Composites with 15% biochar showed the highest flexural strength and decomposition temperature.

3. Ongoing research is evaluating how biochar affects other properties like UV degradation resistance, flame resistance, conductivity, and mechanical properties with coupling agents.