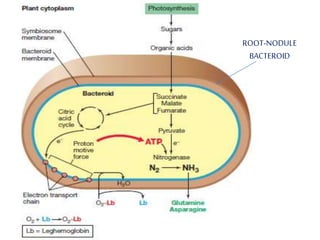

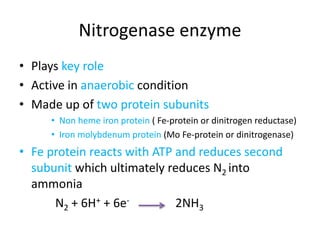

Rhizobium is a genus of nitrogen-fixing bacteria that forms symbiotic root nodules on legume plants. The bacteria live within the nodules and convert atmospheric nitrogen into ammonia, which is provided to the plant in exchange for organic compounds from photosynthesis. Key to this process is the nitrogenase enzyme, which consists of an iron and molybdenum-iron protein that work together to reduce dinitrogen gas into ammonia. The nodules also contain leghemoglobin, which protects the oxygen-sensitive nitrogenase enzyme. This mutually beneficial relationship between Rhizobium bacteria and legumes provides fixed nitrogen to the plants.

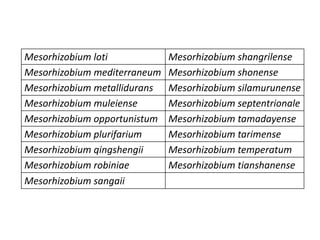

![Legume family

Plants that contribute to nitrogen fixation include the legume family – Fabaceae –

with taxa such as kudzu, clovers, soybeans, alfalfa, lupines, peanuts, and rooibos.

They contain symbiotic bacteria called rhizobia within the nodules, producing

nitrogen compounds that help the plant to grow and compete with other plants.

When the plant dies, the fixed nitrogen is released, making it available to other

plants and this helps to fertilize the soil.

The great majority of legumes have this association, but a few genera

(e.g.,Styphnolobium) do not.

In many traditional and organic farming practices, fields are rotated through

various types of crops, which usually includes one consisting mainly or entirely of

clover or buckwheat (non-legume family Polygonaceae), which are often referred

to as "green manure".

Inga alley farming relies on the leguminous genus Inga, a small tropical, tough-

leaved, nitrogen-fixing tree.[4]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/rhizobiumppt-170630063757/85/Rhizobium-ppt-51-320.jpg)

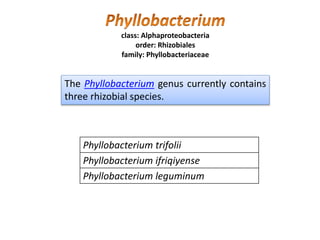

![Nodulation is controlled by a variety of processes, both external (heat, acidic

soils, drought, nitrate) and internal (autoregulation of nodulation, ethylene).

Autoregulation of nodulation controls nodule numbers per plant through a

systemic process involving the leaf. Leaf tissue senses the early nodulation

events in the root through an unknown chemical signal, then restricts further

nodule development in newly developing root tissue.

The Leucine rich repeat (LRR) receptor kinases (NARK in soybean (Glycine

max); HAR1 in Lotus japonicus, SUNN in Medicago truncatula) are essential

for autoregulation of nodulation (AON). Mutation leading to loss of function

in these AON receptor kinases leads to supernodulation or hypernodulation.

Often root growth abnormalities accompany the loss of AON receptor kinase

activity, suggesting that nodule growth and root development are

functionally linked. Investigations into the mechanisms of nodule formation

showed that theENOD40 gene, coding for a 12–13 amino acid protein [41], is

up-regulated during nodule formation [3].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/rhizobiumppt-170630063757/85/Rhizobium-ppt-61-320.jpg)