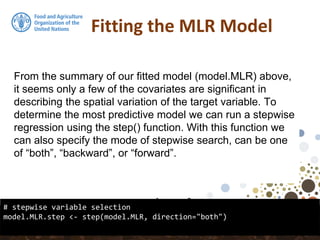

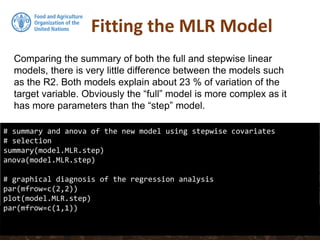

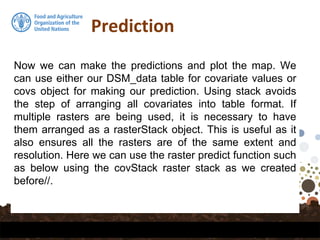

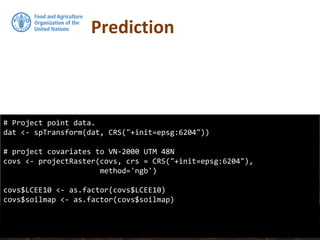

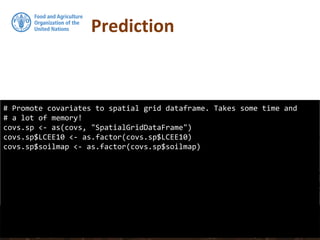

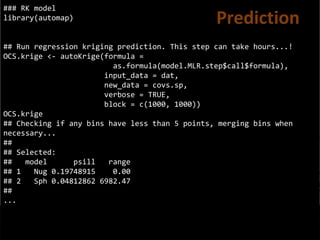

The document outlines a training program for digital soil organic carbon mapping using regression-kriging, a spatial interpolation technique that integrates regression modeling with kriging. It details the workflow for mapping soil properties, including data preparation, model fitting using multiple linear regression, and assessing model validity through residual analysis and collinearity checks. The document culminates in predicting soil carbon values and generating raster outputs for visualization and analysis.

![Regression Kriging

library(sp)

# Promote to spatialPointsDataFrame

coordinates(dat) <- ~ X + Y

class(dat)

## [1] "SpatialPointsDataFrame"

## attr(,"package")

## [1] "sp"

Since we will be working with spatial data we need to define

the coordinates for the imported data. Using the coordinates()

function from the sp package we can define the columns in the

data frame to refer to spatial coordinates—here the coordinates

are listed in columns X and Y.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ird42-regressionkriging-180321133151/85/Regression-kriging-20-320.jpg)

![Covariates

library(raster)

# list all the itf files in the folder covs/

files <- list.files(path = "covs", pattern = "tif$",

full.names = TRUE)

# load all the tif files in one rasterStack object

covs <- stack(files)

# load the vectorial version of the soil map

soilmap <- shapefile("MK_soilmap_simple.shp")

# rasterize using the Symbol layer

soilmap@data$Symbol <- as.factor(soilmap@data$Symbol)

soilmap.r <- rasterize(x = soilmap, y = covs[[1]], field = "Symbol")](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ird42-regressionkriging-180321133151/85/Regression-kriging-24-320.jpg)

![Covariates

# stack the soil map and the other covariates

covs <- stack(covs, soilmap.r)

# correct the name for layer 14

names(covs)[14] <- "soilmap"

# print the names of the 14 layers:

names(covs)

## [1] "B04CHE3" "B07CHE3" "B13CHE3" "B14CHE3" "DEMENV5" "LCEE10"

## [7] "PRSCHE3" "SLPMRG5" "TMDMOD3" "TMNMOD3" "TWIMRG5" "VBFMRG5"

## [13] "VDPMRG5" "soilmap"](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ird42-regressionkriging-180321133151/85/Regression-kriging-25-320.jpg)

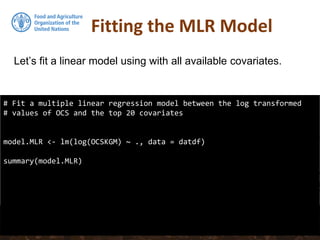

![Fitting the MLR Model

datdf <- dat@data

datdf <- datdf[, c("OCSKGM", names(covs))]

It would be better to progress with a data frame of just the

data and covariates required for the modelling. In this case,

we will subset the columns SOC, the covariates and the the

spatial coordinates (X and Y).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ird42-regressionkriging-180321133151/85/Regression-kriging-26-320.jpg)

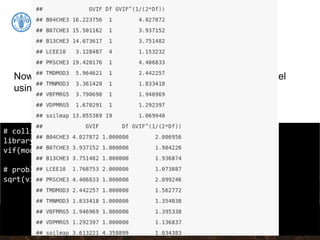

![Collinearity

# Removing B07CHE3 from the stepwise model:

model.MLR.step <- update(model.MLR.step, . ~ . - B07CHE3)

# Test the vif again:

sqrt(vif(model.MLR.step))

# summary of the new model using stepwise covariates selection

summary(model.MLR.step)

collinear: Temperature seasonality at 1 km (B04CHE3) and

Temperature Annual Range [°C] at 1 km (B07CHE3)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ird42-regressionkriging-180321133151/85/Regression-kriging-34-320.jpg)

![## Convert prediction and standard deviation to rasters

#

# And back-tansform the vlaues

RKprediction <- exp(raster(OCS.krige$krige_output[1]))

RKpredsd <- exp(raster(OCS.krige$krige_output[3]))

plot(RKprediction)

Prediction](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ird42-regressionkriging-180321133151/85/Regression-kriging-39-320.jpg)

![## Convert prediction and standard deviation to rasters

#

# And back-tansform the vlaues

RKprediction <- exp(raster(OCS.krige$krige_output[1]))

RKpredsd <- exp(raster(OCS.krige$krige_output[3]))

plot(RKprediction)

Prediction](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ird42-regressionkriging-180321133151/85/Regression-kriging-40-320.jpg)

![## Convert prediction and standard deviation to rasters

#

# And back-tansform the vlaues

RKprediction <- exp(raster(OCS.krige$krige_output[1]))

RKpredsd <- exp(raster(OCS.krige$krige_output[3]))

plot(RKprediction)

plot(RKpredsd)

Standard Dev](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ird42-regressionkriging-180321133151/85/Regression-kriging-41-320.jpg)

![## Convert prediction and standard deviation to rasters

#

# And back-tansform the vlaues

RKprediction <- exp(raster(OCS.krige$krige_output[1]))

RKpredsd <- exp(raster(OCS.krige$krige_output[3]))

plot(RKprediction)

plot(RKpredsd)

Standard Dev](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ird42-regressionkriging-180321133151/85/Regression-kriging-42-320.jpg)

![## Convert prediction and standard deviation to rasters

#

# And back-tansform the vlaues

RKprediction <- exp(raster(OCS.krige$krige_output[1]))

RKpredsd <- exp(raster(OCS.krige$krige_output[3]))

plot(RKprediction)

plot(RKpredsd)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ird42-regressionkriging-180321133151/85/Regression-kriging-43-320.jpg)