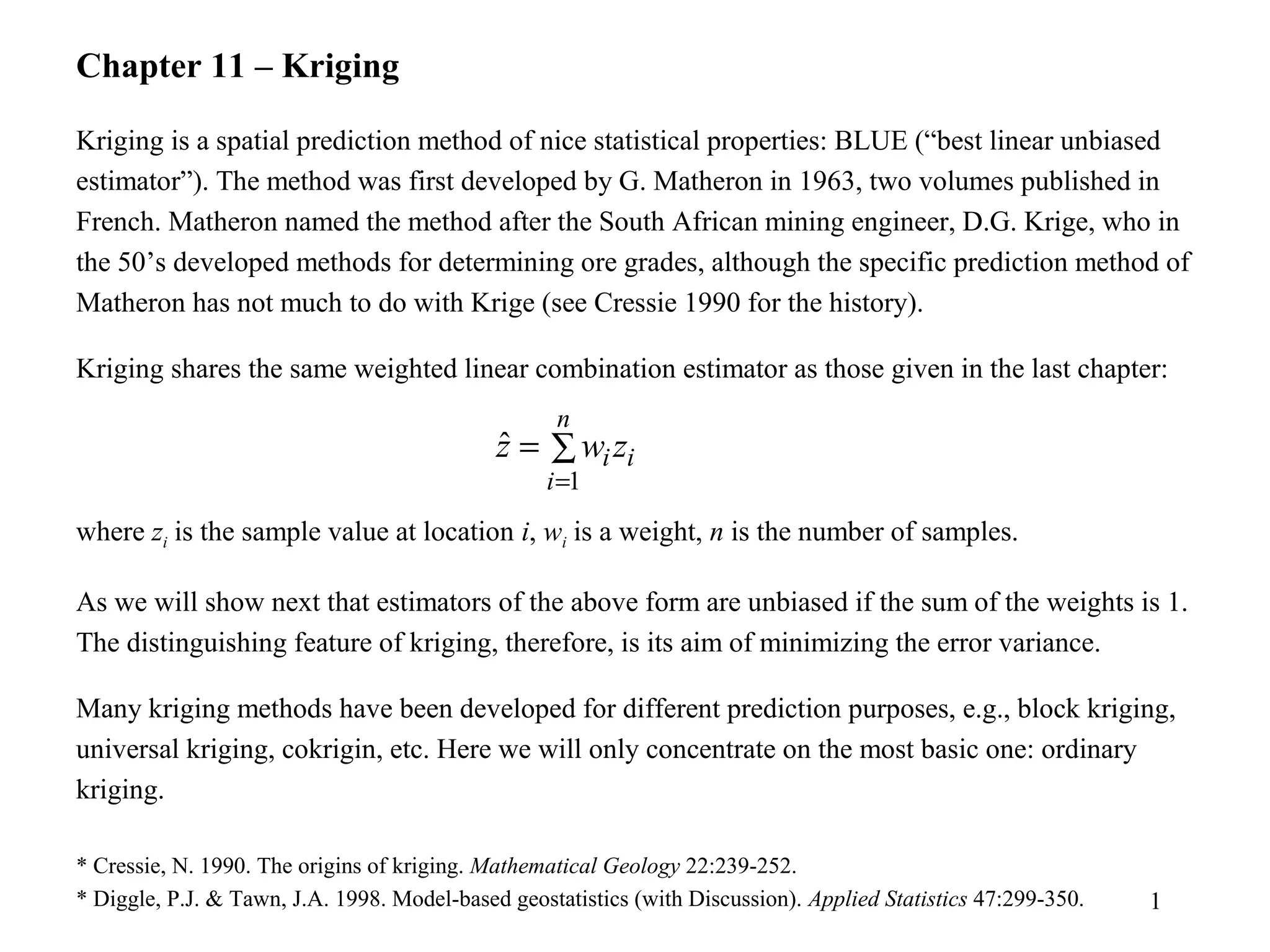

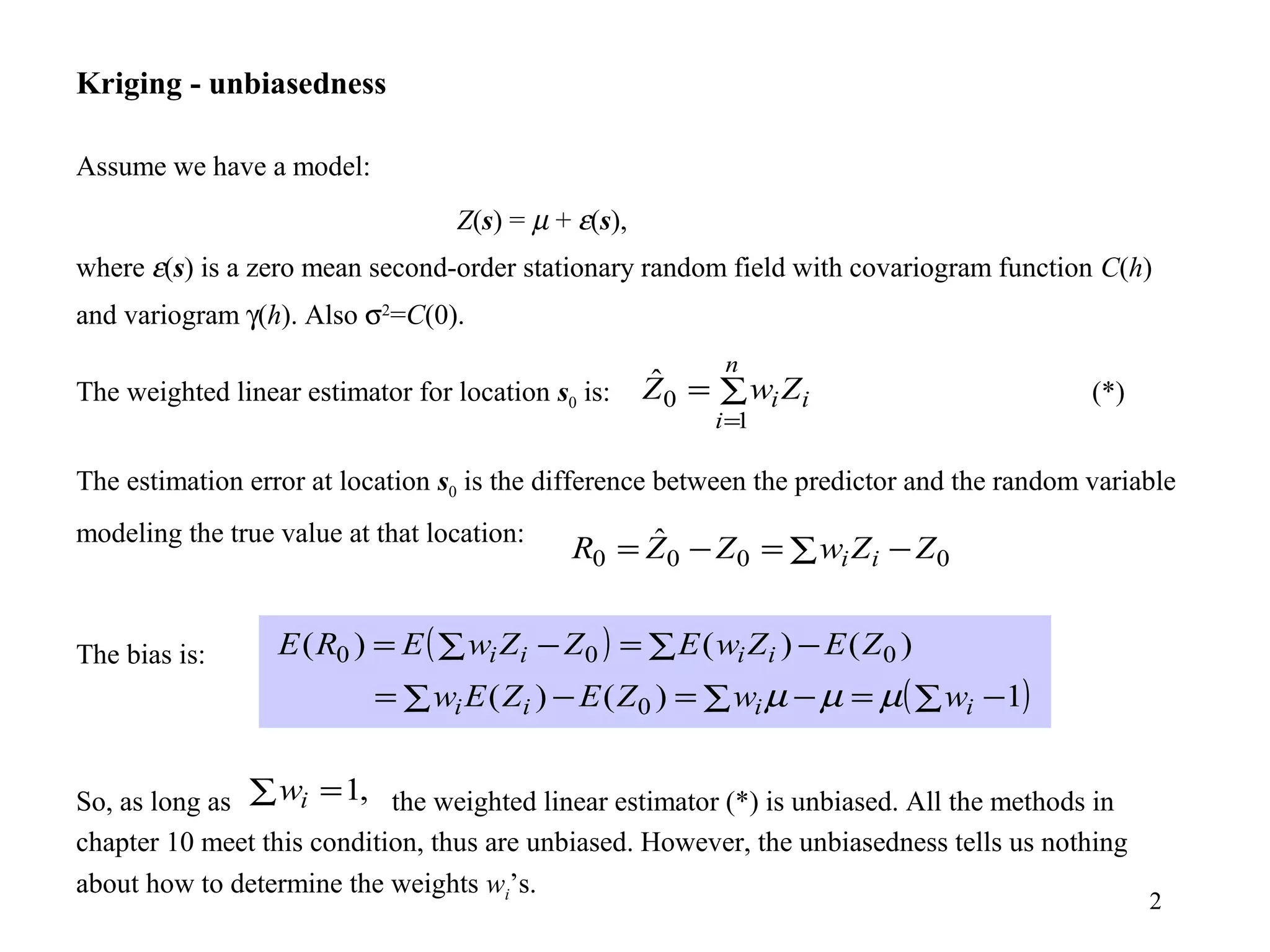

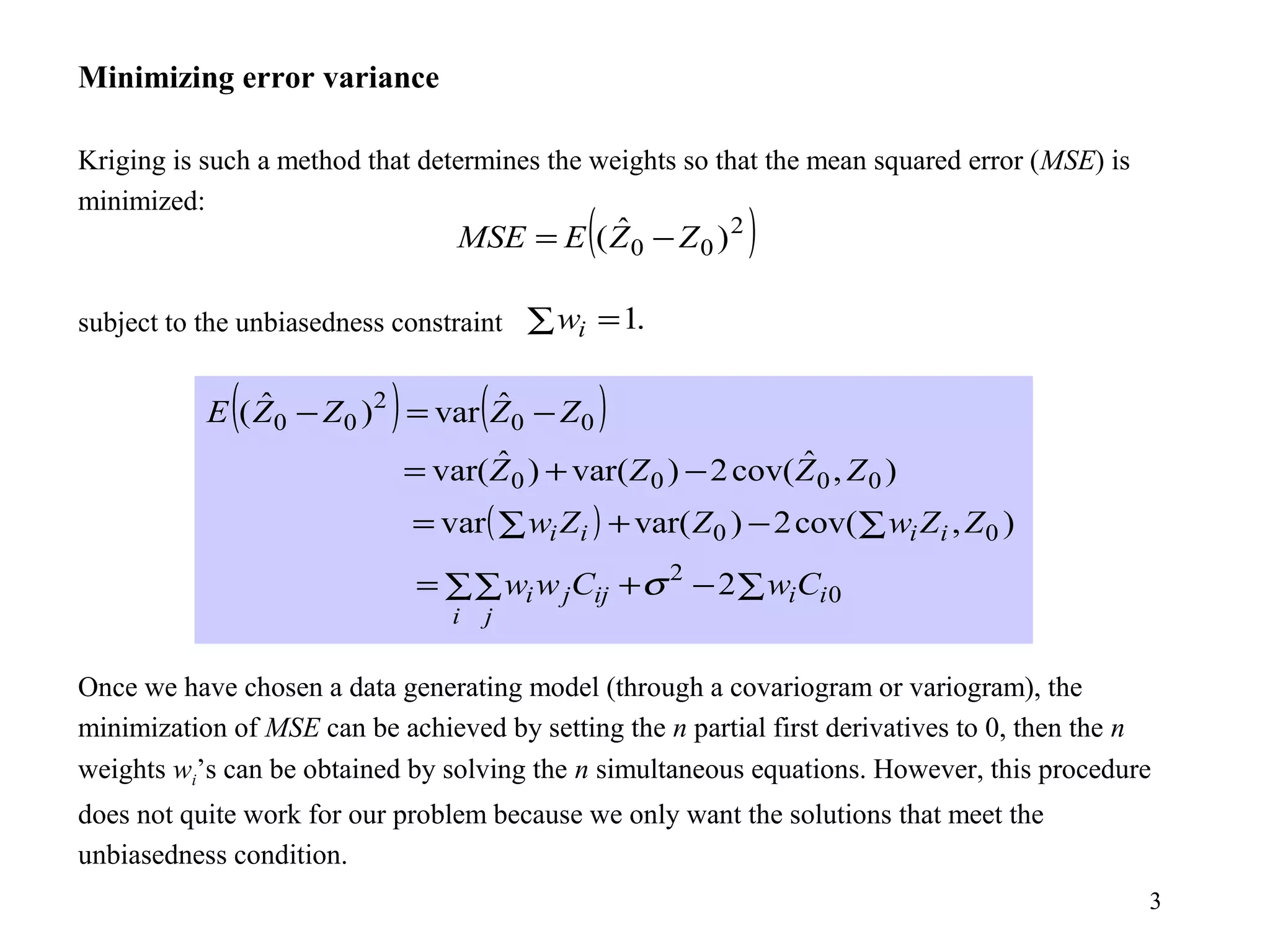

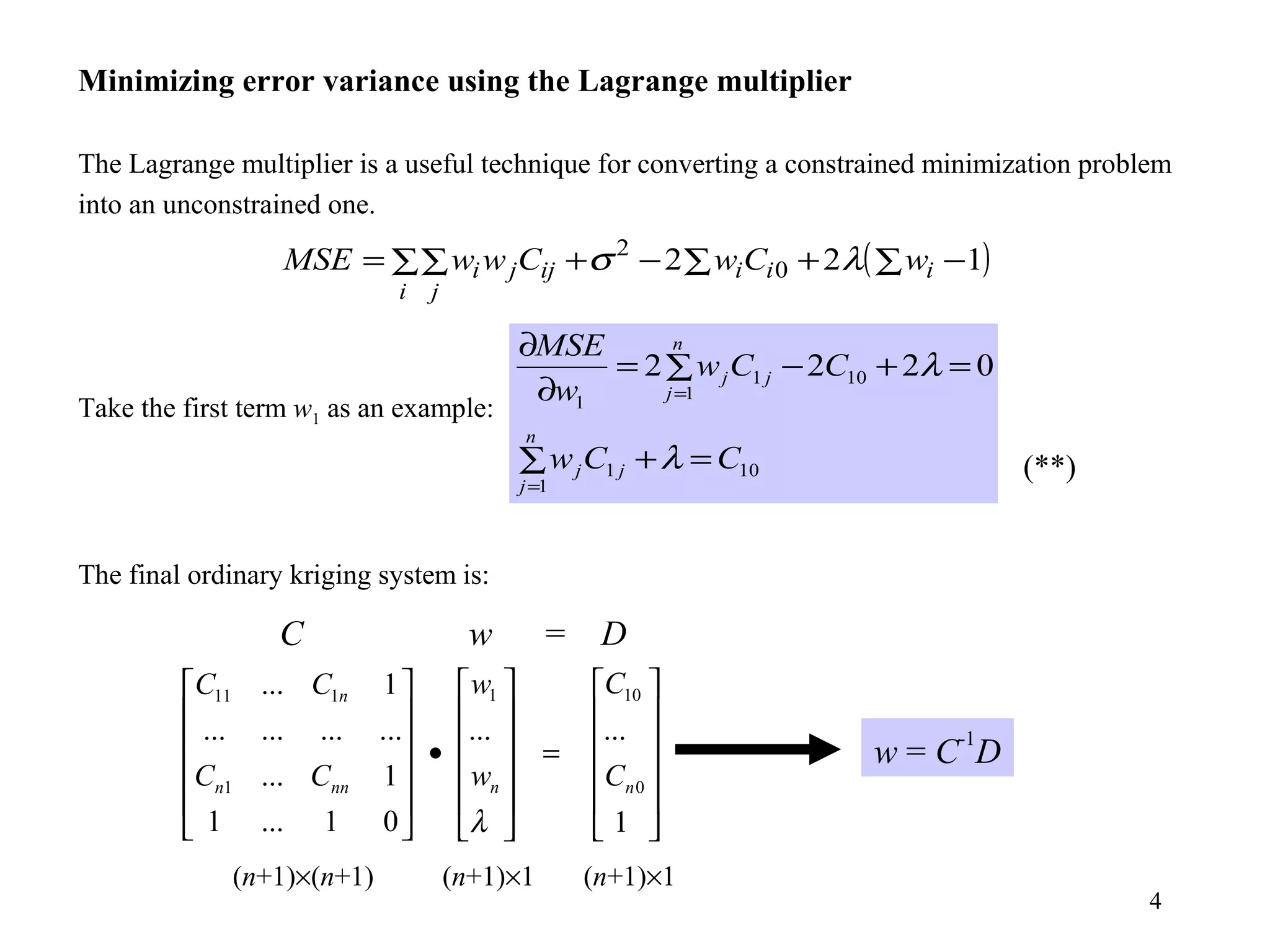

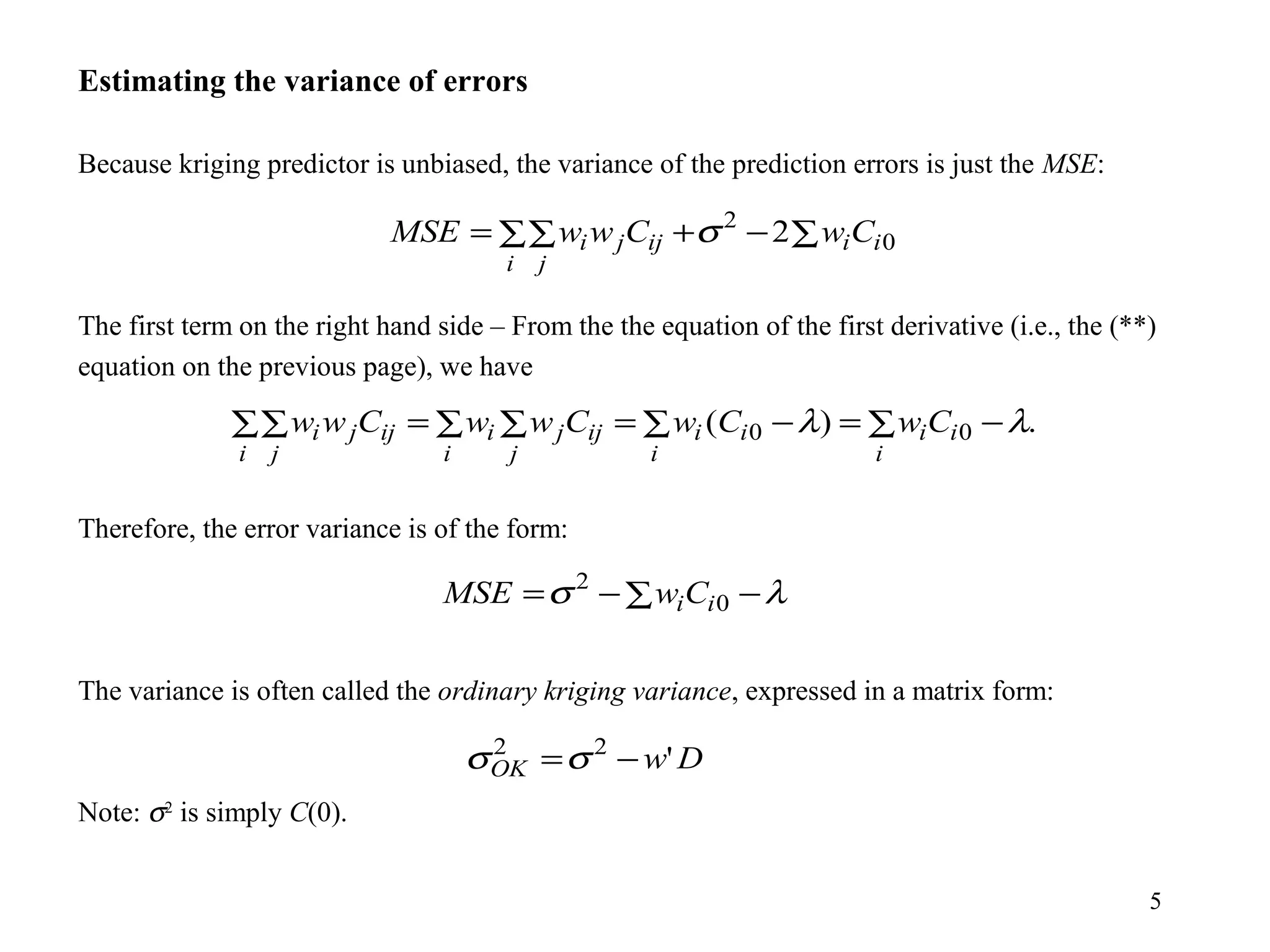

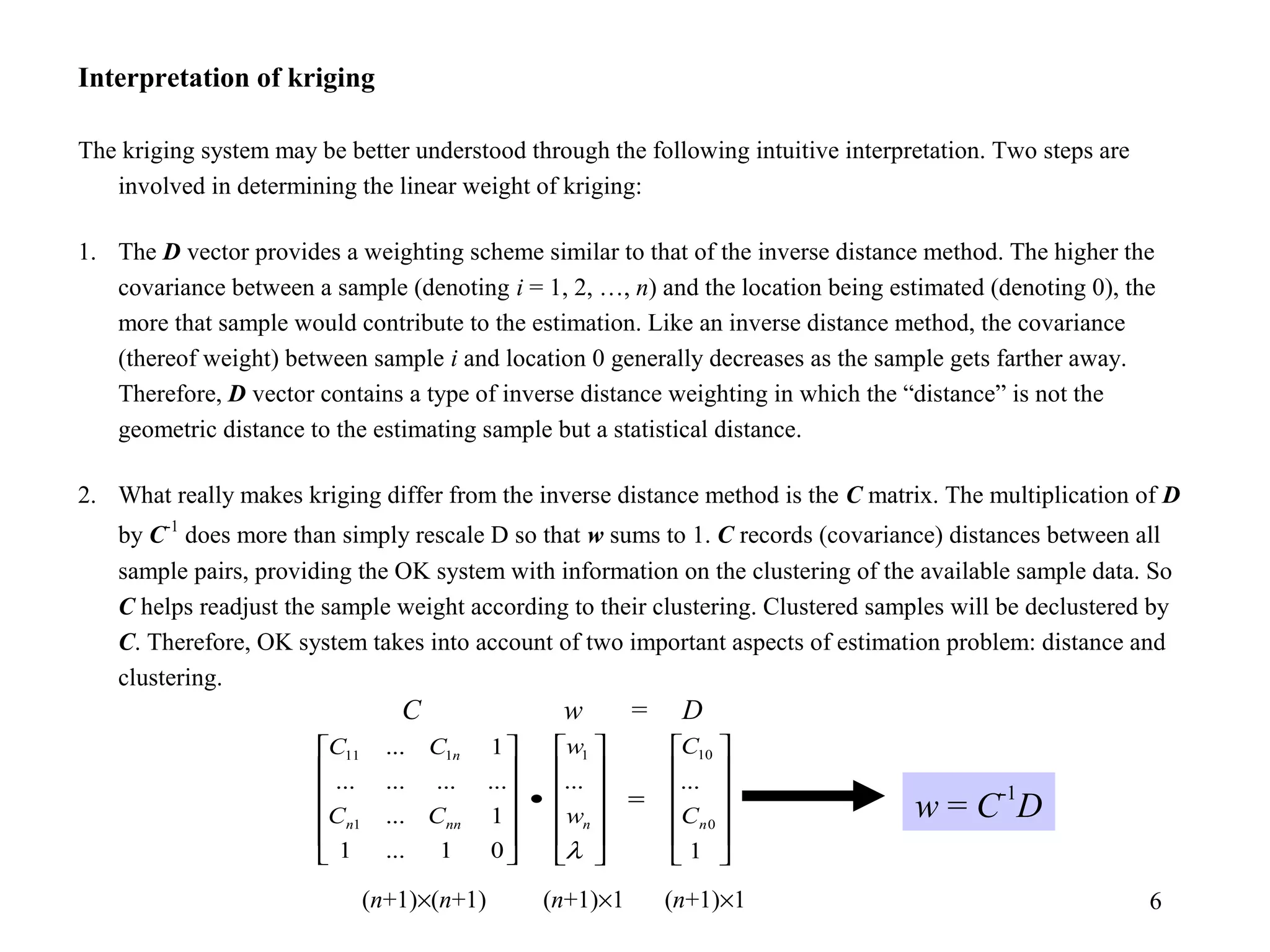

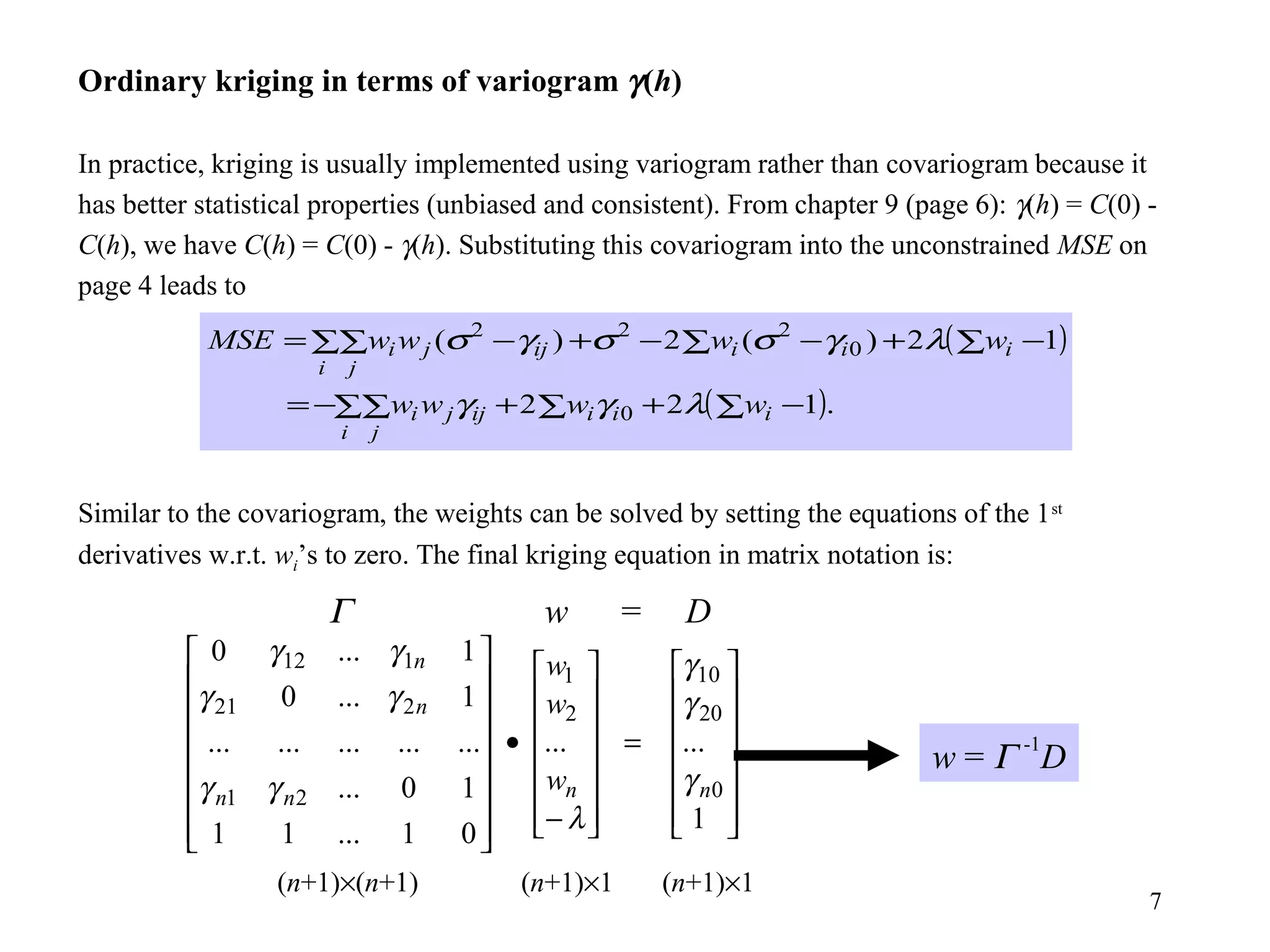

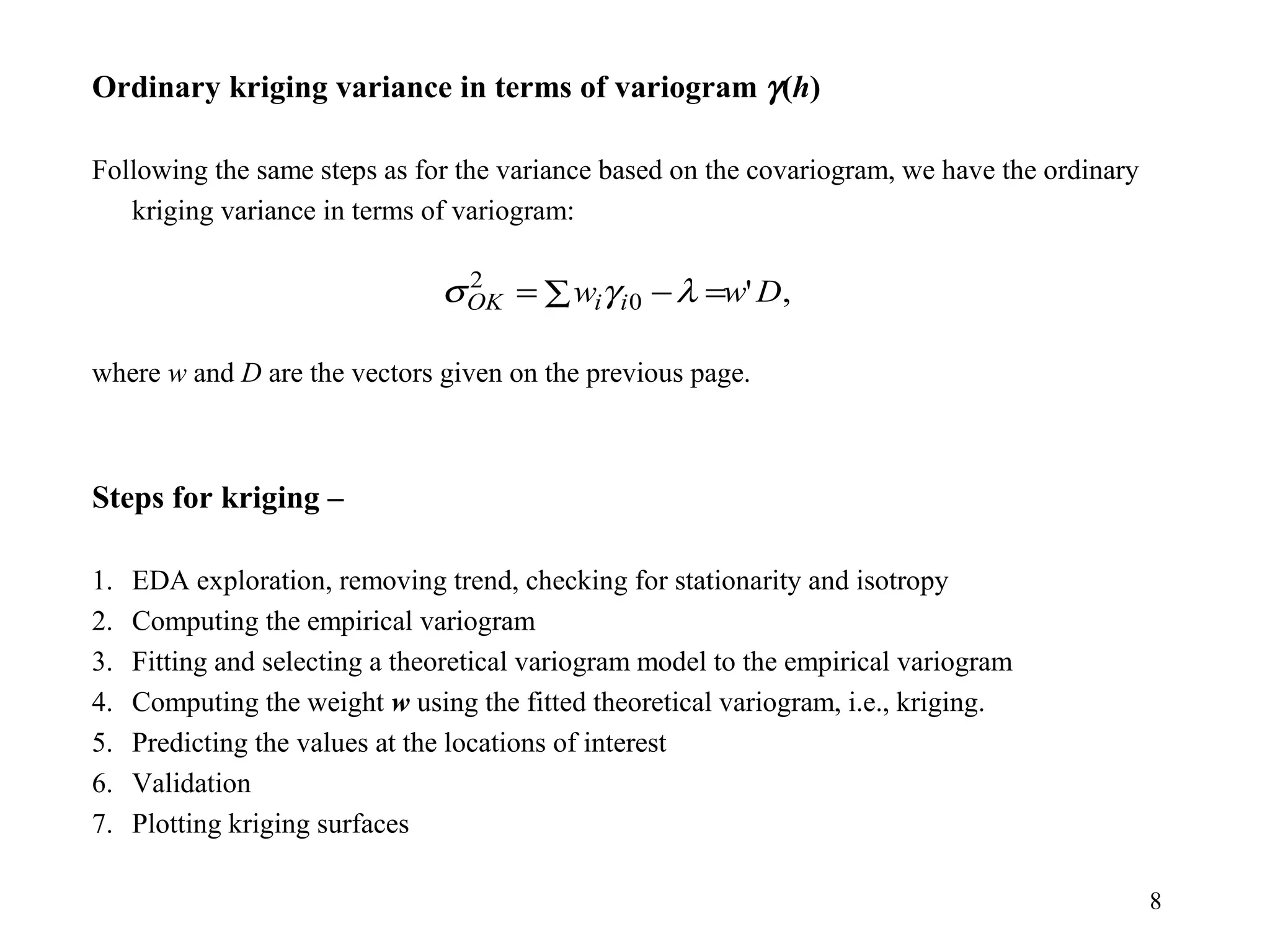

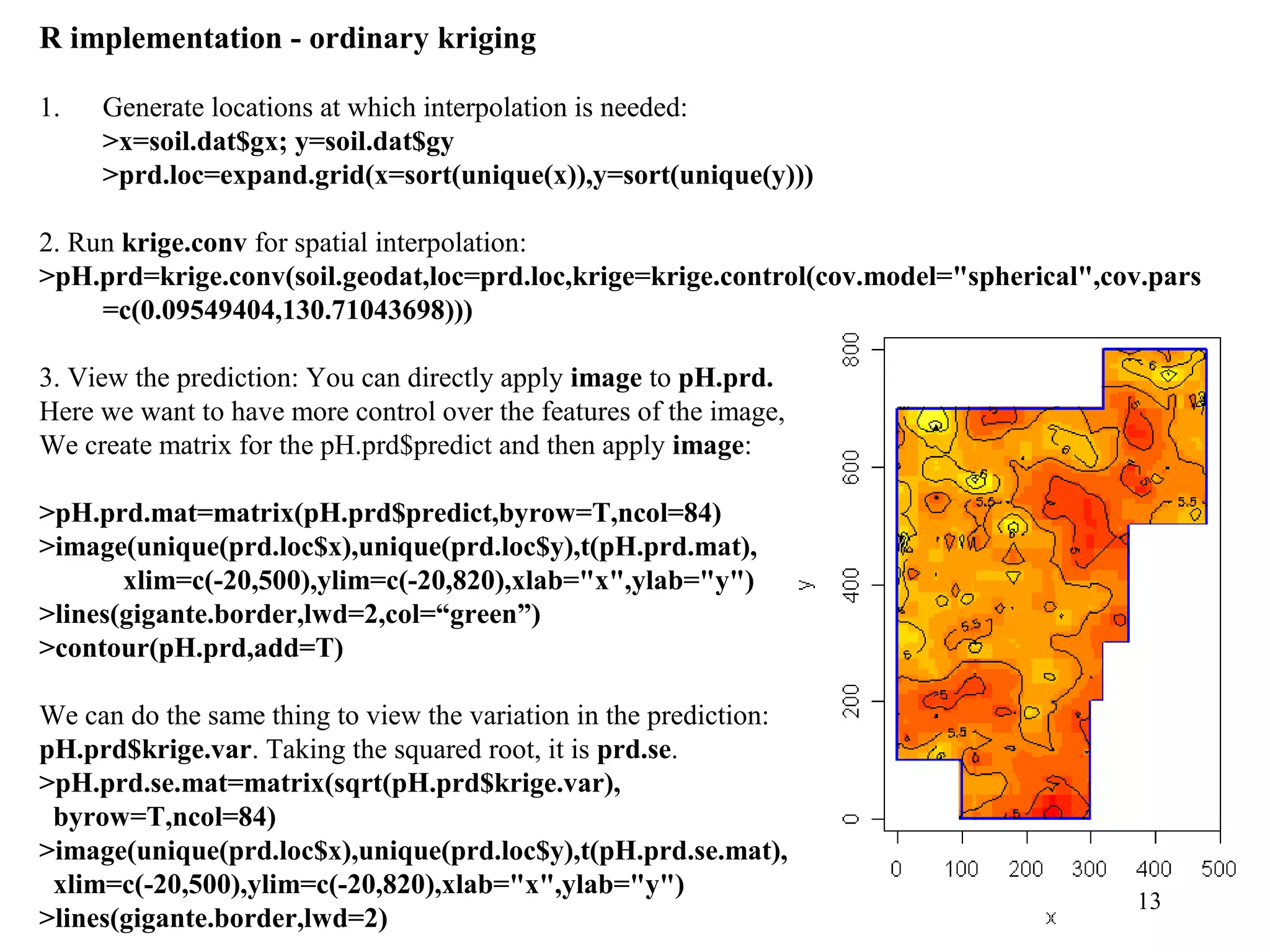

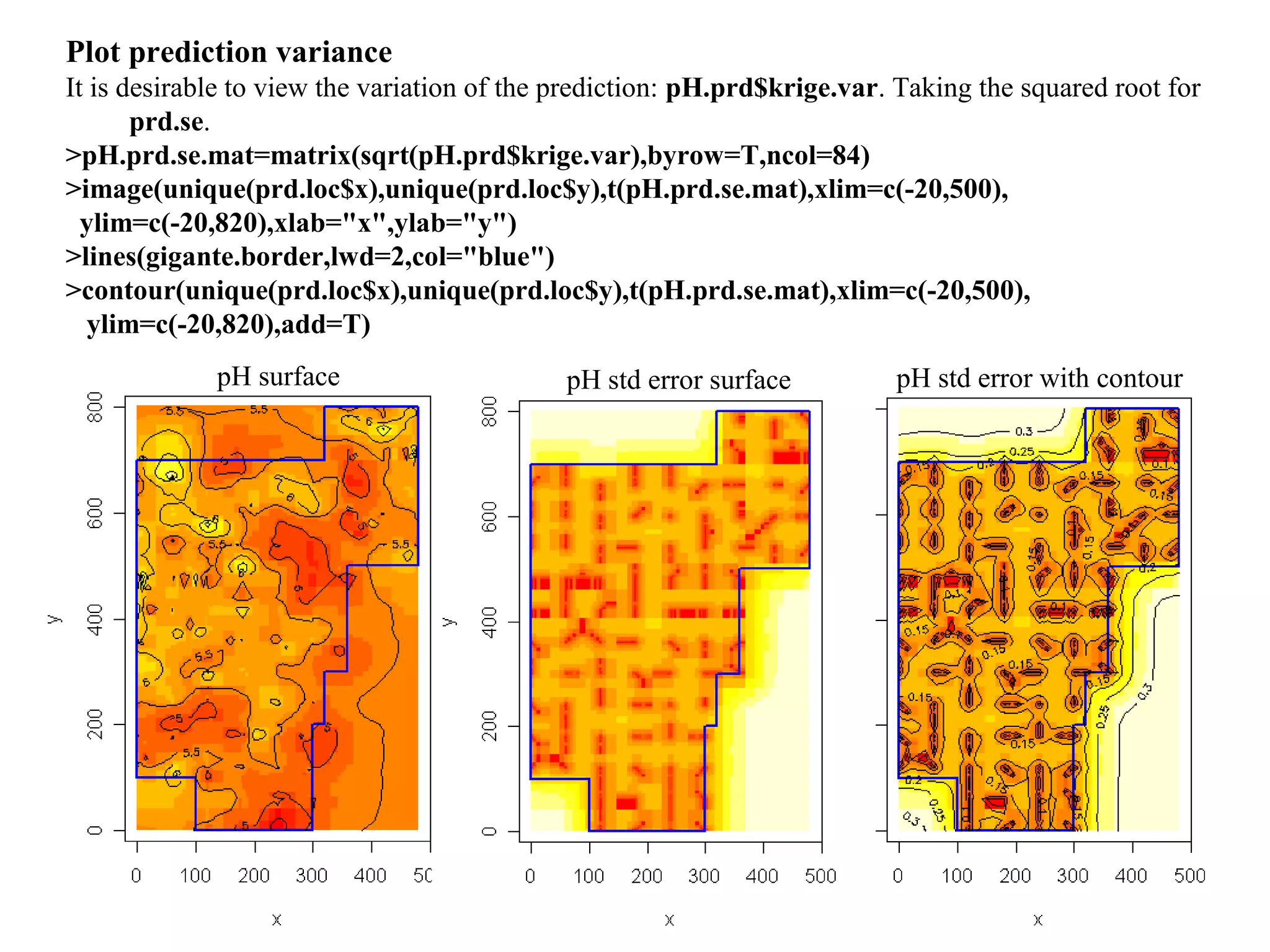

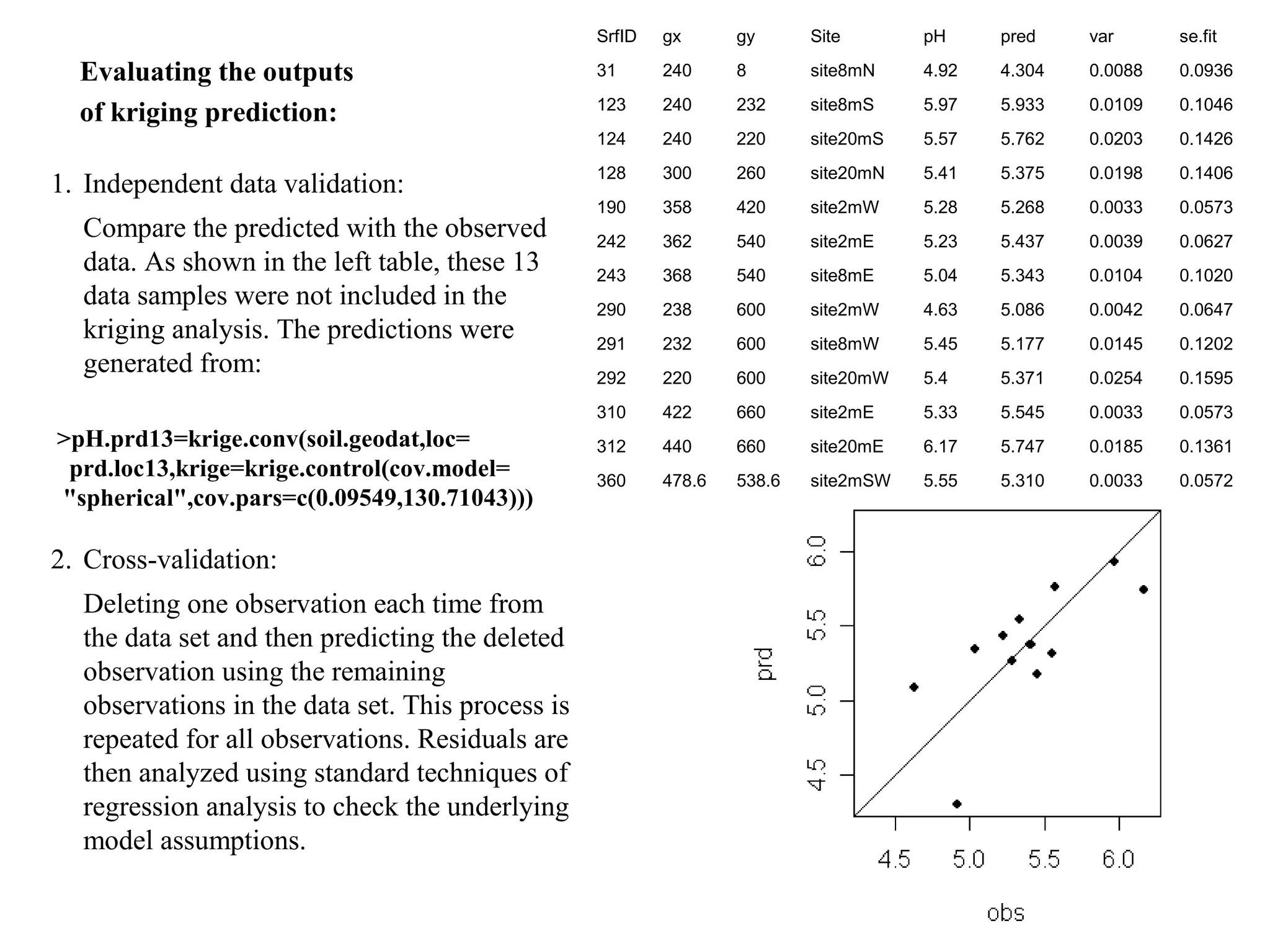

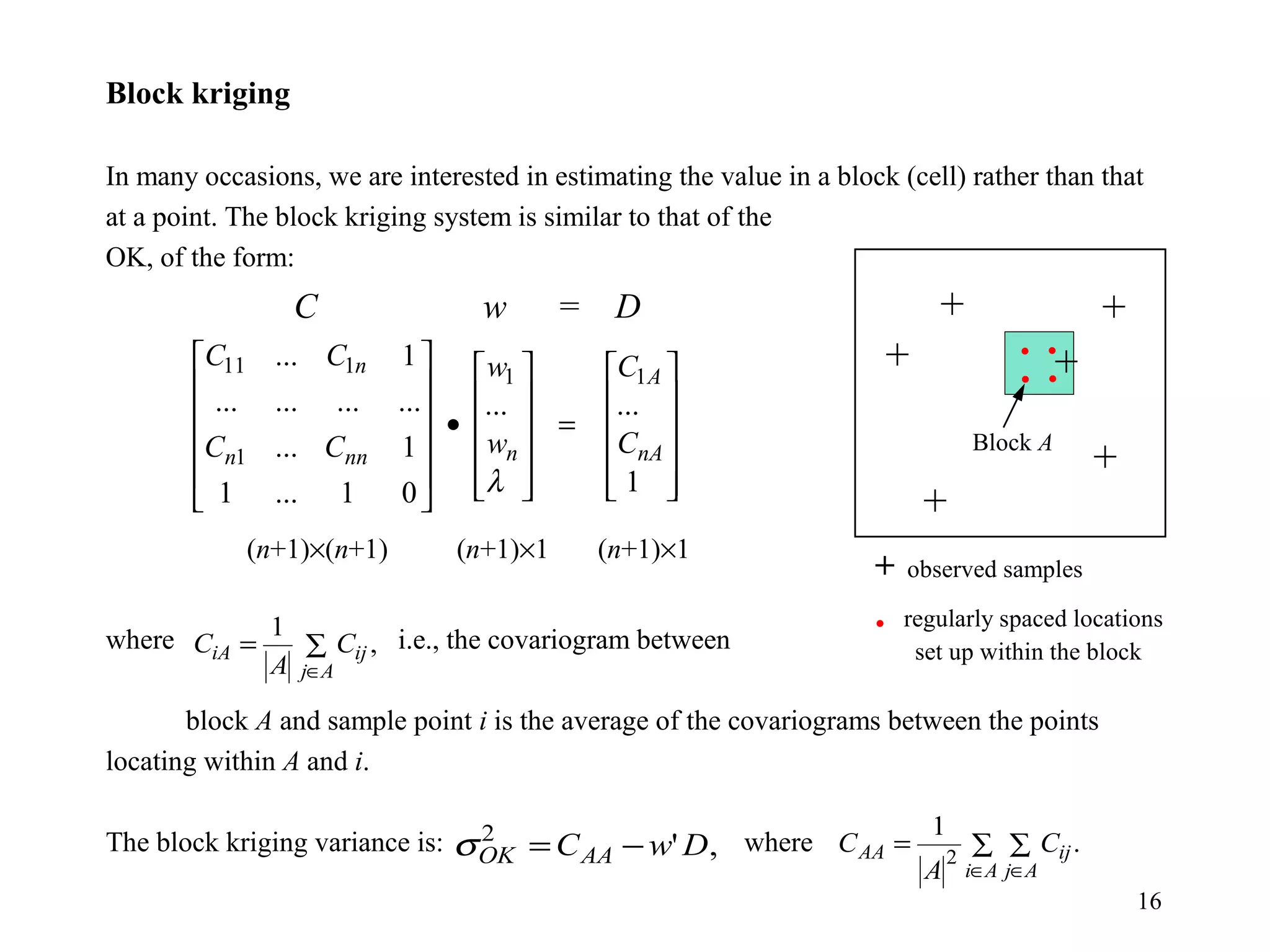

Kriging is a spatial prediction method that provides the "best linear unbiased estimator" (BLUE). It determines weights for a weighted linear combination of sample points that minimizes the prediction error variance. Ordinary kriging focuses on minimizing this error variance based on a variogram model that describes the spatial correlation between sample points. The kriging system is solved to determine the weights, and the predicted values and kriging variance can then be estimated at desired locations.