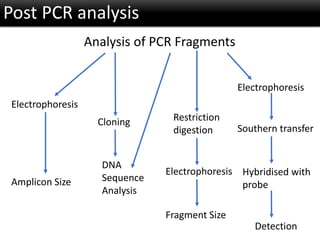

r-DNA technology allows the manipulation of DNA fragments through restriction endonucleases, cloning techniques, and specific probes. Restriction endonucleases cut DNA into fragments, cloning techniques amplify specific sequences, and probes identify sequences of interest. Real-time PCR and restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) are techniques used to analyze DNA fragments.