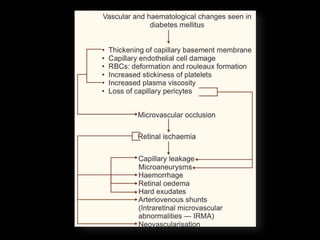

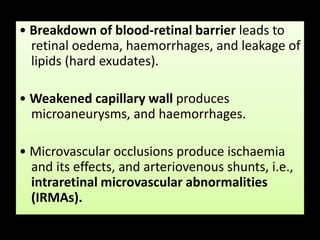

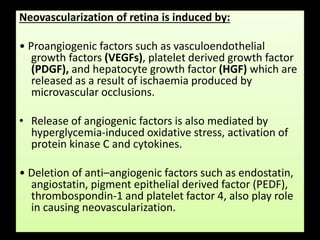

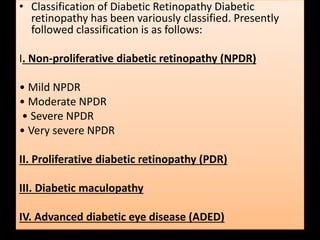

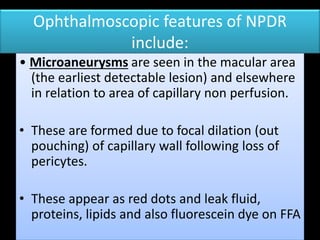

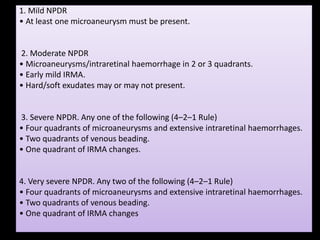

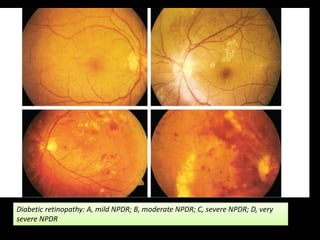

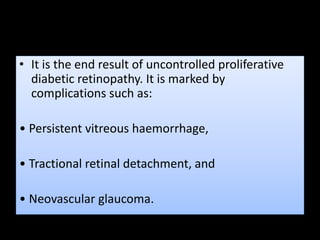

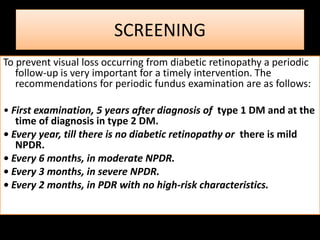

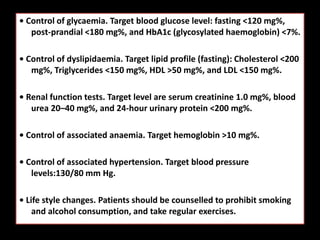

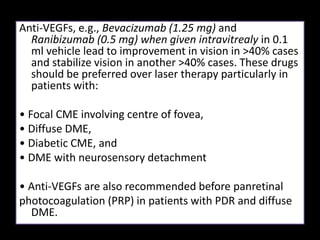

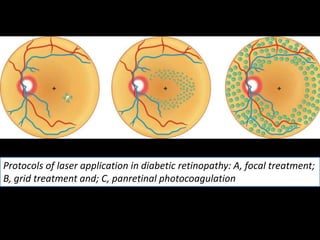

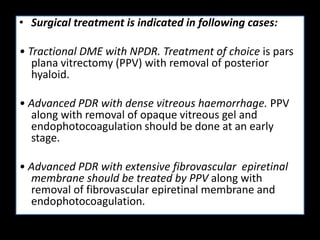

Diabetic retinopathy (DR) is a major cause of blindness linked to diabetes mellitus, with risk factors including the duration of diabetes, age at onset, sex, and metabolic control. The pathology is characterized by microangiopathy leading to retinal damage, and it can be classified into non-proliferative and proliferative stages, each with specific features and treatment approaches. Management includes regular screenings, metabolic control, pharmacotherapy such as anti-VEGF agents, and laser therapies to prevent progression and preserve vision.