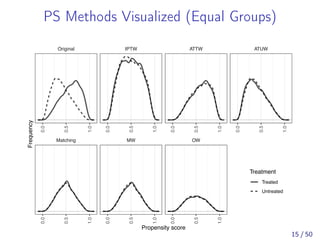

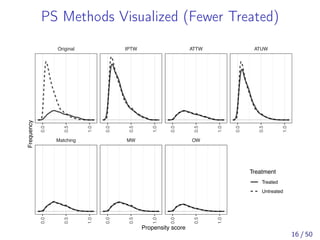

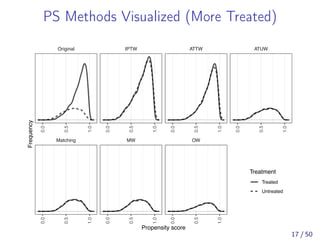

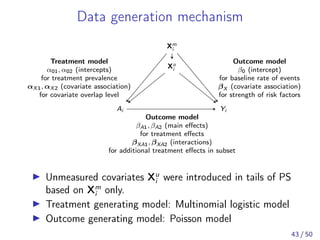

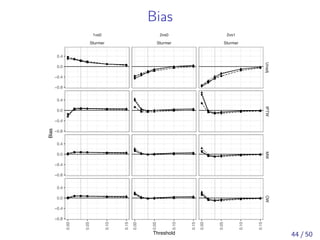

The document discusses the use of propensity score methods in comparative effectiveness research (CER) involving multiple treatment groups, highlighting adjustments for various types of treatments. It covers the challenges and methodologies for designing multi-group CER, including examples and simulations demonstrating the efficiency of methods like matching weights (MW) and their advantages over traditional pairwise matching and inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW). Empirical findings from datasets are also presented to support the effectiveness of different propensity score techniques in balancing covariates across treatment groups.

![Multi-group Comparative Effectiveness

Increasing availability of multiple medications

=⇒ Need for CER involving multiple groups.

Recent observational CER examples in literature:

[Zeng et al., 2019] Analgesics: Tramadol, Naproxen,

Diclofenac, Celecoxib, Etoricoxib, Codeine

[Pawar et al., 2019] Biological Antirheumatics:

Tocilizumab, Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors, Abatacept

[Bergstra et al., 2019] Antirheumatics: Synthetic,

Synthetic + Glucocorticoids, Biological w or w/o

synthetic

[Shah et al., 2018] Anticoagulants: Rivaroxaban,

Dabigatran, Apixaban, Warfarin

6 / 50](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slidesonline-190318233323/85/Propensity-Score-Methods-for-Comparative-Effectiveness-Research-with-Multiple-Treatment-Groups-2-320.jpg)

![Propensity Score Methods and CER

Propensity score (PS) [Rosenbaum and Rubin, 1983]

methods are routinely used in CER comparing two

treatment strategies.

Adjustment [Rosenbaum and Rubin, 1983]

Stratification [Rosenbaum and Rubin, 1984]

Matching [Rosenbaum and Rubin, 1985]

Weighting [Rosenbaum, 1987]

However, when there are more than two treatment

strategies of interest, adaptation is less clear and varies

across fields. [Lopez and Gutman, 2017]

7 / 50](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slidesonline-190318233323/85/Propensity-Score-Methods-for-Comparative-Effectiveness-Research-with-Multiple-Treatment-Groups-3-320.jpg)

![Approaches in Examples

Paper Treatment Approach

[Zeng et al., 2019] Analgesics Pairwise PS, Match

[Pawar et al., 2019] Biologics Pairwise PS, Match

[Bergstra et al., 2019] Antirheumatics Multinom PS, Adjust

[Shah et al., 2018] Anticoagulants Pairwise PS, Adjust

Several options in multi-group CER.

Cohort Construction: Pairwise vs Simultaneous eligibility

PS Estimation: Binary vs Multinomial (logistic) model

PS Methods: Adjustment, Stratification, Matching, or

Weighting

8 / 50](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slidesonline-190318233323/85/Propensity-Score-Methods-for-Comparative-Effectiveness-Research-with-Multiple-Treatment-Groups-4-320.jpg)

![Example of RCT with Multiple Groups

Prospective Randomized Evaluation of Celecoxib

Integrated Safety versus Ibuprofen or Naproxen

(PRECISION) trial [Becker et al., 2009, Nissen et al., 2016]

9 / 50](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slidesonline-190318233323/85/Propensity-Score-Methods-for-Comparative-Effectiveness-Research-with-Multiple-Treatment-Groups-5-320.jpg)

![Notations

Yi : Outcome

Ai : Treatment Strategy

Xi : Vector of Covariates

ei : Propensity Score

where

ei = P[Ai = 1|Xi ]

12 / 50](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slidesonline-190318233323/85/Propensity-Score-Methods-for-Comparative-Effectiveness-Research-with-Multiple-Treatment-Groups-8-320.jpg)

![Balancing Weights

[Li et al., 2018] organized existing PS weighting strategies

as a class of weights (covariate) "balancing weights".

The balancing weight for a given individual is defined as:

h(Xi )

Ai ei + (1 − Ai )(1 − ei )

= h(Xi )IPTWi

where h(·) is a prespecified scalar function of Xi , but not Ai .

Intuition:

Denominator (IPTW) balances groups in covariates

Numerator h(·) manipulates target population (estimand)

13 / 50](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slidesonline-190318233323/85/Propensity-Score-Methods-for-Comparative-Effectiveness-Research-with-Multiple-Treatment-Groups-9-320.jpg)

![PS Weighting with Binary Strategy

IPTWi =

1

Ai ei + (1 − Ai )(1 − ei )

=

⎧

⎪⎪⎨

⎪⎪⎩

1

ei

for Ai = 1

1

1 − ei

for Ai = 0

ATTWi =

ei

Ai ei + (1 − Ai )(1 − ei )

=

⎧

⎨

⎩

1 for Ai = 1

ei

1 − ei

for Ai = 0

ATUWi =

1 − ei

Ai ei + (1 − Ai )(1 − ei )

=

⎧

⎨

⎩

1 − ei

ei

for Ai = 1

1 for Ai = 0

MWi =

min {ei , 1 − ei }

Ai ei + (1 − Ai )(1 − ei )

=

ATTWi for ei ≤ 0.5

ATUWi for ei > 0.5

OWi =

ei (1 − ei )

Ai ei + (1 − Ai )(1 − ei )

=

1 − ei for Ai = 1

ei for Ai = 0

[Rosenbaum, 1987, Robins et al., 2000, Sato and Matsuyama, 2003, Li and Greene, 2013,

Li et al., 2018]

14 / 50](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slidesonline-190318233323/85/Propensity-Score-Methods-for-Comparative-Effectiveness-Research-with-Multiple-Treatment-Groups-10-320.jpg)

![Asymptotic Equivalence of MW and 1:1 PSM

[Li and Greene, 2013] proved the asymptotic equivalence

of the MW estimand and 1:1 PS matching estimand

under:

Finite PS space (no growth with n)

Positivity (i.e., perfect overlap)

1:1 exact PS matching

18 / 50](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slidesonline-190318233323/85/Propensity-Score-Methods-for-Comparative-Effectiveness-Research-with-Multiple-Treatment-Groups-14-320.jpg)

![Estimands

Using balancing weights [Li et al., 2018] various

population can be targeted for inference of the (marginal)

treatment effect.

IPTW targets average treatment effect (ATE).

We can weights specifically for the average treatment

effect on the treated (ATT) or untreated (ATU)

1:1 PSM and MW target the treatment effect in a

feasible subset of the sample.

[Samuels and Greevy, 2018] named this estimand

"average treatment effect on the evenly matchable units"

(ATM).

OW similarly targets a feasible subset.

19 / 50](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slidesonline-190318233323/85/Propensity-Score-Methods-for-Comparative-Effectiveness-Research-with-Multiple-Treatment-Groups-15-320.jpg)

![Generalized PS

Conditional probability of receiving a particular level of

the treatment given the pre-treatment variables:

[Imbens, 2000]

Ai ∈ {0, 1, ..., J}

eji = P[Ai = j|Xi ]

Subject to

J

j=0

eji = 1

Each individual has a PS vector ei = (e0i , e1i , . . . , eJi )T

.

21 / 50](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slidesonline-190318233323/85/Propensity-Score-Methods-for-Comparative-Effectiveness-Research-with-Multiple-Treatment-Groups-17-320.jpg)

![Generalized Balancing Weights

[Li and Li, 2018] extended the balancing weights

framework using the generalized PS.

Using our notation,

h(Xi )

J

j=0

eji I(Ai = j)

= h(Xi )IPTWi

where h(·) is a prespecified scalar function of Xi , but not Ai .

Intuition:

Denominator (IPTW) balances groups in covariates

Numerator h(·) manipulates target population (estimand)

22 / 50](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slidesonline-190318233323/85/Propensity-Score-Methods-for-Comparative-Effectiveness-Research-with-Multiple-Treatment-Groups-18-320.jpg)

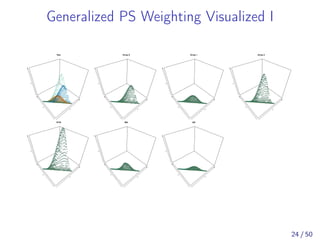

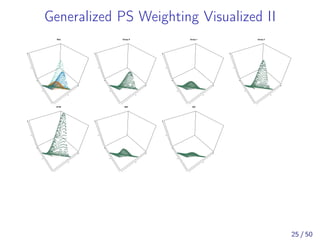

![Generalized PS Weighting

IPTWi =

1

J

j=0

eji I(Ai = j)

=

1

eAi i

> 1 for all Ai

AT(k)Wi =

eji

J

j=0

eki I(Ai = j)

=

⎧

⎨

⎩

1 for Ai = k

eki

eAi i

for Ai ̸= k

MWi =

minj {eji }

J

j=0

eji I(Ai = j)

=

⎧

⎨

⎩

1 for Ai = argminj {eji }

minj {eji }

eAi i

< 1 otherwise

OWi =

J

j=0

1

eji

−1

J

j=0

eji I(Ai = j)

=

⎧

⎨

⎩

1

eAi i

1

J

l=0

1

eli

< 1 for all Ai = 1

[Yoshida et al., 2017, Li and Li, 2018]

23 / 50](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slidesonline-190318233323/85/Propensity-Score-Methods-for-Comparative-Effectiveness-Research-with-Multiple-Treatment-Groups-19-320.jpg)

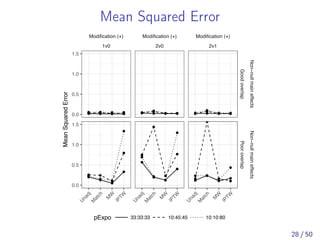

![Simulation Study

[Yoshida et al., 2017] examined 3-group MW in

comparison to 3-group IPTW and 1:1:1 simultaneous

three-way matching [Rassen et al., 2013].

OW was not included.

27 / 50](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slidesonline-190318233323/85/Propensity-Score-Methods-for-Comparative-Effectiveness-Research-with-Multiple-Treatment-Groups-23-320.jpg)

![Estimands

Modification (+)

1v0

Modification (+)

2v0

Modification (+)

2v1

Goodoverlap

Non−nullmaineffects

Pooroverlap

Non−nullmaineffects

U

nadj

M

atch

M

W

IPTW

U

nadj

M

atch

M

W

IPTW

U

nadj

M

atch

M

W

IPTW

0.40

0.50

0.75

1.00

0.40

0.50

0.75

1.00

TrueRiskRatio

pExpo 33:33:33 10:45:45 10:10:80

Estimand calculation was based on the counterfactual method described in [Austin, 2013] 29 / 50](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slidesonline-190318233323/85/Propensity-Score-Methods-for-Comparative-Effectiveness-Research-with-Multiple-Treatment-Groups-25-320.jpg)

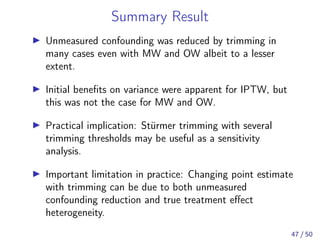

![Simulation: Summary results

Comparing MW to three-way matching and IPTW, we found:

Similar estimands for MW and matching, but not IPTW

Best covariate balance

Similarly small bias compared to matching

Smaller MSE compared to matching in all scenarios

More robust to rare events, unequally sized groups, and

poor covariate overlap

The full results are available in [Yoshida et al., 2017]

30 / 50](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slidesonline-190318233323/85/Propensity-Score-Methods-for-Comparative-Effectiveness-Research-with-Multiple-Treatment-Groups-26-320.jpg)

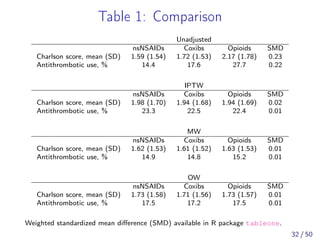

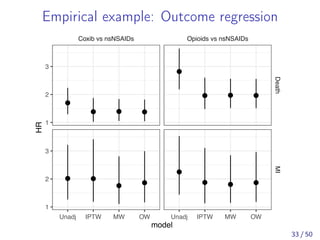

![Empirical example

Medicare Beneficiary dataset from PA and NJ

(1999-2005) [Solomon et al., 2010]

Unadjusted

nsNSAIDs Coxibs Opioids SMD

n 4874 6172 12601

Charlson score, mean (SD) 1.59 (1.54) 1.72 (1.53) 2.17 (1.78) 0.23

Antithrombotic use, % 14.4 17.6 27.7 0.22

No. prescription drugs, mean (SD) 8.28 (4.69) 8.55 (4.76) 9.76 (5.38) 0.20

No. days in hospital, mean (SD) 1.85 (6.90) 2.19 (6.86) 4.18 (9.46) 0.19

White race, % 84.6 88 92.4 0.16

Fracture, % 6.5 7.2 13.7 0.16

Loop diuretic use, % 21.3 25.8 31.3 0.15

Age, mean (SD) 79.67 (7.03) 80.87 (6.99) 81.15 (7.17) 0.14

No. physician visits, mean (SD) 8.72 (6.32) 8.80 (5.99) 10.08 (7.14) 0.14

Myocardial infarction, % 5.2 5.7 9.6 0.11

Stroke, % 15.2 16.1 21.5 0.11

31 / 50](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slidesonline-190318233323/85/Propensity-Score-Methods-for-Comparative-Effectiveness-Research-with-Multiple-Treatment-Groups-27-320.jpg)

![Conclusion

MW has been suggested as a more efficient alternative to

1:1 pairwise matching. [Li and Greene, 2013]

In a simulation study with three treatment groups, MW

demonstrated similar bias, but smaller MSE compared to

1:1:1 three-way matching. [Rassen et al., 2013]

Efficiency gain compared to 1:1:1 three-way matching was

more noticeable in scenarios in which the outcome events

were rare, treatment groups were unequally sized, or

covariate overlap was poor.

Compared to IPTW, MW was more stable in the poor

covariate overlap setting.

Confirming the type of patients that MW is making

inference for is important in practice.

34 / 50](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slidesonline-190318233323/85/Propensity-Score-Methods-for-Comparative-Effectiveness-Research-with-Multiple-Treatment-Groups-30-320.jpg)

![PS Trimming

Propensity score trimming has been suggested by several

authors.

To increase efficiency [Crump et al., 2009]

To reduce unmeasured confounding

[Stürmer et al., 2010]

To guide study design [Walker et al., 2013]

[Yoshida et al., 2019] examined multi-group extension of

all three.

Here we focus on the extension of [Stürmer et al., 2010].

36 / 50](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slidesonline-190318233323/85/Propensity-Score-Methods-for-Comparative-Effectiveness-Research-with-Multiple-Treatment-Groups-32-320.jpg)

![Motivation for Stürmer’s PS Trimming

[Stürmer et al., 2010] was concerned with very

heterogeneous treatment effects in the tails of PS

distribution.

[Kurth et al., 2006] tissue plasminogen activator (t-PA)

use vs no t-PA use in stroke patients. Outcome

in-hospital death. Very high mortality in t-PA users with

lowest probabilities for t-PA.

[Lunt et al., 2009] tumor necrosis factor inhibitor (TNFi)

initiation vs non-TNFi treatment in rheumatoid arthritis

patients. Outcome death. Higher mortality among

non-TNFi users with highest probabilities for TNFi

initiation.

[Stürmer et al., 2010] hypothesized that there may be

higher prevalence of unmeasured confounders that

preferentially introduce more confounding in the tails.

37 / 50](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slidesonline-190318233323/85/Propensity-Score-Methods-for-Comparative-Effectiveness-Research-with-Multiple-Treatment-Groups-33-320.jpg)

![Definition of Stürmer’s PS Trimming

[Stürmer et al., 2010] proposed the asymmetric PS

trimming to remedy this.

Their simulation study confirmed its benefit in bias

reduction if indeed the tails of PS contained higher

prevalence of unmeasured confounders.

38 / 50](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slidesonline-190318233323/85/Propensity-Score-Methods-for-Comparative-Effectiveness-Research-with-Multiple-Treatment-Groups-34-320.jpg)

![Question

[Stürmer et al., 2010] demonstrated benefits of PS

trimming in reducing unmeasured confounding in the

presence of unmeasured confounders that were more

prevalent in the tails of the PS distribution.

How can we conceptualize this issue in the general

setting?

How can we extend their method?

39 / 50](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slidesonline-190318233323/85/Propensity-Score-Methods-for-Comparative-Effectiveness-Research-with-Multiple-Treatment-Groups-35-320.jpg)

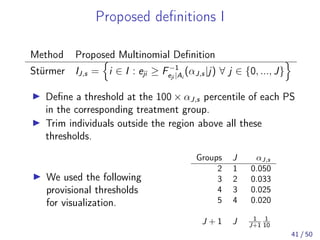

![Original Two-Group Definition

Method Existing Binary Definition

Stürmer Is = i ∈ I : ei ∈ F−1

ei |Ai

(0.05|1), F−1

ei |Ai

(0.95|0)

Define the lower threshold using the treated PS

distribution.

Define the upper threshold

Notation Explanation

i ∈ {1, ..., n} index for an individual

I = {1, ..., n} index set for entire sample

Ai ∈ {0, 1} treatment variable

ei = P[Ai = 1|Xi ] propensity score

p = P[Ai = 1] treatment prevalence

F−1

ei |Ai

(x|a) treatment-specific quantile of ei

40 / 50](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slidesonline-190318233323/85/Propensity-Score-Methods-for-Comparative-Effectiveness-Research-with-Multiple-Treatment-Groups-36-320.jpg)

![Bibliography I

[Austin, 2013] Austin, P. C. (2013).

The performance of different propensity score methods for estimating marginal hazard ratios.

Stat Med, 32(16):2837–2849.

[Becker et al., 2009] Becker, M. C., Wang, T. H., Wisniewski, L., Wolski, K., Libby, P., Lüscher, T. F.,

Borer, J. S., Mascette, A. M., Husni, M. E., Solomon, D. H., Graham, D. Y., Yeomans, N. D.,

Krum, H., Ruschitzka, F., Lincoff, A. M., Nissen, S. E., and PRECISION Investigators (2009).

Rationale, design, and governance of Prospective Randomized Evaluation of Celecoxib Integrated

Safety versus Ibuprofen Or Naproxen (PRECISION), a cardiovascular end point trial of nonsteroidal

antiinflammatory agents in patients with arthritis.

Am. Heart J., 157(4):606–612.

[Bergstra et al., 2019] Bergstra, S. A., Winchow, L.-L., Murphy, E., Chopra, A., Salomon-Escoto, K.,

Fonseca, J. a. E., Allaart, C. F., and Landewé, R. B. M. (2019).

How to treat patients with rheumatoid arthritis when methotrexate has failed? The use of a multiple

propensity score to adjust for confounding by indication in observational studies.

Ann. Rheum. Dis., 78(1):25–30.

[Crump et al., 2009] Crump, R. K., Hotz, V. J., Imbens, G. W., and Mitnik, O. A. (2009).

Dealing with limited overlap in estimation of average treatment effects.

Biometrika, 96(1):187–199.

[Imbens, 2000] Imbens, G. W. (2000).

The role of the propensity score in estimating dose-response functions.

Biometrika, 87(3):706–710.

3 / 7](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slidesonline-190318233323/85/Propensity-Score-Methods-for-Comparative-Effectiveness-Research-with-Multiple-Treatment-Groups-47-320.jpg)

![Bibliography II

[Kurth et al., 2006] Kurth, T., Walker, A. M., Glynn, R. J., Chan, K. A., Gaziano, J. M., Berger, K.,

and Robins, J. M. (2006).

Results of multivariable logistic regression, propensity matching, propensity adjustment, and

propensity-based weighting under conditions of nonuniform effect.

Am. J. Epidemiol., 163(3):262–270.

[Li and Li, 2018] Li, F. and Li, F. (2018).

Propensity Score Weighting for Causal Inference with Multi-valued Treatments.

arXiv:1808.05339 [stat].

[Li et al., 2018] Li, F., Morgan, K. L., and Zaslavsky, A. M. (2018).

Balancing Covariates via Propensity Score Weighting.

Journal of the American Statistical Association, 113(521):390–400.

[Li and Greene, 2013] Li, L. and Greene, T. (2013).

A weighting analogue to pair matching in propensity score analysis.

Int J Biostat, 9(2):215–234.

[Lopez and Gutman, 2017] Lopez, M. J. and Gutman, R. (2017).

Estimation of Causal Effects with Multiple Treatments: A Review and New Ideas.

Statist. Sci., 32(3):432–454.

[Lunt et al., 2009] Lunt, M., Solomon, D., Rothman, K., Glynn, R., Hyrich, K., Symmons, D. P. M.,

Stürmer, T., British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register, and British Society for

Rheumatology Biologics Register Control Centre Consortium (2009).

Different methods of balancing covariates leading to different effect estimates in the presence of

effect modification.

Am. J. Epidemiol., 169(7):909–917.

4 / 7](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slidesonline-190318233323/85/Propensity-Score-Methods-for-Comparative-Effectiveness-Research-with-Multiple-Treatment-Groups-48-320.jpg)

![Bibliography III

[Nissen et al., 2016] Nissen, S. E., Yeomans, N. D., Solomon, D. H., Lüscher, T. F., Libby, P., Husni,

M. E., Graham, D. Y., Borer, J. S., Wisniewski, L. M., Wolski, K. E., Wang, Q., Menon, V.,

Ruschitzka, F., Gaffney, M., Beckerman, B., Berger, M. F., Bao, W., Lincoff, A. M., and

PRECISION Trial Investigators (2016).

Cardiovascular Safety of Celecoxib, Naproxen, or Ibuprofen for Arthritis.

N. Engl. J. Med., 375(26):2519–2529.

[Pawar et al., 2019] Pawar, A., Desai, R. J., Solomon, D. H., Santiago Ortiz, A. J., Gale, S., Bao, M.,

Sarsour, K., Schneeweiss, S., and Kim, S. C. (2019).

Risk of serious infections in tocilizumab versus other biologic drugs in patients with rheumatoid

arthritis: A multidatabase cohort study.

Ann. Rheum. Dis.

[Rassen et al., 2013] Rassen, J. A., Shelat, A. A., Franklin, J. M., Glynn, R. J., Solomon, D. H., and

Schneeweiss, S. (2013).

Matching by propensity score in cohort studies with three treatment groups.

Epidemiology, 24(3):401–409.

[Robins et al., 2000] Robins, J. M., Hernán, M. A., and Brumback, B. (2000).

Marginal structural models and causal inference in epidemiology.

Epidemiology, 11(5):550–560.

[Rosenbaum, 1987] Rosenbaum, P. R. (1987).

Model-Based Direct Adjustment.

Journal of the American Statistical Association, 82(398):387–394.

[Rosenbaum and Rubin, 1983] Rosenbaum, P. R. and Rubin, D. B. (1983).

The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects.

Biometrika, 70(1):41–55.

5 / 7](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slidesonline-190318233323/85/Propensity-Score-Methods-for-Comparative-Effectiveness-Research-with-Multiple-Treatment-Groups-49-320.jpg)

![Bibliography IV

[Rosenbaum and Rubin, 1984] Rosenbaum, P. R. and Rubin, D. B. (1984).

Reducing Bias in Observational Studies Using Subclassification on the Propensity Score.

J Am Stat Assoc, 79(387):516.

[Rosenbaum and Rubin, 1985] Rosenbaum, P. R. and Rubin, D. B. (1985).

Constructing a Control Group Using Multivariate Matched Sampling Methods That Incorporate the

Propensity Score.

The American Statistician, 39(1):33–38.

[Samuels and Greevy, 2018] Samuels, L. R. and Greevy, R. A. (2018).

Bagged one-to-one matching for efficient and robust treatment effect estimation.

Stat Med, 37(29):4353–4373.

[Sato and Matsuyama, 2003] Sato, T. and Matsuyama, Y. (2003).

Marginal structural models as a tool for standardization.

Epidemiology, 14(6):680–686.

[Shah et al., 2018] Shah, S., Norby, F. L., Datta, Y. H., Lutsey, P. L., MacLehose, R. F., Chen, L. Y.,

and Alonso, A. (2018).

Comparative effectiveness of direct oral anticoagulants and warfarin in patients with cancer and atrial

fibrillation.

Blood Adv, 2(3):200–209.

[Solomon et al., 2010] Solomon, D. H., Rassen, J. A., Glynn, R. J., Lee, J., Levin, R., and

Schneeweiss, S. (2010).

The comparative safety of analgesics in older adults with arthritis.

Arch. Intern. Med., 170(22):1968–1976.

6 / 7](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slidesonline-190318233323/85/Propensity-Score-Methods-for-Comparative-Effectiveness-Research-with-Multiple-Treatment-Groups-50-320.jpg)

![Bibliography V

[Stürmer et al., 2010] Stürmer, T., Rothman, K. J., Avorn, J., and Glynn, R. J. (2010).

Treatment effects in the presence of unmeasured confounding: Dealing with observations in the tails

of the propensity score distribution–a simulation study.

Am. J. Epidemiol., 172(7):843–854.

[Walker et al., 2013] Walker, A. M., Patrick, A. R., Lauer, M. S., Hornbrook, M. C., Marin, M. G.,

Platt, R., Roger, V. L., Stang, P., and Schneeweiss, S. (2013).

A tool for assessing the feasibility of comparative effectiveness research.

Comp Eff Res, 2013(3):11–20.

[Yoshida et al., 2017] Yoshida, K., Hernandez-Diaz, S., Solomon, D. H., Jackson, J. W., Gagne, J. J.,

Glynn, R. J., and Franklin, J. M. (2017).

Matching Weights to Simultaneously Compare Three Treatment Groups: Comparison to Three-way

Matching.

Epidemiology, 28(3):387–395.

[Yoshida et al., 2019] Yoshida, K., Solomon, D. H., Haneuse, S., Kim, S. C., Patorno, E., Tedeschi,

S. K., Lyu, H., Franklin, J. M., Stürmer, T., Hernández-Díaz, S., and Glynn, R. J. (2019).

Multinomial Extension of Propensity Score Trimming Methods: A Simulation Study.

Am. J. Epidemiol., 188(3):609–616.

[Zeng et al., 2019] Zeng, C., Dubreuil, M., LaRochelle, M. R., Lu, N., Wei, J., Choi, H. K., Lei, G.,

and Zhang, Y. (2019).

Association of Tramadol With All-Cause Mortality Among Patients With Osteoarthritis.

JAMA, 321(10):969–982.

7 / 7](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slidesonline-190318233323/85/Propensity-Score-Methods-for-Comparative-Effectiveness-Research-with-Multiple-Treatment-Groups-51-320.jpg)