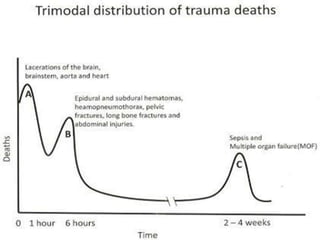

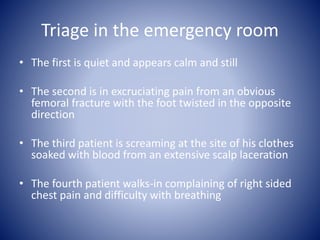

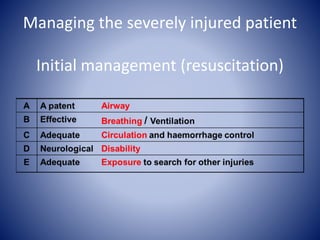

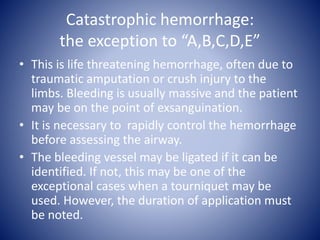

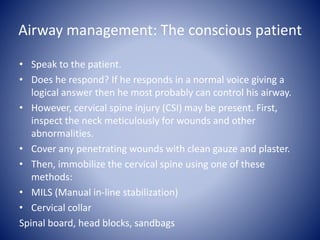

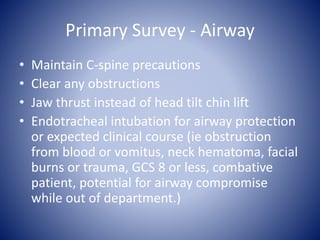

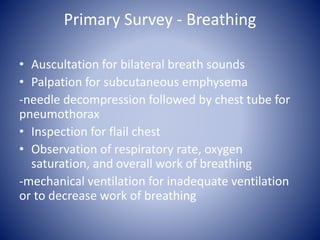

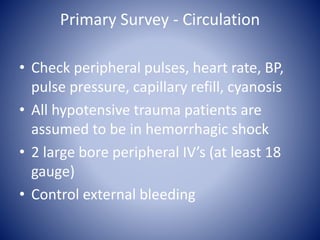

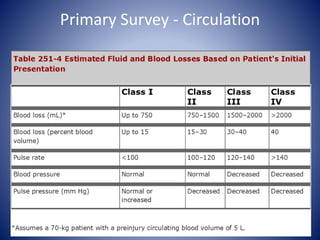

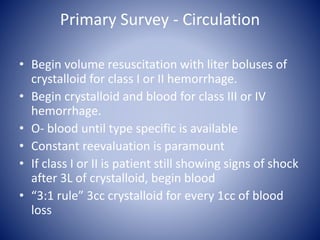

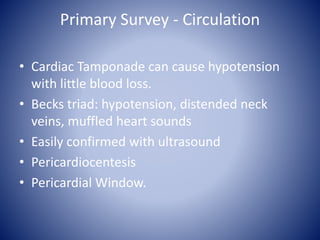

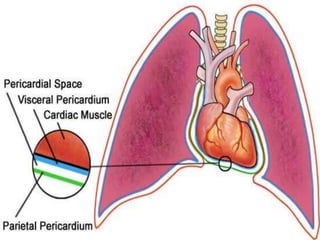

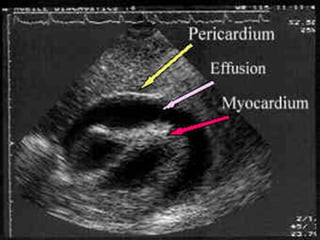

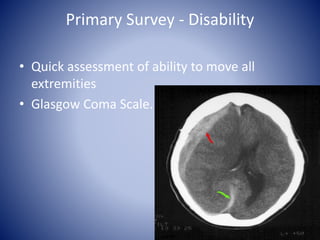

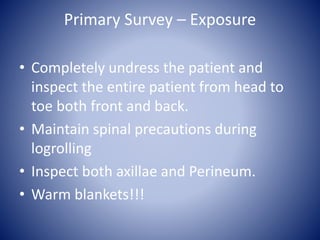

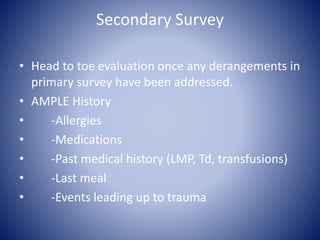

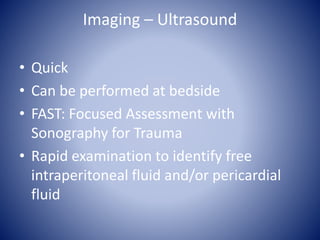

This document discusses primary trauma care and outlines the steps for assessing and managing trauma patients. It covers triaging patients, performing a primary and secondary survey, identifying life-threatening injuries, providing initial resuscitation and stabilization, and determining appropriate disposition. The primary goals are to assess and treat airway, breathing, circulation and disability issues; control hemorrhage; and identify injuries requiring surgical intervention. Proper trauma management in the first hours can significantly impact outcomes.