This document provides guidance on airway management for clinicians during Hajj. It discusses manual airway opening techniques like head tilt/chin lift and jaw thrust. Adjuncts like oropharyngeal and nasopharyngeal airways are also described. Definitive airways include endotracheal tubes, which require rapid sequence induction and confirmation of proper placement. Nasotracheal intubation and surgical airways like cricothyroidotomy are also summarized as alternatives when other methods fail or in specific injury cases. Maintaining a clear airway is a top clinical priority to allow for breathing and oxygenation.

![A POCKET GUIDE FOR CLINICIANS DURING HAJJ

28

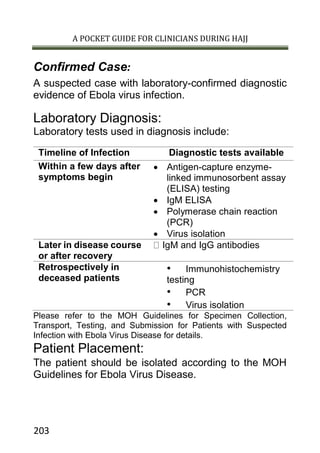

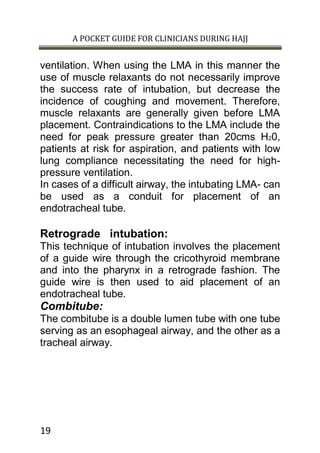

Acute respiratory failure

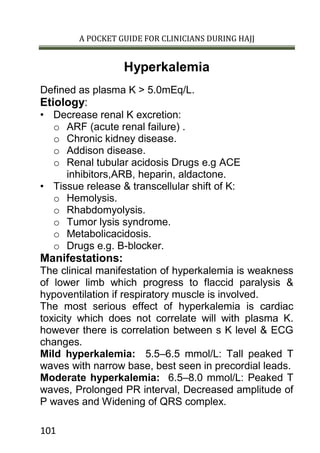

There are two types of respiratory failure:

Type I: the most common form of respiratory failure is

Hypoxemic respiratory failure which is characterized by a

PaO2 of less than 60 mm Hg with a normal or low PaCO2.

and it can be associated with all acute diseases of the lung,

which generally involve fluid filling or collapse of alveolar

units. Some examples of type I respiratory failure are

cardiogenic or noncardiogenic pulmonary edema,

pneumonia, and pulmonary hemorrhage.

type II : Hypercapnic respiratory failure is characterized

by a PaCO2 of more than 50 mm Hg. And commonly

associated with Hypoxemia, The pH depends on the level

of bicarbonate, which is dependent on the duration of

hypercapnia. Common etiologies include drug overdose,

neuromuscular disease, chest wall abnormalities, and

severe airway disorders (eg, asthma, chronic obstructive

pulmonary disease [COPD]).

Manifestations:

Altered mental status

Increased work of breathing

o Tachypnea

o Accessory muscle use, retractions, paradoxical

breathing pattern

Catecholamine release

o Tachycardia, diaphoresis, hypertension

Abnormal arterial blood gas values](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/hajjpocketguide-150613001804-lva1-app6892/85/Hajj-pocket-guide-29-320.jpg)

![A POCKET GUIDE FOR CLINICIANS DURING HAJJ

105

meq/L/hour, in 1st

few hours. Serum Na should not

exceed >12meq/24h.

• 1ml of 3% NaCl /kg/h - increase serum Na 1meq/l/h.

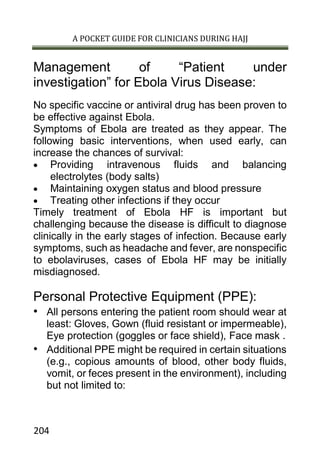

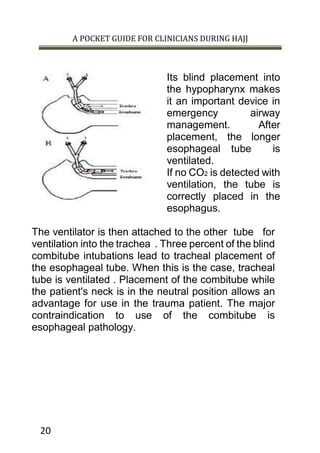

Hypernatremia

Defined as serum Na > 145meq/L.

Etiologies of hypernatremia:

Hyponatremia secondary to water loss (commonest

cause).

o Nonrenal water loss e.g. GIT loss , burn.

o renal water loss e.g. osmotic dieresis like in

hyperglycemia , Manitol & Diabetes inspidus (

CDI,NDI).

Impaired thirst:

o Intubated patient in ICU.

o Patient with impaired mental status.

o Physically handicapped.

Hyponatremia due to Na gain:

o In Patient with DKA &osmotic dieresis treated

with N saline.

o Treatment with IV NaHCO3 during resuscitation.

Manifestations:

• Mainly neurological include altered mental status,

weakness, Coma& seizure.

• H2O deficit (L) =[0.6 wt (kg) ] [measured Na - 1]140

Treatment:

• Stop ongoing water loss.

• Correct water deficit.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/hajjpocketguide-150613001804-lva1-app6892/85/Hajj-pocket-guide-106-320.jpg)

![A POCKET GUIDE FOR CLINICIANS DURING HAJJ

108

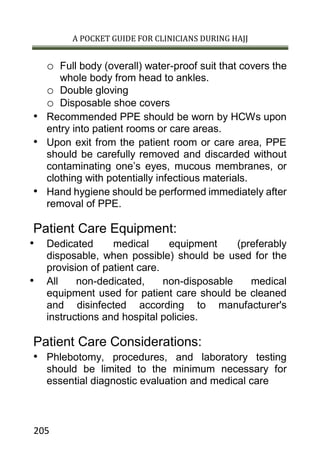

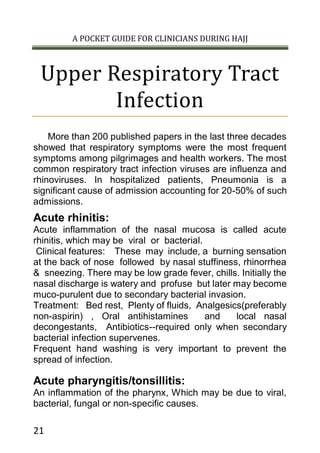

Normal anion gap : 9 ± 3 mEq /L

Reveal additional information on albumin level.

Note that an AG acidosis can exist even when the AG

is normal; this is particularly true in critically ill

patients with low albumin.

Expected AG decreases by 2.5-3 mmol/L for

every 1 g/dL decrease in albumin

Calculate the delta gap if a metabolic acidosis is

present.

Δgap = (deviation of AG from normal)– (deviation

of [HCO3] from normal)

Accurate analysis should lead to early interventions.

Metabolic Acidosis

Mechanisms:

Increased acid intake orIncreased acid production,

so, exceeding renal acid excretion (e.g. ketoacidosis

or lactic acidosis).

Renal acid excretion fails to match endogenous acid

production (e.g Renal Tubular Acidosis).

Decreased bicarbonate by GIT loss (e.g. diarrhea or

fistula).

Types of metabolic acidosis:

Normal anion gap metabolic acidosis:

o Causes:

- RTA (Renal Tubular Acidosis).

- Loss of HCO3- from GIT as in :

- Diarrhea - Uretral diversion

- ileostomy.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/hajjpocketguide-150613001804-lva1-app6892/85/Hajj-pocket-guide-109-320.jpg)

![A POCKET GUIDE FOR CLINICIANS DURING HAJJ

202

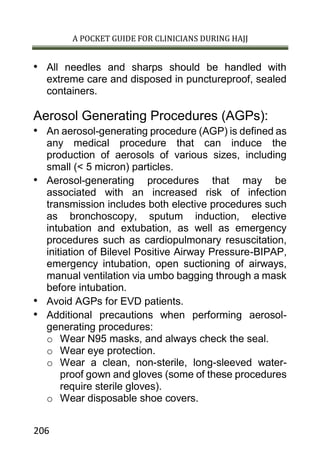

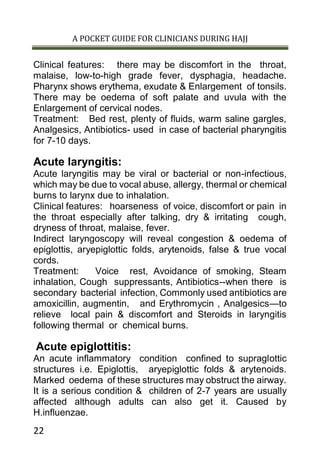

Ebola Virus Disease

(EVD)

Case Definition for Ebola Virus Disease:

Suspected Case:

Illness in a person who has both consistent symptoms

and risk factors as follows:

Clinical criteria, which includes fever of greater than

38.6O

C, and additional symptoms such as severe

headache, muscle pain, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal

pain, or unexplained hemorrhage (gingival, nasal,

cutaneous [petechiae, bruises, ecchymosis],

gastrointestinal, rectal [gross or occult blood], urinary

[gross or microscopic hematuria], vaginal, or puncture

sites bleeding); AND Epidemiologic risk factors within

the past 3 weeks before the onset of symptoms, such as

contact with blood or other body fluids of a patient

known to have or suspected to have EVD; residence

in—or travel to—an area where EVD transmission is

active; or direct handling of dead or alive fruit bats,

monkeys, chimpanzees, gorillas, forest antelope and

porcupines from disease-endemic areas. Malaria

diagnostics should also be a part of initial testing

because it is a common cause of febrile illness in

persons with a travel history to the affected countries.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/hajjpocketguide-150613001804-lva1-app6892/85/Hajj-pocket-guide-203-320.jpg)