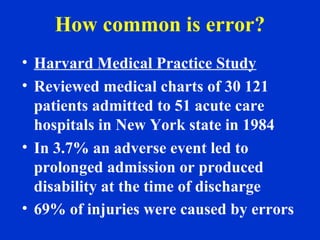

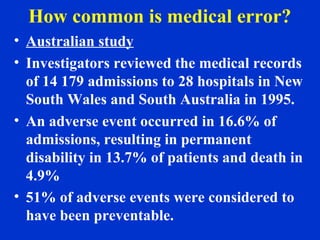

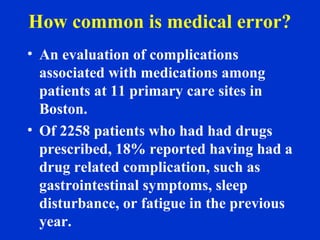

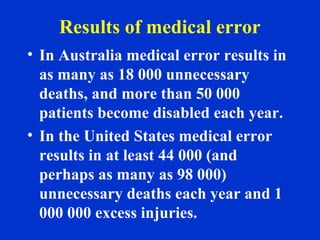

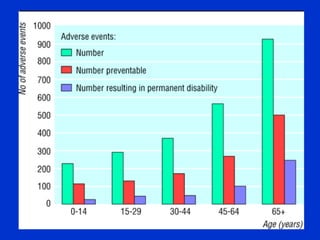

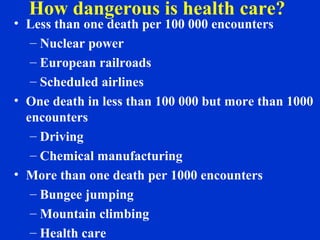

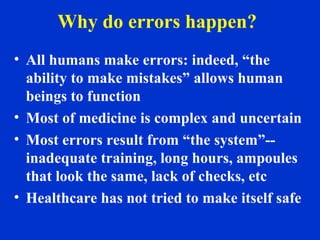

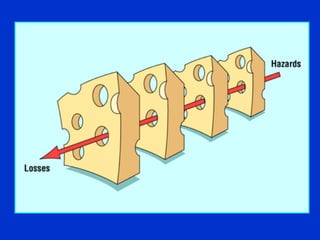

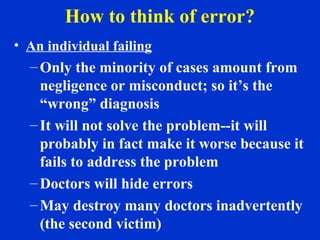

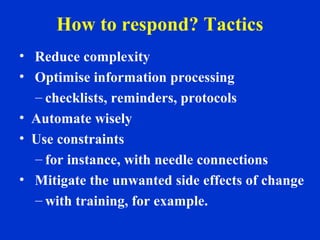

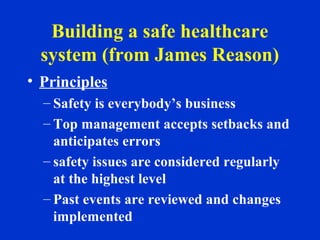

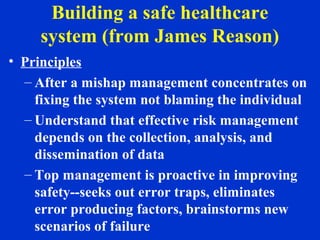

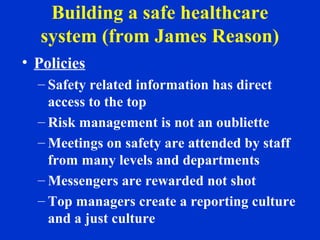

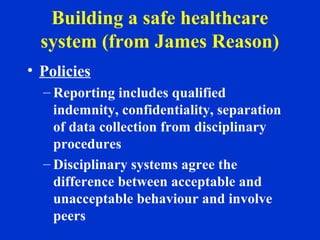

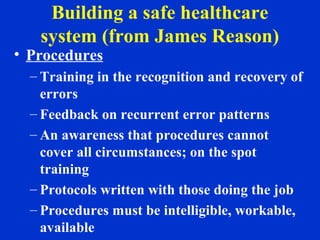

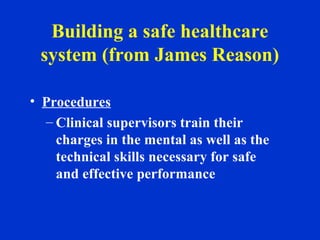

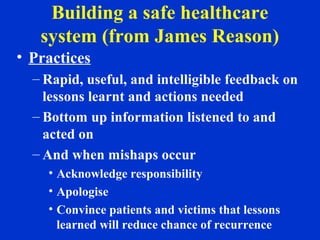

This document discusses medical errors and increasing patient safety. It summarizes several studies that found medical errors are common, with rates of adverse events from around 3-17% of hospital admissions. Errors result in tens of thousands of unnecessary deaths annually. Most errors are due to cognitive mistakes and "system" failures rather than individual negligence. To improve safety, the document argues we must think of errors as systems failures and implement strategies like checklists, standardized procedures, training, and a culture where safety is a top priority and errors are reported to fix underlying issues rather than blame individuals.