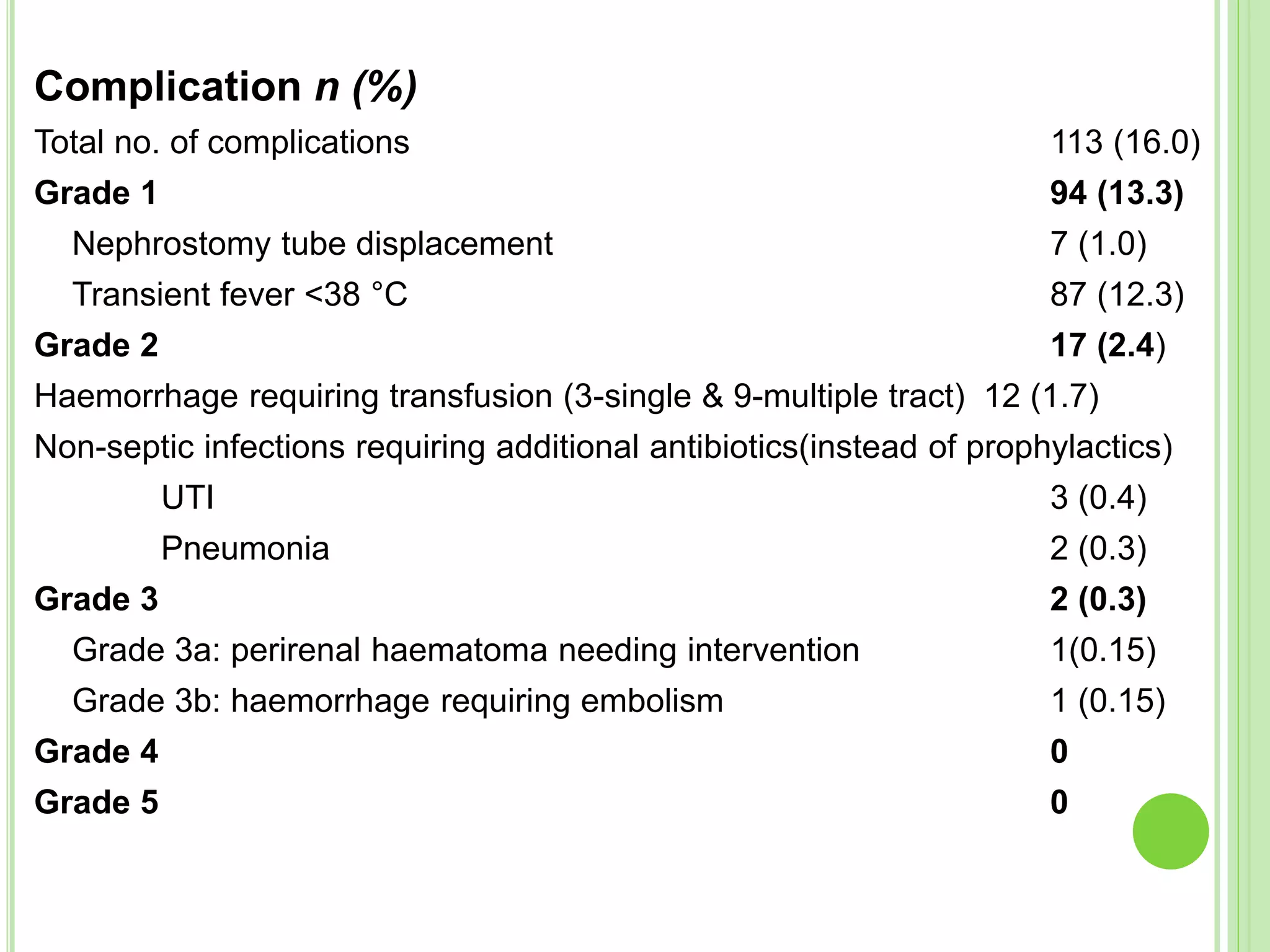

This study evaluated the safety and efficacy of percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL) guided solely by ultrasonography in over 700 cases over 5 years. Access to the pelvicalyceal system was successful in all cases using ultrasonography. The overall stone-free rate was 87.4% and complications were minor, with a low 16% rate. The study demonstrated that PCNL can be performed safely and effectively using only ultrasonography guidance, avoiding the risks of radiation exposure from fluoroscopy.

![INTRODUCTION

Percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL) has been

performed as a minimally invasive method of

removing kidney stones since 1976.

Because of the improvements in technique and

equipment, PCNL is now considered to be a

generally safe management option, with a low

incidence of complications [1,2]

1. Wen CC, Nakada SY. Treatment selection and outcomes: renal

calculi. Urol Clin North Am 2007; 34: 409–19

2. Lingeman JE, Miller NL. Management of kidney stones. BMJ

2007; 334: 468–72](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pcnl-150819145642-lva1-app6891/75/Percutaneous-Nephrolithotomy-5-2048.jpg)

![ Pelvicalyceal system (PCS) access is key to

successful PCNL and is generally performed under

fluoroscopic guidance.

Although protective gowns can be used by patients

and physicians during these procedures, radiation

exposure can still affect the surgical team over the

long term, and the hazard is dose-independent [3].

3. Safak M, Olgar T, Bor D, Berkmen G, Gogus C. Radiation doses

of patients and urologists during percutaneous

nephrolithotomy. J Radiol Prot 2009; 29: 409–15](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pcnl-150819145642-lva1-app6891/75/Percutaneous-Nephrolithotomy-6-2048.jpg)

![ The use of ultrasonography (US) can avoid

radiation exposure and provides a reliable method

for the localization of renal stones, especially non-

opaque stones that are not visible via fluoroscopy.

Moreover, colour US can be used as a tool for the

localization of intrarenal arteries and helps to avoid

their puncture by a Chiba needle [4,5].

4. Lu M-H, Pu X-Y, Gao X, Zhou X-F, Qiu J-G, Tu S-T. Comparative study of

clinical value of single B-mode ultrasound guidance and B-mode combined

with color Doppler ultrasound guidance in mini-invasive percutaneous

nephrolithotomy to decrease hemorrhagic complications. Urology 2010; 76:

815–20

5. Tzeng B-C, Wang C-J, Huang S-W, Chang C-H. Doppler ultrasound-guided

percutaneous nephrolithotomy: a prospective randomized study. Urology

2011; 78: 535–9](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pcnl-150819145642-lva1-app6891/75/Percutaneous-Nephrolithotomy-7-2048.jpg)

![ Osman et al. [6] suggested that PCNL punctures should be

carried out under US guidance; however, they completed

the rest of the procedure under fluoroscopic guidance.

Some studies [7,8] have recommended the use of PCNL

guided solely by US for single stones in moderately to

markedly dilated PCSs by an experienced urologist

6. Osman M, Wendt-Nordahl G, Heger K, Michel MS, Alken P, Knoll T.

Percutaneous nephrolithotomy with ultrasonography- guided renal access:

experience from over 300 cases. BJU Int 2005; 96: 875–8

7. Hosseini M, Hassanpour A, Farzan R, Yousefi A, Afrasiabi MA.

Ultrasonography guided percutaneous nephrolithotomy. J Endourol 2009;

23: 603–7

8. Gamal WM, Hussein M, Aldahshoury M, Hammady A, Osman M, Moursy E,

Abuzeid A. Solo ultrasonography-guided percutanous nephrolithotomy for

single stone pelvis. J Endourol 2011; 25: 593–6](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pcnl-150819145642-lva1-app6891/75/Percutaneous-Nephrolithotomy-8-2048.jpg)

![ Mayank et al. [9] suggested US as an adjunct to

fluoroscopy for renal access in PCNL; however, a

large series is still needed to prove the safety and

efficiency of PCNL guided solely by US in various

stone cases. In the present study, we reported our

experience and evaluated the feasibility and

efficacy of PCNL performed solely under US

guidance.

9. Agarwal M, Agrawal MS, Jaiswal A, Kumar D, Yadav H, Lavania P. Safety

and efficacy of ultrasonography as an adjunct to fluoroscopy for renal

access in percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL). BJU Int 2011; 108:

1346–9](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pcnl-150819145642-lva1-app6891/75/Percutaneous-Nephrolithotomy-9-2048.jpg)

![PATIENTS AND METHODS

From May 2007 to July 2012, 705 24-F-tract PCNL

procedures were performed (679 patients, of whom

26 had bilateral stones).

Calyceal puncture and dilatation were performed

under US guidance in all cases.

The procedure was evaluated for access success,

length of postoperative hospital stay, complications

(modified Clavien system) [10], stone clearance

and the need for auxiliary treatments.

10. de la Rosette JJ, Opondo D, Daels FP et al. Categorisation of

complications and validation of the Clavien score for

percutaneous nephrolithotomy. Eur Urol 2012; 62: 246–55](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pcnl-150819145642-lva1-app6891/75/Percutaneous-Nephrolithotomy-10-2048.jpg)

![DISCUSSION

Percutaneous nephrolithotomy is the primary procedure

for the management of patients with renal stones who

are not candidates for ESWL.

Fluoroscopic guidance has been used to guide the

percutaneous renal access, establish the working tract

and perform the stone manipulation.

The use of US guidance has other advantages in

addition to being free of ionizing radiation; for example,

it results in fewer punctures, has shorter operating times

and avoids contrast-related complications [12].

12. Basiri A, Ziaee SA, Nasseh H et al. Totally ultrasonography guided

percutaneous nephrolithotomy in the flank position. J Endourol 2008;

22: 1453–7](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pcnl-150819145642-lva1-app6891/75/Percutaneous-Nephrolithotomy-27-2048.jpg)

![ This form of guidance allows imaging of the intervening

structures with the benefit of minimizing the risk of injury

to nearby organs.

Moreover, the use of US at the end of the procedure

helps the urologist to look for non-opaque and semi-

opaque residual stones that are not visualized by

radiography [13].

The European Association of Urology recommends

initial puncture under US guidance because it reduces

radiation hazards [14].

13. Basiri A, Ziaee A, Kianian H, Mehrabi S, Karami H, Moghaddam S.

Ultrasonographic versus Fluoroscopic Access for Percutaneous

Nephrolithotomy: a Randomized Clinical Trial. J Endourol 2008; 22: 281-

4

14. European Association of Urology. Guidelines on urolithiasis. 2012

http://www.uroweb.org/gls/pdf/21_Urolithiasis_LR.pdf](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pcnl-150819145642-lva1-app6891/75/Percutaneous-Nephrolithotomy-28-2048.jpg)

![ 100% access to the kidney as well as 87.4% complete

stone clearance, were achieved. The stone-free rate in

this series was comparable with the rates gained from

PCNL results reported in other series under either US or

fluoroscopic guidance [15,16].

Osman et al. [17] reported that the sensitivity of plain

abdominal film of kidney, ureter and bladder (KUB) for

detecting stone-free rates was 40.3% and that of US

was 37.1%.

15. Shoma AM, Eraky I, El-Kenawy M, El-Kappany HA. Percutaneous

nephrolithotomy in the supine position: technical aspects and

functional outcome compared with the prone technique. Urology 2002;

60: 388–92

16. Basiri A, Mohammadi Sichani M, Hosseini SR et al. X-ray-free

percutaneous nephrolithotomy in supine position with ultrasound

guidance.World J Urol 2010; 28: 239–44

17. Osman Y, El-Tabey N, Refai H et al. Detection of residual stones

after percutaneous nephrolithotomy: role of non-enhanced spiral

computerized tomography. J Urol 2008; 179: 198–200](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pcnl-150819145642-lva1-app6891/75/Percutaneous-Nephrolithotomy-30-2048.jpg)

![ The sensitivities of KUB and US for detecting significant

residual stones were reported to be 58.3 and 41.6%,

respectively; for detecting CIRFs, the reported

sensitivities were 15.3 and 30.7%, respectively;

however, Alan et al. [18] reported that the sensitivities of

US for detecting significant residual stones and CIRFs

were 83.3 and 87.5%, respectively, based on KUB

detection.

In their study, the stone-free status was double-checked

during the operation using a flexible nephroscope and

US, but CT was also routinely performed to confirm the

residual stone status on the second postoperative day.

18. Alan C, Kocoğlu H, Ates F, Ersay AR. Ultrasound-guided X-ray free

percutaneous nephrolithotomy for treatment of simple stones in the

flank position. Urol Res 2011; 39: 205–12](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pcnl-150819145642-lva1-app6891/75/Percutaneous-Nephrolithotomy-31-2048.jpg)

![ Percutaneous nephrolithotomy is usually performed with the

patient in a prone position, but this prone position has several

disadvantages. For example, PCNL with the patient in this

position is difficult when the patient is obese or has spinal

anomalies or cardiovascular disease [19].

Karami et al. [20] reported performing PCNL under US guidance

in 40 patients in the lateral position with an access rate of 100%

and a complete stone-removal rate of 85%.

In the present study, PCNL was performed in the lateral position

for the 53 patients who had insufficient cardiac output or

pulmonary disease and US guidance was proven to be a safe

and convenient procedure in both positions.

19. Manohar T, Jain P, Desai M. Supine percutaneous nephrolithotomy: effective approach

to high-risk and morbidly obese patients. J Endourol 2007; 21: 44–9

20. Karami H, Arbab AH, Rezaei A, Mohammadhoseini M, Rezaei I. Percutaneous

nephrolithotomy with ultrasonography-guided renal access in the lateral decubitus

flank position. J Endourol 2009; 23: 33–5](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pcnl-150819145642-lva1-app6891/75/Percutaneous-Nephrolithotomy-32-2048.jpg)