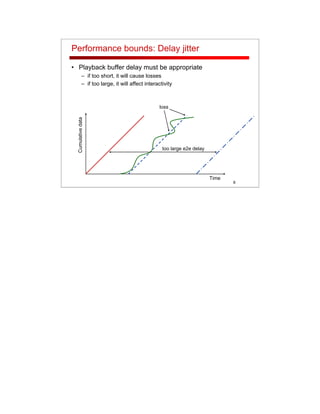

This document discusses packet scheduling for quality of service (QoS) management in multi-service networks. It describes common performance bounds like maximum delay and delay jitter. First-come first-served scheduling is discussed along with its limitations. Priority queuing and max-min fair sharing are presented as alternatives to provide traffic isolation and fair resource sharing. The concept of a scheduler's schedulable region for efficient admission control is also introduced.