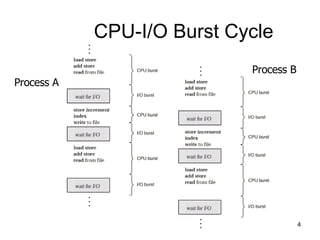

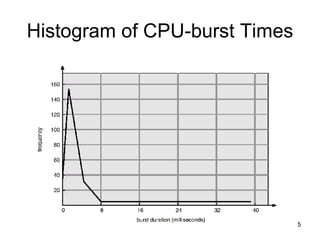

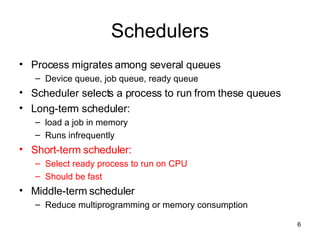

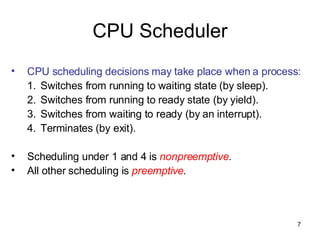

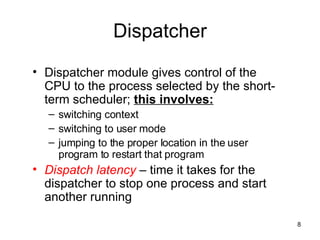

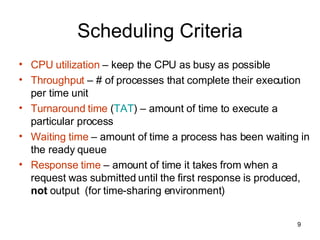

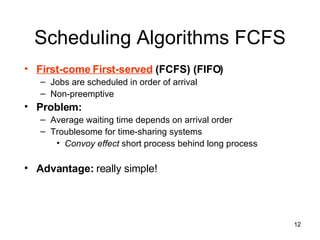

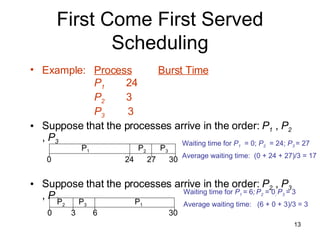

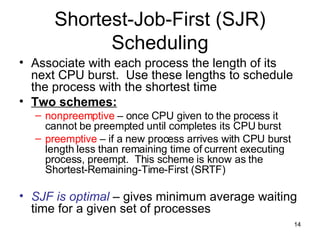

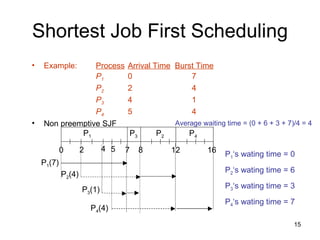

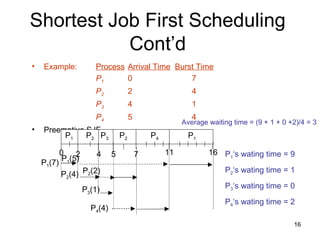

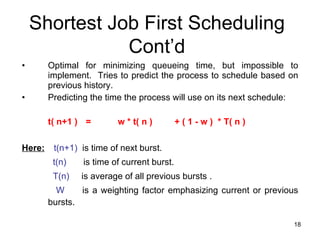

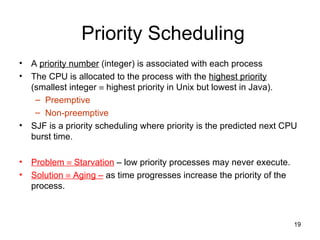

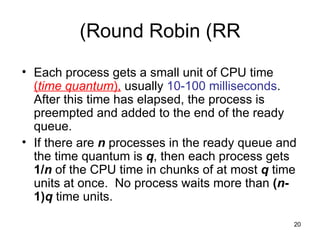

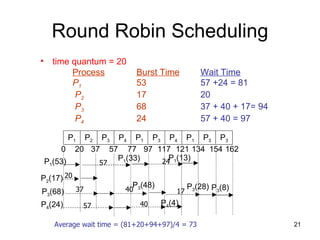

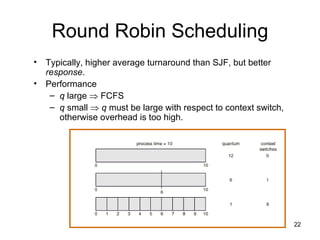

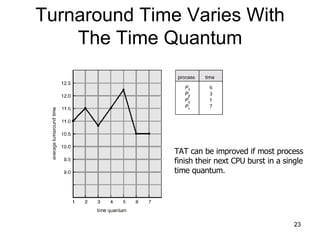

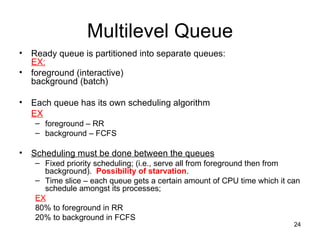

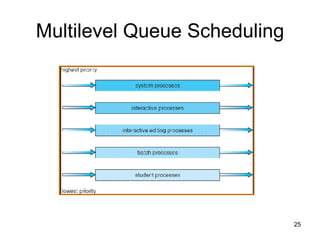

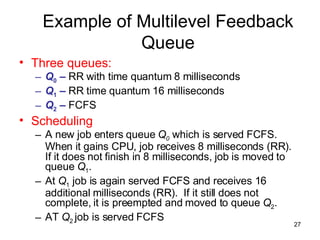

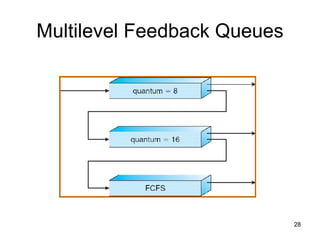

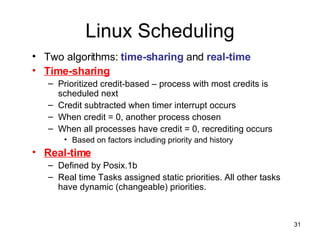

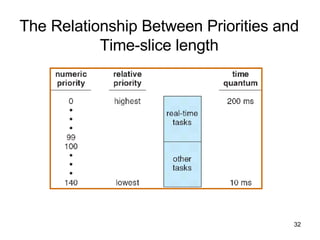

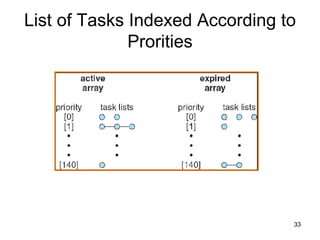

The document discusses various CPU scheduling concepts and algorithms. It covers basic concepts like CPU-I/O burst cycles and scheduling criteria. It then describes common scheduling algorithms like first come first served (FCFS), shortest job first (SJF), priority scheduling, and round robin (RR). It also discusses more advanced topics like multi-level queue scheduling, multi-processor scheduling, and thread scheduling in Linux.