The document discusses CPU scheduling, covering essential concepts, criteria, algorithms, and the management of deadlocks. It details various scheduling algorithms such as First-Come-First-Served, Shortest Job First, Priority Scheduling, and Round Robin, each with explanations of their mechanics and examples. Additionally, the document addresses issues like preemptive vs non-preemptive scheduling and introduces advanced concepts like multilevel queue and multilevel feedback queue scheduling.

![Dr.M.Sivakumar, AP/NWC, SRMIST 21

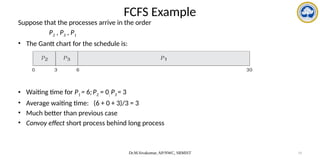

Example Preemptive SJF

• consider the following four processes, with the length of the CPU burst given in milliseconds:

• preemptive SJF schedule is as depicted in the following Gantt chart:

• The average waiting time = [(10-1-0) + (1-1) + (17-2) + (5-3)] / 4

= (9+0+15+2)/4 = 26/4 = 6.5 ms](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/operatingsystemscpuscheduling-241118113036-3be17652/85/Operating-Systems-CPU-Scheduling-and-its-Algorithms-21-320.jpg)

![Dr.M.Sivakumar, AP/NWC, SRMIST 26

Example of RR with Time Quantum = 4

• Consider the following set of processes that arrive at time 0, with the length of the CPU burst

given in milliseconds:

• The resulting RR schedule is as follows:

• The average waiting time = [(10-4) + 4 + 7] / 4 = 17/4 = 5.66 ms](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/operatingsystemscpuscheduling-241118113036-3be17652/85/Operating-Systems-CPU-Scheduling-and-its-Algorithms-26-320.jpg)

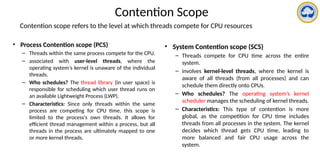

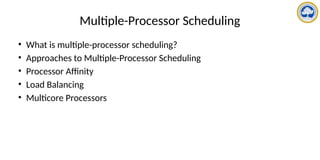

![Pthread scheduling API

#include <pthread.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#define NUM THREADS 5

int main(int argc, char *argv[])

{

int i, scope;

pthread t tid[NUM THREADS];

pthread attr t attr;

/* get the default attributes */

pthread attr init(&attr);

/* first inquire on the current scope */

if (pthread attr getscope(&attr, &scope) != 0)

fprintf(stderr, "Unable to get scheduling scopen");

else {

if (scope == PTHREAD SCOPE PROCESS)

printf("PTHREAD SCOPE PROCESS");

else if (scope == PTHREAD SCOPE SYSTEM)

printf("PTHREAD SCOPE SYSTEM");

else

fprintf(stderr, "Illegal scope value.n");

}

/* set the scheduling algorithm to PCS or SCS */

pthread attr setscope(&attr, PTHREAD SCOPE SYSTEM);

/* create the threads */

for (i = 0; i < NUM THREADS; i++)

pthread create(&tid[i],&attr,runner,NULL);

/* now join on each thread */

for (i = 0; i < NUM THREADS; i++)

pthread join(tid[i], NULL);

}

/* Each thread will begin control in this function */

void *runner(void *param)

{

/* do some work ... */

pthread exit(0);

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/operatingsystemscpuscheduling-241118113036-3be17652/85/Operating-Systems-CPU-Scheduling-and-its-Algorithms-46-320.jpg)

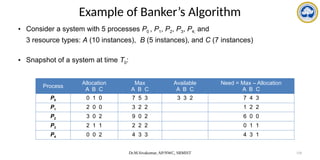

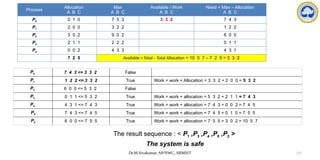

![Dr.M.Sivakumar, AP/NWC, SRMIST 122

Data Structures for the Banker’s Algorithm

• Available: Vector of length m. If available [j] = k, there are k instances of resource type

Rj available.

• Max: n x m matrix. If Max [i,j] = k, then process Pi may request at most k instances of

resource type Rj.

• Allocation: n x m matrix. If Allocation[i,j] = k then Pi is currently allocated k instances

of Rj.

• Need: n x m matrix. If Need[i,j] = k, then Pi may need k more instances of Rj to

complete its task.

Need [i,j] = Max[i,j] – Allocation [i,j].

To encode the state of Resource Allocation

Let n = number of processes, and m = number of resources types.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/operatingsystemscpuscheduling-241118113036-3be17652/85/Operating-Systems-CPU-Scheduling-and-its-Algorithms-122-320.jpg)

![Dr.M.Sivakumar, AP/NWC, SRMIST 123

• Data structures – vary over time in both size and value

• To simplify the process of banker’s alg.

X,Y vectors of length n

X<=Y only if X[i] <= Y[i] for all i=1,2…n

• Treat each row in the matrices Allocation and Need as vectors namely,

Allocationi – resources currently allocated to Pi

Needi – additional resource that Pi may still request to complete its task](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/operatingsystemscpuscheduling-241118113036-3be17652/85/Operating-Systems-CPU-Scheduling-and-its-Algorithms-123-320.jpg)

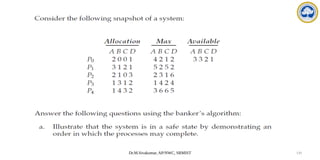

![Dr.M.Sivakumar, AP/NWC, SRMIST 124

Safety Algorithm

1. Let Work and Finish be vectors of length m and n, respectively.

Initialize: Work = Available and Finish [i] = false for i = 0, 1, …, n- 1.

2. Find an index i such that both:

(a) Finish [i] == false

(b) Needi Work

If no such i exists, go to step 4.

3. Work = Work + Allocationi

Finish[i] = true

go to step 2.

4. If Finish [i] == true for all i, then the system is in a safe state.

Safety algorithm may require an order of mxn2

operations to decide whether a state is safe](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/operatingsystemscpuscheduling-241118113036-3be17652/85/Operating-Systems-CPU-Scheduling-and-its-Algorithms-124-320.jpg)

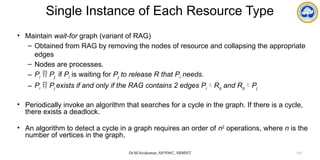

![Dr.M.Sivakumar, AP/NWC, SRMIST 125

Resource-Request Algorithm for Process Pi

Requesti = request vector for process Pi.

If Requesti [j] = k then process Pi wants k instances of resource type Rj.

• If safe the resources are allocated to Pi.

• If unsafe Pi must wait, and the old resource-allocation state is restored](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/operatingsystemscpuscheduling-241118113036-3be17652/85/Operating-Systems-CPU-Scheduling-and-its-Algorithms-125-320.jpg)

![Dr.M.Sivakumar, AP/NWC, SRMIST 134

Several Instances of a Resource Type

• Available: A vector of length m indicates the number of available resources of each

type.

• Allocation: An n x m matrix defines the number of resources of each type currently

allocated to each process.

• Request: An n x m matrix indicates the current request of each process. If Request

[ij] = k, then process Pi is requesting k more instances of resource type. Rj.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/operatingsystemscpuscheduling-241118113036-3be17652/85/Operating-Systems-CPU-Scheduling-and-its-Algorithms-134-320.jpg)

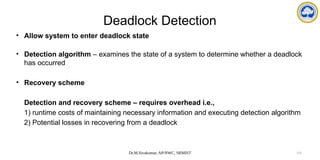

![Dr.M.Sivakumar, AP/NWC, SRMIST 136

Example of Detection Algorithm

• Five processes P0 through P4;three resource types

A = 7 instances, B = 2 instances, and C =6 instances

• Snapshot at time T0:

Allocation Request Available

A B C A B C A B C

P0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

P1 2 0 0 2 0 2

P2 3 0 3 0 0 0

P3 2 1 1 1 0 0

P4 0 0 2 0 0 2

• Sequence <P0, P2, P3, P1, P4> will result in Finish[i] = true for all i.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/operatingsystemscpuscheduling-241118113036-3be17652/85/Operating-Systems-CPU-Scheduling-and-its-Algorithms-136-320.jpg)