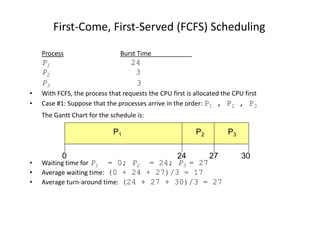

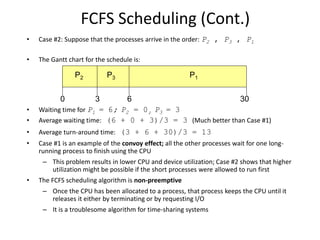

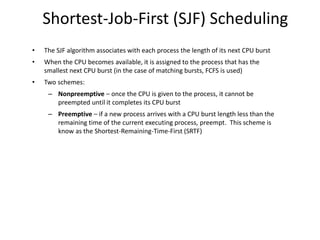

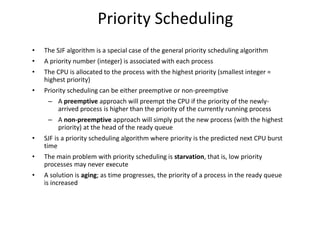

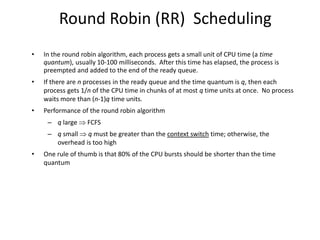

This document discusses CPU scheduling algorithms. It begins with basic concepts like multiprogramming and the alternating cycle of CPU and I/O bursts that processes undergo. It then covers key scheduling criteria like CPU utilization, throughput, waiting time and turnaround time. Several single processor scheduling algorithms are explained in detail, including first come first served (FCFS), shortest job first (SJF), priority scheduling, and round robin (RR). Examples are provided to illustrate how each algorithm works. Finally, it briefly introduces the concept of multi-level queue scheduling using multiple queues to classify different types of processes.

![Example #3: Preemptive SJF

(Shortest-remaining-time-first)

ProcessArrival Time Burst Time

P1 0.0 7

P2 2.0 4

P3 4.0 1

P4 5.0 4

• SJF (pre-emptive, varied arrival times)

• Average waiting time

= ( [(0 – 0) + (11 - 2)] + [(2 – 2) + (5 – 4)] + (4 - 4) + (7 – 5) )/4

= 9 + 1 + 0 + 2)/4

= 3

• Average turn-around time = (16 + 7 + 5 + 11)/4 = 9.75

P1 P3P2

42 110

P4

5 7

P2 P1

16

Waiting time : sum of time that a process has spent waiting in the ready queue](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ch05-cpu-scheduling-191104075904/85/Ch05-cpu-scheduling-21-320.jpg)

![Example of RR with Time Quantum =

20

Process Burst Time

P1 53

P2 17

P3 68

P4 24

• The Gantt chart is:

• Typically, higher average turnaround than SJF, but better response time

• Average waiting time

= ( [(0 – 0) + (77 - 20) + (121 – 97)] + (20 – 0) + [(37 – 0) + (97 - 57) + (134 – 117)] + [(57

– 0) + (117 – 77)] ) / 4

= (0 + 57 + 24) + 20 + (37 + 40 + 17) + (57 + 40) ) / 4

= (81 + 20 + 94 + 97)/4

= 292 / 4 = 73

• Average turn-around time = 134 + 37 + 162 + 121) / 4 = 113.5

P1 P2 P3 P4 P1 P3 P4 P1 P3 P3

0 20 37 57 77 97 117 121 134 154 162](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ch05-cpu-scheduling-191104075904/85/Ch05-cpu-scheduling-26-320.jpg)