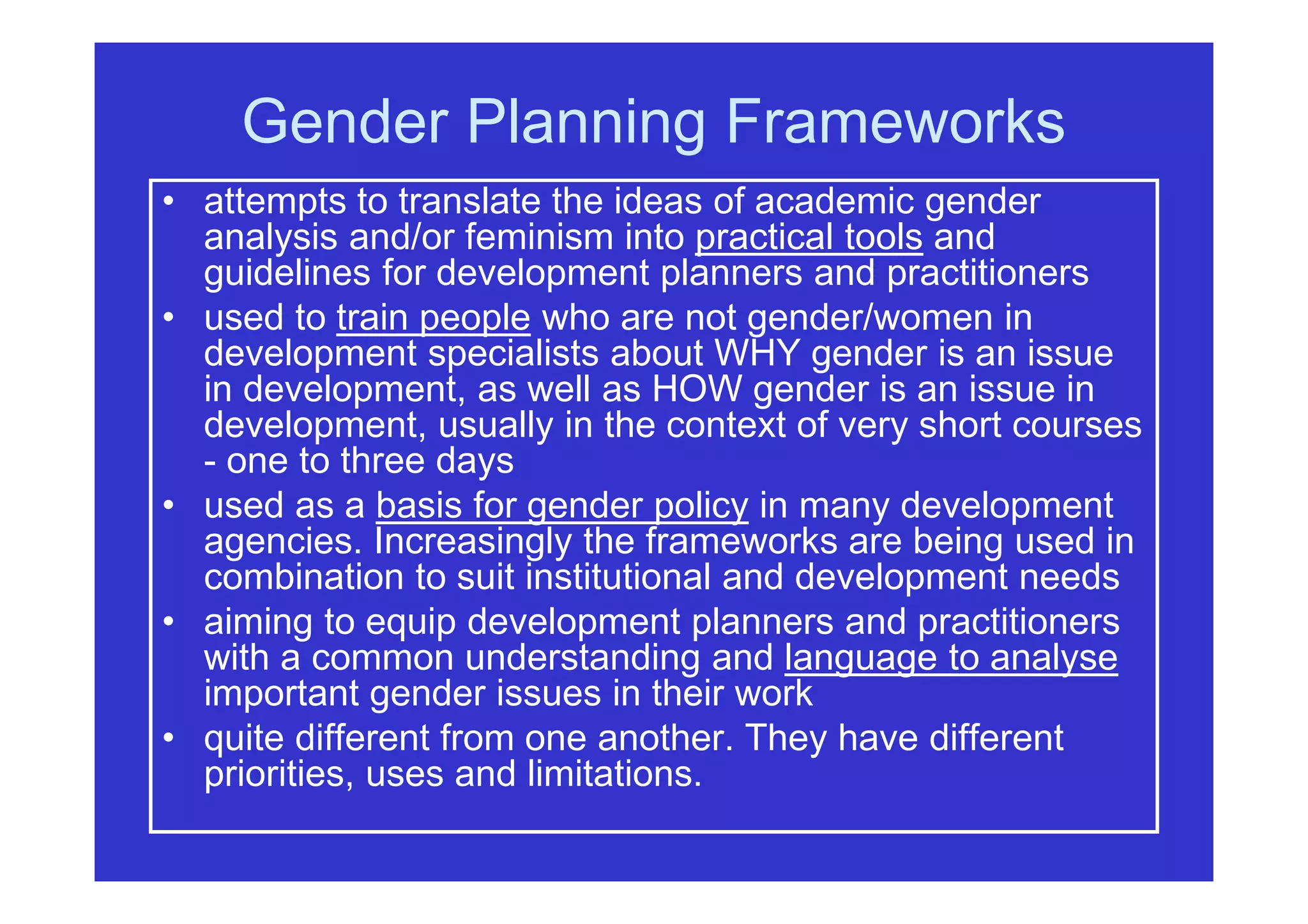

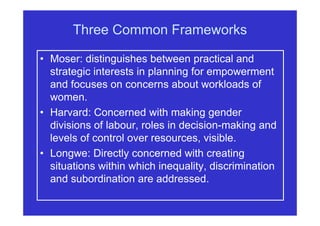

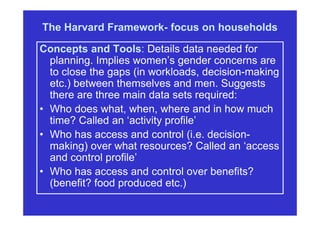

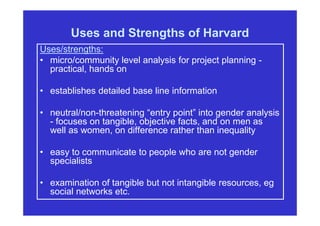

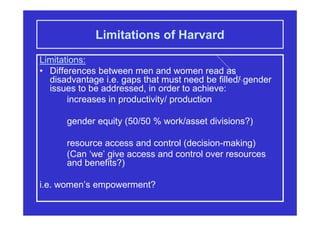

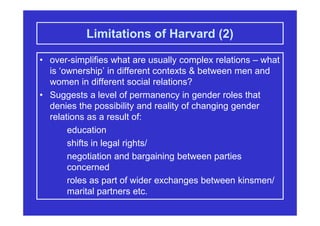

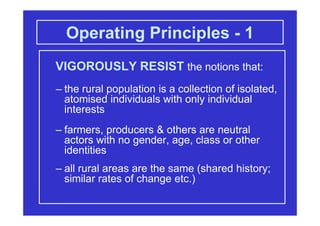

The document discusses gender planning frameworks designed to translate academic gender analysis into practical tools for development practitioners. It highlights various frameworks such as Moser, Harvard, and Longwe, each with distinct focuses, strengths, and limitations in analyzing gender relations and empowering women. The text emphasizes the importance of using these frameworks thoughtfully to stimulate critical thinking about gender issues in development planning.