The document provides a comprehensive overview of sleep disorders, including classifications such as insomnia, sleep apnea, and hypersomnia, along with their symptoms and causes. It discusses the pathophysiology of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), its risk factors, epidemiology, and various treatment options including CPAP therapy, medications, and surgery. Additionally, it highlights diagnostic criteria, evaluation methods like polysomnography, and other related sleep conditions.

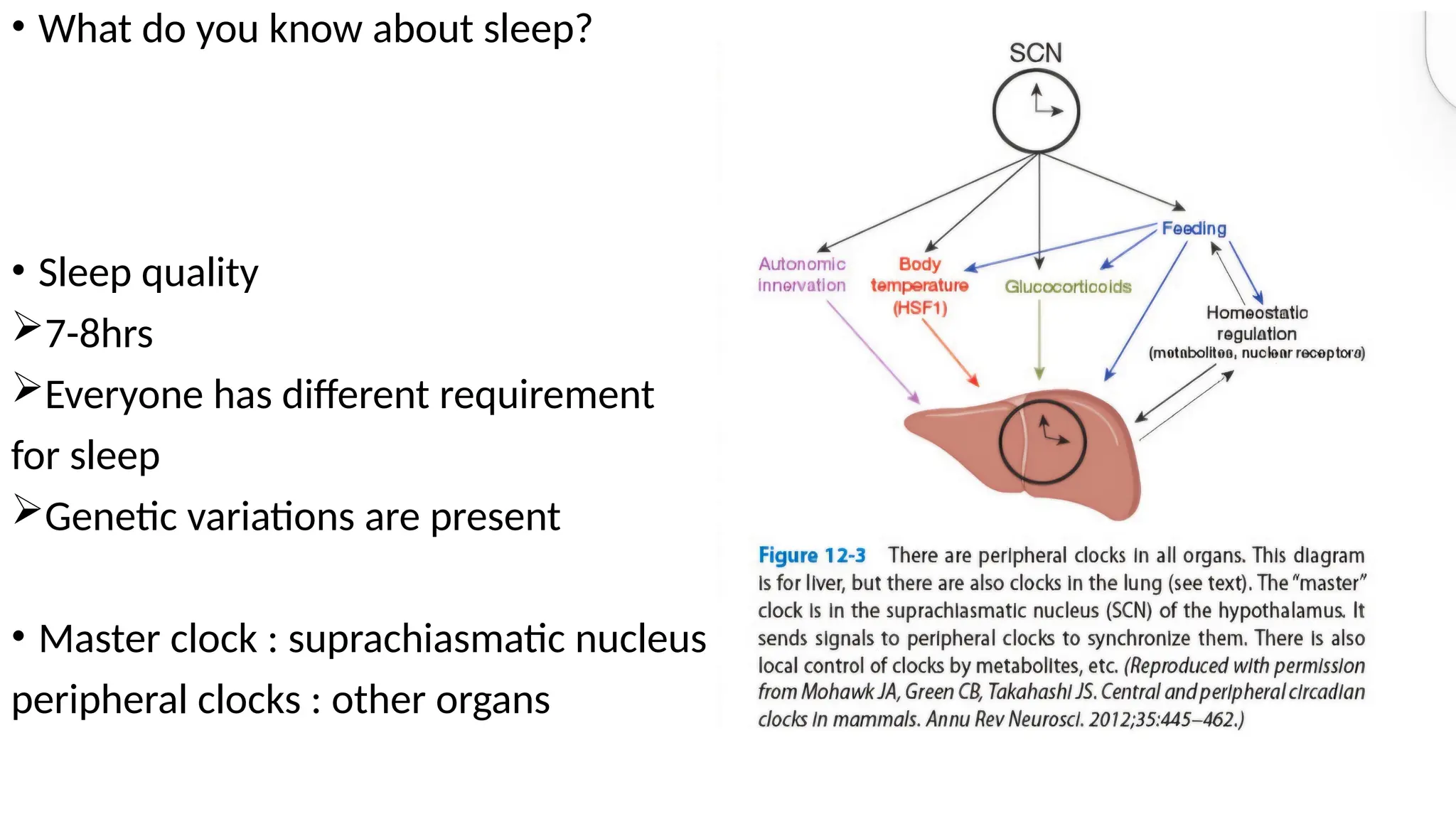

![Central sleep apnea

• CSA, in which repetitive episodes of breathing cessation occur in the absence of

respiratory effort, is characterized by reduced ventilatory motor output

• prevalence in the general population to be < 1%

1. Physiologic process in normal individuals in response to an arousal (especially

children and the elderly)

2. Manifestation of breathing instability in a number of medical conditions (e.g.,

Cheyne–Stokes respiration [CSR] in CHF and at high altitude)

3. In association with neurologic diseases such as Shy–Drager syndrome, stroke,

myasthenia gravis, neuromuscular disease, bulbar poliomyelitis, brainstem

infarction, and encephalitis.

• It is often divided into hypocapnic and hypercapnic types.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sleep1-240905065754-3dc3f271/75/Disorders-of-sleep-related-to-breathing-problems-29-2048.jpg)

![Obesity hypoventilation syndrome

defined by

• the presence of obesity (body mass index [BMI] ≥30 kg/m2),

• Chronic alveolar hypoventilation with daytime hypercapnia (awake PaCO2≥45

mm Hg)

• sleep-related breathing disorder in the absence of any other causes of

hypoventilation.

90% of OHS patients there is an associated sleep related breathing disorder, that is,

Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA);](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sleep1-240905065754-3dc3f271/75/Disorders-of-sleep-related-to-breathing-problems-39-2048.jpg)