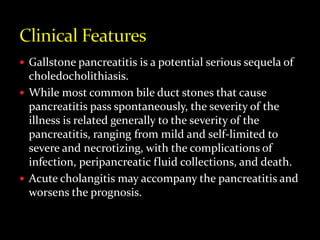

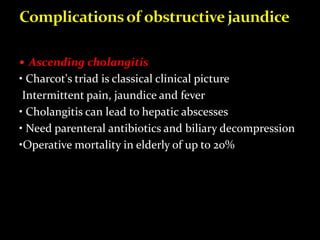

Common bile duct stones are found in 5-15% of patients undergoing cholecystectomy. They can cause obstruction, pain, jaundice, and cholangitis. Clinical features range from incidental findings to Charcot's triad of pain, fever, and jaundice. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography with sphincterotomy is the primary treatment for common bile duct stones.