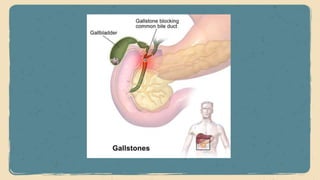

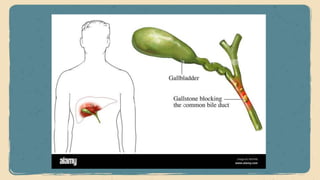

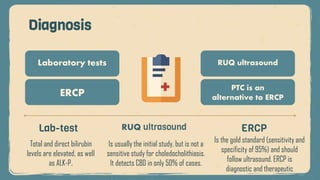

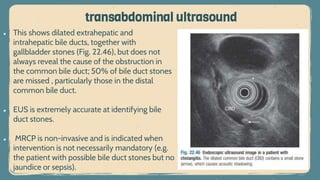

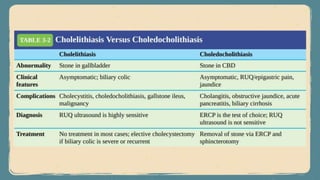

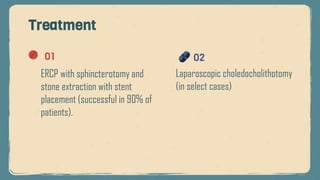

Choledocholithiasis involves stones in the common bile duct, occurring in 10-15% of gallstone patients, predominantly as secondary stones that migrate from the gallbladder. Clinical features can include abdominal pain, jaundice, and symptoms may vary from asymptomatic to acute conditions. Diagnosis typically involves ERCP as the gold standard, with treatment options including ERCP with sphincterotomy and laparoscopic choledocholithotomy in select cases.