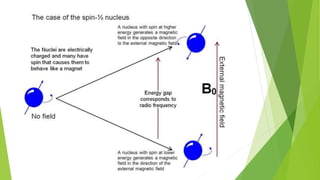

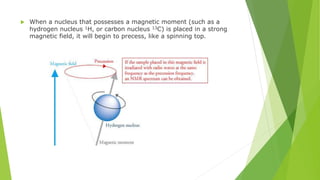

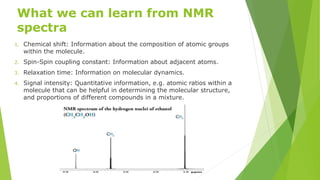

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) is a physical phenomenon where nuclei in a strong static magnetic field are perturbed by a weak oscillating magnetic field. The nuclei respond by producing an electromagnetic signal with a frequency characteristic of the magnetic field at the nucleus. NMR involves three steps - alignment of nuclear spins in a constant magnetic field, perturbation of the alignment with a radio-frequency pulse, and detection of the NMR signal during or after the pulse. NMR spectroscopy uses this technique to observe local magnetic fields around atomic nuclei and provides information about molecular structure, composition, and dynamics from properties of the detected NMR signal. NMR finds widespread applications in medicine, industrial analysis, and studies of molecular structures.