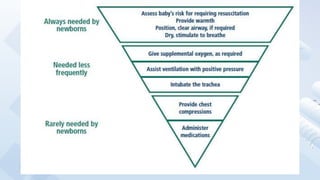

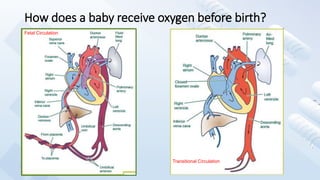

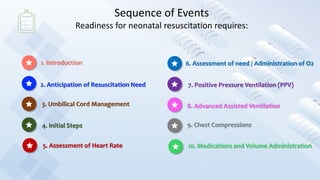

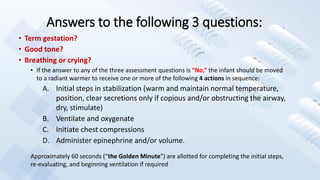

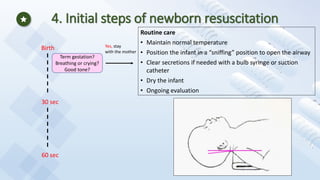

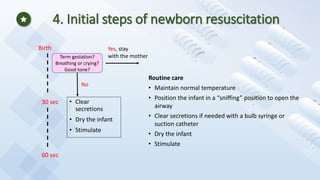

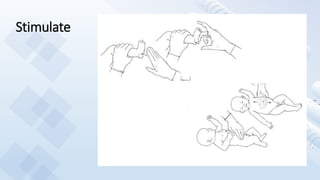

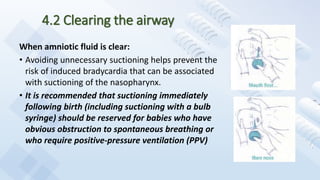

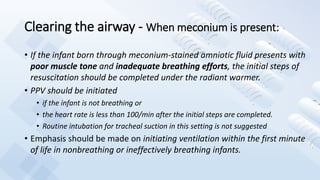

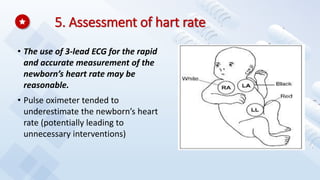

This document provides guidance on newborn resuscitation and delivery room management. It discusses the normal transition from fetal to newborn circulation at birth and signs that can indicate in utero or perinatal compromise requiring resuscitation. It outlines the initial steps of resuscitation including maintaining temperature, positioning, clearing secretions if needed, drying, and stimulating the newborn. It emphasizes timely assessment of heart rate and oxygen need using pulse oximetry to guide ventilation and oxygen administration.

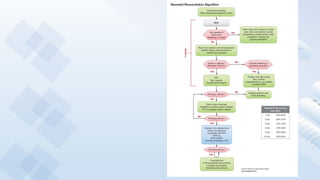

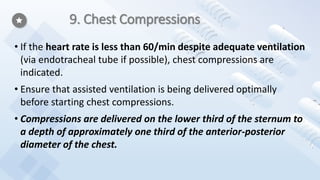

![9. Chest Compressions

• The chest should be allowed to re-expand fully during relaxation [after each

compression], but the rescuer’s thumbs should not leave the chest.

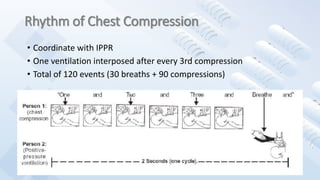

• A 3:1 ratio of compressions to ventilation, with 90 compressions and 30 breaths

to achieve approximately 120 events per minute to maximize ventilation at an

achievable rate is recommended.

• 3:1 compression-to-ventilation ratio is used for neonatal resuscitation where

compromise of gas exchange is nearly always the primary cause of cardiovascular

collapse, but rescuers may consider using higher ratios (eg, 15:2) if the arrest is

believed to be of cardiac origin

• Respirations, heart rate, and oxygenation should be reassessed periodically, and

coordinated chest compressions and ventilations should continue until the

spontaneous heart rate is ≥ 60 per minute.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/newbornresuscitation-200913083905/85/Newborn-Resuscitation-50-320.jpg)

![10.1 Epinephrine

• IV administration of 0.01 to 0.03 mg/kg per dose

is the preferred route [for epinephrine

administration].

• While access is being obtained, administration of a

higher dose (0.05 to 0.1 mg/kg) through the

endotracheal tube may be considered, but the

safety and efficacy of this practice have not been

evaluated.

• Concentration of epinephrine for either route

should be 1:10 000 (0.1 mg/mL).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/newbornresuscitation-200913083905/85/Newborn-Resuscitation-53-320.jpg)