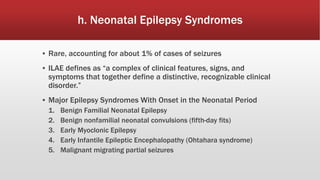

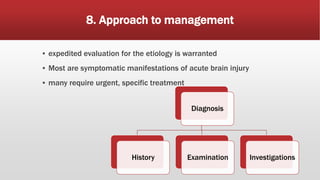

This document provides an overview of neonatal seizures. Key points include:

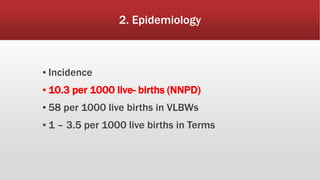

- Neonatal seizures have an incidence of 10.3 per 1000 live births and are more common in preterm infants.

- They are defined as abnormal excessive neuronal activity causing alterations in motor, behavioral or autonomic functions.

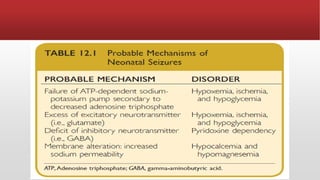

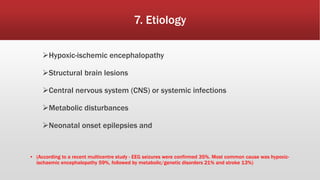

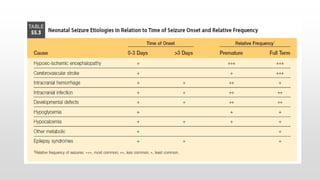

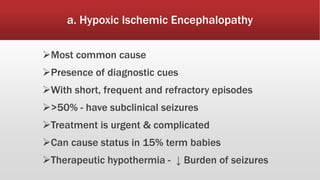

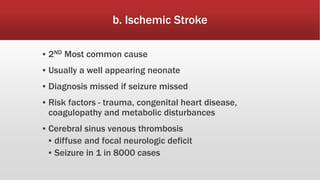

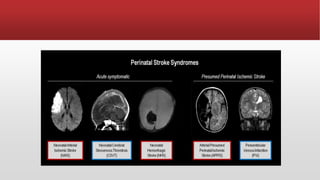

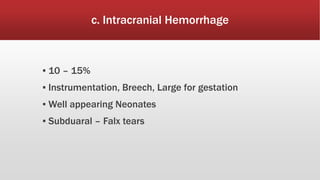

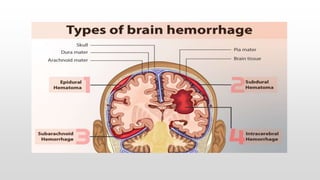

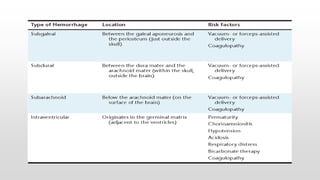

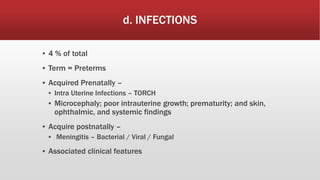

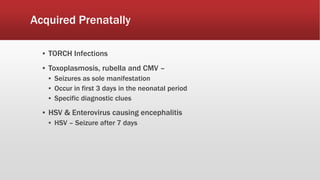

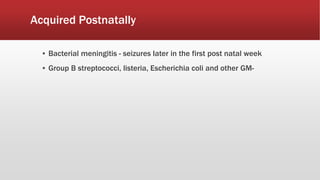

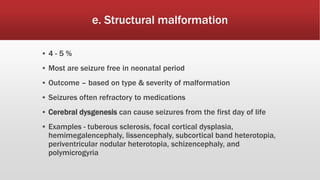

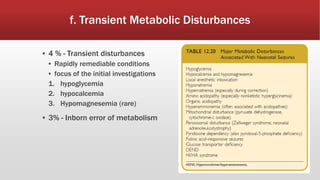

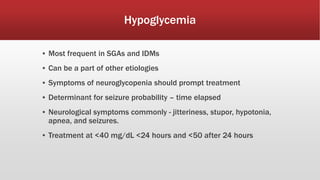

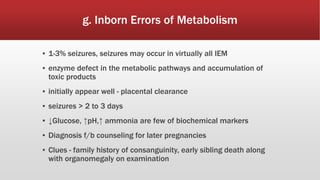

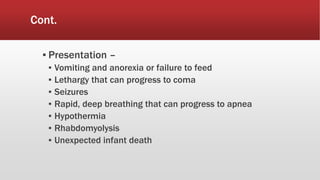

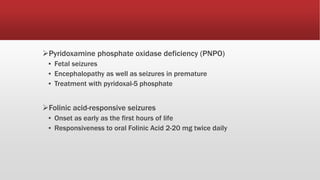

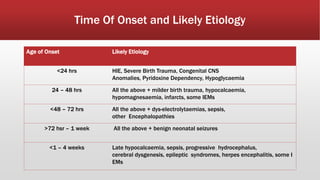

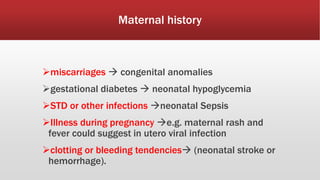

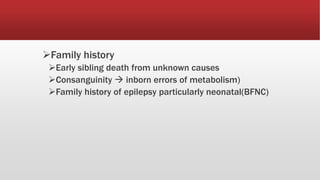

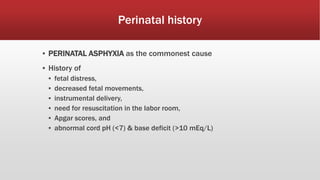

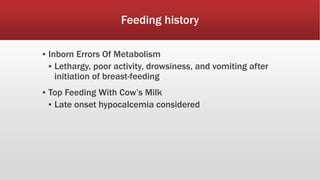

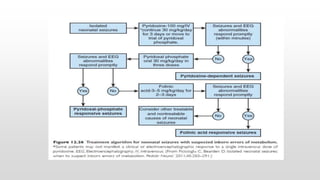

- Common causes include hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, structural brain lesions, infections, and metabolic disturbances.

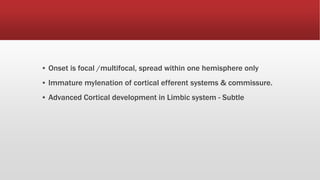

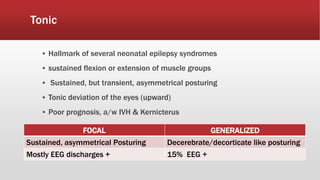

- Seizures are classified based on their clinical presentation and EEG findings as subtle, clonic, tonic, myoclonic or EEG-only.

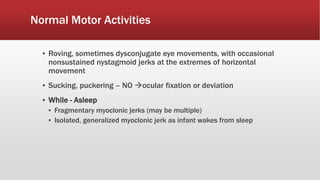

- Differentiating seizures from non-seizure events like apnea or jitteriness is important.

![REFERENCES

1. Cloherty and starks manual of neonatal care 8th edition.

2. Aiims protocols in neonatology

3. Avery’s diseases of the newborn. -- 9th ed. / [Edited by] christine

A. Gleason, sherin U. Devask

4. Fanaroff and martin’s neonatal-perinatal medicine : diseases of

the fetus and infant / [edited by] richard J. Martin, avroy A.

Fanaroff, michele C. Walsh.—10th edition.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/neonatalseizuredrpraman3-210713035852/85/Neonatal-seizure-by-dr-praman-98-320.jpg)