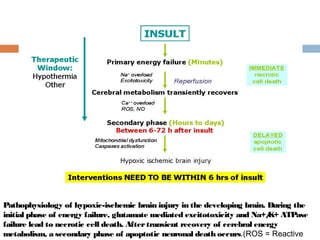

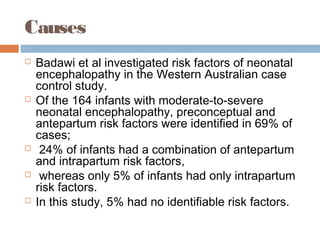

Perinatal asphyxia, or hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE), is a significant cause of neonatal mortality and morbidity, accounting for 23% of all neonatal deaths worldwide. It results from systemic hypoxemia and reduced cerebral blood flow, causing acute brain injury and leading to a range of neurological impairments in affected infants. The condition can arise from events before, during, or after birth, and its diagnosis and categorization rely on a combination of clinical signs and laboratory findings, while the pathophysiology involves complex biochemical processes resulting in neuronal damage.

![at least 2 of the following:

lethargy, stupor, or coma;

abnormal tone or posture;

abnormal reflexes [suck, grasp, Moro, gag,

stretch reflexes];

decreased or absent spontaneous activity;

autonomic dysfunction [including bradycardia,

abnormal pupils, apneas];

and clinical evidence of seizures, moderately or

severely abnormal amplitude (aEEG)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/perinatalasphyxia-150212093319-conversion-gate01/85/Perinatal-asphyxia-81-320.jpg)

![References

Ferriero DM. Neonatal brain injury. NEng lJ Me d. Nov 4 2004;351(19):1985-95. [Medline].

Perlman JM. Brain injury in the term infant. Se m in Pe rinato l. Dec 2004;28(6):415-24. [Medline].

Grow J, Barks JD. Pathogenesis of hypoxic-ischemic cerebral injury in the term infant: current

concepts.Clin Pe rinato l. Dec 2002;29(4):585-602, v. [Medline].

Srinivasakumar P, Zempel J, Wallendorf M, Lawrence R, Inder T, Mathur A. Therapeutic

hypothermia in neonatal hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy: electrographic seizures and

magnetic resonance imaging evidence of injury. JPe diatr. Aug 2013;163(2):465-70. [Medline].

Shankaran S. The postnatal management of the asphyxiated term infant. Clin Pe rinato l. Dec

2002;29(4):675-92. [Medline].

Stola A, Perlman J. Post-resuscitation strategies to avoid ongoing injury following intrapartum

hypoxia-ischemia. Se m in Fe talNe o natalMe d. Dec 2008;13(6):424-31. [Medline].

Laptook A, Tyson J, Shankaran S, et al. Elevated temperature after hypoxic-ischemic

encephalopathy: risk factor for adverse outcomes. Pe diatrics . Sep 2008;122(3):491-

9. [Medline]. [Full Text].

[Guideline] American Academy of Pediatrics. Relation between perinatal factors and neurological

outcome. In: Guidelines for Perinatal Care. 3rd ed. Elk Grove Village, Ill: American Academy of

Pediatrics; 1992:221-234.

[Guideline] Committee on fetus and newborn, American Academy of Pediatrics and Committee

on obstetric practice, American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Use and abuse of the

APGAR score.Pe diatr. 1996;98:141-142. [Medline].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/perinatalasphyxia-150212093319-conversion-gate01/85/Perinatal-asphyxia-105-320.jpg)

![References

Papile LA, Rudolph AM, Heymann MA. Autoregulation of cerebral blood flow in the preterm fetal lamb.Pe dia tr

Re s. Feb 1985;19(2):159-61. [Medline].

Rosenkrantz TS, Diana D, Munson J. Regulation of cerebral blood flow velocity in nonasphyxiated, very low birth

weight infants with hyaline membrane disease. JPe rinato l. 1988;8(4):303-8. [Medline].

Pacher P, Beckman JS, Liaudet L. Nitric oxide and peroxynitrite in health and disease. Physio lRe v. Jan

2007;87(1):315-424. [Medline].

Roth SC, Baudin J, Cady E, Johal K, Townsend JP, Wyatt JS. Relation of deranged neonatal cerebral oxidative

metabolism with neurodevelopmental outcome and head circumference at 4 years. De v Me d Child Ne uro l. Nov

1997;39(11):718-25. [Medline].

Berger R, Garnier Y. Pathophysiology of perinatal brain damage. Brain Re s Brain Re s Re v. Aug 1999;30(2):107-

34. [Medline].

Rivkin MJ. Hypoxic-ischemic brain injury in the term newborn. Neuropathology, clinical aspects, and

neuroimaging. Clin Pe rinato l. Sep 1997;24(3):607-25. [Medline].

Vannucci RC. Mechanisms of perinatal hypoxic-ischemic brain damage. Se m in Pe rinato l. Oct 1993;17(5):330-

7. [Medline].

Vannucci RC, Yager JY, Vannucci SJ. Cerebral glucose and energy utilization during the evolution of hypoxic-

ischemic brain damage in the immature rat. JCe re b Blo o d Flo w Me tab. Mar 1994;14(2):279-88.[Medline].

de Haan HH, Hasaart TH. Neuronal death after perinatal asphyxia. Eur JO bste t Gyne co lRe pro d Bio l. Aug

1995;61(2):123-7. [Medline].

McLean C, Ferriero D. Mechanisms of hypoxic-ischemic injury in the term infant. Se m in Pe rinato l. Dec

2004;28(6):425-32. [Medline].

Bryce J, Boschi-Pinto C, Shibuya K, Black RE. WHO estimates of the causes of death in children. Lance t. Mar

26-Apr 1 2005;365(9465):1147-](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/perinatalasphyxia-150212093319-conversion-gate01/85/Perinatal-asphyxia-106-320.jpg)