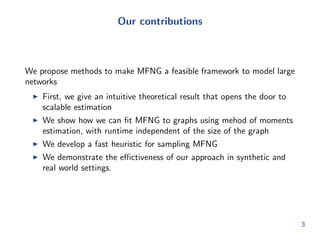

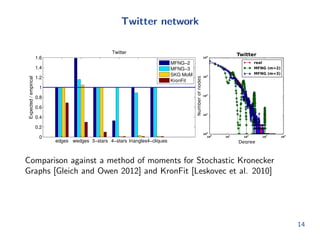

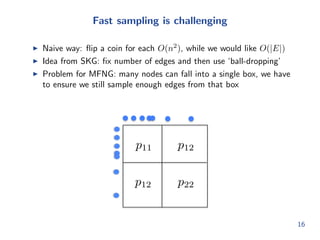

The document presents methods for modeling large networks using multifractal network generators (MFNG), focusing on scalability and estimation. It outlines a theoretical framework that allows for efficient graph generation and parameter fitting through method of moments estimation, demonstrating effectiveness with empirical data from synthetic and real-world networks. The authors also discuss challenges and solutions for fast sampling and estimating network structures.

![Setting

We want a simple, scalable method to model networks and generate

random (undirected) graphs

I Looking for graph generators that can mimic real world graph

structure

{ Power law degree distribution,

{ High clustering coecient, etc.

I Many models have been proposed, starting with Erdos-Renyi graphs

I Relatively recent models: SKG [Leskovec et al. 2010], BTER

[Seshadhri et al. 2012], TCL [Pfeier et al. 2012]

I In 2011 Palla et al. introduce multifractal network generators,

`generalizing' SKG

2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/multifractal-kdd-2014-140906183143-phpapp02/85/Learning-multifractal-structure-in-large-networks-KDD-2014-2-320.jpg)

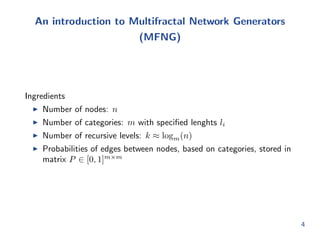

![ed lenghts li

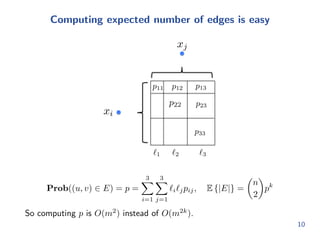

I Number of recursive levels: k logm(n)

I Probabilities of edges between nodes, based on categories, stored in

matrix P 2 [0; 1]mm

4](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/multifractal-kdd-2014-140906183143-phpapp02/85/Learning-multifractal-structure-in-large-networks-KDD-2014-7-320.jpg)

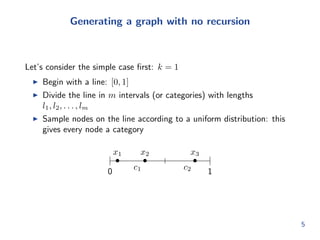

![rst: k = 1

I Begin with a line: [0; 1]

I Divide the line in m intervals (or categories) with lengths

l1; l2; : : : ; lm

I Sample nodes on the line according to a uniform distribution: this

gives every node a category

x2

x3

c1 c2

x1

0 1

5](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/multifractal-kdd-2014-140906183143-phpapp02/85/Learning-multifractal-structure-in-large-networks-KDD-2014-9-320.jpg)

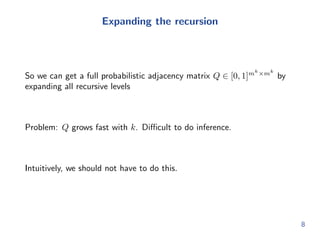

![Expanding the recursion

So we can get a full probabilistic adjacency matrix Q 2 [0; 1]mkmk

by

expanding all recursive levels

Problem: Q grows fast with k. Dicult to do inference.

Intuitively, we should not have to do this.

8](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/multifractal-kdd-2014-140906183143-phpapp02/85/Learning-multifractal-structure-in-large-networks-KDD-2014-15-320.jpg)

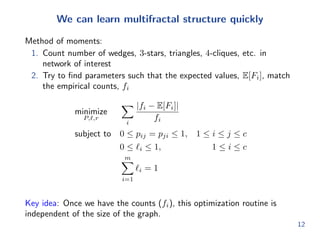

![nd parameters such that the expected values, E[Fi], match

the empirical counts, fi

minimize

P;`;r

X

i

jfi E[Fi]j

fi

subject to 0 pij = pji 1; 1 i j c

0 `i 1; 1 i c

Xm

i=1

`i = 1

Key idea: Once we have the counts (fi), this optimization routine is

independent of the size of the graph.

12](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/multifractal-kdd-2014-140906183143-phpapp02/85/Learning-multifractal-structure-in-large-networks-KDD-2014-20-320.jpg)