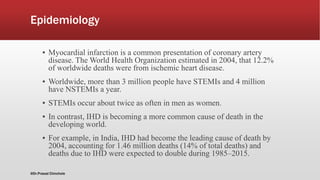

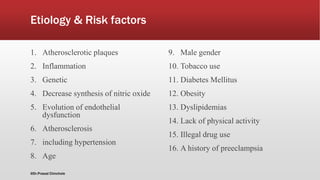

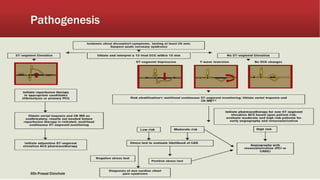

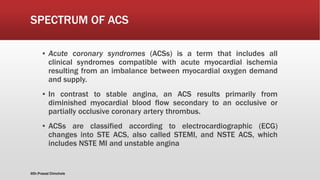

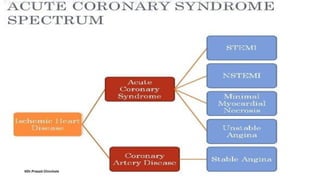

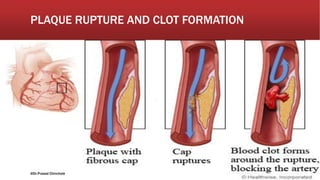

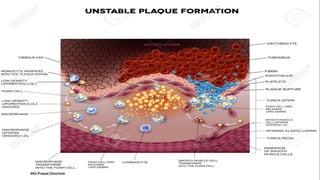

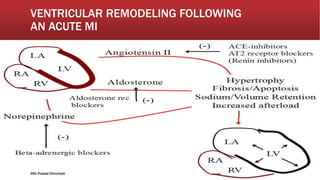

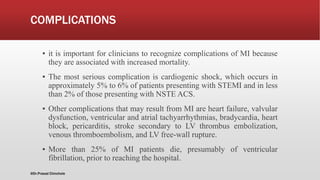

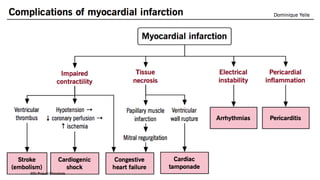

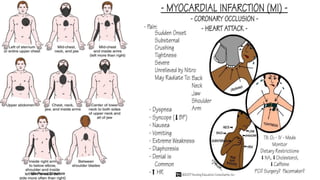

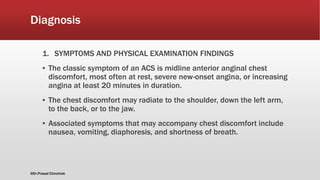

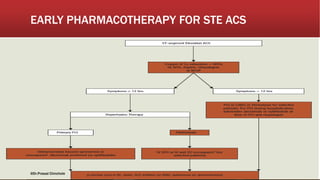

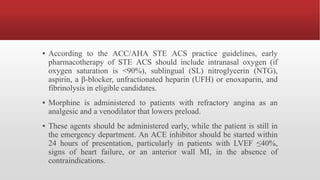

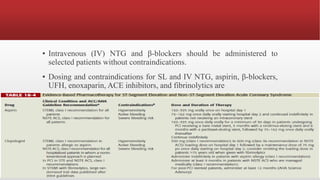

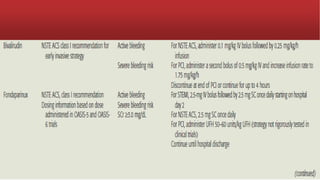

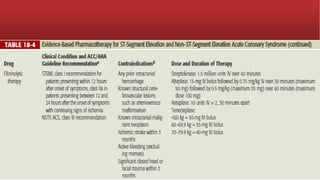

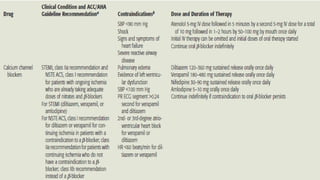

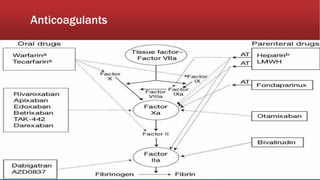

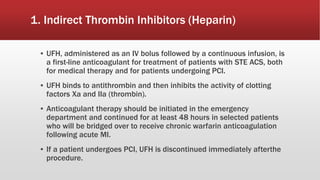

The document provides an extensive overview of myocardial infarction (MI) and acute coronary syndromes, detailing their definitions, causes, symptoms, epidemiology, risk factors, diagnosis, and management strategies. MI, commonly known as a heart attack, results from reduced blood flow to the heart, often triggered by plaque rupture in the coronary arteries, and is characterized by various symptoms including chest pain and shortness of breath. The document emphasizes the importance of early diagnosis and treatment to prevent complications such as heart failure, with management options comprising both pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions.

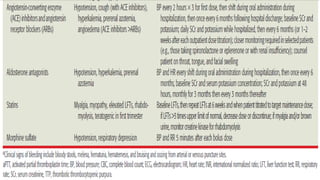

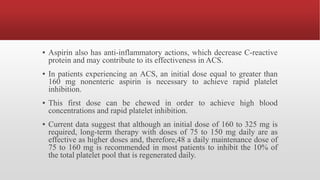

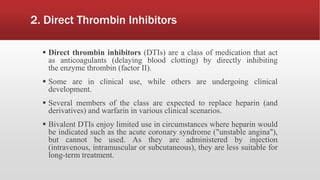

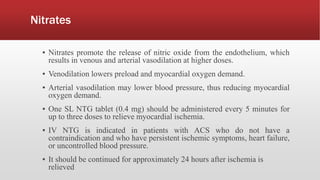

![▪ In general, early pharmacotherapy for NSTE ACS is similar to that for

STE ACS with three exceptions:

1. Fibrinolytic therapy is not administered.

2. GP IIb/IIIa receptor blockers are administered to high-risk patients.

3. There are no standard quality performance measures for patients with

NSTE ACS with unstable angina (not diagnosed with MI).

▪ According to the ACC/AHA NSTE ACS practice guidelines, early

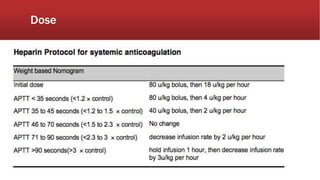

pharmacotherapy for NSTE ACS should include intranasal oxygen (if

oxygen saturation is <90%), SL NTG, aspirin, an oral β- blocker (IV β-

blocker optional), and an anticoagulant (UFH, LMWH [enoxaparin],

fondaparinux, or bivalirudin).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mi-170830053504/85/Mi-91-320.jpg)