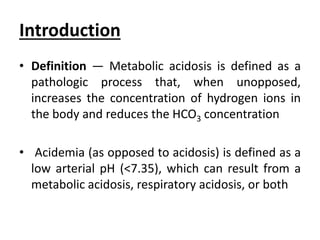

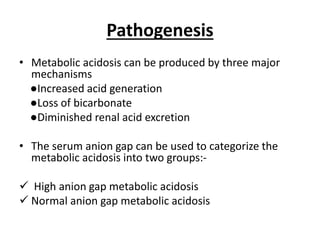

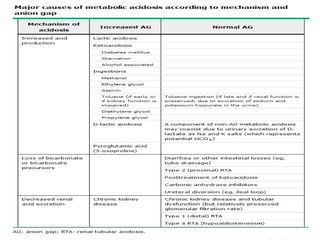

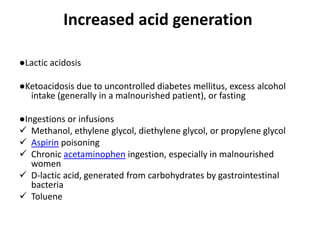

This document provides an overview of metabolic acidosis and alkalosis. It defines metabolic acidosis and acidemia, and describes the three main mechanisms that can produce metabolic acidosis: increased acid generation, loss of bicarbonate, and diminished renal acid excretion. Specific causes of metabolic acidosis like lactic acidosis and ketoacidosis are discussed. The document also covers metabolic alkalosis, describing mechanisms like intracellular shifts of hydrogen ions and gastrointestinal or renal losses of hydrogen ions. Diagnosis and treatment of both conditions in discussed.

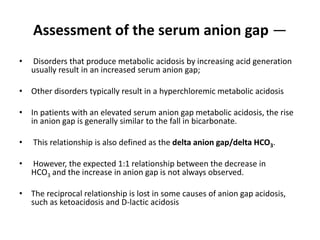

![• The expected "normal" value for the anion gap must be adjusted

downward in patients with hypoalbuminemia. The serum anion gap

falls by 2.3 to 2.5 mEq/L for every 1 g/dL (10 g/L) reduction in the

serum albumin concentration.

• Corrected serum anion gap = (Serum anion gap measured) +

(2.5 x [4.5 - Observed serum albumin])

• In addition to hypoalbuminemia, marked hyperkalemia may affect

the interpretation of the anion gap. Potassium is an "unmeasured"

cation using the equation that does not include the serum K.

• Thus, a serum K of 6 mEq/L will reduce the anion gap by 2 mEq/L.

Hypercalcemia and/or hypermagnesemia will similarly reduce the

anion gap.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/metabolicacidosis-200827155016/85/Metabolic-acidosis-16-320.jpg)

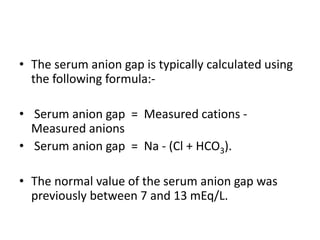

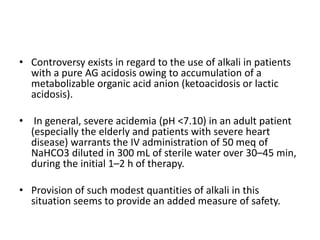

![Treatment

• Treatment of metabolic acidosis with alkali should be

reserved for severe acidemia except when the patient has

no “potential HCO3 −” in plasma.

The potential [HCO3 −] can be estimated from the increment

(Δ) in the AG (ΔAG = patient’s AG – 10), only if the acid

anion that has accumulated in plasma is metabolizable

(i.e., β-hydroxybutyrate, acetoacetate, and lactate).

Conversely nonmetabolizable anions that may accumulate in

advanced stage CKD or after toxin ingestion are not

metabolizable and do not represent “potential” HCO3−](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/metabolicacidosis-200827155016/85/Metabolic-acidosis-22-320.jpg)

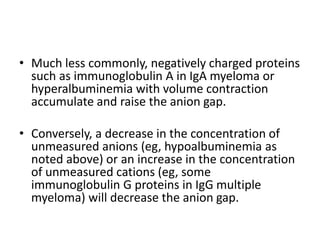

![• With acute CKD improvement in kidney function to

replenish the [HCO3 −] deficit is a slow and often

unpredictable process.

• Consequently, patients with a normal AG acidosis

(hyperchloremic acidosis) or an AG attributable to a

nonmetabolizable anion due to advanced kidney failure

should receive alkali therapy, either PO (NaHCO3 or Shohl’s

solution) or IV (NaHCO3), in an amount necessary to slowly

increase the plasma [HCO3 −] to a target value of 22

mmol/L.

• Nevertheless, overcorrection should be avoided.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/metabolicacidosis-200827155016/85/Metabolic-acidosis-23-320.jpg)

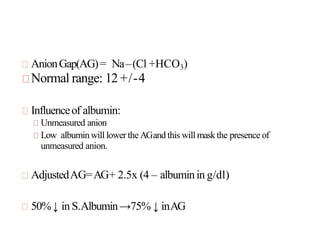

![• Administration of alkali requires careful monitoring of

plasma electrolytes, especially the plasma [K+], during the

course of therapy.

• A reasonable initial goal is to increase the [HCO3 −] to 10–

12 mmol/L and the pH to ∼7.20, but clearly not to increase

these values to normal.

• Estimation of the “bicarbonate deficit” by calculation of the

volume of distribution of bicarbonate is often taught but is

unnecessary and may result in administration of excessive

amounts of alkali.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/metabolicacidosis-200827155016/85/Metabolic-acidosis-25-320.jpg)