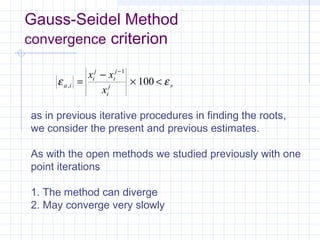

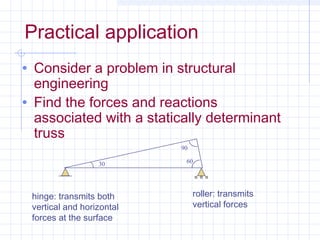

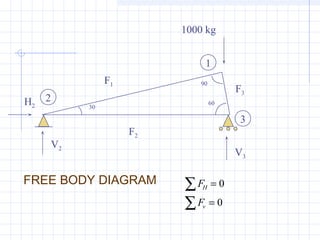

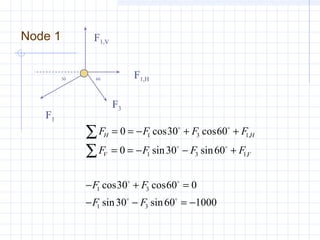

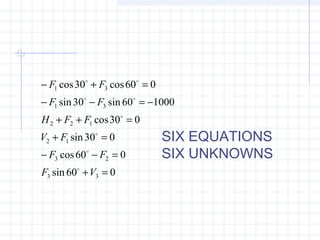

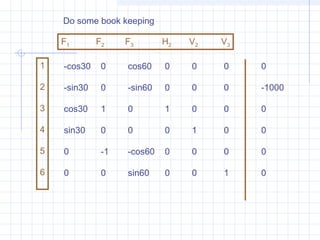

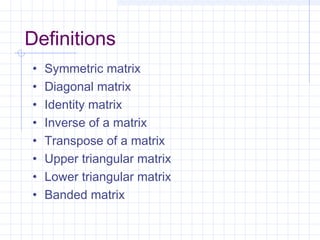

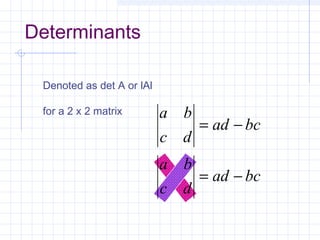

This document provides an overview of matrix methods for solving systems of linear equations. It begins with an example from structural engineering of setting up a system of 6 equations with 6 unknowns to model the forces and reactions in a statically determinant truss. The equations are represented in matrix notation as [A]{x}={c}. The document then reviews key matrix concepts and operations used to solve systems of linear equations, such as matrix addition, multiplication, transposes, inverses, and types of matrices. It aims to help readers understand how to set up and solve systems of linear equations using matrices.

![How to represent a system of linear

equations as a matrix

[A]{x} = {c}

where {x} and {c} are both column vectors](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/matrix-131010034223-phpapp01/85/Matrix-6-320.jpg)

![[ ]

−

−

=

=

−=++

=++

−=++

44.0

67.0

01.0

5.03.01.0

9.115.0

152.03.0

}{}{

44.05.03.01.0

67.09.15.0

01.052.03.0

3

2

1

321

321

321

x

x

x

CXA

xxx

xxx

xxx

How to represent a system of linear

equations as a matrix](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/matrix-131010034223-phpapp01/85/Matrix-7-320.jpg)

![This is the basis for your matrices and the equation

[A]{x}={c}

−

− −

− −

=

−

0866 0 05 0 0 0

05 0 0866 0 0 0

0 866 1 0 1 0 0

05 0 0 0 1 0

0 1 05 0 0 0

0 0 0866 0 0 1

0

1000

0

0

0

0

1

2

3

2

2

3

. .

. .

.

.

.

.

F

F

F

H

V

V](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/matrix-131010034223-phpapp01/85/Matrix-15-320.jpg)

![Mathematical Background

Matrix Notation

• a horizontal set of elements is called a row

• a vertical set is called a column

• first subscript refers to the row number

• second subscript refers to column number

[ ]A

a a a a

a a a a

a a a a

n

n

m m m mn

=

11 12 13 1

21 22 23 2

1 2 3

...

...

. . . .

...](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/matrix-131010034223-phpapp01/85/Matrix-18-320.jpg)

![[ ]

=

mnmmm

n

n

aaaa

aaaa

aaaa

A

...

....

...

...

321

2232221

1131211

This matrix has m rows an n column.

It has the dimensions m by n (m x n)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/matrix-131010034223-phpapp01/85/Matrix-19-320.jpg)

![[ ]

=

mnmmm

n

n

aaaa

aaaa

aaaa

A

...

....

...

...

321

2232221

1131211

This matrix has m rows and n column.

It has the dimensions m by n (m x n)

note

subscript](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/matrix-131010034223-phpapp01/85/Matrix-20-320.jpg)

![[ ]A

a a a a

a a a a

a a a a

n

n

m m m mn

=

11 12 13 1

21 22 23 2

1 2 3

...

...

. . . .

...

row 2

column 3

Note the consistent

scheme with subscripts

denoting row,column](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/matrix-131010034223-phpapp01/85/Matrix-21-320.jpg)

![Row vector: m=1

Column vector: n=1 Square matrix: m = n

[ ] [ ]B b b bn= 1 2 .......

[ ]C

c

c

cm

=

1

2

.

.

[ ]A

a a a

a a a

a a a

=

11 12 13

21 22 23

31 32 33

Types of Matrices](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/matrix-131010034223-phpapp01/85/Matrix-22-320.jpg)

![Symmetric Matrix

aij = aji for all i’s and j’s

[ ]A =

5 1 2

1 3 7

2 7 8

Does a23 = a32 ?

Yes. Check the other elements

on your own.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/matrix-131010034223-phpapp01/85/Matrix-24-320.jpg)

![Diagonal Matrix

A square matrix where all elements

off the main diagonal are zero

[ ]A

a

a

a

a

=

11

22

33

44

0 0 0

0 0 0

0 0 0

0 0 0](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/matrix-131010034223-phpapp01/85/Matrix-25-320.jpg)

![Identity Matrix

A diagonal matrix where all elements

on the main diagonal are equal to 1

[ ]A =

1 0 0 0

0 1 0 0

0 0 1 0

0 0 0 1

The symbol [I] is used to denote the identify matrix.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/matrix-131010034223-phpapp01/85/Matrix-26-320.jpg)

![Inverse of [A]

[ ][ ] [ ] [ ] [ ]IAAAA ==

−− 11](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/matrix-131010034223-phpapp01/85/Matrix-27-320.jpg)

![Transpose of [A]

[ ]A

a a a

a a a

a a a

t

m

m

n n mn

=

11 21 1

12 22 2

1 2

. . .

. . .

. . . . . .

. . . . . .

. . . . . .

. . .](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/matrix-131010034223-phpapp01/85/Matrix-28-320.jpg)

![Upper Triangle Matrix

Elements below the main diagonal

are zero

[ ]A

a a a

a a

a

=

11 12 13

22 23

33

0

0 0](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/matrix-131010034223-phpapp01/85/Matrix-29-320.jpg)

![Lower Triangular Matrix

All elements above the main

diagonal are zero

[ ]A =

5 0 0

1 3 0

2 7 8](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/matrix-131010034223-phpapp01/85/Matrix-30-320.jpg)

![Banded Matrix

All elements are zero with the

exception of a band centered on the

main diagonal

[ ]A

a a

a a a

a a a

a a

=

11 12

21 22 23

32 33 34

43 44

0 0

0

0

0 0](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/matrix-131010034223-phpapp01/85/Matrix-31-320.jpg)

![Matrix Operating Rules

• Addition/subtraction

• add/subtract corresponding terms

• aij + bij = cij

• Addition/subtraction are commutative

• [A] + [B] = [B] + [A]

• Addition/subtraction are associative

• [A] + ([B]+[C]) = ([A] +[B]) + [C]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/matrix-131010034223-phpapp01/85/Matrix-32-320.jpg)

![Matrix Operating Rules

• Multiplication of a matrix [A] by a scalar

g is obtained by multiplying every

element of [A] by g

[ ] [ ]B g A

ga ga ga

ga ga ga

ga ga ga

n

n

m m mn

= =

11 12 1

21 22 2

1 2

. . .

. . .

. . . . . .

. . . . . .

. . . . . .

. . .](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/matrix-131010034223-phpapp01/85/Matrix-33-320.jpg)

![Matrix Operating Rules

• The product of two matrices is represented as

[C] = [A][B]

• n = column dimensions of [A]

• n = row dimensions of [B]

c a bij ik kj

k

N

=

=

∑1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/matrix-131010034223-phpapp01/85/Matrix-34-320.jpg)

![[A] m x n [B] n x k = [C] m x k

interior dimensions

must be equal

exterior dimensions conform to dimension of resulting matrix

Simple way to check whether

matrix multiplication is possible](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/matrix-131010034223-phpapp01/85/Matrix-35-320.jpg)

![Recall the equation presented for

matrix multiplication

• The product of two matrices is represented as

[C] = [A][B]

• n = column dimensions of [A]

• n = row dimensions of [B]

c a bij ik kj

k

N

=

=

∑1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/matrix-131010034223-phpapp01/85/Matrix-36-320.jpg)

![Example

Determine [C] given [A][B] = [C]

[ ]

[ ]

−

−

=

−

−

=

203

123

142

320

241

231

B

A](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/matrix-131010034223-phpapp01/85/Matrix-37-320.jpg)

![Matrix multiplication

• If the dimensions are suitable, matrix

multiplication is associative

• ([A][B])[C] = [A]([B][C])

• If the dimensions are suitable, matrix

multiplication is distributive

• ([A] + [B])[C] = [A][C] + [B][C]

• Multiplication is generally not

commutative

• [A][B] is not equal to [B][A]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/matrix-131010034223-phpapp01/85/Matrix-38-320.jpg)

![Matrix Methods

• Cramer’s Rule

• Gauss elimination

• Matrix inversion

• Gauss Seidel/Jacobi

[ ]A

a a a

a a a

a a a

=

11 12 13

21 22 23

31 32 33](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/matrix-131010034223-phpapp01/85/Matrix-44-320.jpg)

![Another Check

• Scale the matrix of coefficients, [A], so that the

largest element in each row is 1. If there are

elements of [A]-1

that are several orders of magnitude

greater than one, it is likely that the system is ill-

conditioned.

• Multiply the inverse by the original coefficient matrix.

If the results are not close to the identity matrix, the

system is ill-conditioned.

• Invert the inverted matrix. If it is not close to the

original coefficient matrix, the system is ill-

conditioned.

We will consider how to obtain an inverted matrix later.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/matrix-131010034223-phpapp01/85/Matrix-57-320.jpg)

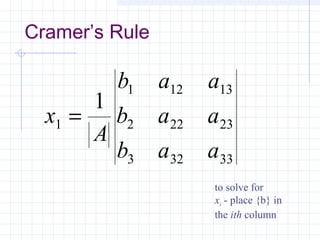

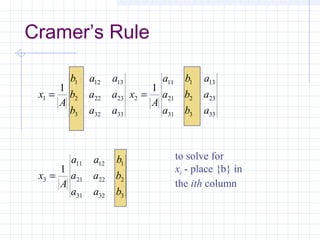

![Cramer’s Rule

• Not efficient for solving large numbers

of linear equations

• Useful for explaining some inherent

problems associated with solving linear

equations.

[ ]{ } { }bxA

b

b

b

x

x

x

aaa

aaa

aaa

=

=

3

2

1

3

2

1

333231

232221

131211](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/matrix-131010034223-phpapp01/85/Matrix-58-320.jpg)

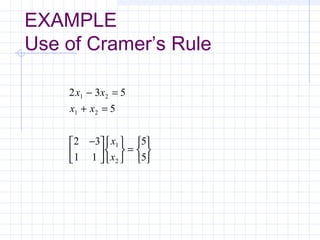

![( )( ) ( )( )

( )( ) ( )( )[ ]

( )( ) ( )( )[ ]

2 3

1 1

5

5

2 1 3 1 2 3 5

1

5

5 3

5 1

1

5

5 1 3 5

20

5

4

1

5

2 5

1 5

1

5

2 5 5 1

5

5

1

1

2

1

2

−

=

= − − = + =

=

−

=

− − = =

= =

− = =

x

x

A

x

x

Solution](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/matrix-131010034223-phpapp01/85/Matrix-62-320.jpg)

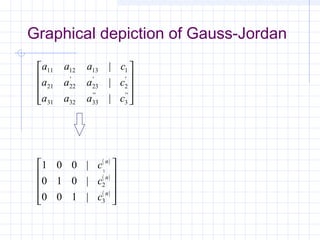

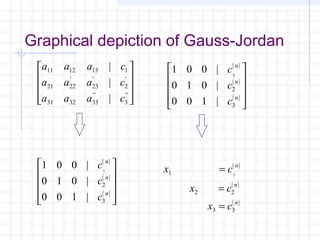

![• All rows are normalized by dividing them by

their pivot elements

• Elimination step results in an identity matrix

rather than an UT matrix

[ ]A

a a a

a a

a

=

11 12 13

22 23

33

0

0 0 [ ]A =

1 0 0 0

0 1 0 0

0 0 1 0

0 0 0 1

Gauss-Jordan](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/matrix-131010034223-phpapp01/85/Matrix-92-320.jpg)

![Matrix Inversion

• [A] [A] -1

= [A]-1

[A] = I

• One application of the inverse is to solve

several systems differing only by {c}

• [A]{x} = {c}

• [A]-1

[A] {x} = [A]-1

{c}

• [I]{x}={x}= [A]-1

{c}

• One quick method to compute the inverse is

to augment [A] with [I] instead of {c}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/matrix-131010034223-phpapp01/85/Matrix-95-320.jpg)

![Graphical Depiction of the Gauss-Jordan

Method with Matrix Inversion

[ ] [ ]

[ ] [ ]

A I

a a a

a a a

a a a

a a a

a a a

a a a

I A

11 12 13

21 22 23

31 32 33

11

1

12

1

13

1

21

1

22

1

23

1

31

1

32

1

33

1

1

1 0 0

0 1 0

0 0 1

1 0 0

0 1 0

0 0 1

− − −

− − −

− − −

−

Note: the superscript

“-1” denotes that

the original values

have been converted

to the matrix inverse,

not 1/aij](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/matrix-131010034223-phpapp01/85/Matrix-96-320.jpg)

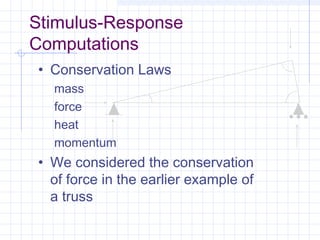

![• [A]{x}={c}

• [interactions]{response}={stimuli}

• Superposition

• if a system subject to several different stimuli, the

response can be computed individually and the

results summed to obtain a total response

• Proportionality

• multiplying the stimuli by a quantity results in the

response to those stimuli being multiplied by the

same quantity

• These concepts are inherent in the scaling of terms

during the inversion of the matrix

Stimulus-Response Computations](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/matrix-131010034223-phpapp01/85/Matrix-99-320.jpg)