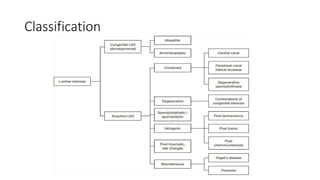

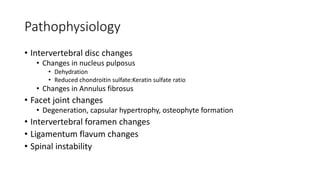

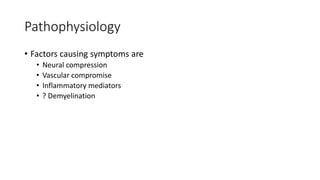

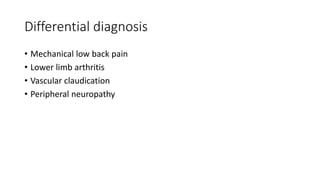

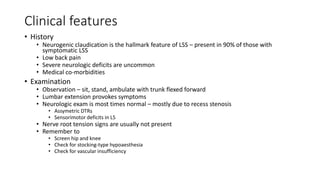

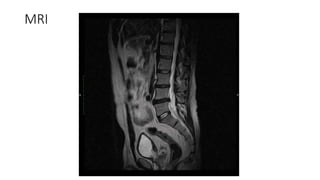

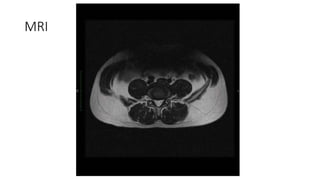

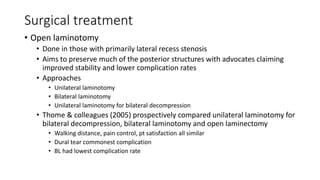

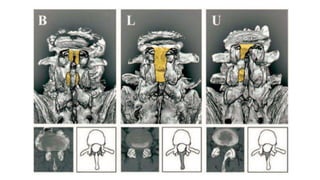

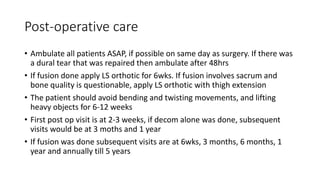

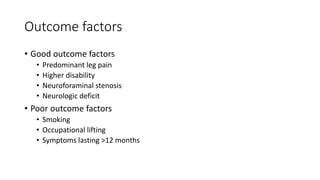

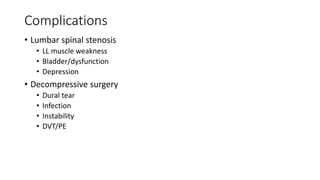

Lumbar spinal stenosis is a common condition among older adults causing lower back and leg pain. It results from the narrowing of the spinal canal which compresses the nerves and blood vessels. Key features include neurogenic claudication pain that worsens with standing or walking and is relieved by bending forward. Treatment involves non-operative options like medication, injections and physical therapy initially. For those with more severe symptoms, open decompressive laminectomy is currently the gold standard surgical treatment, though minimally invasive techniques are gaining popularity due to lower complication rates. Proper patient selection and postoperative rehabilitation are important for achieving good long-term outcomes.